So when does the other shoe drop? Who’s going to break the story proving beyond a shadow of a doubt that the president of the United States is so deeply connected to Russian President Vladimir Putin that the White House has become a Muscovite colony in all but name?

Time to use some common sense—it’s not going to happen, there is no story. The narrative that Donald Trump is effectively Putin’s prison wife is an information operation orchestrated by Democratic hands, many of whom served in the Obama administration, sectors of the intelligence community, and much of the American press. The purpose of the campaign is to delegitimize Trump’s presidency by continuing to hit on themes drawn from the narrative that Russia “hacked” the election and stole it away from Clinton.

The narrative is contorted because it’s not journalism. It’s a story that could only make sense in a profoundly corrupted public sphere, one in which, for instance, Graydon Carter is celebrated for speaking truth to power with an editor’s letter critical of Trump in a magazine that has no other ontological ground in the universe except to celebrate power.

Oh, sure, there are regular hints that there’s still more to come on Trump and his staff’s ties to Russia—the big one is about to hit. But the steady sound of drip-drip-drip is the telltale sign of a political campaign, where items are leaked bit by bit to paralyze the target. Journalists, on the other hand, have to get their story out there as quickly, and as fully, as possible because they’re always worried the competition is going to beat them to it.

No, if Trump really was in bed with the Russians, the story would already be out there, and I’m pretty sure it would have had a Wayne Barrett byline.

