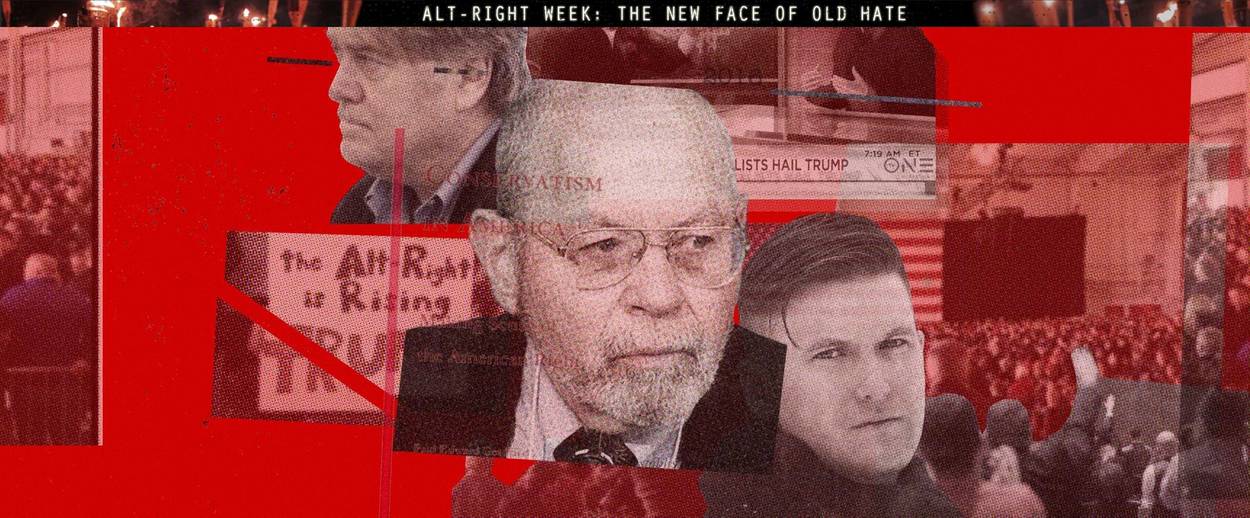

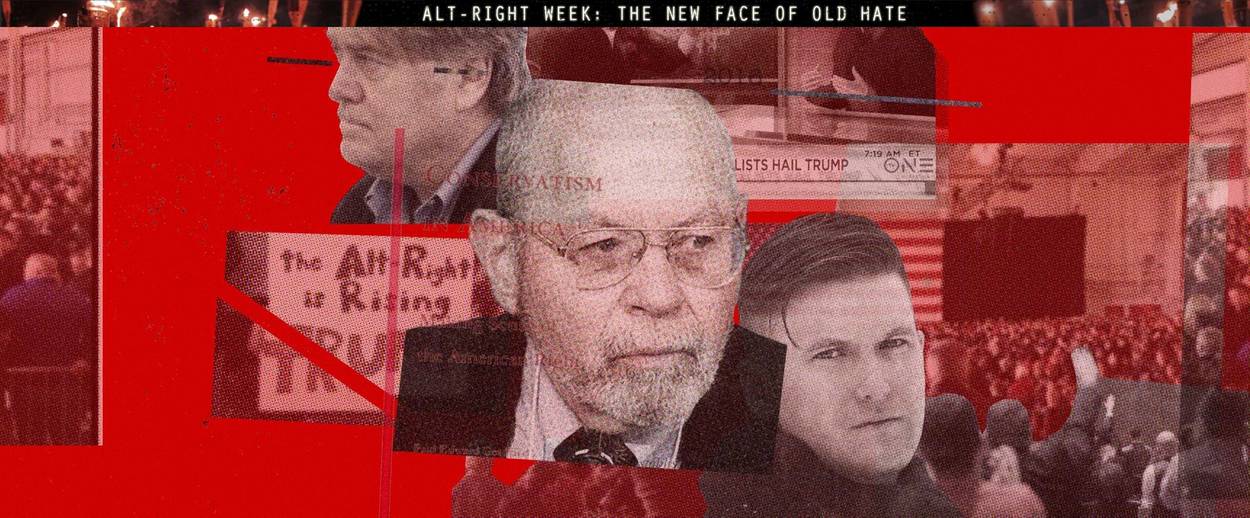

The Alt-Right’s Jewish Godfather

How Paul Gottfried—willing or reluctant—became the mentor of Richard Spencer and a philosophical lodestone for white nationalists

