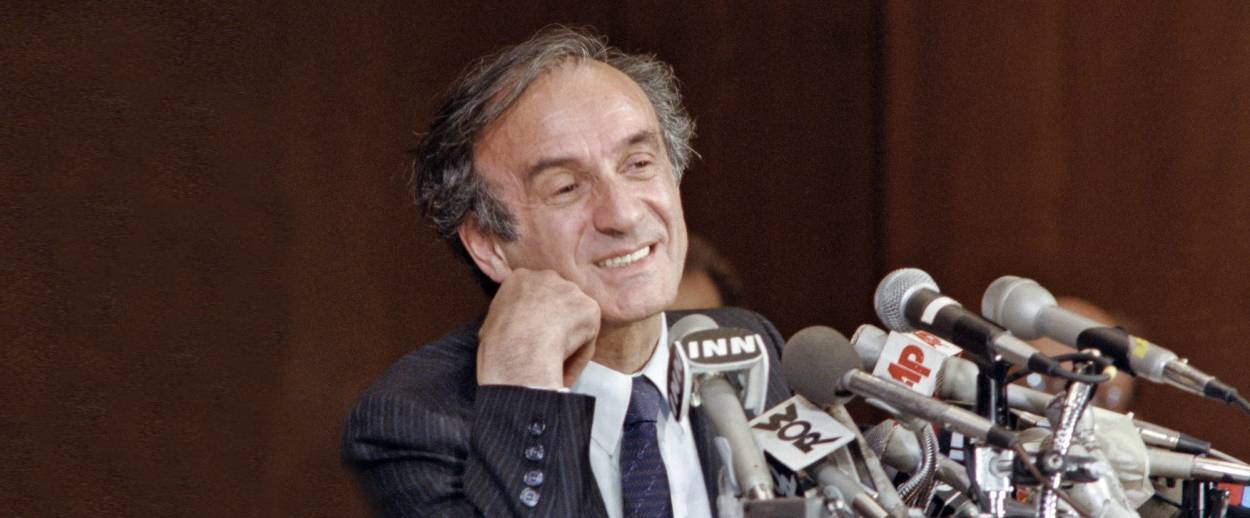

Remembering Elie Wiesel: A Tribute From a Friend and Disciple

The Holocaust survivor, Nobel laureate, author, activist, dead at 87

Elie Wiesel died Saturday at the age of 87. In the end, what remains with us, within us, most are the memories.

Much has been said and written, much remains to be said and written, about Elie Wiesel who, after emerging from the horrors of Auschwitz and Buchenwald, dedicated himself to perpetuating the memory of the millions of European Jews who were murdered in the Shoah. In doing so, he became the acknowledged voice of its survivors. He often said that he could not, would not speak on behalf of the dead. He did, however, speak forcefully, eloquently for the collectivity of the survivors, and they revered and loved him for it. “Accept the idea that you will never see what they have seen—and go on seeing now,” he wrote in his classic essay, “A Plea for the Survivors,” perhaps subconsciously opening a window into his own heart, “that you will never know the faces that haunt their nights, that you will never know the cries that rent their sleep. Accept the idea that you will never penetrate the cursed and spellbound universe they carry within themselves with unfailing loyalty.”

Not all survivors of the Shoah were able to transcend all they had experienced and witnessed in what Elie Wiesel famously referred to as the “Kingdom of Night.” Suffering, he once observed, “gives man no privileges; it all depends on what he does with it. If he uses his suffering against man, he betrays it; if he uses it to fight evil and humanize destiny, then he elevates it and elevates himself.” He described his own reflective existential crossroads in his lecture upon receiving the Nobel Peace Prize: “A recollection. The time: After the war. The place: Paris. A young man struggles to readjust to life. His mother, his father, his small sister are gone. He is alone. On the verge of despair. And yet he does not give up. On the contrary, he strives to find a place among the living. He acquires a new language. He makes a few friends who, like himself, believe that the memory of evil will serve as a shield against evil; that the memory of death will serve as a shield against death.”

There were so many dimensions to this unique, truly extraordinary individual. Elie Wiesel first came to public prominence, at the outset in France, then in the United States, in Israel and across the globe, as an author whose use of words was invariably elegant, direct, and piercing. The overriding common theme of his more than 50 books of both fiction and non-fiction is survival, not just the factual circumstance of survival but its transformative nature and, yes, power. The inmate of a Nazi death camp, the Soviet Jew struggling to retain a national and spiritual identity in the face of political oppression, the open-heart surgery patient, all are more than literary characters—they are alter egos with whom their author was in perpetual dialogue and through whom he taught and will continue to teach the reader the essential elements of overcoming whatever is most daunting, most harrowing, in one’s life. His memoir, Night, brought the horrors of the Holocaust into the consciousness of millions across the globe. His The Jews of Silence became one of the earliest rallying cries on behalf of Soviet Jewry.

