Russian Manipulations, Past and Present

Do Russians historically prefer Republicans to win over Democrats?

“Do Russians historically prefer Republicans to win over Democrats?” Devin Nunes, the Republican chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, posed this question the other day. He was addressing an exceptionally murky side-debate of the larger controversy over Russia’s intervention into the election—a side-debate so obscure it can barely be described, given that mostly it has taken place in the bowels of the intelligence agencies, and has taken place secondarily in classified settings for the House committee, and has spilled into public view only because one of the committee members tripped over his own secrets and blurted out a classified phrase or two. And even then, the controversy would never have emerged, except that Ryan Lizza of The New Yorker picked up on it and described as much of it as he could discover. The intelligence agencies, it would appear, have given some thought to Russian views of American politics—the views of the Russian government, that is. And, in the course of contemplating this theme, the American agencies do seem to have spoken of an historic Russian preference for Republicans over Democrats.

Only, can this be right? That was Devin Nunes’s question. The notion of any such preference has evidently aroused skepticism in Nunes’s committee, and the skepticism has led to a worry about the intelligence agencies and their political judgment. In The New Yorker Lizza has expressed a skepticism of his own, which has led him to put a question to somebody who ought to know. This is Oleg Kalugin, a well-known defector from the KGB. The Russians in the past: Did they prefer the Republicans? “No, that’s not true,” Kalugin told Lizza. “We always supported the Democrats.” And Kalugin explained that, from a Russian standpoint, the Democrats have always been more reasonable.

I do not pretend to have any spooky information of my own about Russian maneuvers past and present, but, even so, my response to Lizza’s report and the side-debate is to express a skepticism at the skepticism. I wonder if Kalugin and the skeptics haven’t forgotten a complicating wrinkle in America’s political history. The Republican Party during the last half-century has always contained two schools of foreign-policy thinking, and not just one—a hard-line Cold War school, and also a Kissingerian school. The Cold Warriors over the decades have wanted to liberate Russia’s unfortunate neighbors and, if possible, to diminish or even overthrow the despotism in Russia itself. But the Kissingerian goal has always been different. Back in the days when Kissinger himself was Richard Nixon’s National Security Advisor and then Secretary of State, he and Nixon wanted to get Russia to agree to be a great power in a conservative version, instead of a revolutionary version; and they wanted nothing else. They wanted the Russians to abandon any effort to expand their domination into Western Europe and the rest of the world—and, instead, to content themselves with dominating their own region, and doing so in their own style.

How should the Russians have felt about the Republican Party, then? It depends. The Russians had every reason to look with horror upon the Cold War hard-liners. But, in the degree to which they were willing to confine their ambitions to their own oversized chunk of the world, they also had reason to look with respectful appreciation upon the Kissingerians. And so the question arises: Did the Russians, back in Soviet times, ever go so far as actually to intervene in an American election on behalf of the Republican Party in its Kissingerian mode? This is Devin Nunes’s question, except that I have rendered it more precise. I can answer. They did.

