Two Iranian truck drivers sat idly in the parking area of the Poti Free Industrial Zone (FIZ), waiting for customs authorities to clear their cargo and for FIZ personnel to prepare new papers. Within hours, they’d be chugging along Georgian roads on their way to Iran. Three more Turkish trucks awaited just outside the FIZ entrance, while a dozen containers lay between the customs office and the FIZ’s only warehouse.

A friendly manager of RAKIA Georgia, the FIZ’s owner, welcomed me on a warm late October afternoon after a seven-hour drive from Georgia’s charming capital Tbilisi. My hostess solicitously whisked me to a conference room, fetched me a strong Georgian coffee, pointed to the restrooms, and promised she would join me in a few minutes. Left alone, I looked around. Strewn over the large mahogany table was informational material left from a previous meeting. Alongside some glossy promotional brochures was a thick A4 document, a summary of the Free Zone’s investment strategies from 2010 to 2013.

Iranian trucks parked by the entrance of Poti Free Zone, Oct. 23, 2014. (Photo: Emanuele Ottolenghi)

Poti FIZ obtained its 99-year concession over 300 hectares of land adjacent to Georgia’s largest container terminal on the Black Sea in 2008 and began operations two years later. The FIZ offers attractive tax advantages to its companies, as long as the ultimate destination for their merchandise is outside Georgia.

Elsewhere, in June 2013, the Wall Street Journal exposed Iran’s sanctions evasion in Georgia. The Journal reported that:

The business branch of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps has some 150 front companies in Georgia for the purpose of evading sanctions and importing dual-use technology, according to two members of the Revolutionary Guard and to the head of a Tbilisi facilitator agency—who said he helped set up such firms registered under Georgians’ names.

The Journal’s story also focused on Houshang Farsoudeh, Houshang Hosseinpour, and Pourya Nayebi—three Dubai-based Iranian businessmen. On Feb. 6, 2014, the U.S. Department of Treasury sanctioned them and eight of their businesses, including two registered at the FIZ. Treasury designated them under Executive Order 13608, “which targets foreign persons engaged in activities intended to evade U.S. economic and financial sanctions with respect to Iran and Syria.” According to Treasury:

These three individuals have established companies and financial institutions in multiple countries and have used these companies to facilitate deceptive transactions for or on behalf of persons subject to U.S. sanctions concerning Iran. In 2011, they acquired the majority shares in a licensed Georgian bank with direct correspondent ties to other international financial institutions through a Lichtenstein-based foundation they control. They then used the Georgian bank to facilitate transactions worth the equivalent of tens of millions of U.S. dollars for multiple designated Iranian banks, including Bank Melli, Mir Business Bank, Bank Saderat, and Bank Tejarat.

