Lyndon Johnson Was Scheduled To Visit My Austin Shul the Day After Kennedy Died

But in December 1963, the new president made up the date, honoring a long Jewish friendship

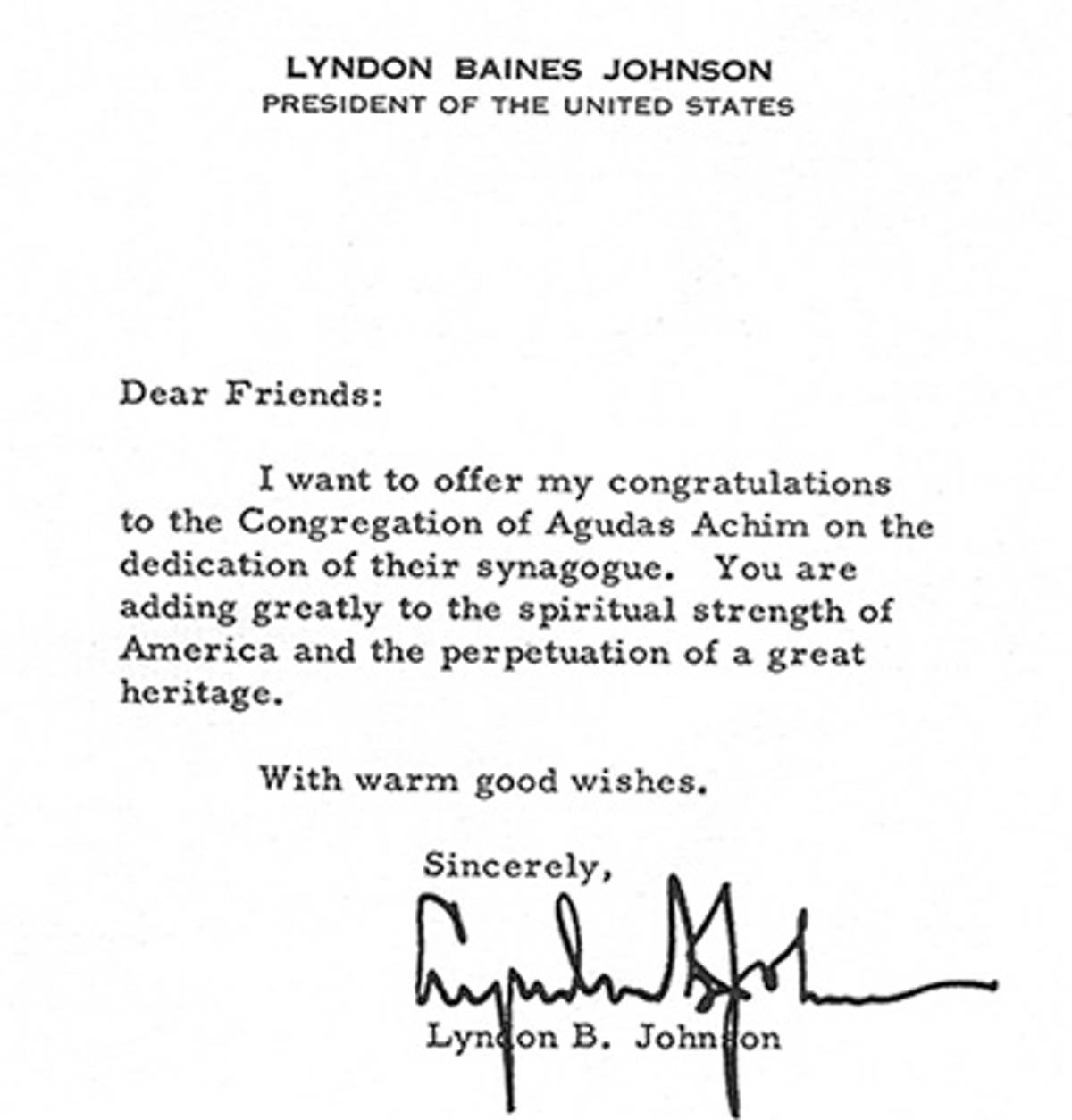

On Nov. 22, 1963, the women of the Congregation Agudas Achim Sisterhood in Austin, Texas, were working in their new kosher kitchen, mixing potato salad for the several hundred people expected to turn up at the dedication of their new synagogue the next day—a group that was to include Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, formerly the congregation’s longtime congressman. The women didn’t have enough mixing bowls, so they wound up using the synagogue’s brand-new plastic trashcans to prepare the potato salad, a detail their honored guest would never need to know.