The night America elected Donald J. Trump president, 38-year-old Richard B. Spencer, who fancies himself the “Karl Marx of the alt-right” and envisions a “white homeland,” crowed, “we’re the establishment now.” If so, then the architect of the new establishment is Spencer’s former mentor, Paul Gottfried, a retired Jewish academic who lives, not quite contently, in Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania, on the east bank of the Susquehanna River. It’s the kind of town that reporters visit in an election season to divine the political faith of “real Americans.” A division of candy company Mars Inc. makes its home there, along with a Masonic retirement community, and the college where Gottfried taught before a school official encouraged his early exit.

Gottfried settled in Elizabethtown after his first wife died, when he decided to put family concerns ahead of professional ambitions and then set out to wage a low-level civil war against the Republican establishment. The so-called alt-right—identified variously with anti-globalist and anti-immigrant stances, cartoon frogs, white nationalists, pick-up artists, anti-Semites, and a rising tide of right-wing populism—is partly Gottfried’s creation; he invented the term in 2008, with his protégé Spencer.

The intellectual historian doesn’t have the look of a consigliere. Gottfried’s round face is covered by a trim white beard and crowned by a nearly bald head. Something about his appearance, maybe the beady, bespectacled eyes and the way his already small frame hunches forward at podiums, makes him look both timid and cantankerous. His voice has a squeaky register but his speeches, which are easy to find on the internet, are erudite and measured, ranging fluently from the legacy of fascism to the ills of multiculturalism and the “therapeutic welfare state.”

Gottfried doesn’t resolve the alt-right’s contradictions so much as he embodies them. He’s a sniffy traditionalist, a self-described “Robert Taft Republican,” with a classical liberal bent, and a Nietzschean American nationalist who goes out of his way to exaggerate his European affect. He opposes both the Civil Rights Act and white nationalism. He’s a bone-deep elitist and the oracle of what’s billed as a populist revolt. “If someone were to ask me what distinguishes the right from the left,” Gottfried wrote in 2008, “the difference that comes to mind most readily centers on equality. The left favors that principle, while the right regards it as an unhealthy obsession.”

Inequality is the alt-right’s foundational belief. In this view, there are inherent, irreducible differences not only between individuals but between groups of people—races, genders, religions, nations; all of the above. These groups each have their own distinctive characteristics and competitive advantages; accordingly, inequality is natural and good, while equality is unnatural and therefore bad and can only be imposed by force. In practice, it is typically a belief in white supremacy and a rejection of universalism.

To the ancient idea that the world is ordered by natural hierarchies the alt-right adds new wrinkles. It shows a nerdish enthusiasm for data-driven attempts to classify group cognitive abilities, an update on the social Darwinist “race science” popular before WWII that often resolves into a genes-are-destiny outlook. It also embraces concepts from the controversial field of evolutionary psychology, which attempts to explain the behavior of groups in terms of Darwinian natural selection. Because equality is both impossible and a kind of civic religion as Gottfried sees it, government attempts to enforce it are only pretexts for the state to increase its power and reach.

Railing against meddling bureaucracies and the threats they pose to liberty is a staple of conservative politics, but Gottfried’s arguments are more esoteric and more radical than anything you’d hear at a tea-party convention. Condensed, Gottfried’s theory holds that America is no longer a republic or a liberal democracy—categories that lost their meaning after the postindustrial explosion of bureaucratic apparatuses transformed the country into a “therapeutic managerial state.” Today, we are ruled by a class of managers who dress like bureaucrats but act like priests. This technocratic clerisy justifies its status by enforcing Progressive precepts like multiculturalism and political correctness, which pit different groups against each other as if they were religious edicts. As Gottfried tells it he was banished from the mainstream of political discourse for rejecting this liberal catechism. Now, versions of the same ideas that Gottfried says got him banished will be gospel in Trump’s White House.

