Scientology Is Not a Religion

Germany treats L. Ron Hubbard’s movement as a cult and a threat to democracy. The U.S. should follow its example.

“In the 1930s it was the Jews. Today it is the Scientologists.” So read a full-page open letter, published in the International Herald Tribune on Jan. 9, 1997, to then-German Chancellor Helmut Kohl. Signed by 34 prominent figures in the entertainment industry—none of them Scientologists and many of them Jews—the letter went on to accuse the German government of “repeating the deplorable tactics” of Nazi Germany against the self-proclaimed religion started in 1952 by science-fiction author L. Ron Hubbard.

This initiative, endorsed by the likes of Goldie Hawn, Larry King, Dustin Hoffman, and Oliver Stone, was orchestrated not by the Church of Scientology but by Bertram Fields, lawyer to the sect’s most famous member, Tom Cruise. Yet it conformed to the Church’s campaign, started several years earlier, to brand modern Germany as akin to the Third Reich. A Scientology-sponsored ad that ran on Sept. 29, 1994, in the Washington Post, for instance, declared that 50 years after the Holocaust “neo-Nazi extremism is on the march in a reunited Germany.” In 1996, a Scientology advertisement in the New York Times stated, “You may wonder why German officials discriminate against Scientologists. There is no legitimate reason but then there was none that justified the persecution of the Jewish people either.”

By likening the German government’s treatment of Scientologists to Nazi barbarism, the Church of Scientology didn’t just draw a vulgar comparison: It turned the country’s official anti-Scientology posture on its head. Since the Church established itself here in 1970, the German government has waged a long-running legal and political battle against it. The government makes its logic plain: Because of its history of Nazism, Germany believes it has an obligation to root out extremists, and not just those of a political flavor. In the eyes of most Germans, Scientology is nothing more than a cult with authoritarian designs on the country’s hard-won pluralistic democracy.

While several governments around the world have set up commissions to study Scientology in order to determine whether it qualifies as a religion, Germany broke new ground when, in 1992, the city of Hamburg set up a “Scientology Task Force” to monitor the group, assist members who have left the Church and are thus cut off from their families, and discourage citizens from joining it in the first place. (That office, which maintained a vast and extensive archive of official Scientology documents, many of them classified by the Church, was closed due to government budget cuts in 2010.)

