Welcoming Myself Back to My Journalistic Roots

I got my start in a contentious corner of the Jewish press. It’s good to be here again.

GREETINGS, GENOSSEN!

The editors of Tablet have generously invited me to fill a few inches of their electronic space on a regular basis with ruminations, fulminations, and reports, according to my inclination. Please allow me, by way of introduction, to use the first of those inches to display my Jewish journalistic qualifications, as if pointing to my diplomas. These are not in every field. On sacred and theological matters, I am an illiterate peasant. Some of the finest of journalists are Talmudists, as the readers of Tablet have reason to know, and I am not among them. Still, I claim one distinguished credential.

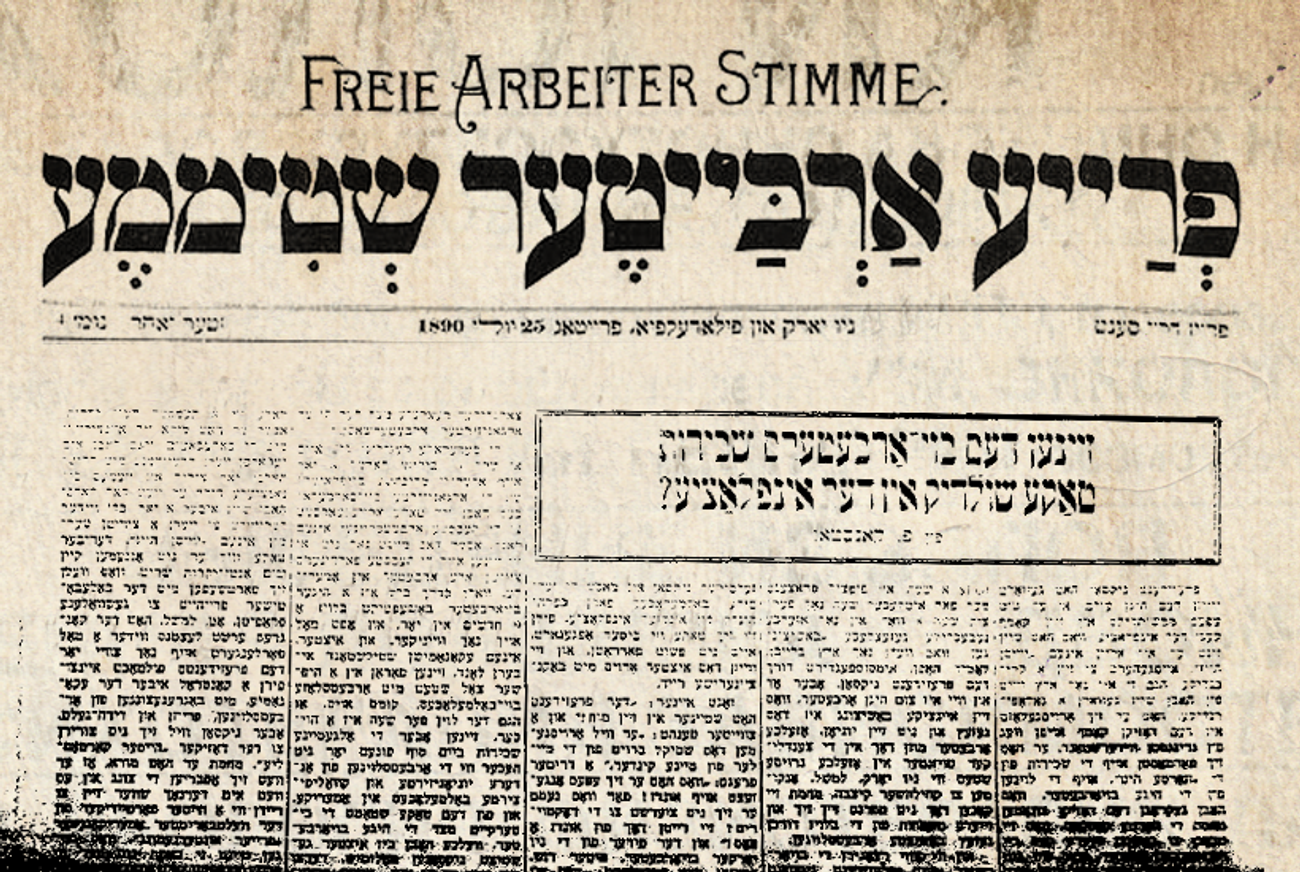

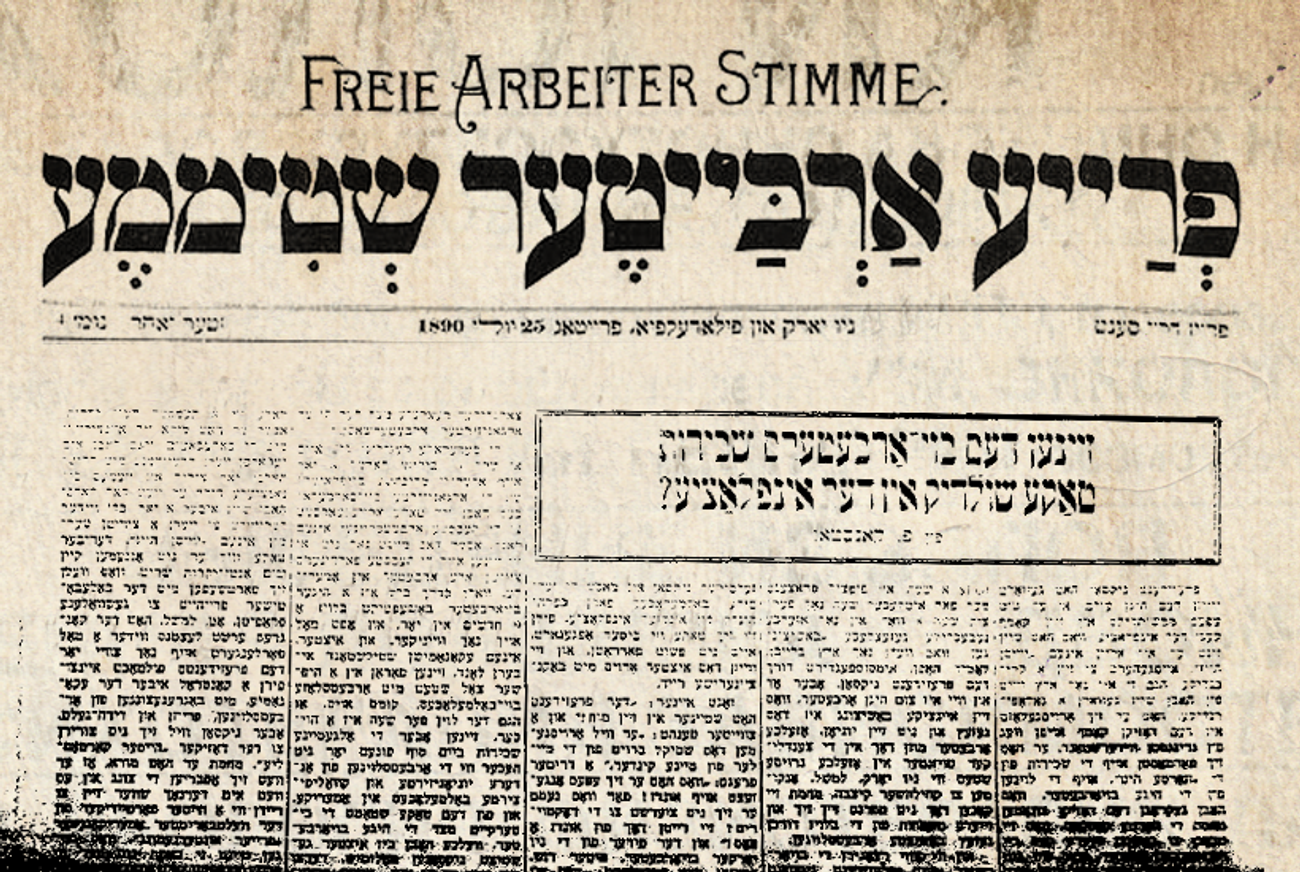

The first professional journalist to take a benign and extended interest in my writings was the editor-in-chief and jack-of-all-trades of the august Yiddish newspaper the Freie Arbeiter Stimme, which, given the chaos among Yiddishists, is sometimes transliterated as Di Fraye Arbeter Shtime but is always translated as the Free Voice of Labor. The estimable Stimme was founded in 1890 on the Lower East Side, and a fin-de-siècle breeze wafted through its columns ever after. The newspaper in its early days was the organ of the Pioneers of Liberty, who gave way to the Jewish Anarchist Federation, which considered itself the acme of the American labor movement. And, in time, the paper prospered.

The 1910s and ’20s were its golden age. The 1930s weren’t bad, either. Di Yunge published poetry in its pages. By the 1970s, the golden age had faded away, along with all the other ages, and yet the paper soldiered on, with a little help from the garment unions. The final editor was Ahrne Thorne, pen name P. Constan, who was obliged to oversee the official demise, a dismal task, in 1977. Even so, Ahrne, ever optimistic, remained on the lookout for new contributors, and, during the feeble last year or two of the paper’s existence, he came up with me, which makes me probably the last new writer to have been discovered by the ancient Freie Arbeiter Stimme.

