Remembering Tech Titan Danny Lewin, the Fighting Genius on Flight 11

The first victim of the 9/11 attacks was a veteran of an elite IDF unit, as well as an innovative Internet entrepreneur

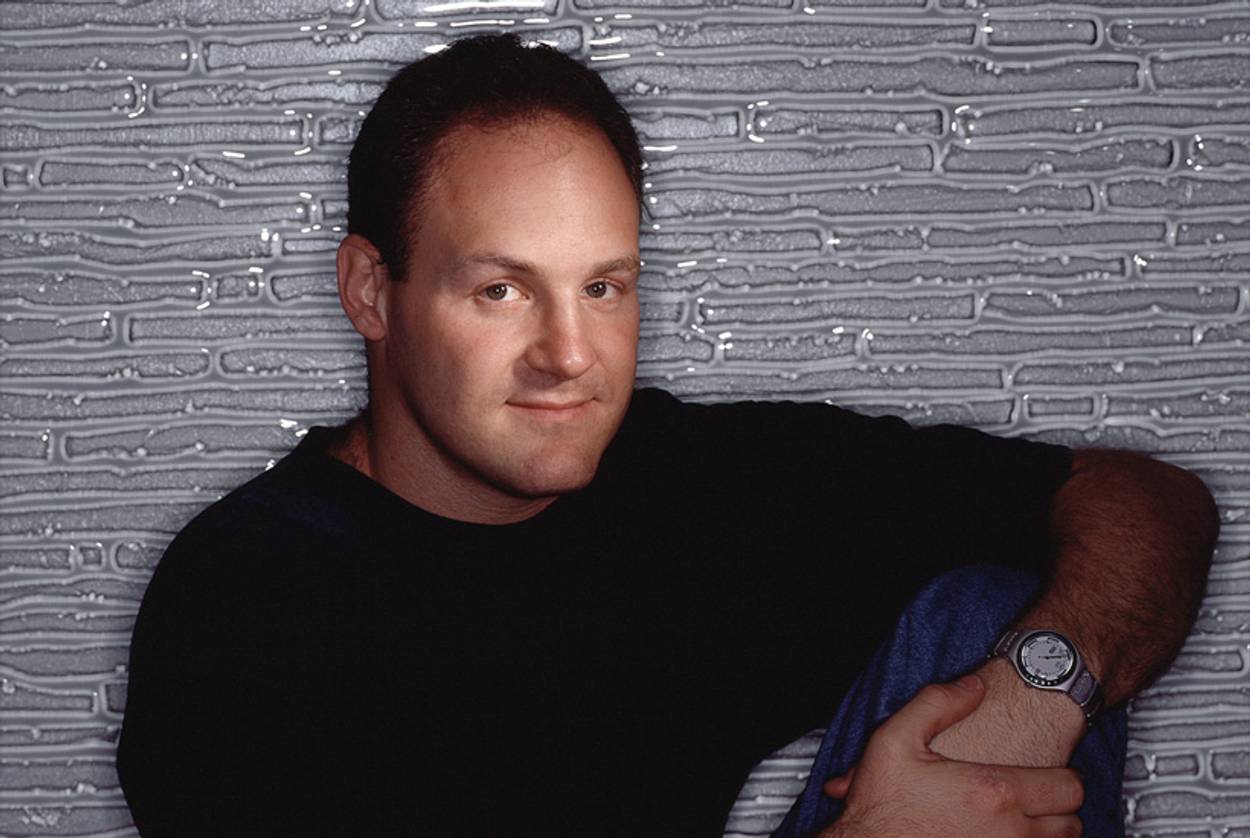

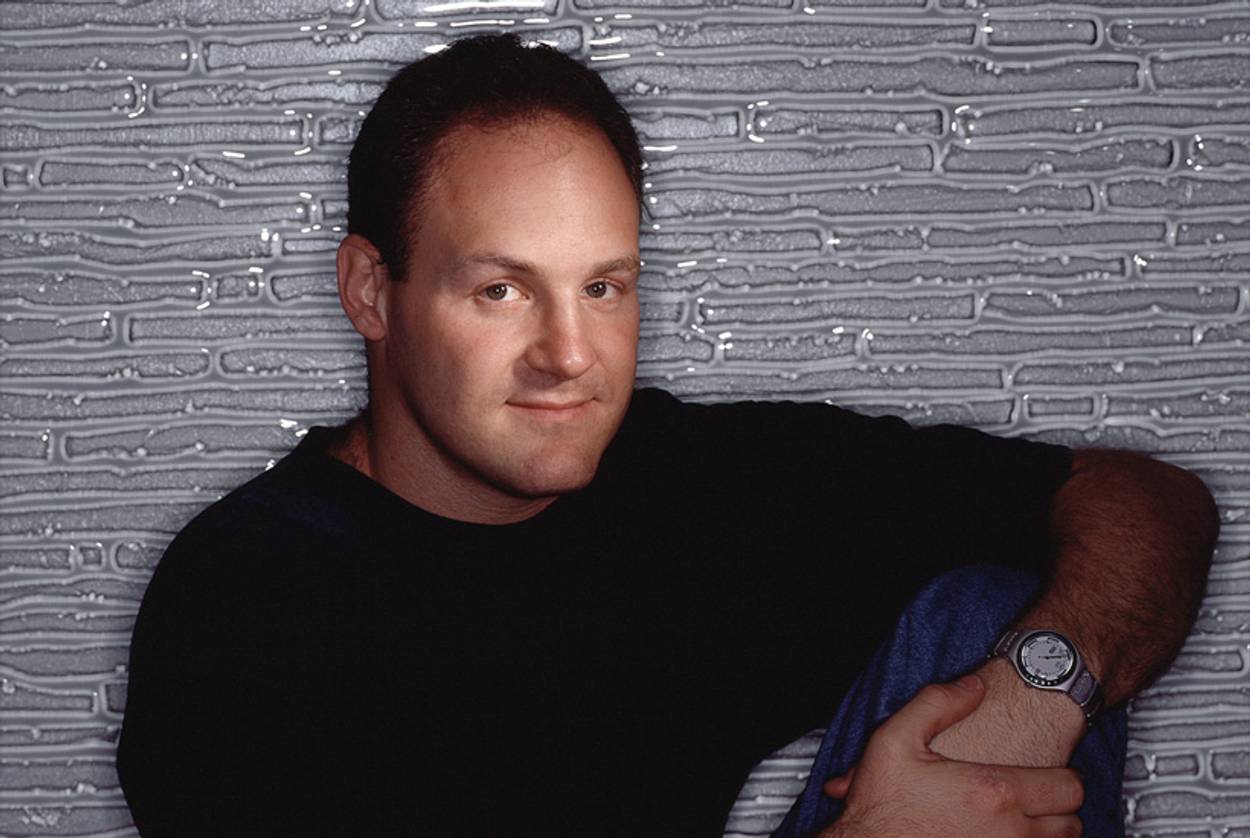

By most accounts, Danny Lewin was the first victim of 9/11. Seated in seat 9B aboard American Airlines flight 11, he saw Mohamed Atta and Abdulaziz al-Omari, sitting just in front of him, rise and make their way to the cockpit. According to calls from flight attendants to air traffic officials, later documented in the 9/11 Commission’s report, Lewin wasted no time in acting. Having served as an officer in Sayeret Matkal, the Israel Defense Forces’ top unit, he moved to tackle the terrorists. The man in 10B, Satam al-Suqami, moved, too, producing a knife and slitting Lewin’s throat. Less than 30 minutes later, at 8:46 a.m., the plane crashed into the World Trade Center’s North Tower.

Elsewhere, in America and all over the world, people desperate for accurate information turned to the Internet for news. Straining under the overwhelming demand of tens of millions of simultaneous requests, the web’s biggest news sites threatened to collapse. Very few did, thanks in large part to the technology that Lewin himself had developed years earlier: Although only 31 at the time of his murder, he was the co-founder of Akamai, a pioneering technology company whose content routing solutions enable the seamless flow of nearly 20 percent of the web’s traffic.