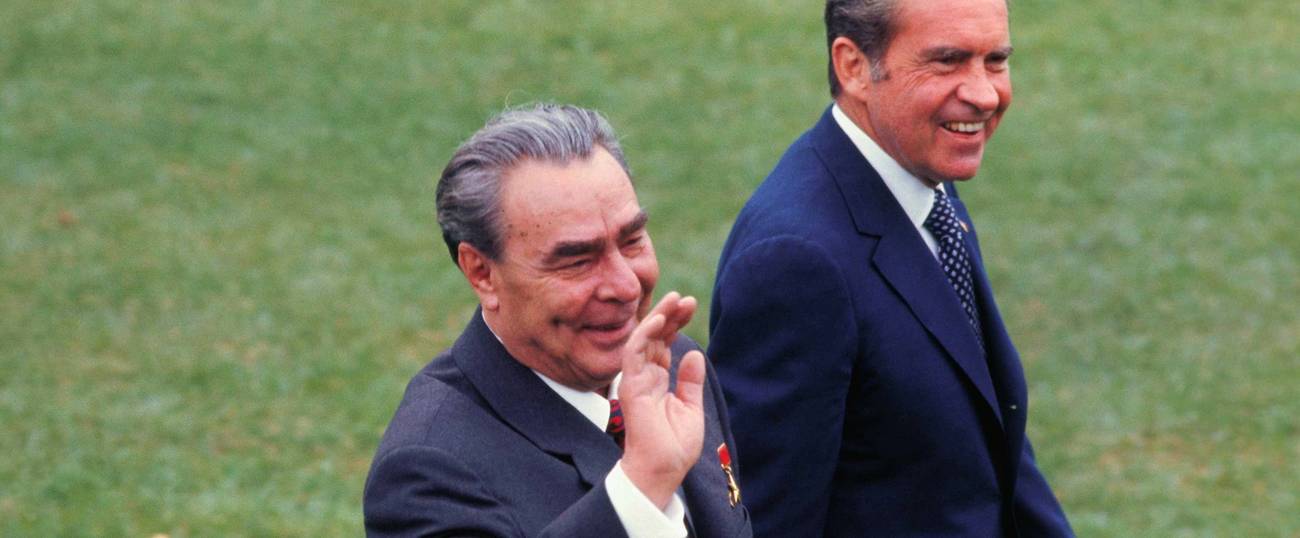

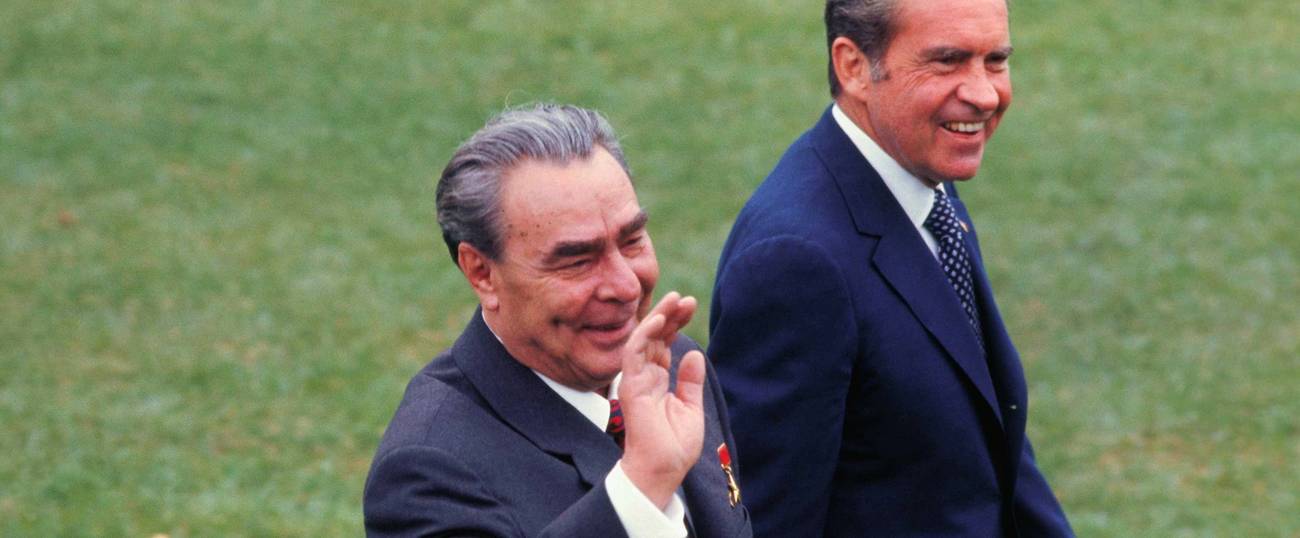

I point to the election of 1972. It might be supposed that, faced with a choice between Richard Nixon and George McGovern, the Russians—the Soviets, that is—must surely have preferred McGovern. But they preferred Nixon, and the reasons ought to be obvious. Nixon in his first term had come out for détente, which was a breakthrough in the Cold War. Détente amounted to a deal, which applied to both sides. On the American side, Nixon wanted the Soviets to agree to abandon their efforts to revolutionize the world and especially Western Europe (though of course Nixon recognized that the Soviet Union had non-revolutionary interests, which it could legitimately pursue, nor did anyone expect the Soviets to give up on their political rhetoric). And, in exchange for such an agreement, Nixon agreed to abandon the revolutionary project that was America’s—namely, the effort to revolutionize the Soviet Union and the East Bloc (though no one expected America to give up on its own rhetoric).