“I view it as a partial vindication,” he told me just over a month before the presidential election, about the rise of the alt-right. “Much would depend on what Trump would do if he became president.”

***

Paul Edward Gottfried was born in 1941 in the Bronx, seven years after his father, Andrew, immigrated to America. Andrew Gottfried, a successful furrier in Budapest, fled Hungary shortly after Austria’s Chancellor Dollfuss was assassinated by Nazi agents in the “July putsch.” He had sensed that Central Europe would be squeezed in a vise between the Nazis and the Soviets and decided to take his chances in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where the family moved shortly after Paul was born. Andrew Gottfried opened a fur business in Bridgeport and became a prominent member of that city’s large expatriate Hungarian Jewish community.

The elder Gottfried was a man who “held grudges with extraordinary tenacity,” Paul recounts in his memoir, Encounters. His father had “fiery courage,” and a natural authority that impressed his son. He was a lifelong Republican who nevertheless admired FDR for beating the Nazis. But that was as far as his liberalism went; he had no time for “specious” attempts to draw universal lessons from Nazism about the American civil-rights movement or immigration policy. In all of this it seems, he was a model for his son’s intellectual life.

Though he wasn’t very religious, the younger Gottfried attended Yeshiva University in New York as an undergrad. On the plus side for the pudgy teenager, the school was full of “nonthreatening geeks,” who couldn’t bully him. But Gottfried was put off by his “bright” but “clannish” outerborough Orthodox Jewish classmates. New York was farther from Connecticut than he’d imagined. His fellow students “seemed to carry with them the social gracelessness of having grown up in a transported Eastern European ghetto.”

It used to be common even among assimilated Americans Jews from Central European backgrounds to look down on what they saw as the poorer, more provincial Jews from the Russian empire. You can see this prejudice in Hannah Arendt’s work, another author who blended “Teutonic pedantry and Jewish moral righteousness,” as a friend of Gottfried’s once described him. His classmates are clever but harried, whereas he has the aristocratic equanimity of Germanic high culture, which allows him true insight. It’s important to note not because this particular prejudice is more disqualifying than his others, but because of how deeply it informs his later writing. When Gottfried goes after the mostly Eastern-European-originating Jewish “neocons” and “New York intellectuals” he blames for kneecapping his career and refusing to give him his intellectual due, it’s not just the actual injury that wounds him, but the indignity of being laid low by his inferiors.

After graduation, Gottfried returned to Connecticut to attend Yale as a doctoral student, where he studied under Herbert Marcuse. A chapter of his memoir is devoted to Marcuse, one of the seminal intellectuals of the Frankfurt school whose critique of mass democracy profoundly shaped the new-left. Though he belonged to the Yale Political Union’s Party of the Right at the time, Gottfried “studied under Marcuse as a rapt, indulgent disciple.” In later years, one reviewer called Gottfried a “right-wing proponent of the Frankfurt school.” That description, while not strictly accurate, gives a sense of the overlap between Gottfried’s radical criticism of modern liberalism and a certain left-wing line of attack.

After graduating from Yale, Gottfried began his work as an academic and embarked on a prolific writing career, which he maintains. Over the course of 13 books and countless speeches and articles, he developed his major themes: the nature and force of history; the meaning and forms of conservatism; and in his “Marxism Trilogy,” an account of liberal democracy and the therapeutic managerial state as the hegemons of the modern world. While admiring aspects of Marx’s analysis of capitalism, Gottfried argues that Marxism was discredited by socialism’s economic failure. In the wake of this failure, Marx’s economic critique metastasized from an analysis of material conditions into a morality play. For the new post-Marxists, leftist politics were repurposed as a never-ending struggle to defeat fascism. Acting out this universalist crusade, Gottfried argues, the left became the afterlife of Christianity. “A Christian civilization created the moral and eschatological framework that leftist anti-Christians have taken over and adapted,” he wrote. “It is the fascists, not the Communists or multiculturalists, who were the sideshow in modern Western history.”