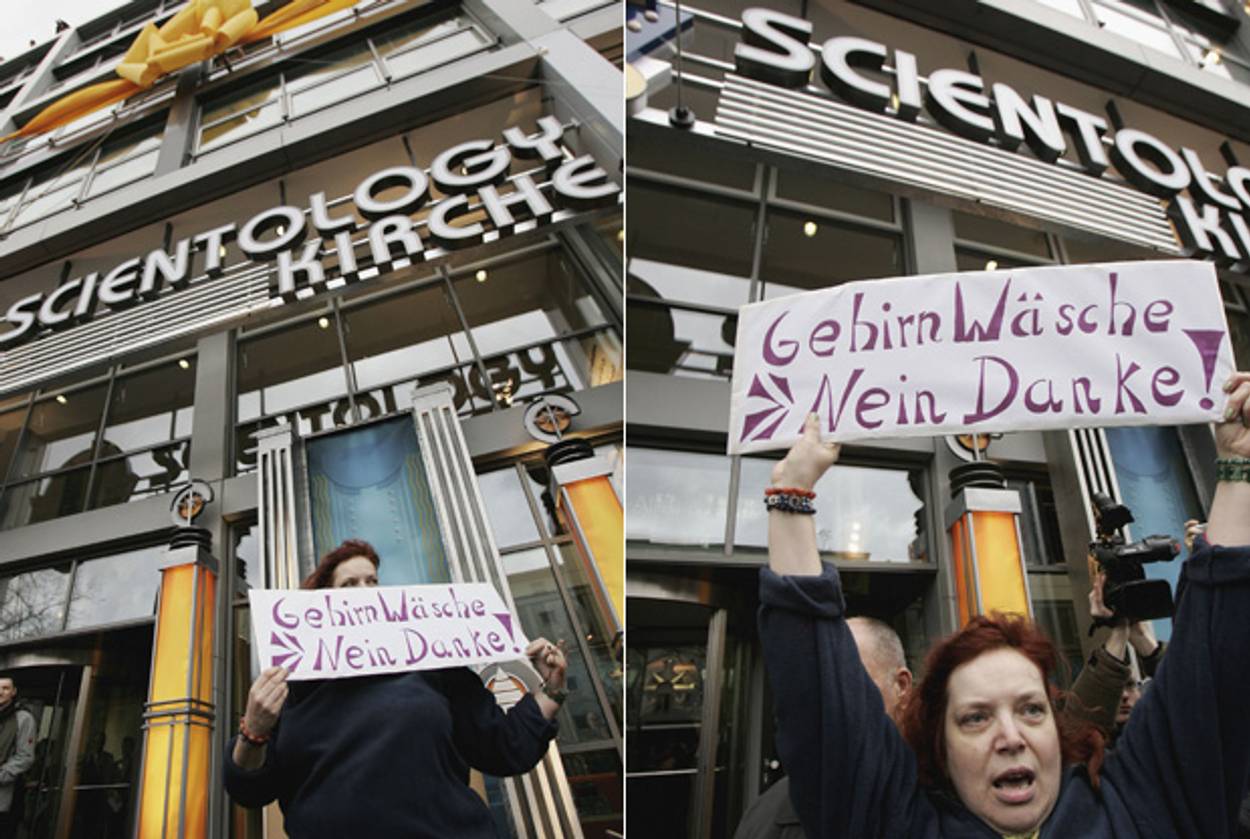

The former head of the Task Force, Ursula Caberta, has labeled Cruise “an enemy of [the German] constitution” and has not so subtly likened the Church to the Third Reich, calling it a “totalitarian organization that seeks to control everybody else, a dictatorship.” Hers is a view that an overwhelming number of Germans seem to share: A 2007 poll found that 74 percent favor banning Scientology. The German equivalent of the FBI, the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (the Bundesamt für Verfassungshutz, or BfV), has been monitoring Scientology since 1997. On the BfV’s homepage, Scientology is listed alongside “Right-wing extremism,” “Islamism,” and “Espionage” as one of its focus areas. (The Hamburg government has even printed pamphlets warning about the dangers of Scientology in Turkish for the country’s sizable Turkish minority.)

Contrast this response to the attitude toward Scientology in the United States, where the Church, though largely seen as a celebrity curiosity, is a tax-exempt, legally recognized religious faith. When Katie Holmes filed for divorce from Tom Cruise two weeks ago, dozens of photographers were dispatched to stake out her exclusive Chelsea apartment building; lawyers took to the airwaves predicting the details of their settlement; and tabloids asked what would happen to Suri, the couple’s 6-year-old daughter. Hovering only in the background has been the Church of Scientology, whose role in the breakup remains as opaque as the SUV-driving stalkers shadowing Holmes in Manhattan.

Meanwhile, in Germany, it is Scientology that has dominated the headlines. “Life in the Tom-Cruise-Cult: A Berlin mother and her son report how they fell into the clutches of the dangerous organization,” shouted a recent front page of B.Z., a popular tabloid in the country’s capital. The German press has portrayed the Church, uniformly, as an evil sect that threatens not only individual Germans but the very basis of the country’s cherished postwar democracy. “The ideology of the organization is completely directly against our liberal-democratic constitutional order,” Caberta, the former head of Hamburg’s Scientology Task Force, told the newspaper. “Members are oppressed, exploited, and psychologically broken.”

On the surface, the German reaction might seem overwrought and apocalyptic. The same BfV report that labels Scientology anti-democratic, for instance, estimated that the group has only about 4,000 to 5,000 members in Germany—far fewer than the 30,000 the Church claims. And a handful of sober German critics allege that their country’s attitude to Scientology resembles a societal panic akin to the McCarthyism of the 1950s. (German commentator Joseph Joffe wrote at the height of the Scientology controversy in 1997 that no Scientologist “has ever been seen training in Germany’s dark forests with an AK-47 in hand.”)

