Magic Number

Coach Red Holzman led the Knicks to their only championships and an auspicious 613 wins

In the rafters of Madison Square Garden, high above the court, are the supersize jerseys that commemorate the retired numbers of the New York Knicks and the New York Rangers. There’s the jersey of Mark Messier, one of hockey’s all-time superstars, and his 11; there is basketball center Patrick Ewing and his 33. But most of the Knicks represented played on the same early-1970s teams: Dick Barnett (12), Bill Bradley (24), Dave DeBusschere (22), Walt Frazier (10), Earl Monroe (15), Willis Reed (19). Pennants celebrating the 1970 and 1973 NBA championships they won together hang nearby.

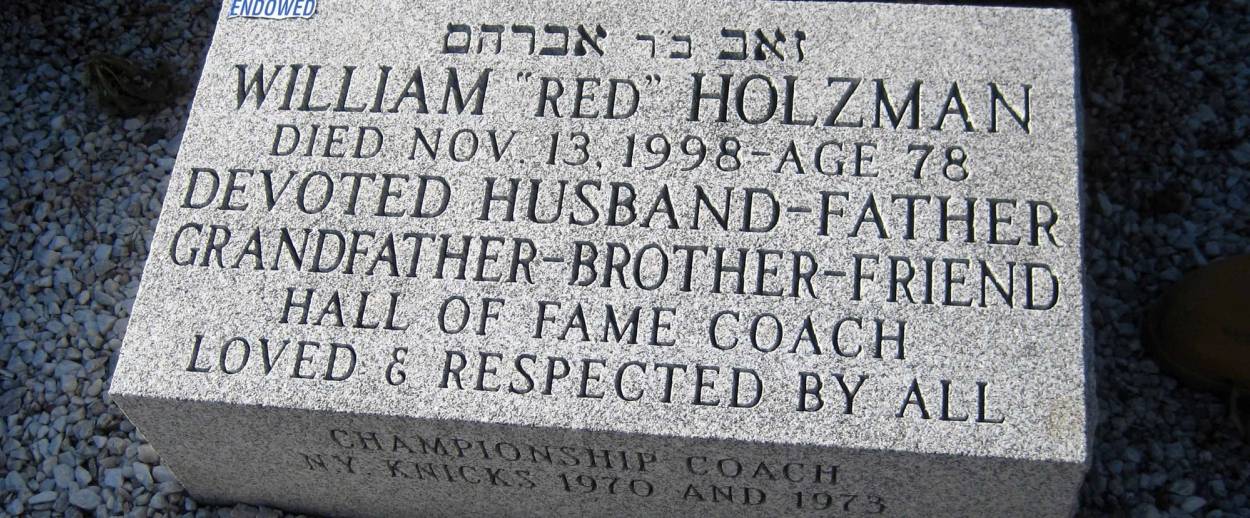

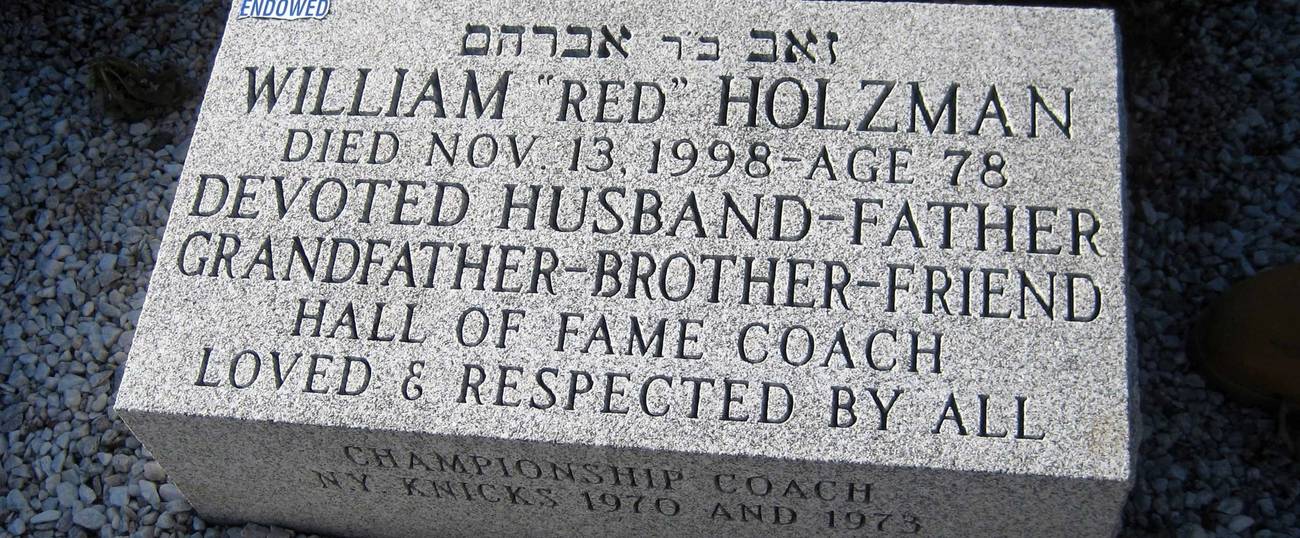

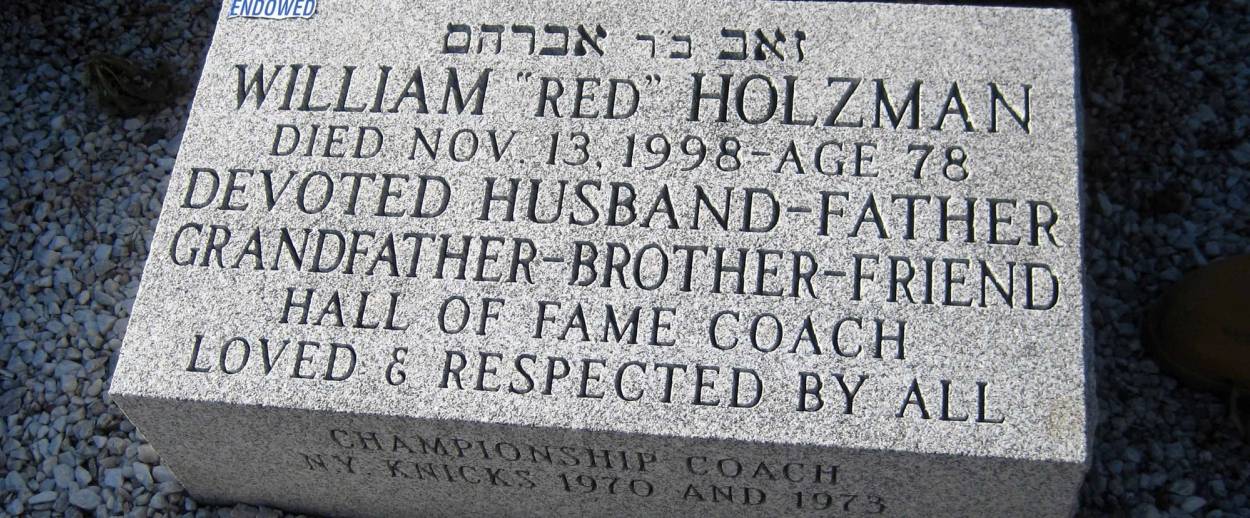

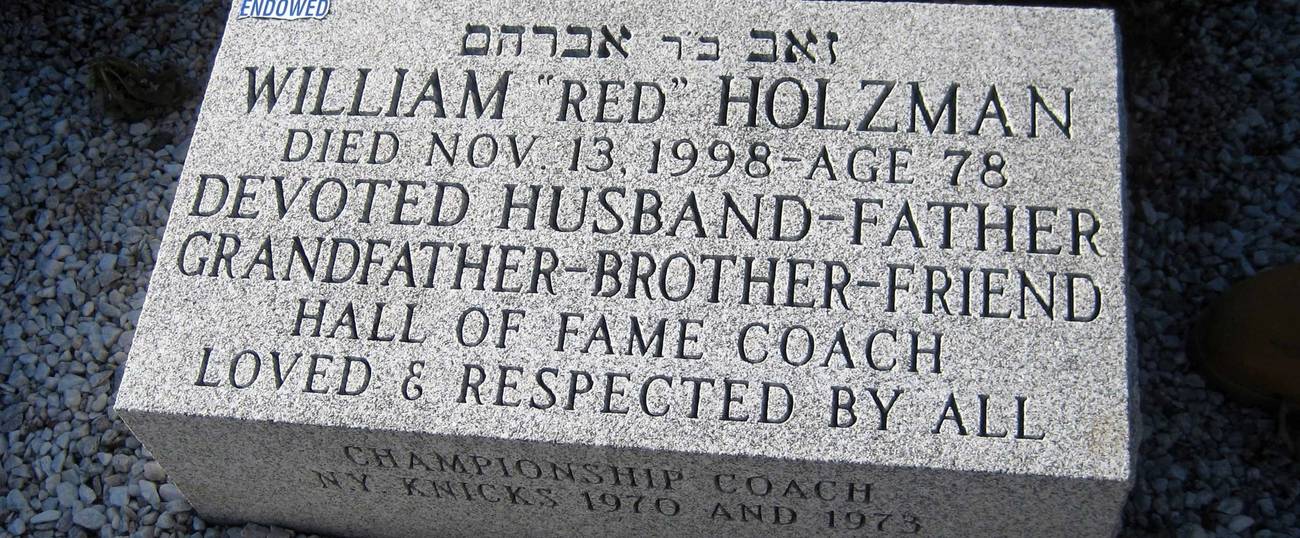

Finally, there is a jersey for the head coach of those storied Knicks squads. Everyone knew William Holzman as “Red” on account of his hair—except for his Yiddish-speaking family, in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, which called him “Roita.” Holzman, who died in 1998, had no number to retire so instead, on his jersey, which has looked down on the Knicks as they have tried and failed to add a third championship to the two he oversaw, is the number of wins Holzman achieved as Knicks coach: 613.

