Hitler’s Jewish Soccer League

A new documentary exposes the football team of the Terezin ghetto—part of the Nazis’ strategy to fool the world

In 1939 there were hundreds of professional soccer clubs playing in every country in Europe. But as Hitler’s war swept the continent, clubs shuttered as players everywhere were called up to combat. Amazingly, one of the only places that maintained a soccer league during World War II was the Terezin ghetto—arguably the strangest of the Nazi transit camps and ghettos—where, under German imprisonment, professional and amateur Jewish players were allowed to organize and self-administer a vibrant soccer league: Liga Terezin (Terezin League). There, in the fortress and garrison town of Terezin, 40 miles northwest of Prague, hundreds of games with dozens of players were played between 1942 and 1944. For the Jews, it was a matter of survival; for the Nazis, it was part of an overall strategy designed to fool the world.

But many have never heard of the league, perhaps due to the musical, literary, and artistic legacy that Terezin’s prisoners left behind. A new documentary film is setting out to change that. Liga Terezin which was aired for the first time on Israeli television on this year’s Holocaust Remembrance Day, tells the story of the league through the perspective of its survivors and their relatives. The backbone of the film is extensive coverage of a game that took place on Sept. 1, 1944—just weeks before most of the players were sent to extermination camps. (Approximately 160,000 Jews passed through Terezin, of whom 35,409 died while in the ghetto; 88,129 were deported to extermination camps, and of these, just 4,136 survived.)

Take the story of Paul Mahrer, who was imprisoned by the Nazis in Terezin after the German occupation of the Sudetenland. He had played soccer for the Czechoslovakian national team, including two games in the 1924 Olympics, and then played on several teams in the United States before returning to Czechoslovakia in the 1930s. Though already over 40 when he was brought to the ghetto, he was still a well-known sports figure and ended up playing in Liga Terezin with the other Jewish workers. His “salary” as a player was the ability to obtain better food portions. He survived the war and ended up in the United States, where he died in 1985.

“Soccer saved my family’s life,” his 25 year-old great-granddaughter, Dani Mahrer, told me last week in Jerusalem.

***

Liga Terezin is the product of a love of soccer and a chance meeting between Oded Breda, the nephew of one of the league’s players, and Israeli television journalists Mike Schwartz and Avi Kanner, who became the co-directors of the film. All of them discovered quickly that they had two things in common: a great interest in commemorating the Holocaust, and their affection for soccer.

The film’s origin story begins with a photograph. In the early 1960s, a distant Argentinian relative brought a picture of Pavel Breda—a prisoner in Terezin who played in the ghetto’s soccer league—to his brother Moshe Breda in Israel. Moshe, who was lucky enough to get one of the few British certificates available for entry to Palestine in December 1939, shared the picture with his young son, Oded, on whom it left a lasting impression: “From the first day I saw this piece of paper with my uncle on it, this piece of paper virtually haunted me,” Breda told me. “What happened over there?”

Breda, 59, who never misses his twice-a-week soccer game, lives in Ra’anana. A hi-tech refugee, he now runs Beit Terezin, located at Kibbutz Givat Haim Ihud between Haifa and Tel Aviv, which commemorates the memory of the Terezin Ghetto and houses a museum and archives holding thousands of original artifacts from the ghetto, including extensive documentation of the Terezin soccer league. “What brought me to the subject of the Holocaust,” he said, “was soccer.”