At the heart of the alt-right is a project, carried out by Gottfried and others, to revise the historical record of WWII. If there has been a left-wing political impulse to expand the meaning of fascism far beyond its original context, part of the right responds by making it so particular to interwar Europe that it defies any historical analogy.

In his book Fascism: The Career of a Concept, Gottfried argues that Spanish and Italian “generic fascism” belonged to a different genus than German Nazism. Hitler, the argument goes, was not really a fascist in the generic sense, but a far-right counter-revolutionary response to Stalin. A few years ago this might all have been interesting enough, grounds for contentious but seemingly abstract historical debates. Today, it’s clear that it also serves a political purpose. It takes away the power of “fascist” to stigmatize far-right politics. At the same time, it also helps to rescue a whole host of concepts tainted by association with fascism, like ethnic nationalism and “race science,” making it safe again for the right to openly advocate them.

***

The alt-right is the direct heir of the paleoconservatives, a first-draft attempt at a conservative insurgency in America that appeared to peak in the 1990s. The name “paleoconservative” was coined by Gottfried himself in 1986, which means he is batting a thousand when it comes to naming right-wing opposition movements.

In the decade before Gottfried arrived at Yale, postwar conservatism was born in a “fusionism” that brought together southern and religious traditionalists, Libertarians, and other disparate groups who shared a commitment to aggressive anti-Communist policies. It evolved as “a series of movements rather than the orderly unfolding of a single force,” Gottfried wrote in his 1986 history, The Conservative Movement. Not all the movements got along, and not long after they came together, the conservative establishment, led by the influential magazine National Review and its editor, William F. Buckley, started kicking people out. The so-called purges started with the John Birch society, radical right-wing anti-Communists and conspiracy theorists—think Alex Jones followers—whom Buckley excommunicated from the movement in 1962. After the Birchers, conservatives, again led by National Review, eventually pushed out white supremacists and anti-Semites, including some of Gottfried’s friends. These are major events in the official conservative history that showed the movement grappling with the legacy of WWII and the right’s own history of racism and bigotry.

Those pushed out the door saw it differently. If the purges are an important chapter for establishment conservatives, they are a foundational myth for the putative victims. These parties dismissed the charges of racism and anti-Semitism on the right as trumped up, or alternately waved them away as mere individual prejudice; the real threat, they argued, was from the purges themselves. By trying to prosecute intolerance, the conservative establishment was carrying out its own version of Soviet show trials while adopting the language and principles of their enemies on the left. Of course, the purged weren’t killed but “anathematized,” to use the victims’ preferred language, which could mean the difference between a faculty chair with a view of the Hudson and one overlooking the Susquehanna. Not trivial, but less gruesome than you’d gather from some partisan histories.

Neoconservatives emerged in the 1970s. They were a group of mostly Jewish and Catholic former leftists who moved right in reaction to the illiberalism of the 1960s’ new-left and out of its conviction that the failure of Great Society social programs proved that culture influenced behavior more than state policy. The original neocons included a number of former Trotskyites and Socialists but were staunch anti-Communists. This led them to advocate an interventionist role for the military, first as a bulwark against the Soviet Union and later as a guarantor of the postwar U.S.-led global democratic order. As the neocons rose through the conservative ranks, intellectual and institutional warfare ensued among them and the movement’s harder-right and traditionalist wings. The anti-neocons, like Gottfried, accused their enemies of being impostors—Wilsonian internationalists and Social Democrats in wolf’s clothing.

Paleoconservatives was the name Gottfried gave to the small group of anti-neocons who formed the internal opposition after the conservatives’ “fusion” coalition broke apart in the late 1980s. In The Conservative Movement, Gottfried voices the paleos’ heroic self-conception: “[They] raise issues that the neoconservatives and the left would both seek to keep closed … about the desirability of political and social equality, the functionality of human-rights thinking, and the genetic basis of intelligence … like Nietzsche, they go after democratic idols, driven by disdain for what they believe dehumanizes.”