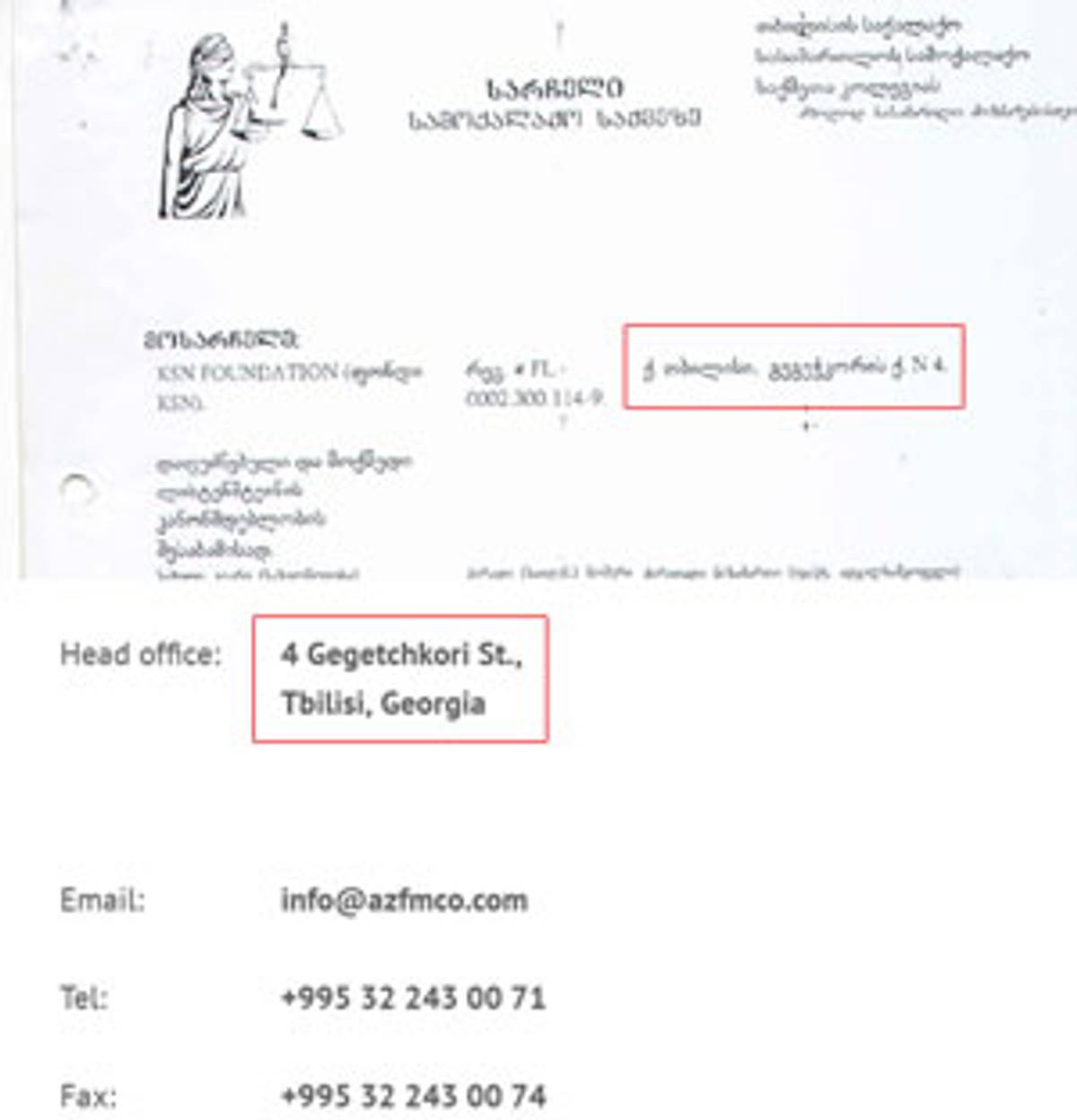

Treasury was referring to Investbank JSC and the Lichtenstein-based KSN Foundation, which it designated. The complex corporate architecture Treasury mentioned spanned the globe, including a company in Panama, three in New Zealand, one in Switzerland, and dozens spread between Dubai, Poti, and Tbilisi.

For anyone familiar with their activities, the span of companies and fields of endeavor was impressive. The three Iranian businessmen had been on an investing spree, launching the private airline Fly Georgia, trying (unsuccessfully) to buy Tbilisi’s Sheraton Metekhi Palace hotel, and creating local companies involved in real estate, investment, holiday packages for Iranian tourists, aviation services, microfinance, currency trade, and prepaid credit cards. Although many of these companies were not targeted by Treasury sanctions, Georgian authorities went after them. According to MoneyLaundering.Com’s Kira Zalan, “Georgian prosecutors subsequently obtained a court order to freeze Nayebi’s assets, as well as the accounts of 18 companies and 16 individuals associated with the scheme.” Court records mention Farsoudeh, Hosseinpour, their business associates, and relatives or companies they run, including companies not targeted by Treasury.

Image from the now no-longer existent Facebook page of Fly Georgia: Houshang Hosseinpour (second from left), his daughter Tannaz (center), and Pourya Nayebi (second from right) at a Fly Georgia corporate event, April 2013. (Courtesy Emanuele Ottolenghi)

I knew that the Iranian trio had hired some of their relatives to run their activities in Georgia: Hosseinpour’s daughter Tannaz, aka Fatemeh (whose company, THP Global, is cited in court papers) worked as media-relations director for Fly Georgia. Other family members mentioned by the court include Nayebi’s two sisters, one of Nayebi’s brothers-in-law, Ali Abbasi, who held a managerial position in the airline, and Nayebi’s wife, Nina Navisa, who helped promote it. Another brother-in-law worked at “New York Exchange”—a money exchange business with branches in Tbilisi, Dubai, Delaware, and Toronto. (The Toronto branch’s registered address was a residential property owned by Hosseinpour’s wife.) New York Exchange is one of the companies Treasury designated for having “deceived the international financial community, including by generating false invoices in connection with transactions involving designated Iranian banks.”