Equally important was Elie Wiesel the teacher who made a lasting, often life-changing impact on thousands of students who sat in his classes first at New York’s City College, then at Boston University and Eckerd College, and most recently also at Chapman University. His lectures at the 92nd Street Y in Manhattan made the mysteries of Hasidism and Jewish biblical thought accessible to 20th– and 21st-century New Yorkers, Jews and non-Jews alike. He had an encyclopedic knowledge of literature and philosophy coupled with a seemingly inexhaustible intellectual curiosity. Nietzsche in particular fascinated him. At the same time, he was adamant in excoriating those who sought to exploit or trivialize the Holocaust. “Auschwitz,” he wrote, “signifies not only the failure of two thousand years of Christian civilization, but also the defeat of the intellect that wants to find a Meaning—with a capital M—in history. What Auschwitz embodied had none.”

Much has also been said and written, and much will surely continue to be said and written, about Elie Wiesel the man of conscience and human rights activist who urged one U.S. president publicly not to honor the memory of members of Hitler’s notorious Waffen-SS, and who implored another to put an end to the crimes against humanity being perpetrated in Bosnia. “That place,” Elie told President Reagan on April 19, 1985, referring to the Bitburg military cemetery in what was then West Germany, “is not your place. Your place is with the victims of the SS.” And he turned to President Clinton at the opening of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., on April 22, 1993, two years before the genocidal massacre at Srebrenica, and said: “And, Mr. President, I cannot not tell you something. I have been in the former Yugoslavia last fall. I cannot sleep since for what I have seen. As a Jew I am saying that we must do something to stop the bloodshed in that country! People fight each other and children die. Why? Something, anything must be done.”

But scholarly assessments of the life and career of the Hasidic boy from the Transylvanian town of Sighet who became a citizen of the world in the truest sense of that term will have to wait for another day. Mourning a friend is always personal, deeply personal, and today, I grapple with my memories of a friendship that spanned more than half a century.

I knew Elie from the time I was a teenager. He was a close friend of my parents, a frequent guest in our home. He and my father would sit for hours discussing the politics of the day and, far more than dwelling on their respective memories of Auschwitz-Birkenau and other Nazi camps, they would focus on the present-day challenges of remembrance and on improving the lot, both physical and spiritual, of their fellow survivors. One of my fondest memories of Elie is of him and my father singing Hasidic melodies, nigunim, their voices harmonizing as they took themselves back for a few minutes to the homes and families that had been torn from them. My favorite, perhaps also theirs: “She-yiboneh beis hamikdosh bi-m’heirah be’yameinu … May the Temple be rebuilt quickly, in our days …”

One evening at the beginning of my senior year of high school, he asked me, as he invariably did, what I was studying and how my classes were going. These were not perfunctory questions. He wanted detailed answers, especially about the books I was reading. I told him that the only class I did not enjoy was an advanced English seminar. I was frustrated by the teacher’s approach and his insistence on intellectually pigeonholing the assigned material. Elie was skeptical. He knew I liked, more than liked, literature. Perhaps, he said, I was subconsciously exaggerating. I showed him the most recent written assignment I had received back annotated with the teacher’s comments. Elie read it over, and said, “I see what you mean. You won’t learn anything that way.” He then offered to get together with me once a week to go over the readings with me, as well as my weekly papers. He was living at the Master Hotel on Riverside Drive and 103rd Street, and for the rest of that year, I went there to receive a weekly tutorial. We discussed in depth classical works of literature, and he patiently taught me how one translates thoughts into written sentences that take on a life of their own. “Write,” he inscribed a photograph of himself to me in French, “so that the words become a burning scar.”

June 6, 1972. Elie calls, his voice trembling with joy. He tells us that he and Marion have a son. Eight days later, my mother carries the child into the Wiesels’ living room on Central Park West to receive his name. Shlomo Elisha son of Eliezer son of Shlomo. Elisha’s birth transforms Elie profoundly, indelibly. For the first time in the more than 10 years that I’ve known him, he seems genuinely, thoroughly happy, content. Over the coming years, he is never happier, never more at ease than when he talks about Elisha and, in recent years, his grandchildren.