In practice, paleoconservatives took some esoteric positions, like an embrace of Serbian nationalism that had little hope of catching on in the heartland or anywhere but the Marriott conference rooms where the paleos kept their fire burning. Because the neocons were disproportionately Jewish and the paleos keenly interested in proportions of Jews in the political establishment, there was allegations and evidence of anti-Semitism in their disputes. Gottfried complained regularly in his writing about “ill-mannered, touchy Jews and their groveling or adulatory Christian assistants,” his phrase for neocons who he claimed had hijacked the Republican Party and American policy. This belief that Jews were cultural and political saboteurs was common among some paleos, but Gottfried liked to put it in language he got away with as an indulgence of his own Jewishness. For their part, the neocons regarded the paleos as wannabe-European aristocrats with no real place in America’s democratic tradition. At worst, they were high-toned racists and anti-Semites; tweedy authoritarians who had come to hate their own country.

Like most political infighting, the conflict had a personal element, as Gottfried admits in a passage characteristic of his wounded self-awareness: “My understanding of neoconservatives, it might be argued, is insufficiently generous or insufficiently nuanced, but if that is the case, I would like to hear the neoconservatives’ response. Until now they have not replied to me, except by treating me as a liar or a lunatic.” This assessment seems fair enough. In a long article on the eve of the Iraq war that denounced the paleos as “unpatriotic conservatives,” leading neocon and Bush speechwriter David Frum mentions Gottfried only once, when he describes him as “the most relentlessly solipsistic of the disgruntled paleos, who has published an endless series of articles about his professional rebuffs.”

It is true that the paleos’ ranks included a fair number of cranks, racists, and anti-Semites whose prejudices were essential to their politics. But this exists uncomfortably alongside another aspect of the paleos—they were capable of some trenchant ideas about modernity and the American century. Where establishment liberalism went in for sentimental pieties and movement conservatism offered platitudes in place of wisdom, the paleos could be incisive and unsparing. They were relentless critics, for instance, of the Bush-era bromide that Iraq was only an invasion away from successful democracy—and, more generally, of preventive wars carried out in the name of democratic universalism. The paleos were also attuned to the costs of global trade—not only the loss in jobs but in community and self-worth—in a way that neoliberals and neoconservatives often were not.

Trumpism has revived a longstanding disagreement between the paleos and neocons over the basis of nationhood. Where neocons subscribed to the “propositional” nation, in which national identity is a function of political principles and creed, the paleos took a different view. They argued that nations were defined by the specific cultural and historical heritage of their founders. So “Americanness,” for instance, is not established by political ideals as much as by the legacy of Protestant English settlers from whose characters and milieu those ideals emerged naturally. The implications for immigration policy are clear—the more new immigrants’ backgrounds differ from the culture and belief of the original English settlers, the more they will transform Americanness. Some paleos like Gottfried framed this idea in cultural and civilizational terms, while others, like the influential Samuel Francis, advocated explicitly for white nationalism.

In 1986’s The Conservative Movement, Gottfried also devotes a section to “the new sociobiology” that emerged in the 1960s and its influence on the right. The book describes the field’s struggle to distinguish its social Darwinism from the “corrupted version” that was “exploited by the Nazis.” It concluded that “a biological reconstruction of sociology was unlikely to win many conservative adherents (apart from racialists).” Four years after that essay was published, Jared Taylor, now one of the most prominent alt-right figureheads, founded the white nationalist, racialist American Renaissance.

Taylor succeeded because he “avoided the obsessions and crankiness that have, unfortunately, characterized much of American racialism,” wrote erstwhile Gottfried disciple Richard Spencer. “With Jared and AmRen,” he noted, “there is a certain radicalness in mainstreaming, in presenting ideas that have world-changing consequences in packages that seem mellow and respectable.”

Though it wasn’t clear at the time, the paleos’ influence crested with Pat Buchanan’s failed run to be the Republican presidential nominee in 1992. Gottfried served as an adviser for the campaign, which scored an impressive win in the New Hampshire primary and effectively foreshadowed Trump’s strategy. Buchanan was too stiff and socially conservative to make Trump’s stylized alpha-male sales pitch, but he ran on a similar nationalist platform, promising to restrict immigration while opposing globalism and multiculturalism. A key architect of the Buchanan strategy and Gottfried’s friend, Samuel Francis, articulated in passing the spirit that animated their movement and that they would pass on to their heirs in the alt-right. “I am not a conservative,” Francis said, “but a man of the right, perhaps of the far-right.”