The Iranian trio and their associates had elected to incorporate some of their businesses in Poti. I was curious to see whether they were still active; whether there was more Iranian traffic going through the free zone and if so, of what kind. I was also trying to figure out what had happened to the three Iranians and their associates. Had they abandoned ship and retreated in defeat? Were the 150 IRGC companies mentioned by the Wall Street Journal still active? What about Iran? Were the sanctioned companies a part of a larger Georgia sanctions-evasion channel? Or was all of this activity simply innocent, legal commerce?

A small, emerging economy that is still mostly agricultural, Georgia is a far cry from Turkey and Dubai—both places notoriously favored by Iranian proxies for sanctions evasion. Yet Georgia’s modest economy is precisely what attracts Iran’s middlemen: The country is close, its economy is cash-driven, and sophisticated customs and border-control technology is too costly to be deployed at every checkpoint. As Iranian proxies have found themselves increasingly squeezed out of Europe, they have moved their complex networks in Iran’s “near abroad,” where they can expand undetected in the cat-and-mouse game they play with Western sanctions-enforcement officials.

The most notorious documented case of Iran’s sanctions evasion involved Babak Zanjani, an Iranian middleman whom the European Union blacklisted, along with his companies, in December 2012, followed shortly thereafter by a U.S. Treasury designation in April 2013. Zanjani initially denied any involvement but then later publicly prided himself on his actions to elude sanctions through a network that spanned Turkey, Tajikistan, and Malaysia. Zanjani, who until 2010 was a virtual unknown, built a business empire in less than three years. The linchpin of his operation was a small bank in the Tajik capital Dushanbe, which E.U. and U.S. officials believed he used as a conduit for illicit financial transactions on behalf of Iran. Farsoudeh, Hosseinpour, and Nayebi stood accused of using a similar bank scheme elsewhere.

When European Union sanctions hit Zanjani in December 2012, he started divesting himself of legal ownership of his web of corporate entities. By the time U.S. sanctions hit him, most of his assets had changed hands. Zanjani also had the misfortune of taking the wrong side inside Iran’s regime and may have been used as a scapegoat by President Hassan Rouhani’s new administration—he was arrested in December 2013 and remains in prison under unspecified charges. Georgian corporate filings show that the three Iranians, on the other hand, remained active in Tbilisi after Treasury’s actions against them. I was determined to find out if they had done the same as Zanjani.

In Georgia, after all, things may have turned out better for Iran’s agents of sanctions evasion. In 2010, Tbilisi and Tehran agreed to a visa-free regime to facilitate bilateral tourism and business. Coming at the same time as tough new U.S. and European autonomous sanctions on Tehran, the move allowed thousands of Iranians to flock to Tbilisi for business or to the Black Sea resort of Batumi for pleasure. It also created a new channel for middlemen suddenly cut off from Europe to find ways to circumvent sanctions. Clearly, not all Iranian businesses opened in Georgia since 2010 sought to service the sanctions-evasion needs of the regime in Tehran, but some did, including companies owned by Farsoudeh, Hosseinpour, and Nayebi.

Eventually, Georgian authorities cracked down on Iranian suspicious activities and, in June 2013, unilaterally revoked the visa-free regime, froze 150 bank accounts of Iranian nationals and Iranian-owned companies, and put Investbank under the country’s central bank’s supervised management. As FIZ officials told me, many of those companies were registered at the Free Zone, and once their bank accounts were frozen, they were forcibly shut down due to their inability to conduct payments. It sounded like the Iranians were gone.

