Forget Peanuts and Cracker Jack. What Jews Love About Baseball Is Jewish Players.

A new exhibit paints the sport as a vehicle for assimilation, but Greenberg, Koufax, and even Ryan Braun are Jewish role models

It takes something less than an advanced Sabermetrician to confirm that, yes, Jews are underrepresented at the highest echelon of major professional athletics. Sports broadcasters? We can do that. Sports agents? In abundance. Sports commissioners? Currently the men atop three of the “Big Four” leagues are Jewish. Owners? Absolutely: During my youth in the Midwest, the owners of the five nearest NBA franchises had the surnames Simon, Gilbert, Davidson, Reinsdorf, and Kohl.

Players? Not so much.

I would submit that, as a rule, we’re comfortable with the modest roster of Jews in uniform. As the contemporary athlete would say, “It is what it is.” In the NBA, the average height is 6-foot-7. How many congregants at your shul are within a standard deviation of that? In football, nature is double-teamed by nurture: Even if our sons had the physical dimensions to play professional football, would we want them tussling with the balagulas in the trenches, risking traumatic head injuries?

But our collective relationship with baseball is altogether different. The sport has become interwoven with the American Jewish experience. Several years ago Peter Miller, a Ken Burns protégé, directed a documentary titled Jews and Baseball: An American Love Story. The title was hardly an overstatement—there is, after all, a Baseball Talmud; suffice to say, there is no Hockey Haggadah.

The Jewish romance with baseball is thrown into particularly sharp relief at a new exhibit, “Chasing Dreams: Baseball & Becoming American,” which opens today at the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia. The show explores the thesis that baseball occupies such a prominent position in the American-Jewish psyche because, for so many, it lubricated the engine of assimilation and represented a means for the marginalized to enter the mainstream. The famous observation of cultural historian Jacques Barzun echoes throughout: “Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball, the rules, and reality of the game.” So does the Philip Roth essay published by the New York Times on Opening Day in 1973, which argues, “Baseball was a kind of secular church that reached into every class and region of the nation and bound millions upon millions of us together. … Baseball made me understand what patriotism was about, at its best.”

Inadvertently, though, the exhibit offers a much simpler, and more convincing, explanation for American Jewry’s collective love affair with baseball: the presence—and at least occasional prominence—of Jewish ballplayers. Scan the exhibit and it becomes clear that virtually every era in baseball has produced at least one Jewish star whom Jewish children could look up to.