The War on Terror and invasion of Iraq meant that the paleocons were marginalized. Always self-critical, Gottfried recognized when his movement had become moribund, and along with a small group of fellow travelers on the far right—or the dissident right, as they then called it—Gottfried began plotting what would come next. He observed that the paleos had not appealed to young people. Also, they were missing an overriding principle to unite them. The original conservative fusionists had anti-Communism. What would the postpaleos have?

***

The first decade of the 21st century, after the War on Terror sidelined the anti-war paleocons and before Trump amplified their successors in the alt-right, were the wilderness years for Gottfried and his fellow thinkers of the far-right. In the dark, a few different things started growing. French Nouvelle Droite philosophers and other European “identitarians” informed a new ideological style that embraced ethno-nationalism but rejected purity tests and drew openly from leftist writers like Antonio Gramsci. At the same time, the paleo interest in sociobiology and “race realism” spread across the internet thanks to bloggers like Steve Sailer.

Anti-PC sentiment became the binding element in the new fusionism Gottfried hoped to achieve. The Obama presidency both stoked the anti-PC sentiment and inspired a millenarianism that made segments of the right open to radical new ideas. There was a certain itchiness, too, in the culture at that time. What once felt like a bug squirming in the American psyche—that the consolations of the culture industry and consumerism were not enough—burrowed into the spaces where wages stagnated, prospects shriveled, and the old liberal meritocracy hollowed out.

In a 2009 essay, Gottfried wrote: “To the extent that anything resembling the historic right can flourish in our predominantly postmodernist, multicultural and feminist society—and barring any unforeseen return to a more traditionalist establishment right—racial nationalism, for better or worse, may be one of the few extant examples of a recognizably rightist mind-set.” He praised white nationalists in the essay for acting as a battering ram against multiculturalism. And yet despite also describing this cohort as, in his experience, “articulate gentlemen with extraordinarily high intelligence,” he did not actually endorse their views, which he called reductive and impractical.

When I spoke with Richard Spencer by telephone a few days after the first Trump-Clinton debate in late September, he couldn’t resist making the generational conflict with his former mentor explicit. “Despite his demands that we move beyond paleoconservatism, Paul still is himself a bit of a paleocon. It’s still about defending an American republic.” And, if there was any remaining doubt, he added: “There’s a revolutionary heart to the alt-right, and I don’t think there’s a revolutionary heart to Paul Gottfried.” Spencer claims that he’s the one who actually invented the name “alternative right.” He says he came up with it as a headline for Gottfried’s speech, which never uses the words, when he published it in Taki’s Magazine, where he worked as an editor. Gottfried insists they “co-created” the name.

Spencer had moved toward the revolutionary wing of the new movement by 2010 when he created the website Alternative Right, which helped shape and popularize the loosely-knit alt-right movement. In the early 2010s, Spencer’s site and a handful of other influential outlets defined the aesthetic and political motifs of the current alt-right. A mix of shock-and-meme culture, metapolitics, right-wing social values, and anti-bourgeois posturing, it appealed to an audience of young reactionaries. It gave them something to do with their vast amounts of time online and sharpened their “fuck the normies” rage to a radical edge. Ethnic identitarianism anchored that rage and defined their enemies. Appealing to the nerdier inclinations of these adherents, the racial mythos was complemented by the biological determinist part of the program with its strong data bias. If, in a sense, white-nationalist identity politics was just another form of the left-wing identity politics that they claimed to despise, so be it; let the minorities and liberals have a taste of their own medicine.

“American society today is so just fundamentally bourgeois,” Spencer told me over the phone. “It’s just so, pardon my French … it’s so fucking middle-class in its values. There is no value higher than having a pension and dying in bed. I find that profoundly pathetic. So, yeah, I think we might need a little more chaos in our politics, we might need a bit of that fascist spirit in our politics.”

