Burning Bush

The mass uprising in Egypt that seems set to overthrow the Mubarak regime is the latest test of George W. Bush’s Freedom Agenda. The U.S. and Israel are hoping it works out better than the previous three.

Administrations are overtaken by events all the time. And so President Barack Obama may be forgiven for his strange press conference on Egypt last week, in which he didn’t seem to know whether to praise Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, Washington’s longtime ally, or side with the masses whom the U.S. president has been courting since his 2009 Cairo speech. And yet the fact remains that the Obama Administration has no strategy to deal with events still unfolding in Egypt, nor even a worldview on which to base one. His predecessor, for all his flaws, did have a strategy. What we’ve been watching on the streets of Egypt this past week is the fourth test of George W. Bush’s Freedom Agenda.

The Bush White House believed that the problem with the Arabic-speaking Middle East was in the nature of repressive Arab regimes: In this view, Sept. 11 was the product of a political culture that had been strangled by its rulers, allowing their people no form of political expression except extremism. Deposing these regimes would unleash the native political energies of Arab peoples, went the argument, who would turn their attention away from anti-American and anti-Israeli sentiments to the thoughtful participatory governance of their own societies. Accordingly, promoting democracy in the region was not only good for the Arabs, but also in America’s national interest. The first test for this Freedom Agenda was Iraq, followed by Lebanon and then the Palestinian Authority. Egypt is the fourth test—and the most consequential yet, for Cairo is the linchpin of Washington’s Middle East strategy.

Egypt was once commonly referred to as leader of the Arab world—an honorific denoting Egypt’s leadership in the arts, intellectual life, and media, as well as its enormous population of 80 million. And unlike other Arab states—Syria, say, or Saudi Arabia—Egypt has a real history and identity dating back thousands of years. Primarily, however, “leader of the Arab world” referred to Cairo’s political status, specifically its role in the wars against Israel.

When Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s second president, was in office, all his political capital rested on the fact that Egypt, unlike U.S. allies Saudi Arabia and Jordan, clamored for war with the Zionist entity. When Anwar Sadat, his successor, brought Egypt from the Soviet to the American side after the 1973 war, it represented a Cold War victory for Washington that paid huge strategic dividends. However, it is one of the paradoxes of U.S. Middle East policy that by signing a peace treaty with Jerusalem, Sadat took Cairo out of the front-line camp and thereby weakened the regional prestige of a key American ally. Of course that treaty also put Sadat in the crosshairs of the Islamists, who killed him at Cairo stadium in 1981, with Mubarak beside him on the reviewing stand.

That peace has not only been good for the United States, securing our hegemony in the Eastern Mediterranean, but also of course for Israel. It is that treaty with Cairo that allows Israel the relative luxury to worry primarily about a Persian adversary far from its borders and two terrorist groups, Hamas and Hezbollah. The prospect of Egypt, with a large U.S.-trained and equipped army, air force, and navy, once again becoming “leader of the Arab world” is a nightmare for Israel’s leaders.

The U.S.-backed order in the Middle East is founded entirely on Cairo’s position as an ally—and on keeping the peace, as Mubarak has. If Egypt moves out of the American fold, it might well align itself with Iran. Mubarak has known well enough to fear the Islamic Republic—a street in Tehran is named after Sadat’s assassin. Or perhaps it would challenge the Iranians, in the way regional competition has worked since 1948—by seeing who can pose the greatest threat to Israel. Therefore, this fourth test of the freedom agenda could not be more important.

***

Unfortunately, after the first three runs, it’s hard to be optimistic this time. What we’ve seen so far is that the political energies unleashed by the Freedom Agenda are not democratic but tribal, sectarian, and violent. In Gaza, the Palestinian electorate voted for Hamas. In Lebanon, while the majority voted for the pro-democracy March 14 movement, Hezbollah still won power in government even as it embarked on a bloody campaign culminating last week in the party’s takeover of the state. After U.S. forces brought down Saddam Hussein, Iraqis turned on each other, fueled by more than a thousand years of a sectarian rage that was further aggravated by Saddam as Sunnis and Shiites shed blood at a clip typically associated with the grislier sectors of central Africa.

It is true that Egypt is not Iraq. And yet as many seem to have forgotten, only a month ago Islamist militants attacked a church in Alexandria, killing 23 Coptic Christians. To be sure, many Muslims rallied to defend their Christian neighbors, and today there are Christians in the street alongside the Muslim majority, but anyone who thinks sectarian tensions are simply the fault of “extremists,” or the Mubarak regime’s inability to protect Christians, is missing the point: The execution of minorities strongly suggests that a society might not be ready for democracy.