I was not an altogether legitimate discovery. Ahrne translated my English-language contributions into a Yiddish that I do not speak, though he presented me to the readers as a new Yiddish writer. I was a fake, then. He counted on my discretion. I also suspected that, in the course of translating my articles, he improved them. A Yiddish-speaking friend once congratulated me for having written a militant protest against fascism in Spain, which concluded, “Free the political prisoners from Spanish jails!” To my shame, I had never written such a sentence. I reproached Ahrne for tinkering with my copy. He denied doing any such thing.

But I do not bear a grudge. The Freie Arbeiter Stimme stood for the grandest principles of the oldtime labor left—anti-fascist, it goes without saying, and, on social-justice grounds, anti-communist, as well. (Ahrne lectured me on this point.) The paper was keen for a peculiar kind of socialism, conceived on libertarian lines. It was also appreciative of America, in spite of grievous faults, and appreciative even of American power abroad, when deployed for noble purposes, which does happen. Does the mix of 1890s labor anarchism and 20th-century Cold War liberalism seem a little odd? I see a charm in it, and even a logic.

I proclaim my satisfaction at returning to my journalistic roots. I hope the readers of Tablet will understand that, having gotten my start in a contentious corner of the Jewish press of long ago, I have no alternative but to go on thumping the table here. The readers may sometimes puzzle over my reasoning, but they will know what I think. And I hereby dedicate every word of my forthcoming Tablet contributions to the memory of Ahrne Thorne, originally of Lodz, compositor by day at the daily Forverts, editor by night of the Freie Arbeiter Stimme, and champion night and day of Jewish culture and universal ideals.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.