True enough. Yet while Scientology may not represent a clear and present danger to the Federal Republic, its ideology is an authoritarian one, as the writings of its founder and its behavior toward critics and members attest. What might at first appear to be an overreaction—a symptom, perhaps, of the Germans’ tendency to take things too seriously, or of their longing for social ordnung—is an approach the United States should seek to emulate.

***

The broad contours of Scientology’s inception are well-known: In 1950, the pulp sci-fi writer L. Ron Hubbard published a self-help book called Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health, which humbly claimed itself to be “a milestone for Man comparable to his discovery of fire and superior to his inventions of the wheel and the arch.” The book, described by the American Psychological Association as “as hodge-podge of accepted therapeutic techniques with new names,” was filled with astounding claims, like Hubbard’s discovery of something he called “the reactive mind” and that the average American woman attempted abortion 20-30 times in her life. Dianetics was a huge success, selling over half a million copies by the end of the year.

In 1952, Hubbard decided to merge his bunk scientific claims with his science fiction and market the mixture as a religion. He called it Scientology, or, “the science of knowing how to know answers.” According to Church defectors, and now infamous thanks to South Park, Scientology’s theology is essentially a discarded Hubbard novel. Human beings are the composition of spirits (“thetans”) cast off from the bodies of space aliens detonated 75 million years ago in volcanoes on the planet Teegeeack (also known as Earth) by a galactic warrior named Xenu. Man’s problems today are attributable to “engrams,” or the mental memory of painful experiences caused by the presence of thetans on our humanly bodies, which one can get rid of only through a process of spiritual “auditing,” a sort of counseling session performed on a low-rent lie-detector machine called an “E-Meter.” Those who join Scientology often end up spending vast sums on auditing and other Church gimmicks, leading detractors to characterize Scientology as a pyramid scheme in which members pay ever-vaster sums of money to ascend the Church’s “Operating Thetan levels.” A typical story involves the grief-stricken, 73-year-old widow who took on a $45,000 mortgage to pay for auditing after Scientologists preyed upon her following the death of her husband.

A 1972 directive from Hubbard titled “Governing policy,” cited by the German government in its position against the Church, clearly characterizes Scientology as a commercial enterprise. “MAKE MONEY. MAKE MONEY. MAKE MORE MONEY. MAKE OTHER PEOPLE PRODUCE SO AS TO MAKE MONEY,” Hubbard wrote. In 1967, the IRS revoked the Church’s tax-exempt status, a decision reasserted by each and every American court to which the Church brought challenges over a subsequent 25-year-period. A 1984 U.S. Tax Court ruling, for instance, found that the Church “made a business out of selling religion” and that Hubbard and his family had diverted millions of dollars to their personal accounts. The Los Angeles Superior Court, meanwhile, deemed Hubbard “a pathological liar” driven by “egotism, greed, avarice, lust for power and vindictiveness and aggressiveness against persons perceived by him to be disloyal or hostile.”

Desperate for legitimacy, in 1973 Scientology launched Operation Snow White—a covert operation aimed at infiltrating governments. Scientology agents broke into IRS headquarters, bugged its offices, and dispatched private investigators to spy on individual agents—all in hopes of blackmailing officials. All this was permitted under Scientology’s “Fair Game” doctrine, which, according to Hubbard, demands that Church critics “be deprived of property or injured by any means by any Scientologist without any discipline of the Scientologist. May be tricked, sued or lied to or destroyed.” The plot was uncovered in 1977, and Hubbard’s wife and 10 other Church officials were sentenced to jail. Hubbard was named an unindicted co-conspirator.