As a terrific new biography of Lewin—No Better Time, by Molly Knight Raskin, released this week—demonstrates, the tenacity that the young entrepreneur displayed in his last moments was the same intense force that propelled him to tech titanhood. Born in Denver, he moved to Israel with his parents at 14 and quickly found high school insufficiently stimulating. Frequently keeping just one step ahead of the truancy officer, he skipped classes to work out at a local gym, eventually winning the title of Mr. Teenage Israel in a coveted bodybuilding competition. When the time came to join the army, Lewin had no doubts about where he belonged—it had to be the best.

Even in Sayeret Matkal—the legendary commando unit that bred virtually all of Israel’s modern-day leaders, from Ehud Barak to Benjamin Netanyahu—Lewin stood out. Making a shiva call after Lewin’s murder, for example, one army buddy recalled observing Lewin during one exhausing drill and being surprised by noticing the usually fit runner lagging a bit behind. When the friend asked Lewin if everything was alright, the latter smiled and said that he found the unit’s training insufficiently rigorous and had therefore decided to challenge himself and pack his bag with twice as much weight.

After four years in the IDF, Lewin, now married and with child, enrolled in the Technion, often described as Israel’s MIT; he was brilliant enough to eventually gain admittance, with full scholarship, to the real thing, moved his family to Cambridge, and began his doctoral studies in computer science. After winning an award for best thesis, he partnered with one of his professors, Tom Leighton, and decided to enroll in a university-wide competition for fledgling start-ups. His algorithms, he believed, had the potential of revolutionizing the Internet, as they could manage data traffic in a way that was considerably faster and more efficient than anything available at the time. Others weren’t as convinced: Lewin and Leighton failed to win any of the competition’s top spots. Their ideas, argued an academic colleague, had no practical applications.

Lewin, however, was undeterred. Making the rounds among Boston’s numerous venture capital firms, he eventually raised enough interest and money to launch his company. Walking with Leighton near their Cambridge offices one day, Lewin told his former professor that he had no doubt that Akamai, as they now called their company, would be a success: It wasn’t just that they had the best technology, he said, or the best people, but because they would never, ever quit.

But if dogged dedication played a large part in Akamai’s success, so, as it always does, did luck. On March 11, 1999, two events coincided to make traffic online swell, one being the opening of the NCAA basketball tournament and the other the official release of the long-awaited trailer for the brand-new installment in the Star Wars saga. With the web still in its infancy, few sites had the infrastructure to handle such a tsunami of clicks, and fans nationwide were grumbling about their inability to follow their favorite teams or peek at the new adventures of the Jedi. Amid the general discontent, however, a few reporters noticed that the only sites that didn’t collapse were those served by Akamai’s technology; the very next day, the company was inundated with new, top-tier clients.

What follows is a familiar story of web ebb and flow: a stellar IPO, making Lewin and Leighton and their co-founders paper billionaires; a tailspin following the tech bubble’s burst; and restructuring en route to recovery. On Sept. 10, 2001, Leighton and Lewin met until late at night, agonizing over having to fire hundreds of employees but certain that their new strategy would allow Akamai to continue and flourish.

It did, but Lewin, tragically, wasn’t there to see it. Reading his new biography, and reflecting on his life, one cannot help but wonder what might have become of him had he not taken his seat, 9B, still talking to one of Akamai’s lawyers as the flight attendants asked him to put away his phone. Would he have joined the ranks of Sayeret Matkal graduates who rose to the office of prime minister? Would he have joined Jobs and Zuckerberg and Gates in the pantheon of immediately recognizable innovators? Lewin himself, it seems, would’ve abhorred such futile thought exercises. Instead, he leaves behind not only a singularly important technology, but also a legacy that urges us, as he had urged himself, to rise up, work harder, demand better, and believe that everything is possible. As we move further and further from the historical events of Sept. 11, 2001, it’s that spirit—the spirit that was uniquely Lewin’s but that also represents all that is great and eternal and undeniably American—that must remain strong.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.