The relevant minority here are the liberals and democrats, for they do indeed exist and Egypt is the historical capital of Arab liberalism, from the novelist Taha Hussein to the journalist Farag Foda. Today there are a number of bloggers, intellectuals, and journalists, like the playwright Ali Salem and Hala Mustafa, editor of the political journal Dimoqratiya (Democracy), who keep the liberal flame alive. The former wrote a book about his trip to Israel and the latter met with the Israeli ambassador, and both were punished for it and ostracized by their colleagues. This is an indication not only of their lack of popularity but also the temperament of Egyptian intellectual culture: illiberal and populist—in other words, undemocratic.

There is some truth to the idea that Mubarak has choked off his liberal opposition, leaving only the Muslim Brotherhood to challenge him, but arguably the Egyptian liberal movement came to an end with the 1926 publication of Taha Hussein’s work on pre-Islamic poetry, which dealt with the historical and literary foundations of Islam. Under pressure from the religious authorities and death threats from Islamists, Hussein removed the passages deemed offensive, and the precedent was set: Men with guns make the rules, which liberals must abide by or be killed. Nonetheless, more than half a century later, Foda challenged the Islamists, and they reminded him how precarious liberalism is in Egypt by gunning him down in a Cairo street in 1992.

The Islamists, represented now by the mainstream Muslim Brotherhood, are one of only two political institutions that would survive Mubarak’s downfall; the other is the military. Indeed, Egypt has been run by military rulers more often than not—from the Muslim conqueror of Egypt Amr ibn al-‘As to the Albanian soldier Mohamed Ali, whose dynasty fell to Nasser’s Free Officers in a 1952 coup. Mubarak’s son Gamal’s presidency would have represented something like a coup d’etat against the military, which is why they got him out and chief of military intelligence Omar Suleiman was named vice president, making him Mubarak’s official successor. The awful irony is that Gamal and his gang of young financiers and businessmen probably represented Egypt’s best chance to move away from military rule. At least this is what much of the Washington policy establishment believed, with the hope of getting Gamal to pick up the pace of political reform to match the country’s notable economic reform. If Mubarak goes down, the security forces, the military and the Islamists, including the Muslim Brotherhood, will fight each other, or cut a deal, or both.