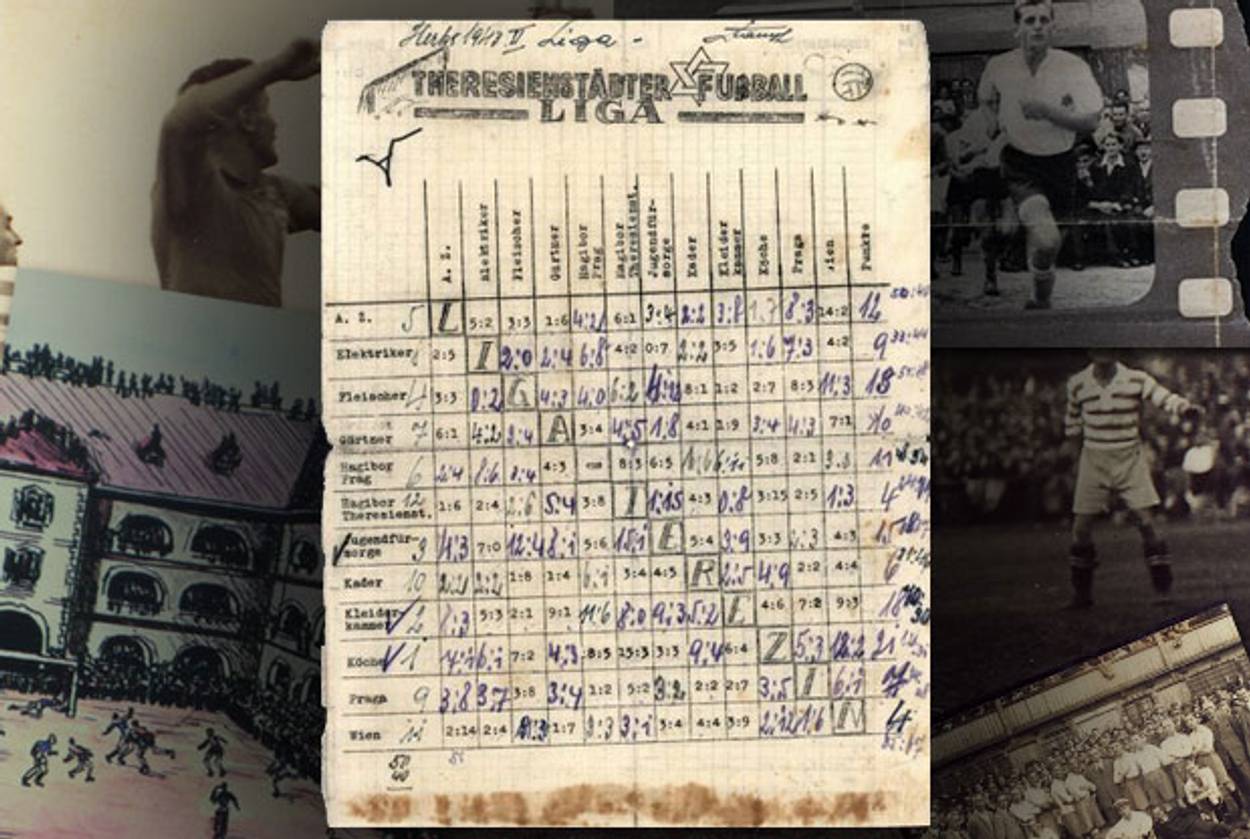

Breda remains struck by the detail that was paid to the league’s organization. Liga Terezin had league management, working committees, and professional referees. It published league results, standings, and statistics in the sports pages of makeshift ghetto newspapers, all written by the Jewish children of the ghetto. There were at least a dozen teams in the league in each of the three years that it operated, and players generally represented the areas in which they worked. (One ledger read “Clothing Warehouse vs. Youth Counselors.”) Others took on the names of their favorite professional teams. Every game had thousands of Jewish prisoners who packed Terezin’s enclosed Dresden barracks, which emulated a soccer stadium.

Toman Brod, a Czech author and retired professor of history, was 13 years old when he watched soccer games in the ghetto at Terezin. He says in the film that “football was a matter of pleasure—and we needed some pleasure in our desperate lives. It was very important not to lose our self-confidence and our self-dignity. It was crazy, but it was reality.”

***

To understand Liga Terezin, one must put the league into the context of the unique combination of the nature of the ghetto’s population and the Nazis’ cynical use of the Jews who were imprisoned there. “There was no other camp like it,” Rabbi Norman Patz, president emeritus of the Society for the History of Czechoslovak Jews, told me. “Terezin was the Nazis’ show camp, cynically designed to deceive the world and to conceal their genocidal plans. And over the four years it was in operation, the cream of Europe’s Jewish intellectual and cultural communities, starting with Bohemia and Moravia (today’s modern-day Czech Republic), passed through it.” While the Nazis may not have intended to send artists and scholars to Terezin, the reigning culture of central European Jewry at the time created an especially creative atmosphere in the ghetto.