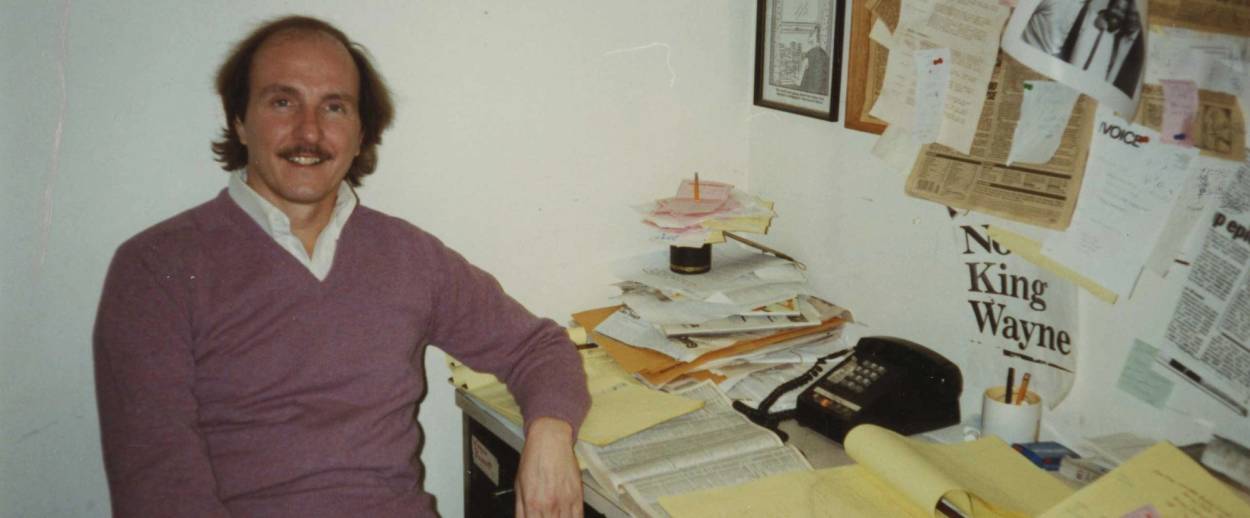

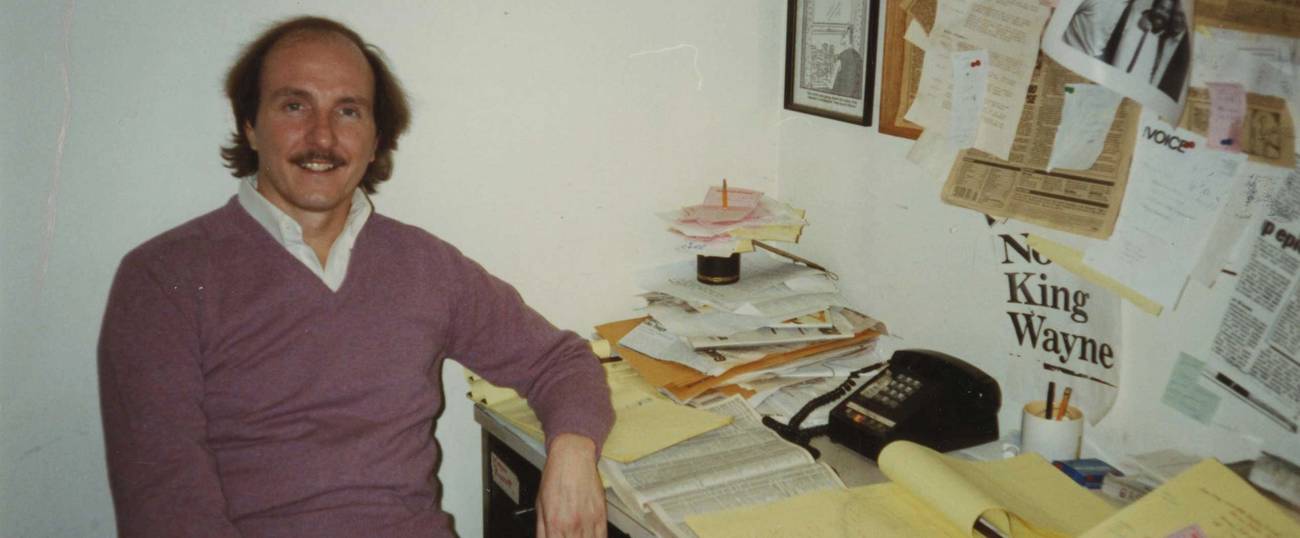

When I worked at the Village Voice in the mid-1990s, my office was right around the corner from Barrett’s and his bullpen of interns, a team that kept the heat on local politicians like Rudy Giuliani, Ed Koch, and others. Barrett was the first journalist who wrote at length about Trump, starting in the mid-1970s. His biography, Trump: The Deals and the Downfall, was published in 1992, and reissued in 2016 asTrump: The Greatest Show on Earth: The Deals, the Downfall, the Reinvention.

When Trump won the nomination and the pace of Trump stories picked up, Barrett became something of an official archivist, with reporters visiting his Brooklyn house to go through his files in the basement. Anyone who wanted to know what Trump’s deal with Russia was, for instance, would want to talk to Barrett because either he or his team of interns, 40 years’ worth, would have it. After all, New York City is the world capital for information on Russians, even better than Israel—because even though the city got a smaller number of post-Cold War immigrants, New York got a higher percentage of mobsters.

Let’s compare the institution of Wayne Barrett, a subset of the institution of journalism, to the so-called Russia dossier, the document placing Trump in a shady underworld governed by Putin and other Russian thugs. The former includes not only Barrett’s body of work over nearly half a century, but that of the hundreds of journalists he trained, and many thousands of sources whose information is, therefore, able to be cross-checked.

The latter, a congeries of preadolescent pornographic fantasy and spy tales, was authored by a British intelligence officer who has gone to ground since the dossier was made public. The dossier started as work made for hire, first paid for by Republican opponents of Trump and then the Clinton camp, and is sourced to Russian “contacts” who are clearly using the document as an opportunity to proliferate an information operation for perhaps various and as yet unknown purposes. The former is journalism. The latter, part oppo research and part intelligence dump, is garbage. Clearly, it is also the new standard in the field, which is why journalists on both sides of the political spectrum are boasting about their willingness to let their bylines be used as bulletin boards for spy services and call it a “scoop.”

Barrett had Trump on a whole variety of issues, but check the records yourself—up until the day of his death, the day before Trump’s inauguration, there’s nothing on Trump and Putin. Does this mean Trump is totally clean? Who knows? But the journalists now clamoring like maniacs about Trump’s ties sure aren’t going to find it. They’re thin-skinned hacks outraged that Trump dared violate the inherent dignity of that most important of American political institutions, the presidential press conference. And as we all know, this is the apex of real journalism, where esteemed members of the press sit side by side with other masters of the craft to see who gets their question televised.