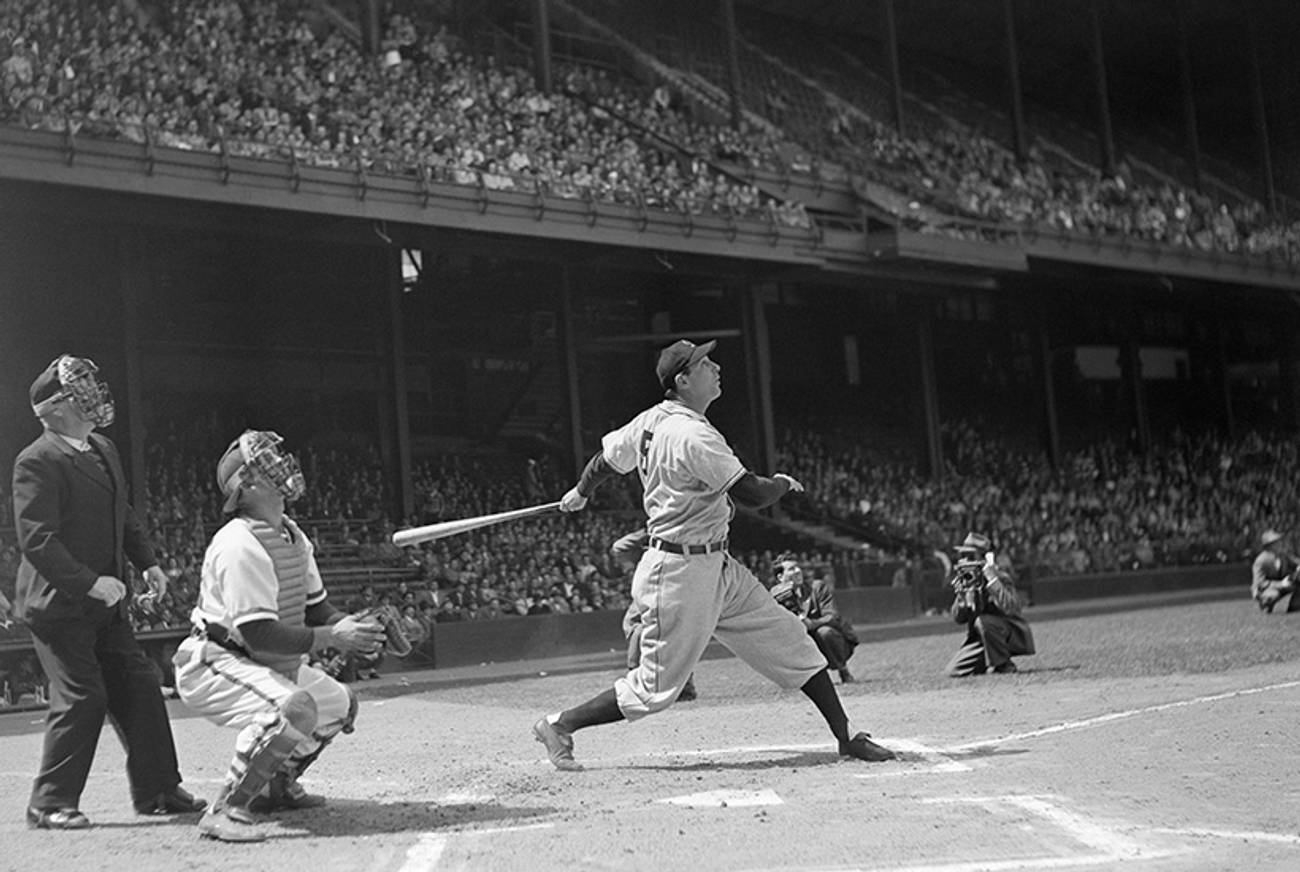

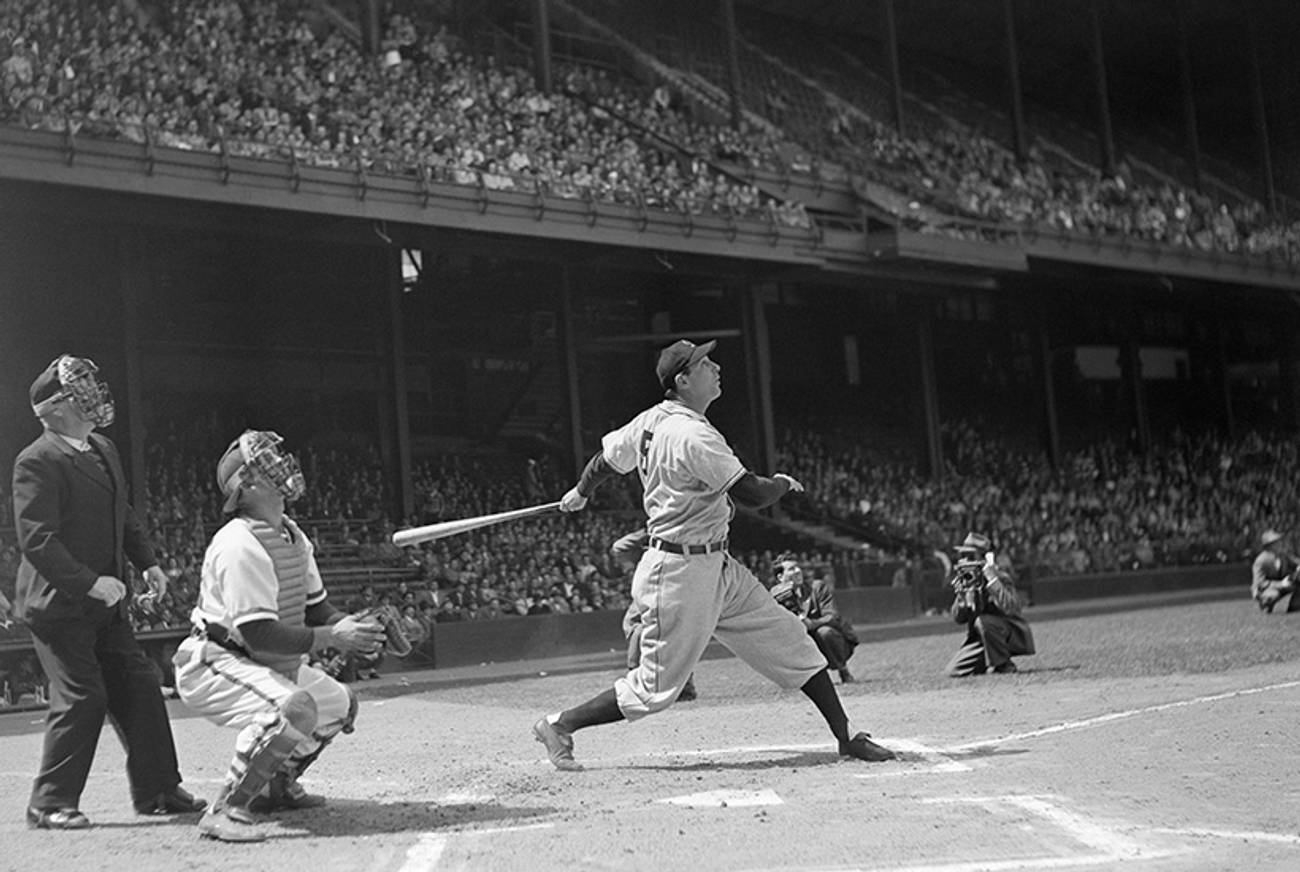

In fact, America’s first professional baseball player may have been Lipman Emanuel Pike—known as Lip—who pitched for the Philadelphia Athletics in the 1860s, drawing a salary of $20 a week. In the 1920s, the New York Giants produced Moe Solomon, “The Rabbi of Swat,” their answer to the Yankees’ Babe Ruth. A decade later, the Giants had Harry “the Horse” Danning, a four-time All-Star. At the same time, the Detroit Tigers had the great slugger Hank Greenberg, who, in 1934, became the first Jewish player to attract attention for his decision to sit out a World Series game on Yom Kippur—at his mother’s behest. (He got a standing ovation that day, as he walked into Detroit’s Congregation Shaarey Zedek.) The tradition eventually includes Sandy Koufax’s refusal to pitch the 1965 World Series on Yom Kippur, the cardinal American Jews-in-sports story. (It helped that he came back to win the decisive game.)

These days, Kevin Youkilis, a three-time All-Star, helped the Boston Red Sox break their famed World Series curse. Infielder Ian Kinsler, currently with the Tigers, is a three-time All-Star. Milwaukee’s Ryan Braun—nicknamed, inevitably, the “Hebrew Hammer,” though the vote here was for the “He-Brewer”—was the National League Rookie of the Year in 2007 and the MVP in 2011.

So, Jews got game. Sure, it’s all relative: The 170 or so Jews to have played in the Big Leagues comprise roughly 1 percent of the MLB alumni. And truth be told, we tend to bend the rules to make the Jewish roster as large as possible. The Cleveland Indians’ Hall of Fame shortstop Lou Boudreau wasn’t raised Jewish—he was adopted by a Christian family—and never identified as Jewish. But his mother was Jewish, so technically he counts. On the other side is the virtuosic Minnesota Twins hitter Rod Carew, who was lionized in Adam Sandler’s “Chanukah Song”: “O.J. Simpson, not a Jew /But guess who is? /Hall of Famer Rod Carew—he converted!” Carew never, in fact, converted—but he was married to a Jewish woman, raised his children Jewish, and wore a chai on a necklace as he won batting titles as a matter of ritual. Close enough.