In short, neither side would try to overthrow the other, and, as a result, they would get along better. Such was the meaning of détente. Nixon showed himself to be faithful to this deal, even when fidelity was bound to be costly to him politically at home. A famous example: In 1975, Alexander I. Solzhenitsyn arrived in the United States, bearing his literary testimony against the crimes of Communism. Nixon, on Kissinger’s advice, declined to receive him. In Washington, D.C., it was the AFL-CIO that received Solzhenitsyn. The AFL-CIO leaders were classic Cold Warriors, and they had been hoping to overthrow the Soviets for many years, and they correctly recognized that Solzhenitsyn and his literary works might contribute to doing so. By receiving Solzhenitsyn, the AFL-CIO delivered a sharp punch in the nose to Nixon, which he must have hated. But he understood that, if he shook Solzhenitsyn’s hand or welcomed him to the White House, the Soviets would feel betrayed. So he refrained. He was a man you could count on.

And the Soviets—did they, too, display a fidelity to the implicit deal? Did they go out of their way to make sure that Nixon, too, would not feel betrayed? The minor-party history of the 1972 election tells the story.

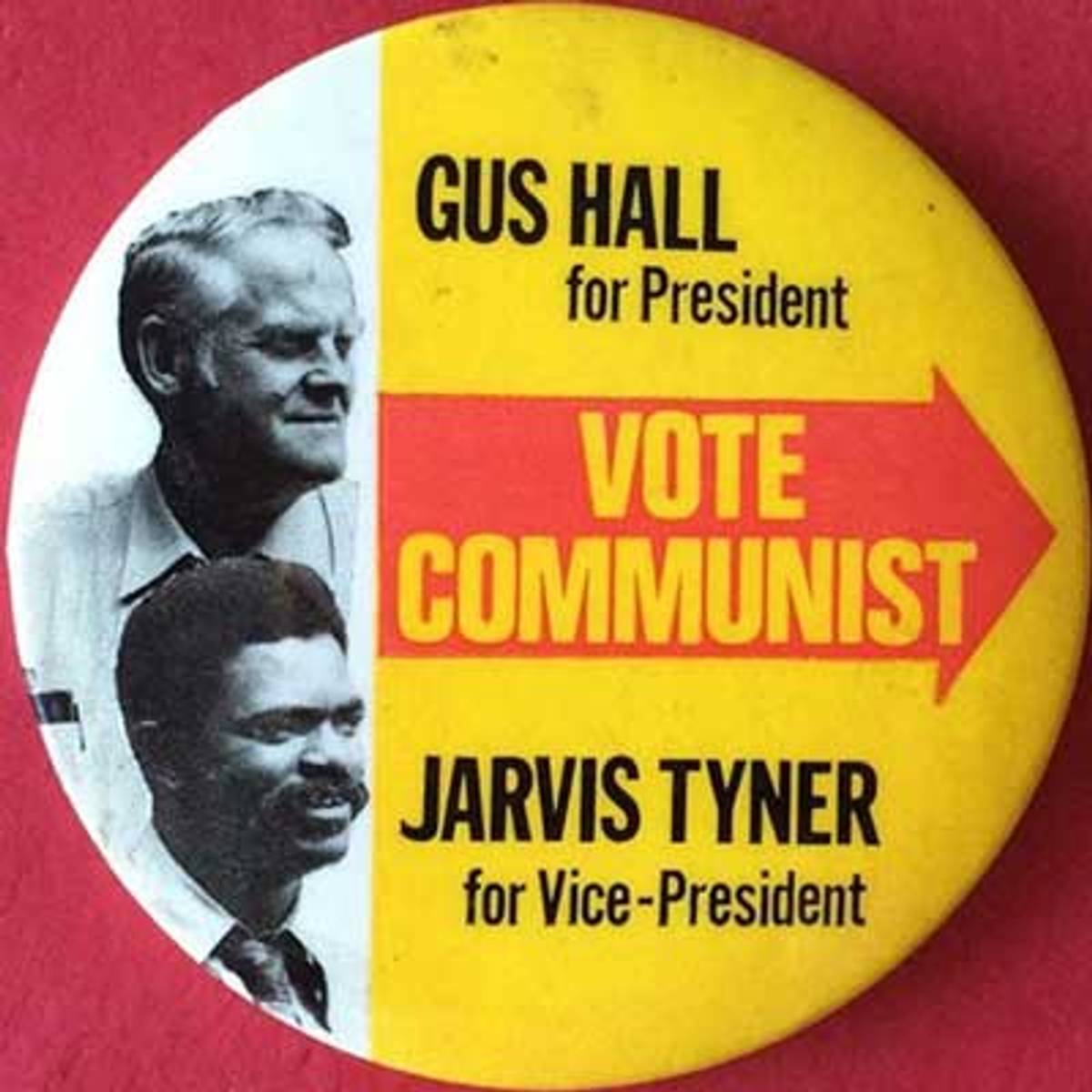

It is sometimes forgotten that, during the entire history of the Soviet Union, the Soviets possessed a more-or-less above-ground mechanism for intervening in American affairs, which was the Communist Party USA. The Communist Party proved to be less than successful at performing its interventions, apart from a few moments in the 1930s and ’40s, which is why the party’s machinations have faded from the American memory. But the Soviets, who may not have been too shrewd, went on believing in the Communist Party and its political prospects, even so—went on believing out of Communist doctrine, or perhaps because the party’s General Secretary for many years was Gus Hall, who spent a portion of every year in Moscow, where he proved to be adroit at promoting his own party and its reputation and interests. And the Soviets acted on their belief. Their subsidies to the Communist Party USA were greater than to any other party around the world, except the French Communist Party—subsidies that, in the 1980s, continued to flow at a rate of some two million dollars or more a year, all the way until Communism’s crisis began to hit, which was in 1987.

Nixon’s re-election, then. The Nixon campaign put the Communist Party USA in the same embarrassing bind that Nixon himself was put in by Solzhenitsyn, except from the other side. The American Communists had supported the Democratic Party in 1964 and 1968, just as you might suppose from Kalugin’s comments. But, in 1972, after Nixon had devoted his first term to promoting détente, the Communist leaders could hardly turn to their generous backers in the Soviet Union and explain that Communists in America were going to fight tooth and nail to get Nixon defeated. On the other hand, the Communist