Better a Pharaoh or a Tempest?

They say democracies make good neighbors. For Israel these days, it doesn’t seem so straightforward.

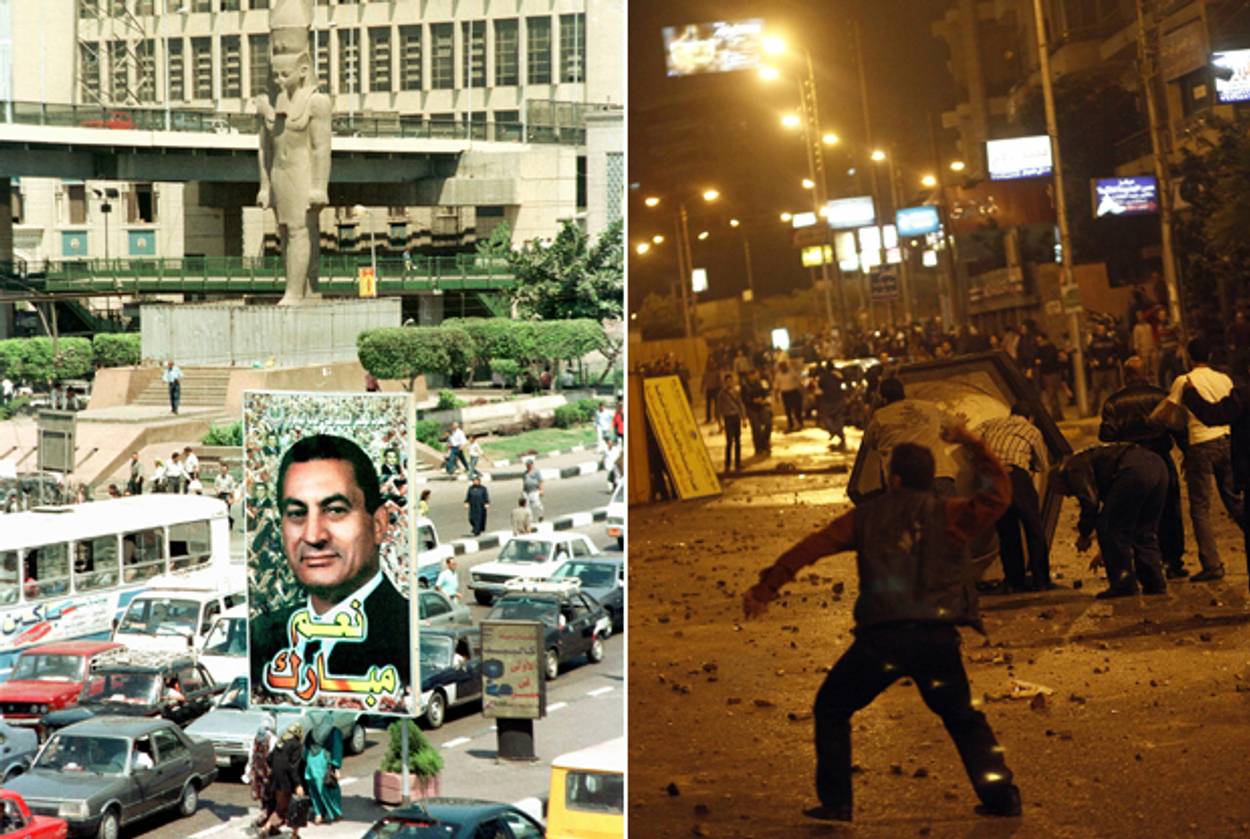

It took Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi to crystallize the enduring tension highlighted by regimes that conduct themselves responsibly abroad while violating people’s liberties at home. Morsi may be the first democratically elected ruler of his country in six decades—he reminded one and all in his statement justifying his broad powers that he had been chosen by “God and the people”—but over the past few weeks he’s borrowed a page from the book of Hosni Mubarak: brokering a cease-fire between Israel and the Hamas rulers of Gaza and then, in a flash, suspending the constitutional life of his country, asserting sweeping powers that put all his decisions beyond judicial review. Morsi had assumed that his writ would be deemed acceptable, but the protesters that had upended Hosni Mubarak’s dictatorship were not ready for a new pharaoh. Popular outrage, and the opposition of some leading political figures in the country, forced Morsi to rescind his extrajudicial claim a mere fortnight later.