Terezin was chosen by the SS in 1941 because, as an enclosed fortress town, it was ideally suited to be turned into a transit camp and ghetto. By the spring of 1942, the last of the non-Jews living in Terezin were expelled by the Nazis, creating a closed Jewish environment. Food was scarce and living conditions even worse. Although the military barracks and the houses of the civilian population normally accommodated about 7,000 people, the number of prisoners in the ghetto climbed to well over 50,000, reaching a peak of 58,491 in 1942.

Deborah Lipstadt, professor of Jewish and Holocaust Studies at Emory University, cautions against the impulse to put Terezin in a different category than the approximately 20,000 other transit, forced-labor, concentration, and extermination camps set up by the Nazis during 1933–1945. “Sometimes people think about Terezin differently just because an opera or Verdi’s Requiem was performed by the inmates there, but the conditions were very hard.” As they did in other European ghettos, the Nazis forced a Jewish council to nominally govern the internal affairs of the camp. Despite the enormous hardships—16,000 Jews perished at Terezin in 1942 alone—the Jewish leadership succeeded as best it could in taking care of education, the welfare of children and youth, food distribution, work, etc.

The extent of cultural activities at Terezin is well known and includes a long list of famous composers, musicians, actors, and artists, most of whom were ultimately sent in transports to their deaths. There were at least four concert orchestras as well as chamber groups and jazz ensembles; stage performances were produced and attended by camp inmates. The book University Over the Abyss documents the story of 520 lecturers and 2,430 lectures that were given at Terezin between 1942 and 1944.

The Nazis allowed Jews to have plenty of activities after working hours, “and why not,” said Rabbi Patz. “The Nazis figured it didn’t matter; the Jews were all going to die anyway.”

There was another reason why the Nazis allowed Jewish cultural life to flourish: During the latter part of 1943, 456 Jews from Denmark were sent to Terezin, including Jewish children whom Danish organizations had been attempting to hide in foster homes. Denmark’s King Christian and other Danish leaders insisted that the Danish Red Cross visit the deportees in order to see firsthand their treatment in Terezin.

Preparations for the visit took many months. Overcrowding in the ghetto was alleviated somewhat by a “beautification action” in which 17,517 people were deported to a “family camp” at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Gardens were planted, houses were painted, and buildings were renovated.