Does Trump really believe the media are “an enemy of the people”? Please. Let’s remember how he rode his wave to fame on the back of the New York Post’s Page Six (and Graydon Carter’s Spy magazine). He still speaks regularly to the head of CNN (aka “Fake News”), Jeff Zucker, who put him on The Apprentice and Celebrity Apprentice at NBC, where Trump sat atop the Nielsens for 13 years. Trump uses his Twitter feed to boost his replacement Arnold Schwarzenegger’s ratings because the president still has a credit as executive producer. No, Trump doesn’t hate the media. Like Howard Stern, he sees himself as the king of all media. What he’s doing here is playing gladiator in front of an audience that wants to see the lions slain.

Maybe Trump deserves the heat with the fake Russia stories. He backed the Obama birth certificate story, and what goes around comes around. But the American public sure doesn’t deserve a press like this.

Trump adviser Steve Bannon calls the media the opposition party, but that’s misleading. Everyone knows that the press typically tilts left, and no one is surprised, for instance, that The New York Times has not endorsed a Republican candidate since 1956. But that’s not what we’re seeing now—rather, the media has become an instrument in a campaign of political warfare. What was once an American political institution and a central part of the public sphere became something more like state-owned media used to advance the ruling party’s agenda and bully the opposition into silence. Russia’s RT network, the emir of Qatar’s Al Jazeera network—indeed, all of the Arab press—and media typically furnished by Third World regimes became the American press’ new paradigm; not journalism, but information operation.

How did this happen? It’s not about a few journalists, many of whom still do honor to the profession, or a few papers or networks. It’s a structural issue. Much of it is because of the wounds the media inflicted on itself, but it was also partly due to something like a natural catastrophe that no one could have predicted, or controlled.

I was at the Voice when the meteor hit. Like many papers back then, dailies and weeklies, the Voice made its money on classified advertising. The New York Times, for instance, had three important classifieds sections—employment, automotive, and housing—but if New Yorkers really wanted to find a great apartment, they’d line up at the newsstand on 42nd Street to get a copy of the Voice hot off the press.

And then the internet came along, and it was all there in one place—for free. The press panicked. The Voice’s publisher at the time, David Schneiderman, announced to the staff that the paper was going free. It made no sense, he argued, to keep charging $1 for what consumers could get on the internet for nothing.

Here’s how the staff heard it: Who would want to pay $1 a week to read Nat Hentoff on civil liberties, Robert Christgau on music, Michael Musto on New York nightlife—or Wayne Barrett on the follies of real-estate mogul Donald Trump? That is, who would want to pay $1 a week to feel themselves a part of what the Village Voice had made them feel part of for decades? But at the time, devaluing content was in fashion—which meant, as few saw back then, the profession was digging its own grave.

The American press’ new paradigm: not journalism, but information operation.

In midtown, Tina Brown had taken The New Yorker, a notoriously sleepy rag that entry-level assistants stacked in a corner of their studio apartments to spend a rainy Saturday with a 10,000-word Ved Mehta article, and turned it into a hot book that everyone from Bill and Hillary Clinton to Harvey and Bob Weinstein was talking about. “Buzz” was Tina’s catchword, and she made her writers stars. But something else was happening on the business side that wasn’t good for the content providers.

Before Brown, The New Yorker made its money by selling the magazine to readers who wanted to feel like a part of the world only The New Yorker made available, a cozy world reflected by the modest, but very profitable, number of subscriptions, which hovered around 340,000. Advertising was an afterthought. It may have been the only magazine in history at which the business side held ads because there wasn’t space for them, or because, well, Mr. Shawn might not like them.

Condé Nast owner Si Newhouse, who bought The New Yorker in 1985, and publisher Steve Florio turned the business model on its head when Brown came on in 1992. Forget about making readers pay for content; instead, bill advertisers for access to your readers—charge them for eyeballs. They slashed the subscription price dramatically and readership swelled by many hundreds of thousands. This enabled the sales team to bump up ad rates to levels on par with other Condé Nast glossies, essentially fashion catalogs, that enjoyed much larger readerships, like Vogue, GQ, and Glamour.