But in 1993, Scientology finally did achieve tax-exempt status from the IRS—a massive victory in the Church’s quest for mainstream acceptance. It did so, according to the New York Times, only “after an extraordinary campaign orchestrated by Scientology against the agency and people who work there” that included the hiring of “private investigators to dig into the private lives of I.R.S. officials and to conduct surveillance operations to uncover potential vulnerabilities.” Scientology even set up a front group, the National Coalition of IRS Whistle-blowers, to battle the agency. As if to emphasize the capriciousness of the IRS’s decision, just a year before the agency’s reversal, a decision by the U.S. Claims Court rejected Scientology’s case for tax-exemption, citing “the commercial character of much of Scientology,” its virtually incomprehensible financial procedures” and its “scripturally based hostility to taxation.”

Now that the U.S. government recognized Scientology as a religious faith, the Church could claim that the policies of foreign governments amount to religious discrimination. Four months after the IRS decision, the U.S. State Department released its 1994 annual human rights report, which included a paragraph critical of the German government’s measures against Scientology—the first of what would become many such complaints.

While Washington ended its official skepticism of Scientology, European governments grew harsher in their actions against the Church. France, Spain, and Italy raided Scientology centers throughout the 1980s. In 1997, a Greek judge ordered a Scientology center in Athens shut down for “medical, social and ethical practices that are dangerous and harmful,” and an Italian judge ordered 29 Scientologists to jail in 1997 for “criminal association.”

But in no country has Scientology captured the public imagination—and served as the hotbed for international controversy—more than in Germany. In the summer of 1996, the youth wing of the Christian Democratic Union (then and now Germany’s ruling conservative party) called for a boycott of Mission Impossible. At around the same time, stories began appearing in the American press airing allegations from German Scientologists that their children were being barred from certain kindergartens. A state-owned bank shut down accounts belonging to members of the Church, and the provincial government in conservative, Catholic Bavaria announced that it would require applicants for public-sector jobs to declare any connections they might have to the Church. By the middle of the decade, what Frank Rich referred to as “the great American religious saga of the 1990’s” erupted on the other side of the Atlantic, with both sides accusing the other of acting like Nazis.

***

Some German government actions against Scientology have been so earnest that it’s easy for skeptics to mock them as overcompensation for the country’s fascist past. In 2009, for instance, Berlin’s Charlottenberg-Wilmersdorf district government erected a giant poster of a stop sign outside the Church’s headquarters to “express its opposition to the activities of the Scientology sect in this district.” But judging by the writings and political sympathies of its founder, the allegation that Scientology is an authoritarian movement cannot be so easily dismissed.

In his 1951 book, the Science of Survival, Hubbard devised a system of “tones” to measure human emotions. “The sudden and abrupt deletion of all individuals occupying the lower bands of the tone scale from the social order would result in an almost instant rise in the cultural tone and would interrupt the dwindling spiral into which any society may have entered,” Hubbard wrote. “It is not necessary to produce a world of clears [the Scientology term for enlightened person] in order to have a reasonable and worthwhile social order; it is only necessary to delete those individuals who range from 2.0 down, either by processing them enough to get their tone level above the 2.0 line or simply quarantining them from the society.” Promulgating less-mangled formulations of this idea is banned in Germany and other European countries.

Hubbard was a supporter of the Greek military junta (calling the regime’s constitution “the most brilliant tradition of Greek democracy”) and South African apartheid (“not a police state”). The forced relocation of blacks to rural townships, Hubbard wrote in a letter to then-Prime Minister Henrik Verwoerd, was “the most impressive and adequate resettlement activity in existence.” Hubbard suggested that his e-meters be used to interrogate anti-apartheid activists.

In 1966—in one of the strangest episodes in a very strange life—Hubbard spent some three months in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, in an attempt to ingratiate himself with the white minority government’s Prime Minister Ian Smith, who had just unilaterally declared Rhodesia’s independence from the United Kingdom. Hubbard, who believed he had been Cecil Rhodes in a past life, strode around the country sporting the same style hat worn by the great imperialist and tried to present Smith with a new constitution he had written for the country. On its website describing the “worldview” of Scientology, the Baden-Württemberg branch of the BfV cites Hubbard’s use of the racist British expression “wog” to describe non-Scientologists, “a term thrown around liberally among Church staff,” according to Janet Reitman, author of the acclaimed new book Inside Scientology. The Church’s claim that psychiatrists were responsible for the Holocaust—an argument it brought to Germany with an outdoor traveling exhibit in the 1990s—is also something that rankles Germans, not to mention German Jews.