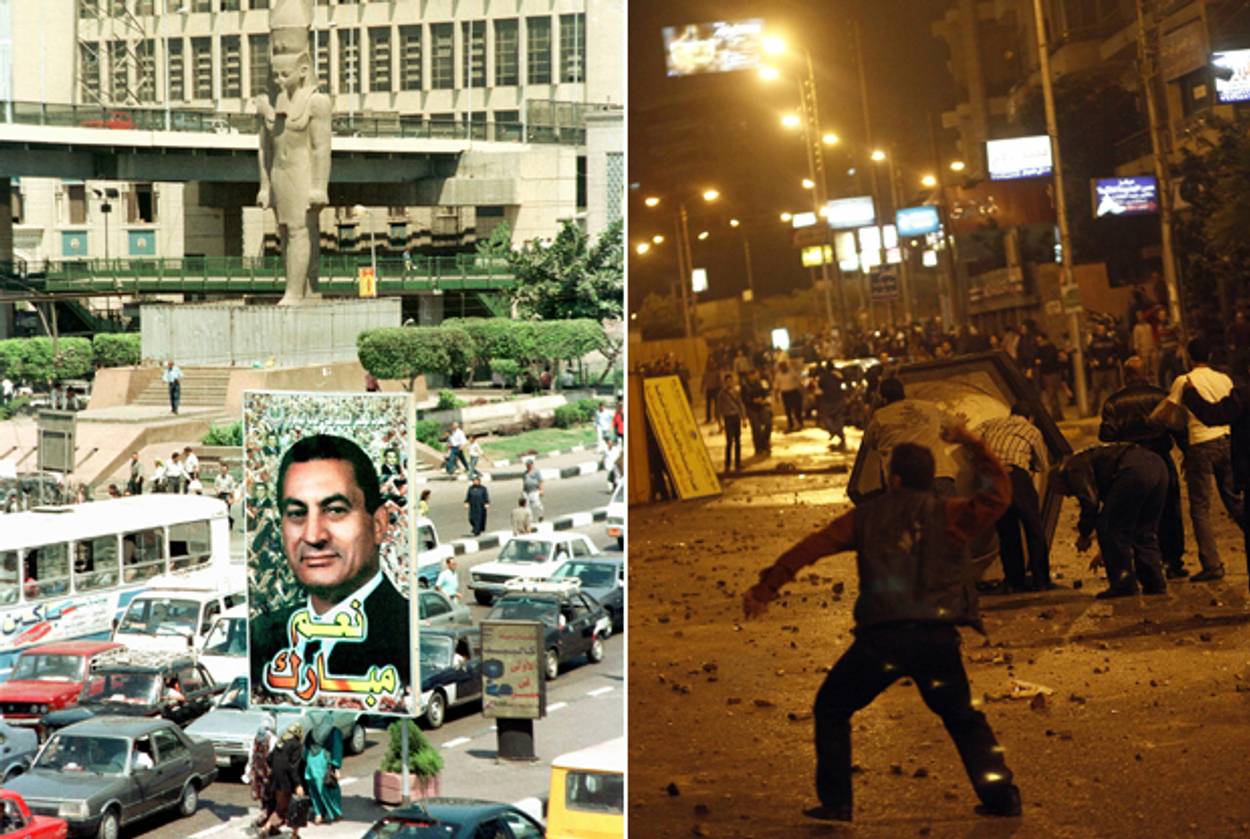

Mubarak had reduced what had once been a tempestuous land to a republic of silence and resentment. Mubarak kept the peace with Israel for three decades and gave the Pax Americana the intelligence cooperation he saw fit to provide, while snuffing out the democratic aspirations of his domestic critics and hauling off his rivals to prison. Morsi has thus reached for an old bag of tricks. But the fear of official power had been broken. The protesters returned to Tahrir Square to defy Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood behind him.

Regarding Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, and soon enough Syria, the question can be put starkly: Better the peace of autocrats and pharaohs, or the risks and uncertainties of unstable democracies?

This question has consumed Israelis since 1948. The Jewish state’s dilemma with its neighbors had always been sui generis; Israelis have lived with the siege that has marked their political life since the emergence of their state. But the Arab Spring has given this dilemma new power and relevance. The irony of a democracy unsettled by the fall of dictators on its borders derives from that uniqueness of Israel’s place in its neighborhood. That happy proposition that democracies make better neighbors, that benign view of history bending toward “perpetual peace” when there is internal tranquility in the life of nations—the reading of history we identify with Immanuel Kant—is a poor guide to the unforgiving politics of the greater Middle East. This is a Hobbesian world of perpetual strife and menace.