Party USA would have looked ridiculous in openly coming out for the Republican Party. What to do? The Communist Party ran its own ticket, with Gen-Sec Hall as candidate for president. The idea was to take the wind out of McGovern’s sails, not just by depriving the Democrats of the Communist electorate, which was maybe not too vast, but by depriving the Democrats of any advantage to be gained from the Communist Party’s apparatus and press, which, on a tiny scale here and there around the country, not always under the name of Communism, did count for something.

Then again, the Communist Party also decided to relax its own party discipline, in order to give party members and supporters the freedom to campaign for McGovern and the Democratic Party, if they wished to do so. That was a necessary move because, even if the Communist Party was a shadow of its old self from the 1930s and ’40s, a few pockets of the labor movement remained loyal—the West Coast longshoremen’s union, notably, together with occasional factions of other unions. The party was not going to drive those people away. The position, then, was pro-Gus Hall, conceived as a pro-Nixon maneuver, with provision to allow Communists in the labor movement to preserve their reputations. I have no idea whether the Soviets did anything else or anything shadier on Nixon’s behalf. But it ought to be obvious that, either way, someone in Moscow—some committee or desk with a sense of how handsome were the subsidies to Gen-Sec Hall and his party—must have devoted a lot of effort to assessing the complexities of the 1972 election, and a lot of effort to figuring out how best to deploy the Soviet assets, such as they were.

Is there anything in these events from long ago that bears on our present situation? I think Kissinger’s name should remind us that yesterday and today are not very far apart. Kissinger himself appears to have no influence at all in the Trump administration, even if he had lunch with Rex Tillerson. Even so, Donald Trump has plainly been offering détente to the Russian Federation, perhaps in a cruder fashion than Nixon and Kissinger. Vladimir Putin has had every reason to respond by deploying his own assets in order to manipulate the American scene as best they can. Being an old KGB man, Putin must have appreciated that, in Moscow, there is an ancient and accumulated knowledge of how to conduct such manipulations in the United States. The accumulated knowledge is subtle. The knowledge teaches that sometimes it is fully in Russia’s interest to favor the Republicans, and not the Democrats, whenever the Republican Party has gone into its Kissingerian phase: a policy with a precedent from 1972. And, lo, having been at it since 1919, the Russian specialists at manipulating American politics have, at long last, scored a bull’s-eye—a matter of sheer luck, but, then again, practice makes perfect.

***

Read more of Paul Berman’s political and cultural analyses for Tablet magazine here.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.