Ironically, the German government bases much of the strict policy toward Scientology upon rulings by U.S. courts. One of the three major U.S. legal findings that the German government cites in a long and detailed explanation of its policy is a 1994 California case, which stated that the Church’s activities took place in a “coercive environment.” The German government also cites a 1997 Illinois Supreme Court ruling regarding allegations that the Church’s vindictive and cynical legal strategy against the Cult Awareness Network, whereby it sued the organization—a support group for cult members and their families—into bankruptcy, assumed its name, and then operated it as a Scientology front. “Such a sustained onslaught of litigation can hardly be deemed ‘ordinary,’ if [the Network] can prove that the actions were brought without probable cause and with malice,” the court found.

Though the Church has won successive attempts by the German government, at both the federal and provincial level, to ban it outright, it still exists in nebulous legal territory, permitted to operate but not recognized as a religion or a nonprofit organization. (Germany isn’t stingy in its designation of tax-exempt status; according to the government, some 10,000 groups are tax-exempt, including the Mormon Church and Jehovah’s Witnesses.) The German government cites a history of court rulings claiming that the Church is in fact a commercial enterprise: For instance, a 1995 decision found that the Church is “masquerading as a religion in order to make a profit.” But the government goes further than the courts in arguing that Scientology represents a unique threat to German society. This is a view that cuts across partisan lines as the leading political parties—the Christian Democratic Union, its Bavarian sister Conservative Social Union, the Social Democrats, and the liberal Free Democrats—all ban Scientologists from membership. According to a 2010 report by the BfV, Scientology “rejects the democratic system; its long-term goal is a social order in which it is the sole authority.”

In 2007, Tom Cruise hoped to shoot the film Valkyrie, a docudrama about German officers’ plot to kill Hitler in which the Scientology star played ringleader Col. Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg, in Germany. When German military officials attempted to prevent filming in the building where the plotters were eventually executed, all the hoary old arguments likening contemporary Germany to Nazism came back to the fore. But many Germans saw Cruise’s assuming the role of the German hero as galling. Berthold Graf von Stauffenberg, the colonel’s eldest son and himself a former general in the West German army, voiced widespread German feeling when he said, “The fact that an avowed Scientologist like Cruise is supposed to play the victim of a totalitarian regime is purely sick.” (The German government, in a surprising turn-around, later agreed to let Cruise film inside the Defense Ministry.)

***

Around the world, a handful of politicians have urged their governments to prosecute Scientology as a criminal conspiracy. Three years ago, a Paris court found the Church guilty of fraud and fined it $900,000. That same year, a member of the Australian Senate, Nick Xenophon, delivered a speech in which he described Scientology as “criminal organization that hides behind its so-called religious beliefs.” After calling for an investigation into the Church’s tax-exempt status during a television interview, he began to receive letters from ex-Scientologists across Australia detailing what he described as “a worldwide pattern of abuse and criminality,” including torture, forced confinement, and coerced abortions. (Xenophon’s call for a parliamentary inquiry into the Church was ultimately rejected by the Australian government.) In 2007, following a 10-year investigation, a Belgian prosecutor called for the Church to be labeled a criminal organization and recommended that up to 12 Church officials face charges for the illegal practice of medicine, violation of privacy, and use of illegal contracts. The State Department criticized the move, stating that the United States would “oppose any effort to stigmatize an entire group based solely upon religious beliefs and would be concerned over infringement of any individual’s rights because of religious affiliation.”