David Eckstein and Mike Mordecai are both non-Jews but have been informally adopted simply by dint of their Jewish-sounding surnames. When David Cone started playing for the New York Mets in 1987, he was so flooded with bar mitzvah invitations that the team PR man, Jay Horwitz, felt compelled to issue a statement breaking the regrettable news that Cone was not in fact Jewish. (Better that than the Florida Marlins, which held a Jewish Heritage Day in 2006 honoring their first-baseman, Mike Jacobs—who is not Jewish, as the team’s marketing wizzes later learned. Oy.)

But there are players who have gone out of their way to embrace their Jewish roots, perhaps because they recognize that Jewish bona fides make for a great way to expand their constituency of admirers. Gabe Kapler, a much-traveled outfielder, emblazoned a Star of David tattoo on his left calf; on his right, he has the phrase “Never Again” with a flame and the dates of the Holocaust. Shawn Green, a stellar player of the 1990s and 2000s, never had a bar mitzvah growing up but, as a Major Leaguer, followed in the tradition of sitting out a World Series game that coincided with Yom Kippur. His money quote: “I thought it was the right example to set for Jewish kids, a lot of whom don’t like to go to synagogue.”

The downside of looking up to Jewish players, though, is that it leaves Jewish fans exposed to much greater disappointment when they fall. In 2011, Ryan Braun tested positive for elevated levels of testosterone, a telltale sign of performance-enhancing drugs. He appealed the test and wasn’t punished but last season was implicated again after records from Biogenesis, a south Florida “anti-aging clinic,” indicated that Braun had been receiving banned performance-enhancing drugs. This time he pleaded guilty and missed the last 65 games of the 2013 season, forfeiting more than $3 million in salary.

What a shanda, my father-in-law lamented when he learned about Braun, beset by the same sinking feeling that afflicted him when he learned that Bernie Madoff was Jewish. But now Braun has embarked on the celebrity rinse cycle: He disappeared for a few months, letting the scandal run its course. He arrived at Spring Training last month and held a press conference, asserting, “All I can do is look forward and continue to move forward.” There will be penance. There will be forgiveness—the speed of which will move in lockstep with Braun’s on-field performance—and ultimately, there will be redemption. What could be more American than that?

Jon Wertheim is executive editor of Sports Illustrated. His Twitter feed is @jon_wertheim.