Ariel Sharon: 1928-2014

One of Israel’s legendary military commanders and most influential politicians leaves a legacy that was nearly great

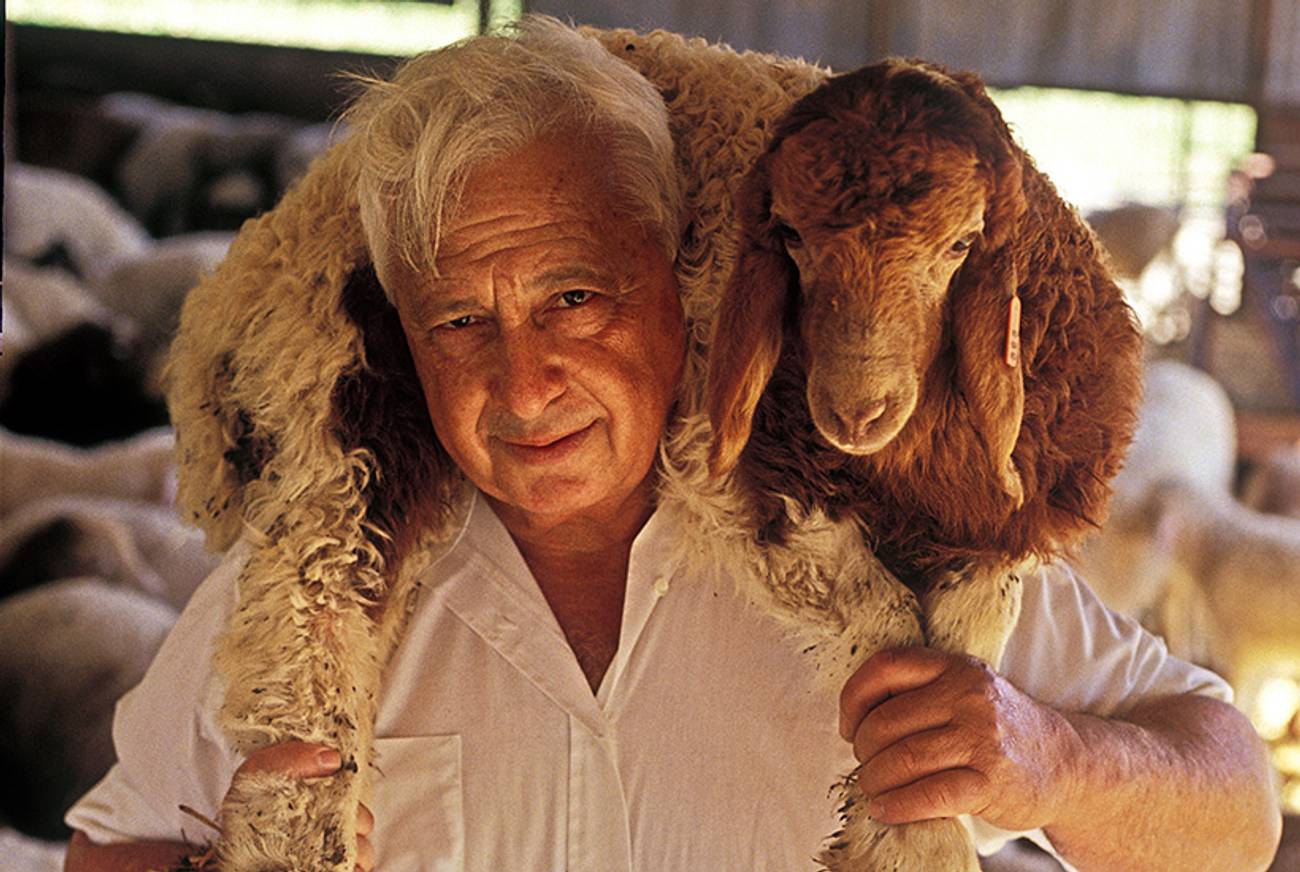

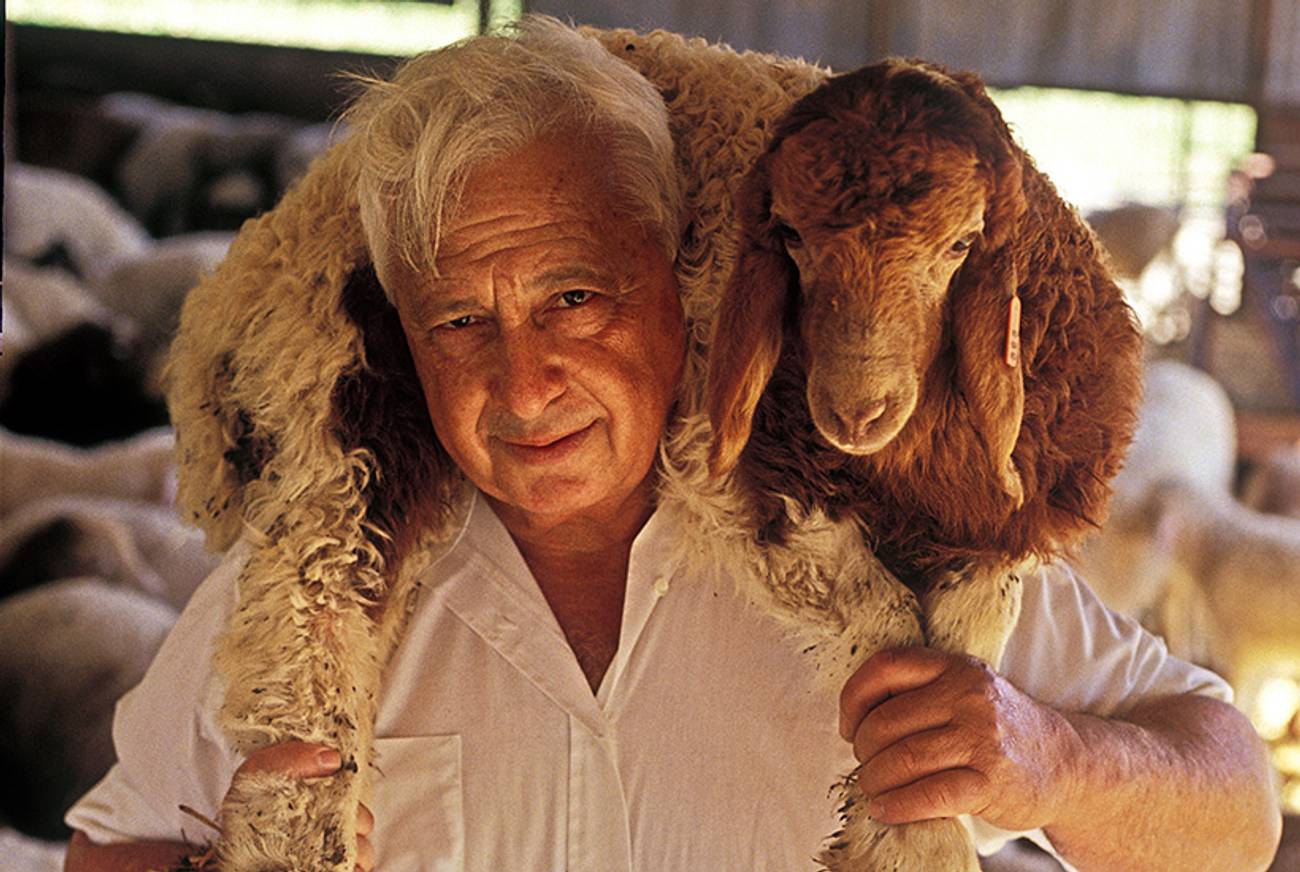

Some years ago, a cameraman proposed to Ariel Sharon that he photograph him holding a sheep. As the photographer later told it, one of Sharon’s sons, Gilad, who was on hand, advised against it. But Sharon, then about 70, thought about it for a moment and then agreed. The picture became iconic: the politician, flanked by animals, standing on hay in rough brown boots, a sheep slung over his shoulders.