But it was not long ago that the U.S. government came close to cracking down on Scientology. In a New Yorker profile last year of Paul Haggis, the Academy Award-winning director of Crash who recently defected from the Church, Lawrence Wright reported that the FBI was investigating Scientology on charges of human trafficking. According to Tony Ortega, the editor of the Village Voice who has long written about the Church, the bureau was preparing to raid Scientology’s California international headquarters—using footage it had shot with drone aircraft—based upon evidence that a defector had given them about “an office-prison made up of two double-wide trailers where fallen officials were kept day and night, sleeping on the floor and being forced to take part in mass confessions.” The probe was ultimately called off for unknown reasons.

But a series of high-level defections over the past several decades demonstrates just how dangerous the Church has become. This month, Tanja Castle, the former executive secretary to Church leader David Miscavige, told the story of how, in 2004, she had to physically flee the Church’s California headquarters, jumping over a razor-wire fence. She had been forced by Church leaders to “disconnect” from her husband, who had been accused of financial misconduct. “We were first discouraged, and then not allowed to communicate with each other, or see each other, or be a married couple,” she told an ABC affiliate in California.

Earlier this year, a former Scientology executive named Debbie Cook told a Texas court that, in the summer of 2007, she had been held in a prison-like compound called “The Hole,” with 100 other Church members. According to the Tampa Bay Times, which covered the case, “They spent their nights in sleeping bags on ant-infested floors, ate a soupy ‘slop’ of reheated leftovers and screamed at each other in confessionals that often turned violent.” Cook further “described a 12-hour ordeal at the California base where she was made to stand in a trash can while fellow executives poured water over her, screamed at her and said she was a lesbian.”

***

For obvious reasons—beginning with the Constitution, and the fact the United States was founded by Europeans fleeing religious persecution—most Americans are loath to do anything that would appear to infringe upon someone else’s religious liberty. Though some of us may find each other’s religious convictions, or religion itself, strange, few believe that it should be the government’s role to tell other people how, if at all, to pray. And so while the consensus in the United States may be that Scientology is a bit nutty, the general attitude, owing to Americans’ dedication to individual liberty, seems to be: live and let live. The problem with Scientology is that it is not content to let other people “let live,” certainly not those who join the Church or criticize it from the outside.

The differences in historical traditions of American individualism and European communalism should not be used to discourage a tougher American approach to dealing with the Church of Scientology. Revoking its ill-gotten tax-exempt status is the obvious first start, followed by an end to criticism of foreign governments, such as Germany’s, for doing precisely what the U.S. government should be doing: investigating Scientology as a harmful enterprise, with the ultimate aim of shutting it down. Congress should establish a commission, as have many other governments, to investigate the Church and its activities and actively warn citizens about its dangers. Such policies should be seen as no different from a public-health measure, like long-existing, widely popular government campaigns to discourage smoking.

Nearly 50 years ago, the Australian state of Victoria launched just such an investigation into Scientology. “There are some features of Scientology which are so ludicrous that there may be a tendency to regard Scientology as silly and its practitioners as harmless cranks,” the Board of Inquiry into Scientology found. But the activities of the Church were no laughing matter. “Scientology is evil; its techniques evil; its practice a serious threat to the community, medically, morally and socially; and its adherents sadly deluded and often mentally ill.” The Church was gradually shut down in several provinces but fought back hard, winning nationwide legal recognition in 1983.

Scientology isn’t just about space aliens and brainwashed actors jumping on couches. The relative handful of high-profile adherents obscures its many everyday victims, people whose lives and families have been destroyed by this cult. It may not be the role of a government in a free society to prevent its citizens from making unwise decisions. But surely it should take reasonable measures to prevent the unscrupulous and deceitful from brainwashing and abusing people. As Katie Holmes can no doubt attest, it’s long past time Americans stopped joking about Scientology and started treating it like the Germans do.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

James Kirchick, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution, is a columnist at Tablet magazine and the author of The End of Europe: Dictators, Demagogues and the Coming Dark Age. He is writing a history of gay Washington, D.C. His Twitter feed is @jkirchick.

James Kirchick is a Tablet columnist and the author of Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington (Henry Holt, 2022). He tweets @jkirchick.