That same year, when he was appointed Distinguished Professor of Judaic Studies at New York’s City College and I was back in New York after graduating from Johns Hopkins, he asked me to be his teaching assistant. He taught a course on the literature of the Holocaust and a seminar on Hasidic thought. My tasks were to interact with the students on a regular basis, to grade papers, and to lecture about Elie’s own books, something he would not do. What struck me the most was how accessible he made himself to his students, especially the sons or daughters of survivors, who wanted to speak with him not about their studies but about themselves, their relationships with their parents, their efforts to understand what their parents had experienced. He would listen patiently, empathize, give advice. Perhaps more than anyone else, he was able to relate to the children and grandchildren of survivors. He not only understood us, but he empowered us to embrace our identity.

Soon after becoming chairman of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council in 1980, he asked me to organize and chair a Second Generation advisory committee. He wanted our input, to hear our perspective. “When I speak to others,” he said to us at the First International Conference of Children of Holocaust Survivors in May of 1984, “surely you know that I mean you, all the time. You are my audience, because it is you who matter. … Do you know what we see in you, in all of you? We see in you our heirs, our allies, our younger brothers and sisters. But in a strange way to all of us all of you are our children.”

June 1981. We are in Israel for the World Gathering of Holocaust survivors. Elie had been asked by the organizers to draft a Legacy of the Survivors for the occasion. He had written it in both French and Yiddish. In the lobby of the Hilton Hotel in Tel Aviv, Elie calls me over, gives me sheet of paper, and asks, “Have you seen the English translation of the legacy they prepared?” I told him I had not. After I finish reading the text he tells me that he finds it flat, prosaic. “Please write a new translation,” he asks me, adding, “I trust you.” It has always been a tremendous source of pride for me that when the Legacy was read in multiple languages during the closing ceremony at the Western Wall in Jerusalem, the English version was my translation of Elie’s text which he had approved.

January 1995. Elie is at Auschwitz-Birkenau. His words during the ceremony marking the 50th anniversary of that death camp’s liberation are searing: “In this place of darkness and malediction we can but stand in awe and remember its stateless, faceless, and nameless victims. Close your eyes and look: Endless nocturnal processions are converging here, and here it is always night. Here heaven and earth are on fire. Close your eyes and listen. Listen to the silent screams of terrified mothers, the prayers of anguished old men and women. Listen to the tears of children, Jewish children, a beautiful little girl among them, with golden hair, whose vulnerable tenderness has never left me. Look and listen as they quietly walk towards dark flames so gigantic that the planet itself seemed in danger.” After escaping and being recaptured by the Germans, my father was tortured for months in the notorious Block 11 of the main Auschwitz camp, known as the Death Block. Days later I receive a note in the mail from Elie: “In front of Block 11 I thought—a lot, profoundly—about your father—and about all of you.”

Elie was always unabashedly, unequivocally Jewish. But in sharp contrast to many of his contemporaries, he neither flaunted his Jewishness nor presumed to impose it on others. Rather he sought to explain its mysteries and to convey his love of the Jewish religion, of Jewish culture and tradition, of Jewish mysticism and Jewish mysteries. And he did so with deep affection and an equally profound reverence for, the subject matter and, perhaps equally important, with respect for his readers and listeners. Most important, his Jewishness was never chauvinistic or exclusionary. “To be Jewish,” he explained, “is to recognize that every person is created in God’s image and thus worthy of respect. Being Jewish to me is to reject fanaticism everywhere.”

He believed fervently, passionately, that a paramount responsibility inherent in his survival, alongside remembrance, was to speak out forcefully against indifference and against suffering, persecution, or oppression of any kind. His charge to the thousands of survivors and their children assembled in Jerusalem for the 1981 World Gathering reflected the universality of this worldview: “In an age tainted by violence, we must teach coming generations of the origins and consequences of violence. In a society of bigotry and indifference, we must tell our contemporaries that whatever the answer, it must grow out of human compassion and reflect man’s relentless quest for justice and memory; and we must insist again and again that it is the Jew who carries that message of humankind to mankind.” In this regard, his message was consistent over the years. In his Nobel lecture he spoke about the need to remember not only Jewish suffering but also “that of the Ethiopians, the Cambodians, the boat people, Palestinians, the Mesquite Indians, the Argentinian ‘desaparecidos’—the list seems endless.” His universal message remained the same even at Auschwitz, perhaps especially at Auschwitz. “As we reflect upon the past,” Elie said there in 1995, “we must address ourselves to the present and the future. In the name of all that is sacred in memory, let us stop the bloodshed in Bosnia, Rwanda, and Chechnya; the vicious and ruthless terror attacks against Jews in the Holy Land. Let us reject and oppose more effectively religious fanaticism and racial hate.”