Of course, Johnson never made it to Austin. Instead of holding a joyous celebration, the congregants gathered to mourn the death of John F. Kennedy and pray for their old friend Lyndon, who had just been sworn in as president on Air Force One, standing next to the blood-spattered and shocked former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy. No one expected that he would reschedule his visit—but, ever the consummate politician, Johnson decided to keep his promise, and on Dec. 28, the new president arrived at the new Agudas Achim building.

The synagogue owed its new location on Bull Creek to Johnson’s intercession in a real-estate deal. It’s highly probable that no American president has ever been as intimately involved in the construction of a shul as Johnson was in this one. In October 1963, as vice president, he loaned his Lincoln Continental convertible to congregant Morris Shapiro, who drove the Torah scrolls the three or four miles from Congregation Agudas Achim’s downtown location to its new suburban home amid a parade of marching Jews.

The connection between Johnson and Agudas Achim was Jim Novy, a Polish-born immigrant who wound up in Texas under the Galveston Plan and made a small fortune in scrap metal. One of Johnson’s earliest political allies in Austin, Novy, pillar of Austin’s Orthodox congregation, was instrumental in building the synagogue. For many Austin Jews, their relationship with Johnson had been so close that he was almost too familiar; Milton Simons, who was Agudas Achim’s president in the autumn of 1963, recalled that some of the congregants knew the vice president so well they refused to pay to hear him speak at the synagogue dedication.

The assassination changed that: When the dedication was rescheduled, a gully wash of people from all over the country wanted in, offering what Simons described as “enough money to pay the mortgage,” just to come to Austin to hear the new president talk to the Jews. In the end, it was Novy who kept the strangers out: As far as he was concerned, Austin Jews were LBJ’s Jews, and even “the people too cheap to buy tickets,” in Simons’ estimation, should be there to hear the new president’s first non-official public remarks as president.

I first encountered the story of the synagogue dedication in 1988, while writing a book about Texas Jews. In 2000, when Agudas Achim moved to its current location at the Dell Jewish Community Campus, I volunteered to produce a video to mark the occasion and interviewed congregants who attended the 1963 event, many of whom have since passed away.

Johnson had a special place in his heart for Jim Novy. Their relationship likely began in the early 1930s, when Lyndon worked as secretary and go-to man for Rep. Richard Kleberg, a member of the King ranching family who preferred polo to politics and gave Johnson wide berth. He became a regular presence at meetings of the B’nai B’rith Lodge and Zionist groups. It’s not clear whether Novy made his way to Washington to advocate for Zionist causes, as his daughter Elaine Shapiro believes, or to sell scrap metal to the federal government, as a distant cousin, Benard Laves, told me, but either way, he returned with a lifelong friend.

When Johnson moved back to Austin in 1935 to serve as Texas director of the National Youth Corps, he set up his office at 6th Street and Congress Avenue, at what was then the intersection between high-end Austin and the Jewish-owned schmatte stores along 6th Street. When it was time to raise funds to support Johnson’s first run for Congress, in 1937, the B’nai Brith members and Zionist activists Johnson met at Novy’s lake lodge.

Laves, a born raconteur, remembered walking up 6th toward Congress as a child with his father. He spotted Johnson and wanted to meet him, but his father cautioned, “Just let Lyndon alone to do his thing.” That day, LBJ walked with Jake Pickle, the advertising man who would eventually succeed him as representative of the Tenth District. Jake called to Benard’s father, “Hey, Louie!” He escorted LBJ across the street to greet them. “This great big tall guy, I’m a little kid looking up at him, this terrible look on his face, meaner than hell,” Laves recalled to me in 2009. (He died earlier this year.) “And all of a sudden he smiled, and it was like the sun coming out from behind a cloud.”

Johnson’s constituents in the 10th District included all kinds of minorities: blacks, Mexicans, and immigrants from dirt farms who spoke English, Spanish, Czech, German, and Yiddish. It was a time, as Johnson recounted to the congregation in December 1963, when newspapers were published in a dozen languages to serve Austin’s many immigrants. The vast majority of Austin’s Jews were Democrats, and when Austin’s Jews were troubled about something or needed help, Johnson answered their calls and got results.

But it was his strong and enduring relationship with Novy that led to a sweetheart land deal in the early 1960s by which Congregation Agudas Achim sold its downtown building to the federal government and then applied the proceeds to land along the Missouri Pacific railroad easements that ran through the new suburbs of north Austin. Today, Austin’s Federal Building stands at the site of the old synagogue.