***

The indisputable truth is that Israel had not known until the Arab Spring what Arab democracies would bring forth. The accommodations it reached with its neighbors were always made with autocrats. The peace of Camp David, which blessedly put an end to major Arab-Israeli wars, was made by an autocrat, Anwar al-Sadat, and kept by another, Hosni Mubarak. Sadat had claimed divine inspiration for his peace, but the truth is that he had read the mood of his people—not the intellectuals and physicians and journalists and the engineering syndicate, who accused him of treason—but the ordinary Egyptians pressed by need and distress, unhappy that their country had to carry such a heavy burden on behalf of Palestine. He had gone to Jerusalem alone, and that journey would bring him acclaim abroad and peril at home and among the Arabs.

The treaty with Jordan, too, was the choice of a monarch, King Hussein, who was the sole decision-maker in his realm. Very few, if any, Jordanians embraced the peace or claimed it in broad daylight. “Civil society” remained surly and unalterably opposed; again the educated classes and the professional syndicates were at odds with this peace. In the shadows, intelligence operatives worked harmoniously with their Israeli counterparts, a businessman or two would speak well of the peace, but the accommodation with the Jewish state remained an orphan in the court of public opinion.

In the same vein, the peace of Oslo was concluded with Yasser Arafat, the undisputed master of Palestinian politics. He was at a great remove from the land, an exile in Tunisia, who had offended his Arab patrons and financiers by taking the side of Saddam Hussein when the Iraqi despot seized the principality of Kuwait and threatened to upend the order of nations in the Arabian Peninsula and the Persian Gulf. Palestinian society was not consulted about Oslo, and many Palestinian intellectuals dismissed the peace as a treaty of Palestinian surrender.

The Syrian-Israeli border has been its own tale. There was no journey to Jerusalem for Hafez Assad, or for his son Bashar after him. Hafez Assad seemed to savor the chess game with Israel’s leaders, hinting at peace but never concluding it. He belittled his Arab rivals as men who had sold out the sacred cause of Palestine. An Alawite of peasant origins in a country with a distinctly urban Sunni political tradition, he did well by his militancy and rejectionism. It was a sly game: The Syrian-Israeli border was by far the calmest of Israel’s borders, while Syria indirectly helped set ablaze Israel’s northern border with Lebanon. Less sure-footed than his methodical and unsentimental father, Bashar adhered to the same script for quite awhile. It took a great and tenacious rebellion by his own people to call into question the terms of Israel’s relationship with Syria.

In the Syrian refugee camps in Antakya a few months ago, more than one erstwhile nationalist raised on a diet of anti-Zionism wondered aloud to me about the prospect of the Israeli air force putting an end to the barbarism and the cruelty by reducing Bashar’s presidential palace and bunker to rubble. Israel has big stakes in the outcome of this civil war but little leverage over the play. Israel’s most authoritative interpreter of Syria, the historian and former diplomat Itamar Rabinovich, believes Israel should take a measured risk by building “discreet channels” to the Syrian revolutionaries and preparing for the morning after the fall of the despotism. The rebels may bring with them to power the rejectionism that has animated Syria’s view of this struggle: Palestine is “Southern Syria,” is the orthodox view. No deliverance is certain, and there is no guarantee that the new masters of Syria would not turn up pressing their case for sovereignty over the Golan Heights. But the cease-fire brokered by Henry Kissinger, back in 1974, is now in the wind.

***

On the surface of things, the fall of the dictators and the tumult that has followed appear to bode ill for Israel. But we should look unflinchingly at the dictatorships’ harvest: the major wars fought in the region,and its overall militarization, should offer sobering evidence that the dictators needed and fed and endless conflict. Natan Sharansky, with the clarity given him by nine years in the Soviet gulag, has given the linkage between peace and the internal arrangements of Arab societies its most sustained and provocative discussion. With all of Israel’s security dilemmas laid out before him, Sharansky would forgo the tyrant’s peace for the turbulence of democracies. With Cairo’s streets politically aflame, and as the Mubarak dictatorship was on the verge of collapse, in a compelling interview with David Feith in the Wall Street Journal in February 2011, Sharansky rejected the stability offered by autocrats. Theirs is a false gift, he said. They rule and terrorize but increase the hatred toward “America and Israel and the free world.” Genuine peace should rest not only on how regimes conduct themselves abroad, but also on their treatment of their own people. No free pass for the tyrants; Sharansky is willing to brave it: The democracy that hates you, he says, is much better than the dictator who loves you.

Israel has no choice but to wait out these rebellions of the Arab Spring. Fundamentally, these are the revolts of Arab populations who have wearied of the waste and fraud of the dictatorships. The rebels know that the anti-Zionism of the dictatorships was an alibi for failure, pure scapegoating. One needn’t be as brave as Sharansky to place a wager on these rebellions, to trust people with their history.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Fouad Ajami is a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution and the author of The Syrian Rebellion.

Fouad Ajami is a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution and the author ofThe Syrian Rebellion.