The paradox was that The New Yorker lost money because each of the new subscriptions was costly. Paper, printing, and postage are expensive, and even the new ad rates couldn’t cover the costs now that circulation had grown to something like 800,000—not monthly like Vogue, but weekly.

Instead of paying for the cost of high-level reporting and editing, subscribers now cost The New Yorker money. In Brown’s last year at the magazine, The New Yorker lost $10 million—a giant black hole that her successor would endeavor mightily to fill while retaining the magazine’s new subscribers, who had little knowledge of or attachment to the magazine’s prior mix of literary reporting and sophisticated whimsy. If the subscribers didn’t feel interested and flattered, the magazine was sunk.

With a new media model that devalued content, no one had a very clear picture of the problems ahead. The future was further obscured by what seemed to be an astonishing reflorescence of the press, with tiny internet startups throwing lavish parties in Manhattan bistros and paying writers Condé Nast-level fees. The internet was the messiah, everything was great—until the IT bubble burst and media giants like TimeWarner stopped throwing money at a platform they didn’t understand. So now who was going to pay?

For the next decade, the media couldn’t decide which slogan of the moment carried more weight—“content is king” or “information wants to be free.” Sure, you can give away “information,” but someone has to find some way to cover expenses, and yet no one had figured out how to make internet advertising work. Maybe you really could charge for content. Of course you could—The New Yorker had done it for decades.

Even if you bring your own glass to a lemonade stand, there is no 8-year-old entrepreneur who is not going to charge you for his product. Why didn’t media grandees get it? When they saw their ad-based business model collapse, why didn’t they do the logical thing and raise the price on consumers? Sure, they’d lose some readers and have to cut some staff and departments, but they’d have established a fundamental defense of the product, the industry, and the institution itself—news is worth paying for.

As the old Chinese saying has it, the first generation builds the business, the second generation expands it, and the third spends it all on Italian shoes, houses in the Hamptons, and divorces. For the most part, the people inheriting these media properties didn’t know what they were doing. It took The New York Times more than a decade to settle on billing consumers for its product—after giving it away, charging for it, giving it away again, then billing for “premium content,” etc. By then, it was too late. Entire papers went under, and even at places that survived, the costliest enterprises, like foreign bureaus and investigative teams, were cut. An entire generation’s worth of expertise, experience, and journalistic ethics evaporated into thin air.

In January, Bannon told the Times that the press doesn’t “understand this country. They still do not understand why Donald Trump is the president of the United States.” But the Times had already acknowledged its blunder in a letter to its readers after the election. However, neither Bannon nor the Times seemed to grasp the logistical reasons for the failure—it wasn’t because the paper of record slants left, or because it was too caught up in its own narrative. It’s in large part because it had long ago cut the regional bureaus in the South, the Midwest, etc., that would’ve forced reporters to speak to Americans outside the urban bubble and thereby explain to readers what the world looks like once you wander off the F train.

By the time two planes brought down the World Trade Center towers in September of 2001, everyone in the industry knew the media was in big trouble. The Iraq War partially hid and then later amplified that fact. The media spent millions it didn’t have for coverage it gave away free of a war that the press first supported and then turned against. If journalists prided themselves on their courageous about-faces, to much of their audience it further discredited a press whose main brief is not to advocate for or against, but to report facts.

This is the media environment that Barack Obama walked into—where Post columnist David Ignatius was no more important a media figure than Zach Galifianakis, on whose precious and often funny internet show Between Two Ferns the president marketed the Affordable Care Act. I suspect the Obama White House was a little sad that the press we’d all grown up with was basically dead. As Ben Rhodes, former national security adviser for strategic communications, told The New York Times Magazine, “I’d prefer a sober, reasoned public debate, after which members of Congress reflect and take a vote. But that’s impossible.”

He was right. What was once known as the prestige media became indistinguishable from the other stuff that Facebook gives away. Was it The New York Times or BuzzFeed that published that video about cats terrorized by cucumbers? Or was it Fake News because, in fact, cats aren’t scared of vegetables? It doesn’t matter where it came from, because there is no longer any hierarchy in the press. The media, as Thomas Friedman might say, is flat.