Early one morning after the sh’loshim for Kennedy were over, Novy received a call from President Johnson. “He told Daddy, ‘I said I would be there, and I’m going to be there,’” Elaine Shapiro said. With only a week’s notice, the members of Congregation Agudas Achim hustled once again to prepare. The shul’s decorations committee set the stage for the possibility that there might be television cameras in attendance. The Sisterhood catering team thawed out the barbecue and remade the potato salad and Jell-O mold. Shirley Rubinett remembered that the Secret Service sent taste-testers, and the president was supposed to eat only what they approved. But, in the end, she told me, “He ate whatever he wanted, he gobbled it down, he was hungry.”

Almost every person I spoke with said the most memorable image of the evening was entering the synagogue vestibule and seeing a red telephone on the table—a cultural icon preserved in the congregants’ collective memory as the infamous “red phone” connecting Washington and Moscow, though it could not have been. Ann and Saul Ginsburg’s son, David, played “Hail to the Chief” on the Spinet piano. The suave and articulate Dr. Polsky emceed the evening, and Jim Novy introduced the president with a litany of stories of all the times Johnson had helped him and the Jews. “I’ve always called on President Johnson to give us a help,” Novy told the crowd. “And there was never a time that I asked the president that he wouldn’t take care of Jewish problems.” In fact, Novy’s introduction that night is what gave rise to the persistent Internet rumors that Johnson was a righteous gentile who saved hundreds of Jewish lives before and during WWII, though exhaustive searches by Johnson Library archivist Claudia Anderson have turned up no primary-source proof to substantiate the rumors.

After the community poured out its affection, President Johnson rose to speak. In his remarks—captured on a 33 1/3 LP for congregants to keep as a souvenir—he revealed the reciprocity of the trust and respect he felt, as well as the strength he drew from them. He combined a tribute to his home community and the Jewish people with remarks that foreshadowed his War on Poverty, which we Texans chose to hold in our memories in a more elevated place than the missteps in Vietnam that ultimately doomed his leadership. And he offered his personal tribute to Jim Novy: “If we have leaders like this good man who has spent so many of his hours in the years past trying to build temples like this, temples where men can worship, temples where justice reigns, temples where the free are welcome, temples where the dignity of man prevails, then America will truly be worthy of the leadership we claim, and the rest of the world will follow us where we lead.”

When Novy died, in 1971, Johnson—by then out of the White House and back in Texas—sat alone in the back of the sanctuary, without Secret Service or aides or hangers-on, wearing a kippah. Shortly after, Johnson also died of heart disease. It would seem that the partnership forged by the two men and the benefits yielded to Congregation Agudas Achim had come to an end. But there is a postscript to this story: During the later years of the Johnson presidency, Encyclopedia Judaica approached Jim Novy to see if he could persuade the president to help fund them. Through Novy’s influence, they were able to obtain an interest-free $2 million loan to conduct the research needed to replace the old Jewish Encyclopedia with a version that reflected both the Holocaust and the birth of the State of Israel. In return for the favor, Novy asked for 100 sets of encyclopedias to sell as a fundraiser. The proceeds arrived after the deaths of both Johnson and Novy, but Dr. Byron Smith, another former shul president, hoarded the money and hid it from anyone who wanted to use it to pay for day-to-day operations to pay down the Bull Creek mortgage, years in advance.

We Texas Jews just loved LBJ. It wasn’t just that he helped Austin Jews build a shul or that so many of us benefited from the “kosher pork” Johnson brought home. (My father was a chemical engineer who worked to make solid rocket fuel to be sold to NASA.) I remember how, on the day Johnson was inaugurated in 1965, my father proudly pointed to Rabbi Hyman Judah Schachtel of Houston standing right there next to the president of the United States. To have my grandparents’ rabbi make the invocation gave a 10-year-old Jewish girl from Waco a sense of belonging. A few years later, in 1971—the year Jim Novy died—I attended a youth gathering at the Religious Action Center in Washington, D.C., and for the first time heard my peers characterizing LBJ as a warmongering ignoramus with a drawl. To this day I hear the echo of my kishkes: Didn’t they know? Didn’t they know that LBJ was one of us?

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to reflect that President Johnson was not, in fact, the first sitting American president to dedicate a synagogue. That honor belongs to President Ulysses S. Grant, who attended the dedication of Washington’s Adas Israel in 1876.

Cathy Schechter lives in Austin. She is the co-author of Deep in the Heart: The Lives and Legends of Texas Jews, and wrote the first article about Austin for the Encyclopedia Judaica. She is at work on a novel.