Six hundred and thirteen is also, of course, the number of mitzvot, or commandments, in the Hebrew Bible. Bill Bradley, who spent a decade as Holzman’s small forward before becoming a Democratic senator from New Jersey and then running against Al Gore in the 2000 presidential primary, laughs for several seconds when I explain this. He is ready with the magic number almost before I am done asking about it: “Six thirteen,” he says, in his familiar stentorian baritone, previously unaware, he says, of the number’s significance. He is on the phone, standing in the security line at JFK Airport, and I imagine those around him wondering what he finds so funny. “He was the key to the Knicks’ success. Obviously the players came together with the mesh of talents and personalities. They had to be guided by him,” Bradley says. “He was very clear about what he expected, he had a few simple rules everyone had to follow. Help on defense, on offense hit the open man.”

Holzman, too, had no idea initially of the number’s importance, according to Ira Berkow, the Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times sportswriter, who writes movingly of his friendship with Holzman, cemented by their shared Romanian Jewish heritage, in a memoir, Full Swing. A rabbi informed Holzman of the coincidence sometime before the jersey was raised, in 1990. “He was without question a cultural Jew,” Berkow tells me. “When he learned about the 613’s Jewish symbolism, he was very pleased.”

“I think that he was happy for the coincidence,” says Gail Papelian, Holzman’s only child. “It was meaningful to him.” Papelian and her parents lived in a modest house in Cedarhurst, New York, one of Long Island’s Five Towns. (Red and Sylvia Holzman were married for 55 years; she died the same year as her husband.) Papelian recalls that her father would fast on Yom Kippur but rarely attended synagogue. “I think that the number is something he was very proud of,” she says.

The number 613 is something Knicks fans should be proud of, too, especially as they attempt to cheer for a team that has not been competitive for a decade. A little ersatz gematria is in order: Holzman won his 613 regular-season games over roughly 13 seasons (he began midway through the 1967-1968 season and coached through 1981-1982, taking a break for a year). If you count backward from today, though, you would have to cover more than 17 Knicks seasons to total 613 wins. And if the Knicks repeated this past year’s pitiful win count of 29 every year, it would take them more than 21 seasons to reach Holzman’s record. All in all, Holzman retired with what at the time was the second-most wins of any NBA head coach.