Sharon agreed because he liked the image of farmer-general, à la Cincinnatus, the fifth-century B.C.E. Roman who abandoned the plow to lead the legions in defense of the republic and then returned to his humble plow. (Sharon’s plow, incidentally, was not so humble—a thousand-acre farm, Havat Shikmim, in Israel’s south, practically the only such spread in Israel.) Also because David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s founding prime minister and great leader, had once, famously, been photographed holding a lamb. And, of course, because Sharon was something of a showman. During his now-legendary military exploits, he took care to be photographed from every angle. (Photographs of Gen. Sharon in the Yom Kippur War of 1973, with a white bandage wound around his head, are also iconic.)

But while Sharon grew up in the agricultural village of Kfar Malal, northeast of Tel Aviv, and loved running Havat Shikmim, which he bought in 1972, sheep-farming was really a pastime, as was Ben-Gurion’s sojourn in rural Sdeh Boker. The passions that consumed Sharon throughout his 85 years were the army, in which he served more or less continuously from 1947 until 1973, and politics, where he starred from 1973 until 2006, when he suffered a brain hemorrhage and fell into a coma while serving as prime minister.

Sharon, perhaps, had hoped to follow Ben Gurion into the ranks of “great”—and he might have made it had illness not cut his career short. To be sure, he manifested military greatness during his years in the Israel Defense Forces. True, in the early 1970s, political, disciplinary, and personal calculations had blocked his appointment as chief of the general staff of the IDF; he was always seen as uncontrollable and something of a maverick and distrusted by the powers that be. But in his decades of service, he clearly demonstrated his mettle as the IDF’s best field commander. From 1953 to 1955, as the leader of Unit 101 and then of Paratroop Battalion 890, Sharon fashioned the ethos and tactics of IDF commando operations. In the 1967 Six Day War, Sharon, by then a divisional commander, brilliantly conquered the Umm Katef-Abu Agheila Egyptian fortification complex in the Sinai. In 1970 and 1971, as OC Southern Command, he successfully uprooted Palestinian guerrillas—terrorists—from the Gaza Strip, a campaign that often involved brutal tactics. (A retired Israeli police chief once told me that he had witnessed Sharon personally executing a captured terrorist in Gaza prison’s courtyard.) In 1973, overcoming some hesitancy among his superiors, Sharon led the game-changing assault across the Suez Canal that forced Egypt, which had launched the Yom Kippur War together with Syria, to beg for a ceasefire.

In politics, too, he had repeatedly exhibited both his maverick streak and his bulldozer credentials. He got things done, whatever the legal and practical impediments, and often he got them done in his own way. But his political legacy remains ambiguous on a number of levels.

A product of the Labor movement, Sharon was a Mapainik at heart: Mapai was the pragmatic socialist party, led by Ben Gurion, that had led the Zionist enterprise to statehood and ruled Israel between 1948 and 1977. But in 1973, Sharon jumped ship and helped bring Menachem Begin’s Likud—then called Gahal—to power. From the late 1970s into the 1990s he was instrumental in expanding Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Gaza—though in 1982, as Begin’s defense minister, he efficiently oversaw Israel’s uprooting of the Sinai settlements as part of the Israeli commitments in the Israel-Egypt peace treaty.

But 1982 was decisive to Sharon’s political career in another way. He planned and then carried out Israel’s invasion of southern Lebanon, culminating in the siege of Beirut and eviction of the Palestine Liberation Organization from Lebanon—and the massacre, by Lebanese Christian militiamen, of several hundred Palestinians in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila. Sharon was held partially responsible for the massacre by an Israeli commission of inquiry and ousted from the defense ministry and was demonized by both the press and the public in the West, as well as by many Israelis.