The fight over the degree of adherence to white-nationalist doctrines was an open one within the alt-right. “The Alt-Right Means White Nationalism … or Nothing at All” read the headline of an August 2016 editorial by Greg Johnson, editor of the influential alt-right publication Counter Currents. Johnson was responding to attempts to redefine the movement away from that position by people like Milo Yiannopoulos, the Breitbart journalist who insists he’s only a fellow traveler and not a member of the alt-right. “Milo seems to be defining European identity as hyperliberalism,” Richard Spencer tweeted in June. “This leads nowhere.”

While Gottfried calls Yiannopoulos his favorite figure on the alt-right for his opposition to government-led social policy and political correctness, this puts him awkwardly in the position he once accused the neocons of occupying—diluting the authentic core of right politics. “I am not beloved by the alt-right,” Gottfried told me. “I’m sort of somebody who remains aloof.” He has some hope for “collaboration among all the elements of the dissident right,” but within limits. “Where I would draw the line personally is white nationalists. They are not people I would want to include in my alliance. They sometimes say outrageous things and they are sitting ducks for the Southern Poverty Law Center and other leftist groups.”

In September, Gottfried also told me, “I have had no ideological collaboration with Richard Spencer for years, and given the direction he’s going, I doubt that I’ll have much to do with him politically in this lifetime.” But this isn’t strictly true if you count the 2015 book they co-edited published by Spencer’s Radix imprint. Nor is it true if you count even more recent mentions in print.

In August of this year, less than two months before we spoke, Gottfried wrote a column defending the alt-right in which he described Spencer as a “charismatic presence, in contrast to the nebbishes for Hillary.” He went further: “I fully share [Spencer’s] contemptuous attitude toward multicultural totalitarianism, and unlike Conservatism Inc., Richard is fearless in going after our self-appointed thought censors.” But added, finally, “I wish Richard would think more often before he blurts out reckless indiscretions. Shocking one’s listener has its limits, certainly in terms of traditional standards of taste.”

Speaking of Spencer and of himself, Gottfried said, “I think it is probably a trick that history plays on thinkers. But I think you’re right—he says that I’m his mentor. I think I’m his reluctant mentor, I’m not particularly happy about it.” He sighed. “Whenever I look at Richard, I see my ideas coming back in a garbled form.”

There is a shearing, centrifugal force to Gottfried’s intellect. It splits the center and flings ideas out; they land where they will. For more than 20 years, he has tried to build a postfascist, postconservative politics of the far-right. That Spencer and his acolytes wanted to cross the threshold into fascist thought and beliefs can’t really be a surprise. And unlike Gottfried, whose relentless iconoclasm has also helped insulate him from certain temptations, most people, and especially those with strong interests in fascism, are turned on by power. If he has unleashed a force in the alt-right that will finally destroy the detested managerial state, it’s a force that has people like Richard Spencer at its core. Since last week, when Spencer declared “Hail Trump” at a valedictory press conference at which attendees were photographed sieg heil-ing, there have been attempts by others on the alt-right to write him off as marginal and to rebrand their movement. If they are able to successfully rename themselves, it won’t change this: Neo-nazism, while not the whole story, is one part of the alt-right, just as the alt-right is not nearly the whole story of Trump’s victory but played a crucial part.

The political crackup of the past year has aroused a level of fear and despair, and an almost-erotic thrill—all of it backed by the threat of violence—that no president will ever fully satisfy or exorcise. Night hasn’t quite fallen yet on the old order, but it’s dusk—the gloaming hour. We aren’t even ready yet for a strange beast to be born. Instead, we’re stuck for now with the odd pairings of familiar forms, like the union of racists and anti-anti-racists that Gottfried helped pioneer, and which is now a staple of the alt-right.

“I just do not want to be in the same camp with white nationalists,” Gottfried told me. “As somebody whose family barely escaped from the Nazis in the ’30s, I do not want to be associated with people who are pro-Nazi.” But it is too late for that. As he once wrote about the followers of Leo Strauss: “One knows the tree by the fruit that it bears.” The fruit is strange.

Jacob Siegel is Senior Editor of News and The Scroll, Tablet’s daily afternoon news digest, which you can subscribe to here.