The Georgians clearly displayed zeal in their solicitude to American entreaties; yet the policy was something of a hit-or-miss. Two Tbilisi-based Iranians, who agreed to speak to me on condition of anonymity, both had their former banks abruptly close their accounts in June 2013. Neither had any discernible role in sanctions-evasion activities—though one had offered his services as translator or helped incorporate hundreds of Iranian companies, including those of the three sanctioned Iranians. It seemed that Tbilisi took no chances.

With Georgian authorities breathing down their necks, the three Iranian businessmen scrambled to sell their 70-percent stake in Investbank just in the nick of time. Two weeks before the visa-free regime was revoked, they signed a deal with a Georgian lawyer who became the custodian of their shares and was entrusted to sell them on behalf of KSN Foundation, the official owner. The moves may or may not have been an effort to avoid sanctions, but before they could sell, their assets were frozen. Shortly after, one of Fly Georgia’s planes was impounded for the company’s failure to pay leasing charges. The airline abruptly stopped operations.

It looked as if Treasury’s actions (and prior visits to Tbilisi through 2012 and 2013) constituted a textbook case in the success of the U.S. sanctions policy. By making a compelling case to a foreign ally through Treasury’s painstaking forensic work, the Obama Administration had neutralized an important illicit Iranian operation there and potentially damaged others. Yet in fact the Treasury designation encapsulates sanctions’ main challenge. Enforcing them requires tedious bookkeeping, painstaking forensic work, and the ability to stay a step ahead of Iranian middlemen with three decades of experience circumventing embargoes. These difficulties, which are painfully obvious on the ground, suggest that President Barack Obama’s faith in “snap-back sanctions” that will penalize Iran if it violates the terms of any nuclear deal take little account of how sanctions actually work on the ground.

Sanction laws are written in Western legalese, requiring an army of enforcers—both human and machine. Intel agencies, export-control authorities, customs, law-enforcement agencies, port authorities, and border guards must be both vigilant and competent. The business community too needs legions of anti-money-laundering and compliance officers, lawyers, and experts to navigate the system. It takes repeated trips to persuade foreign governments to comply with sanctions. Some share our policy goals. Some don’t. The further down the chain one goes the less compelling the argument for helping the United States enforce sanctions. For underpaid customs officials in far-away countries like Georgia, it comes down to the choice between the thankless task of doing the Americans a favor and the marginally riskier but potentially more profitable option of letting the Iranians go.

Enforcing sanctions requires tedious bookkeeping, painstaking forensic work, and the ability to stay a step ahead of Iranian middlemen with three decades of experience circumventing embargoes.

Treasury took two years to discover, investigate, corroborate, and finally sanction the people they eventually designated as Iran’s proxies in Georgia. Even so, Treasury targeted only eight of the 18 businesses mentioned in Georgian court proceedings. It is, of course, entirely possible that only those eight companies engaged in sanctionable activities, while all others were honest businesses. However, the pending Georgian court case against more of their companies, relatives, and business partners suggests a possible alternative explanation. It is also plausible that Treasury could not gather sufficient evidence against those companies or that it failed to identify them. If that were the case, it would expose the constraints of an effective sanctions policy.

Treasury’s actions against the Iranian trio happened at the height of the sanctions regime, when compliance with U.S. sanctions among financial institutions, global businesses, and foreign governments was at its zenith. It will be much harder in a post-sanctions environment. My colleagues Mark Dubowitz and Reuel Marc Gerecht contend that “the president’s much-hyped ‘snap-back’ economic sanctions, now the only coercive instrument Mr. Obama has against Iranian noncompliance, will also surely fall victim to the Security Council’s politics and human greed.” What the Treasury has called Iran’s evasive action could then start over again, at even higher stakes.

In Georgia, there are signs that it may already have. Commercial registry documents show that the trio incorporated some of their companies registered at Poti FIZ. Pourya Nayebi is listed as either owner, manager, or holding power of attorney over Georgian International Shipping, Georgia Business Development FIZ LLC, and Poti Free Zone Business Authority, among others. For his part, Houshang Hosseinpour owned Fly Georgia FIZ LLC. Georgia Business Development was sanctioned by Treasury. Fly Georgia FIZ LLC, Georgia International Shipping, and Poti Free Zone Business Authority are mentioned in the money-laundering case pending in the Tbilisi city court. At a meeting with two of RAKIA Georgia’s senior executives in Tbilisi in late October, my interlocutors confirmed that they had negotiated the sale of the Sheraton in Tbilisi with the three Iranians, but that the latter had incurred payment difficulties and the deal had fallen through. My hosts—who later arranged my security clearance to visit the Free Zone—inquired with concern about Iran’s nuclear program and regretted the inconvenience caused by their former customers.