***

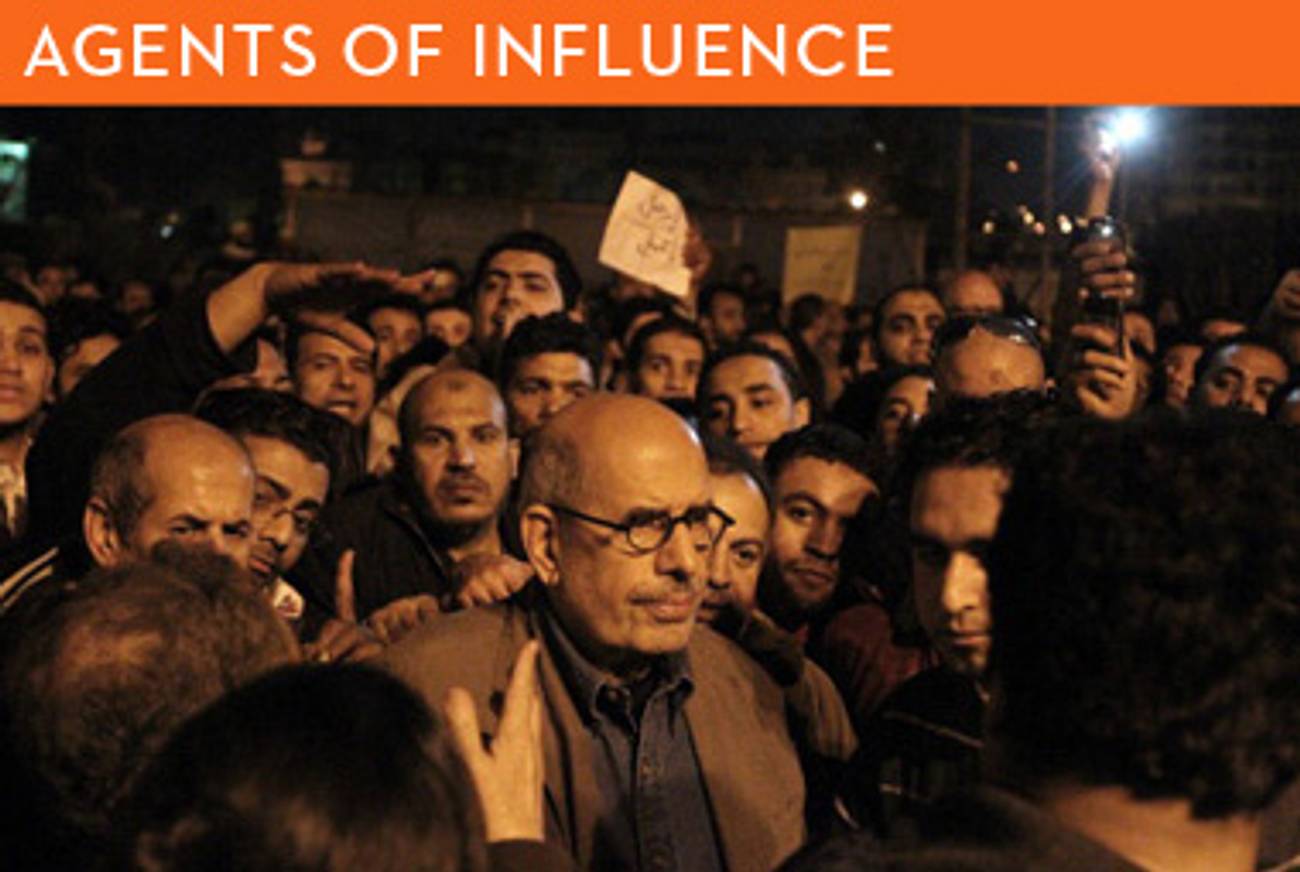

Consider the other options. The United States wants national dialogue, which seems to include Mohamed ElBaradei. By virtue of his name recognition alone, the former IAEA head has been hailed by the Western press as one of the leaders of the democratic opposition. However, at the IAEA this so-called reformer distorted his inspectors’ reports on Iran and effectively paved the way for the Islamic Republic’s march toward a nuclear bomb. Now the Muslim Brotherhood has named him as their interlocutor. In other words, ElBaradei is nothing other than a shill for Islamists.

There’s also Ayman Nour, leader of the liberal Ghad (Tomorrow) party, who finished third in the last presidential elections before he was jailed on trumped-up charges. Then there’s Saad Eddine Ibrahim, the Arab world’s most famous democratic-rights activist, who was also imprisoned by Mubarak and is now living abroad in the United States. During Hezbollah’s 2006 war with Israel, Ibrahim came down on the side of the Lebanese militia. Ibrahim’s posture was hardly surprising given that his onetime jailer despised Hezbollah. But it is odd that a democratic advocate should applaud war with Israel, a country with whom Cairo has had a peace treaty for more than 30 years.

Maybe this should be one of the tests for Egypt’s democrats in the streets: Where do you stand on Israel? If they are really democrats, or just pragmatists, the young among them protesting for higher pay would answer that warmer relations with an advanced, European-style economy—like, say, Israel’s—would provide jobs for the millions of Egypt’s unemployed. Of course that is not the answer you’re going to get from the young men now filling the streets of Cairo. Or forget about Israel and ask them instead about Hezbollah. Do they support the Islamic resistance? Of course they do, because Egypt’s most famous democrat Saad Eddine Ibrahim supports Hezbollah, the outfit that has turned the remnants of Lebanese democracy on its head while killing its opponents.

No doubt there are real liberals and democrats in Egypt, and some may even be in the streets today, but they are not going to come out on top. In part that is because the United States is not going to help them. Indeed, Washington showed how seriously it takes Arab liberals and democrats two weeks ago when it watched silently from the sidelines as Hezbollah toppled Saad Hariri’s government. Plenty of Arabs hoping for a democratic Lebanon died over the last five years since the assassination of Rafik Hariri, and it is important to note that the million-plus Lebanese who went to the streets on March 14, 2005 demonstrated peacefully, unlike the Egyptians, and all the destruction and violence was caused by Hezbollah and its pro-Syrian allies.

That the United States will not come to the aid of its liberal allies, or strengthen the moderate Muslims against the extremists, is one reason why the Freedom Agenda is not going to work, at least not right now. The underlying reason then is Arab political culture, where real democrats and genuine liberals do not stand a chance against the men with guns.

Lee Smith is the author of The Consequences of Syria.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).