June 2008. We are in Petra, Jordan. Elie and his wife Marion had asked me to organize an international conference of Nobel laureates for the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity. Hunger is one of the themes. “Those of us who were never hungry will never understand hunger,” said Elie. “Hunger brings humiliation. The hungry person thinks of bread and nothing else. Hunger fills his or her universe. His prayer, his aspiration, his hope, his ideal are not lofty: They are a piece of bread. To accept another person’s hunger is to condone his or her tragic condition of helplessness, despair, and death.” The afternoon of the last day of the conference he and I walk through the ruins of a 2,000-year-old Nabataean temple. “Tu te rends compte, do you realize,” he says to me, “the distance between Auschwitz and Petra?”

And finally, always, there was Jerusalem. Elie was an ardent defender of and advocate for the State of Israel, but he loved Jerusalem, both the actual city and the ethereal, incorporeal concept of the place to which Jews yearned to return for almost two thousand years; the original city on a hill that provided a psychological, spiritual refuge that even the Nazis could not take away from the child he had been in a Birkenau barrack surrounded by death and desolation. Walking in Jerusalem with Elie was a timeless experience, almost like accompanying him to a place he knew intimately, but that somehow remained out of reach. “I see myself back in my town,” he wrote in A Beggar in Jerusalem, “back in my childhood. Yom Kippur. Day of fasting, of atonement. That evening one cry bursts with the same force from every heart: ‘Next year in Jerusalem.’ On my right, among the men draped in their prayer shawls, there was one who did not pray. The next morning I saw him again at the entrance of he Bet Hamidrash, among the beggars and simple-minded. I offered him some change; he refused. ‘I do not need it, my child,’ he said. I asked him how he subsisted. ‘On dreams,’ he answered.”

For Elie, Auschwitz and Jerusalem, Sighet and Petra, Paris, New York, and Washington were all linked together in a mystical chain that existed beyond reason or explanation. Perhaps my favorite of the many stories I heard him tell is the following Hasidic tale: “Somewhere,” said Rebbe Nahman of Bratzlav, “there lives a man who asks a question to which there is no answer; a generation later, in another place, there lives a man who asks another question to which there is no answer either—and he doesn’t know, he cannot know, that his question is actually an answer to the first.”

My visits with Elie in the weeks before he died were deeply personal and emotional. He spoke nostalgically about the vacations he, Marion, and Elisha had spent with our family in San Remo, Italy, how he had been able to relax there. “I miss your father,” he said. He wanted to know about our daughter, Jodi, and our grandchildren, and whether I was satisfied with my work and career. He reminded me how he had co-officiated at Jeanie’s and my wedding, and how he had eulogized my father at his funeral more than 40 years ago. He was also one of the witnesses at Jodi’s wedding and recited a blessing at the joint bris/simchat bat ceremony when we welcomed our twin grandchildren into the Jewish community. “I promised your father I would watch over you,” he told me several times.

But we also spoke about the present, about the depressing state of politics in both the United States and Israel. And about the presidential election campaign. He told me how much he liked and respected Hillary Clinton, reminisced about his private meetings with Barack Obama, and said that while he had met Donald Trump, he was repulsed by his xenophobic rhetoric.

Sitting with him, far more frail than I had ever seen him, I realized that he had totally retained his moral and aesthetic compass. Elie could never abide crudeness or boorishness, whether in speech or in behavior. He abhorred bigotry of any kind, against Jews certainly, but with equal fervor if it was directed at any other group. In the past we had often argued politics, but now he seemed to be giving me one final assessment, a mental guide in case I should ever be uncertain where he stood. A sad reminder that I would soon no longer be able to ask him his opinion directly but would only be able to imagine what he would say and what he would advise me to do.

In his eulogy at my father’s funeral he said, “I know countless souls, sanctified by fire, will soon greet you there. … And they will embrace you as one of their own and bring you to the Heavenly Tribunal and, still higher, to the Celestial Throne, and they will say, ‘Look, he did not forget us.’ Day in, day out, from morning until late at night, everywhere and under all circumstances, even on simchas, his spirit glowed in our fire. Few sanctified the Holocaust as he did. Few suffered it as he did. Few loved its holy martyrs as he did. So they will embrace him with love and gratitude as though he were their defender.”

I can think of no more appropriate words with which to bid farewell, a most reluctant and love-filled farewell, to my friend, my teacher, my mentor, Elie Wiesel.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Menachem Z. Rosensaft teaches about the law of genocide at the law schools of Columbia and Cornell universities and is general counsel emeritus of the World Jewish Congress. He is the author of Poems Born in Bergen-Belsen.