Obama didn’t kill journalism, but he took advantage of it in its weakness, because he knew the press would do anything to feel relevant again. All those 27-year-olds at the Times, the Washington Post and others hired as bloggers—“who literally know nothing,” as Rhodes told the Times Magazine—when the foreign and national bureaus were closed, they didn’t know it wasn’t OK to be a journalist and a political operative at the same time. They thought it made them more valuable, even patriotic, to put themselves in the service of a historic presidency. And they’d replaced for pennies on the dollar all the adults who could have taught them otherwise.

That’s the raw material out of which the Obama administration built its echo chamber, the purpose of which was to drown out the few remaining vestiges of journalism in order to sell the president’s policies. And there really were real journalists still putting in the hours, still doing the work, but the echo chamber, a relentless, frenzied chorus of incoherent and nearly illiterate prose, shouted them down.

Yes, it would have been nice if the American public had a chance to discuss a policy of vital importance to our national security, like the Iran nuclear deal, but the press congratulated itself for silencing those who dissented from Obama’s signature foreign-policy initiative. These weren’t simply critics or opponents of the White House, they weren’t just wrong; no, they were warmongers, beholden to donors and moneyed interests and lobbies, they were dual loyalists.

But it was all OK for the press to humiliate and threaten Obama’s opponents in accordance with the talking points provided by Obama administration officials—they were helping the president prevent another senseless war. That’s for history to decide. What everyone saw at the time was that the press had put itself in the service of executive power. This was no longer simply tilting left, rather, it was turning an American political institution against the American public.

Now with Trump in the White House, commentators on the right are critical of those angry with the press for calling out Trump on the same stuff that Obama got away with. Let’s be above it, they argue. Just because Obama did it doesn’t make it OK for Trump to do it. Fine, obviously, call out Trump—but this isn’t about playing gotcha. It’s about a self-aggrandizing press corps gaslighting the electorate. The public is astonished and appalled that the media has now returned after an eight-year absence to arrogate to itself the role of conscience of the nation.

It’s not working out very well.

Consider the Washington Post, whose new motto is “Democracy Dies in Darkness,” which presumably was OK’d by owner Jeff Bezos, the man who closed virtually every independent bookstore in America. Here’s a recent story about riots in Sweden:

Just two days after President Trump provoked widespread consternation by seeming to imply, incorrectly, that immigrants had perpetrated a recent spate of violence in Sweden, riots broke out in a predominantly immigrant neighborhood in the northern suburbs of the country’s capital, Stockholm.

You’ve probably never seen the phrase “seeming to imply” in the lede of a story in a major American newspaper before—a news story. So did Trump imply, or seem to imply? How are readers supposed to parse “incorrectly” if the story is about the reality of riots in a place where Trump “seemingly” “implied” there was violence? So what’s the point—that Trump is a racist? Or that Trump can see the future?

The press at present is incapable of reconstituting itself because it lacks the muscle memory to do so. Look at the poor New Yorker. During the eight years of the Obama administration, it was best known not for reported stories, but for providing a rostrum for a man to address the class that revered him as a Caesar. Now that the magazine is cut off from the power that made it relevant, is it any wonder that when it surveys the post-Obama landscape it looks like Rome is burning—or is that the Reichstag in flames?

The Russia story is evidence that top reporters are still feeding from the same trough—political operatives, intelligence agencies, etc.—because they don’t know how to do anything else, and their editors don’t dare let the competition get out ahead. Why would the Post, for instance, let the Times carve out a bigger market share of the anti-Trump resistance? And what’s the alternative? Report the story honestly? Don’t publish questionably sourced innuendo as news?

And still, you ask, how could the Russia story be nonsense? All the major media outlets are on it. Better to cover yourself—maybe it’s true, because the press can’t really be this inept and corrupt, so there’s got to be something to it.

I say this not only out of respect for a late colleague, but in the hope that journalism may once again merit the trust of the American public. Wayne Barrett had this file for 40 years, and if neither he nor the reporters he trained got this story, it’s not a story.