So, there I was, staring at an internal strategy paper, complete with statistics showing that the closure of 90 companies since late 2013 due to banking irregularities has not deterred Iranian investors. By their own numbers, of 256 companies registered in the FIZ since 2010, 166 are still active and 84 belonged to Iranian nationals. Adding all other companies owned by Iranians using a different passport and jurisdiction, about two-thirds of companies incorporated in the Poti FIZ have links to Iranians, including business partners of the three businessmen sanctioned last year, together with a number of legitimate enterprises.

The FIZ has no responsibility for what companies do. Still, the Free Zone actively courted Iranian business throughout its existence, despite U.N., U.S., and E.U. sanctions in place against Iran since 2007. Iran constituted a target of expansion since the very beginning. According to a January 2009 embassy cable leaked by Wikileaks, the director “underscored the role of Iran as a potential destination for or initiator of cargo. He … assured the DCM that [his company], though looking for investors, does not plan to invite Iranian investment in actual port ownership, preferring to transit Iranian cargo.”

At the height of the rial devaluation crisis in 2012, the FIZ offered discounts to Iranians seeking to start companies. Until August 2013, well after E.U., U.N., and U.S. sanctions were introduced, RAKIA Georgia had a full-time representative in the Islamic Republic named Sassan Lessan, aka Sassan Corben (FIZ officials say he is no longer employed, and a request for comment went unanswered). It also advertised letters of credit and money-transfer services to and from Iran, despite U.S. and E.U. banking sanctions against most Iranian banks, and as recently as March 2015, advertised on Iranian commercial websites. If the goal was to populate the Free Zone, with Iranian businesses, this strategy appears to have worked.

Poti FIZ has 166 businesses registered and active. On location, aside from the main RAKIA Georgia office building, an imposing gate, the customs-clearing platform, a warehouse owned by the FIZ, and four construction sites, the 300 hectares of coastal land are mostly untouched wilderness. My interlocutor, who eventually reclaimed the internal document from me, conceded that most companies used the FIZ for transshipment purposes, could rent out warehouse space if needed, and could hire Free Zone personnel to handle paperwork.

It’s easy to see the appeal in all this. Transshipment allows companies to buy and instantly resell their merchandise to or from a third-party customer. To some extent, then, the transaction is fictitious. The profit is real, though, enhanced by the tax-free advantages offered. Free zones profit from the businesses they attract, and businesses benefit from a tax-free environment. Everyone prospers.

To those seeking to evade sanctions, free zones offer something else—a firewall of sorts in the paper trail linking transactions to sanctionable entities or merchandise. Though merchandise may station inside a free zone only for the few hours required to change its accompanying papers, when it departs, its place of origin is the zone itself. By allowing the repurposing of the origin of goods heading from Iran to the West and vice versa, a free zone can unwittingly help obfuscate the real entities engaged in a transaction. The Financial Action Task Force—a Paris-based international body tasked with advising governments on best practices against illicit finance—stated, in a 2010 memorandum on free trade zones and their vulnerabilities, that “Free trade zones (FTZs)”—comparable to FIZs—“present a unique money laundering and terrorist financing threat because of their special status within jurisdictions as areas where certain administrative and oversight procedures are reduced or eliminated in order to boost economic growth through trade.” When it can be found, relaxed oversight, insufficient transparency, money laundering, and illicit traffic are the ideal environment for Iranian sanctions evasion.