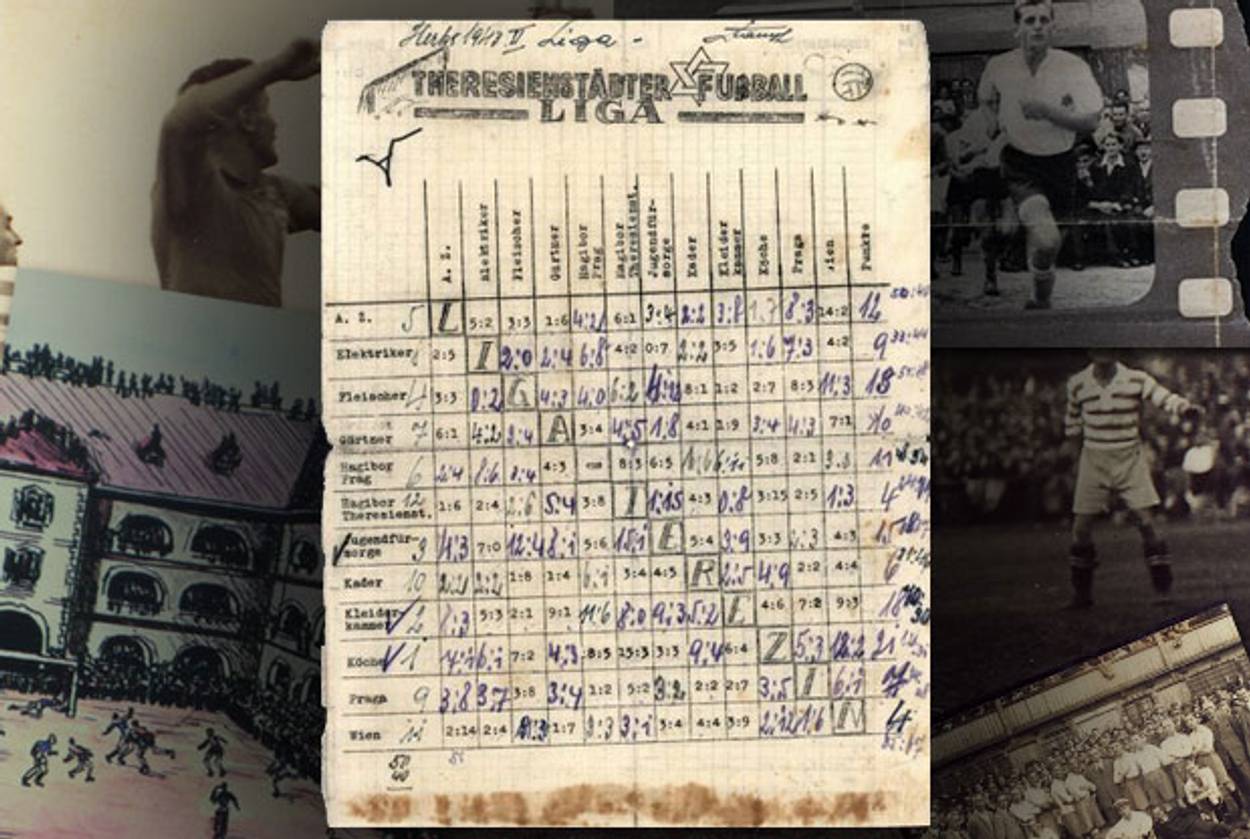

On June 23, 1944, two delegates from the International Red Cross and one from the Danish Red Cross visited the ghetto. A soccer game was played in the courtyard of Terezin’s Dresden barracks with cheering crowds looking on, and “Brundibar,” a children’s opera, was performed for the visitors in a community hall built specifically for the occasion. The inspectors were completely taken in by the ruse.

Parallel to the preparations for the Red Cross visit and even after, the Nazis made a propaganda film directed by prisoner Kurt Gerron, a famous German Jewish director and cabaret star, called Theresienstadt—Self-Administration of Jewish Settlement. (The Jewish inmates ironically called it Hitler Gives the Jews a Town.)

The shooting of the propaganda film was completed in early September and featured prominently—perhaps half of the film—the Liga Terezin game played on Sept. 1, 1944. Within six weeks, the players, fans, most of the cast, and Gerron himself were deported to Auschwitz, and most of them were gassed. “Almost all the people you see in the movie were dead between four and six weeks after the film was made,” said Breda. And his Uncle Pavel? “He died of starvation in a labor camp before the war ended.”

Though the Nazis never ultimately screened the completed film, snippets from two copies of the film—one 18 minutes long, and the other 23—were recovered. Individual players, including Breda’s uncle, are clearly visible throughout the match.

Dutch Historian Karl Margry, who has extensively studied the Nazis’ Terezin propaganda film, was interviewed for Liga Terezin: “The surprising thing is how long the football sequence is. It makes football in Theresienstadt look more important than it was, which is part of the propaganda idea behind it. The SS realized that football is something that not just the people in the ghetto, but people all over the world liked.”

Soccer fans often call the sport “the beautiful game.” And for the Jews in the Terezin Ghetto, it actually may have been. What Liga Terezin shows, according to co-director Schwartz, is that the prisoners “weren’t just sitting around waiting to die—they did things.” Added Breda, “Our job in the film is to tell the story of this league—a story of life and not of death.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for ourDaily Digestto get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Todd Warnick is a consultant and freelance writer living in Jerusalem. He also refereed basketball for more than 30 years, including 25 years in professional leagues in Israel and Europe.

Todd Warnick is a consultant and freelance writer living in Jerusalem. He also refereed basketball for more than 30 years, including 25 years in professional leagues in Israel and Europe.