Nevertheless, through the 1980s and 1990s, Sharon inched his way back into political respectability. By 2001, when he was elected prime minister at the head of the Likud, he had recast his image, emerging as a responsible elder statesman with a security-defense background that most Israelis could trust. Like the ex-Gen. Yitzhak Rabin, with whom Sharon enjoyed very good relations through the decades, here was a man who could—cautiously—advance toward peace but also be depended upon to safeguard Israeli security. His appearance—a smiling, overweight, white-haired teddy bear, a man who was photographed with his sheep—certainly helped. So did the occasional leaks by former aides and secretaries about his abundant sense of humor, warmth, and many personal kindnesses.

***

From the moment he assumed the premiership, in 2001, Sharon showed the promise of political greatness. Starting in 2002, he orchestrated the Israeli military’s efficient suppression of the Palestinian Second Intifada—a rebellion against Israel’s occupation of the territories, but also a terrorist war against Israel itself, that began in September 2000. And he did this at a relatively low cost in terms of Arab civilian life—most Israelis killed in the Second Intifada were civilians, but most Arabs killed in the Second Intifada were gunmen.

But Sharon then proceeded—somewhat belatedly, left-wingers would say—to veer toward conciliation, apparently under the influence of the Intifada and out of recognition that continued Israeli rule over the West Bank and Gaza Strip would, inexorably, lead to the emergence of a single state with an Arab majority between the Jordan and the Mediterranean, an outcome that would necessarily spell an end to the Zionist dream of a democratic Jewish state.

In the summer of 2005, he orchestrated the unilateral Israeli withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, which meant not just the pullout of all troops but also the politically challenging and psychologically traumatic uprooting of a dozen or so Jewish settlements. (Four settlements from the northern West Bank were evacuated besides.) Sharon abruptly lost his Likud base of support—so in November that year, while still prime minister, he set up a new centrist political party, Kadima. Most observers, and his rightist opponents, believed that Sharon intended, in the absence of a peace agreement with the Palestinians, to affect a complete separation from the Palestinians by unilaterally withdrawing from the bulk of the West Bank as well.

Sharon grew up with an instinctive, essential distrust of his Arab neighbors in Kfar Malal; after all, in 1921, a few years before Sharon was born, they burned the moshav to the ground. As an adult, Sharon gradually extended this distrust to encompass “the Arabs” in general. Indeed, in 1978, he voted in Cabinet against the evolving Israel-Egypt peace agreement negotiated between Prime Minister Menachem Begin—aided by ex-generals Moshe Dayan and Ezer Weizmann—and President Anwar Sadat. (In the decisive vote, in the Knesset in 1979, Sharon voted “aye.”) And in the early 2000s he had had little hope that the Palestinian Arabs under Yasser Arafat, and then Mahmoud Abbas, would ever acquiesce in Israel’s existence or sign a definitive peace treaty with the Jewish state.

So, as part of his “separation” policy, he proceeded to build a security fence between “old” Israel—that is, pre-1967 Israel—and the West Bank. Such a pullback to the fence would have left the Palestinians in possession of about 90 percent of the West Bank—though it also would have left the problem of dozens of Israeli settlements “stranded” inside Palestinian territory. It is unclear how Sharon intended to deal with this or how he thought he would overcome the inevitable resistance of the right wing. In any event, his stroke put paid to this possibility.

When Sharon disappeared from the political arena, in January 2006, both Palestinian and Jewish extremists rejoiced. But there was a real sense of shock, sadness, and loss among most Israelis, who felt—probably correctly—that the only political figure willing and able to extricate—liberate—Israel from the West Bank and thus able to change the course of the country’s history, was gone. His actual passing, after eight years in a coma, is anti-climactic. What comes next, for Israelis and Arabs—and for everyone else, including the Americans—is anyone’s guess.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Benny Morris is a professor of history at Ben-Gurion University and the author, most recently, of One State, Two States.

Benny Morris is an Israeli historian and the author, most recently, of Sidney Reilly: Master Spy (Yale 2022).