It’s possible that Iranians came to Poti because they knew the benefits of free zones after exploiting them for years in the United Arab Emirates. Western companies habitually refrain from selling to or buying from Iranian counterparts, but they might have fewer scruples about transacting with businesses with Western-sounding names that are incorporated in a free zone outside Iran. Service industries around Poti also help ensure smooth operations. These include Farsi-speaking business-incorporation services in Batumi, where Iran has a consulate just in case. Consulting firms that promote Iranian investment in Georgia are also for hire, as well as virtual-office services and legal assistance. The FIZ does the rest for a fee, including renting warehouse space in the only storage facility so far available. There are even services for those seeking second citizenship or permanent residency in a European or North American jurisdiction—after all, dual nationals can produce a non-Iranian passport when they cross borders, meet bank managers, or inquire about dual-use technology. That may be the reason nine Iranians registered their businesses at the FIZ using passports from St. Kitts and Nevis.

Tannaz Hosseinpour’s passport and boarding pass on 11 March 2013. (Via Twitter)

I knew that Iranians favored the island nation’s passport thanks to Hosseinpour’s daughter, Tannaz. Until 2013 an undergraduate at George Washington University, she used to jet-set between Washington, D.C., Toronto, Dubai, and Tbilisi. On one of her trips, she posted a photograph of her boarding card and St. Kitts and Nevis passport on her Twitter feed. (On May 16, 2015, she Tweeted she was wiping her account of all earlier entries: “Tannaz Hp [@Tannazi] 5/16/15, 12:18 Deleting twenty four months of memories.”)

In Georgia, I found many other Iranian expatriates using a St. Kitts passport to register their businesses. The Caribbean nation’s passport is easy to obtain. St. Kitts citizenship regulations remain among the most lax in the world: No residency is required, and a passport is provided within three months in exchange for $250,000 or a qualifying investment in real estate. Though once hidden from view, Iranian exploitation of citizenship-for-investment schemes is becoming something of an open secret, partly because since sanctions against Iran began to bite, Iranian requests for citizenship have poured in. In 2011 SKN barred Iranians living in the Islamic Republic from applying. Iranian expatriates, however, may still obtain SKN citizenship, and evidence suggests that Iranians who live abroad continue doing so in droves.

In May 2014 the U.S. Department of Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network issued an advisory “to alert financial institutions that certain foreign individuals are abusing the Citizenship-by-Investment program sponsored by the Federation of St. Kitts and Nevis (SKN) to obtain SKN passports for the purpose of engaging in illicit financial activity.” In December 2014, Treasury targeted another Iranian engaged in sanctions evasion, under Executive Order 13622, with a SKN passport.

Yet it is a common practice of Iranian sanctions evasion never to give up an asset easily. When, in 2007, U.N. sanctions and the U.S. Treasury came after Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL), the state-owned shipping company did not relent. Its English-language website vanished overnight, its European subsidiaries changed names and managers, and ships changed proprietors. Then those same ships changed flags and names, as my colleague Claudia Rosett has documented over the years. When Treasury finally designated the one thing a ship cannot change—its International Maritime Organization number—the Iranians once again adapted, dodging sanctions at sea by taking more tortuous routes. One of them may go through Georgia.

Conversations with Georgian authorities and Western officials familiar with the Invest Bank story yielded a familiar refrain: Iran’s bad business is gone. Hundreds of active Iranian companies suggest an alternative hypothesis—many Iranian businesses in Georgia still engage in activities suitable for sanctions evasion: prepaid credit cards, investment management and online trading, foreign exchange businesses, logistics and transport, shipping, real estate, and petrochemical import and export to name a few. Given these advantages, it might have been easier to adapt to U.S. sanctions than abandon ship. Even after Treasury’s hammer hit the three Iranians and the Georgians clamped down, the list of Iranians active in Georgia is a who’s who of the Iranian sanctions-evasion cottage industry. A search through Georgia’s registry of companies yields entries for representatives of Iranian companies sanctioned by the U.N., the U.S., and the E.U., including IRISL, the Supreme Leader’s business empire Setad Ejraye, the National Iran Tanker Company, and the shipping insurance club Kish P&I.

A developing economy with potential as a trade and energy corridor between East and West, Georgia is an ideal business magnet. But like its Armenian and Azeri neighbors, Georgia is a small nation squeezed between Russia, Turkey, and Iran—three competing powers with imperial pasts and appetites for hegemony. The South Caucasus has always been a land of conquest—the playground of empires, whose conquerors left imposing architectural landmarks and bloody memories behind. In their wake, there now rule small but proud countries who juggle between their aspiration for independence and the limits of their powers.