Holzman’s Knicks teams were notable—remain notable—for the way they played as teams. Berkow credits Holzman’s great defenses, his brilliant aptitude for designing mismatches with the opposing squad, and his ability as a communicator.

Berkow says the great Bob Pettit, who won the NBA’s first MVP award, liked to tell a story from when Holzman coached him on the Milwaukee and then St. Louis Hawks in the early 1950s. After a bad first half one night, Holzman gathered his team in the locker room, opened his wallet, and took out a picture of Gail Papelian. “She’s a very cute girl,” Holzman apparently told his players. “I’d like her to grow up to be a healthy young woman, but if you keep playing like this, I’m gonna be fired and not be able to feed her.” Holzman, incidentally, moved Pettit from center, the position he played at Louisiana State, to power forward.

Holzman was the chief acolyte of Nat Holman, who had coached him at City College, where Holzman played guard. But Holzman is better known for his own acolytes: Several former players went on to become head coaches and general managers. Among them is Phil Jackson, who has won, in addition to two championships as a back-up forward and center on Holzman’s Knicks, 10 as head coach of the Chicago Bulls and the Los Angeles Lakers. Jackson’s Lakers are again in the spotlight: Their best-of-seven series with the Boston Celtics for the championship begins tonight. If the Lakers win, it’ll be Jackson’s 13th championship. His current 12 is already a record, as are his current 10 as head coach.

The only other head coach who comes close, with nine championships, is the Celtics’ legendary Red Auerbach (another Jewish Red). The NBA’s Coach of the Year award is named after him. “But for me, it’s the Red Holzman Award,” Jackson said in 1996, when he won the award leading Michael Jordan and the Bulls. “It was Red who taught me what coaching basketball was all about.”

Maybe Holzman’s greatest coaching attribute—and this is what folks invariably say about Jackson, too—was his willingness to treat his players as adults. Walt “Clyde” Frazier—Holzman’s starting point guard, who is now the Knicks’ color commentator on TV—recalls a long bus ride back from a loss against Philadelphia. “We were in the middle of a losing streak,” Frazier remembers. Holzman “said he wanted me to sit next to him. I knew what that meant.”

“ ‘What’s wrong with you, Frazier?’ ” he asked. “And then he said, ‘I believe in you, and we’re going to keep playing you.’ ”

Frazier, who had Holzman introduce him at his 1987 Hall of Fame induction ceremony, is particularly forthcoming on the subject of Holzman and race. “I grew up under the oppression of segregation,” he tells me. “My grandfather said that if you respect someone, then nine times out of 10 they will respect you. And that’s what Red was.”

Adds Bradley: “He never criticized a player, and he would rarely say much about a player. I think that was a very self-effacing way to lead.” Plus, “off the court, there was only one rule, and that was: The hotel bar belonged to him.”

“It’s good to talk about him,” Frazier told me, unprompted. “He was a great man.” Bradley thanked me for informing him about the 613 connection. And I could almost hear Charlie Papelian, Holzman’s son-in-law, grow misty-eyed over the phone as he remembered “a good coach, a better father-in-law, and an even better friend.”

But perhaps it is Knicks fans who are most in need of Holzman’s memory. Forty years ago, their team was the world champion, twice. Since then, they have been plagued by the sort of mismanagement that makes even rivals sympathetic, punctuated by spurts of greatness that have left them short of a third title.

Among the Knicks’ still-loyal fans are Gail and Charlie Papelian, season ticket-holders. “Like any other Knicks fan over the last 10 years, we’re looking for better things to come,” Charlie Papelian tells me. “It would be great to see LeBron come to New York. But, the overall concept still comes back to team. Team-winning basketball.”

The team that most plays that type of basketball right now, according to Gail Papelian, are the Celtics.

“I like the team concept of the Celtics a lot,” she tells me.

Charlie Papelian coughs: “Currently.”

She confirms that is what she meant. “Currently,” she says. “Not in the old days.”

Marc Tracy is a staff writer at The New Republic, and was previously a staff writer at Tablet. He tweets @marcatracy.