It may have been too optimistic to think that Georgia—a small country only a thousand miles from Tehran—would eradicate Iran from its business landscape. For Georgia, doing America’s bidding against the Islamic Republic was a bold move—and one that may have come with a price. Washington’s interest in the South Caucasus is fickle, its influence diminishing, and its appetite for muscle-flexing limited. The Armenians, locked in conflict with Turkey over history and with Azerbaijan over geography, have chosen to embrace Russia as a military patron and Iran as a commercial partner. Azerbaijan, with its energy resources, can afford a more independent policy. Georgia’s main potential is in the development of the ancient Silk Road connecting Europe to the East, which also depends on Russia—a fact that the Georgians learned the hard way in August 2008 when Russia invaded Abkhazia and South Ossetia, rolling its tanks within firing distance of Poti and just stopping short of Gori, Stalin’s birthplace 45 miles from Tbilisi. Georgians waited for the U.S. cavalry in vain. Since America’s friendship did not deliver either NATO membership or significant arms, signing a visa-free regime with Iran in 2010 may have been a way to hedge Georgia’s bets.

The money exchange business on Shota Rustaveli Avenue 20, March 2013 and October 2014. (Left photo: from the Facebook page of Saman Mellati, since removed; right: Emanuele Ottolenghi)

In Tbilisi, I walked past the addresses of the trio’s old businesses. It did not take long to see signs that they might be following a similar script. I knew what the U.S. sanctioned “New York Exchange” had looked like, thanks to one of its old employees’ Facebook photographs (now removed). The new business, called Georgia Exchange, looks almost identical—even the logo was uncannily similar.

Nor did it take long to uncover a handful of new businesses that appear to have at least some circumstantial links to Georgia Exchange. The company providing the money-exchange firm’s web design had also designed sites for Hosseinpour’s and Nayebi’s sanctioned companies. The former IT manager for the sanctioned New York Exchange, Orchidea Gulf Trading and other companies associated with Hosseinpour and Nayabi appeared to be the co-owner of the web designer and the registrant for its Internet domain. Georgia Exchange shares an IP address with New York General Trading, a Dubai-based U.S. sanctioned company linked to Hosseinpour and with Azeri Fund Management Company, which owns 75 percent of Georgia Exchange. Are these new incarnations of sanctioned entities? There is no trace of the Iranians in the commercial registry: Owners are all foreign nationals; listed managers are all Georgians.

Nevertheless, there is one element linking these new companies to the old sanctioned trio of Iranian businessmen. According to Kira Zalan, KSN Foundation, the Lichtenstein entity they created to control Invest Bank, is suing the new owner of the bank shares and the lawyer who sold them on KSN behalf, in a bid to regain ownership of the shares. KSN’s registered address in Tbilisi is the same address as that of Azeri Fund.

The first page of the lawsuit brought by KSN Foundation against Capital Bank JSC principal shareholder, showing Gegetchkori Street 4, the same as Azeri Fund’s website, as their registered address.

U.S. Treasury officials came and went, and Georgian authorities did what was requested of them. But the Iranians are determined to do business here. Their stakes are high: politically, for the regime, and financially, for those who do its bidding. Periodically, they get caught and sometimes arrested. But mostly they muddle through, sometimes scoring big successes. Most important, sanctions have forced them to adapt, regroup, and become more inventive. The regime is generous with those who serve it: high commissions for those who succeed; top legal assistance for those caught.

Unless sanctions enforcement is relentless, Western successes rarely translate into Iranian failures; just temporary setbacks. Now, with the tantalizing promise in sight of the end of sanctions, those who for years took risks to help the regime (and become very rich in the process) will be hailed as heroes—patriots who helped Iran weather the storm and who now deserve preferential treatment in the post-sanctions economic climate. Possibly for that reason, Tannaz Hosseinpour declined to speak to me for this story.

“Due to a number of confidential reasons, I must respectfully decline your invitation,” she wrote. “Perhaps in a few months, the situation may be more suitable.”

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.