“Howl” and the Obscenity Trial

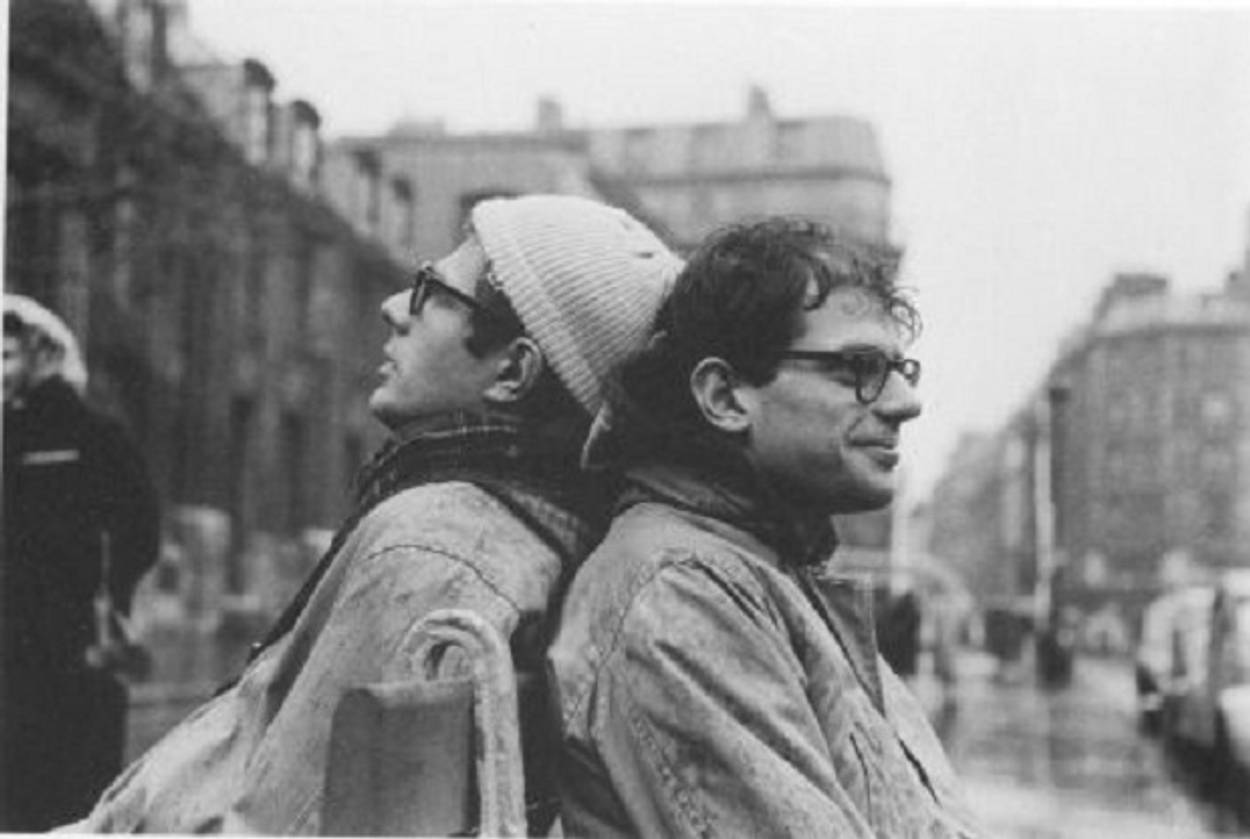

Allen Ginsberg’s date with history

On this date in 1957, California Judge Clayton W. Horn ruled that Allen Ginsberg’s poem “Howl” was not obscene. The much-publicized trial, which made its way into magazines like Time and Life, famously featured the testimony of nine literary experts who spoke out in favor of the poem’s merits.

The trouble began earlier that year on June 3–Ginsberg’s birthday–when police arrested a bookseller at the City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco for selling the book Howl and Other Poems to an undercover officer. (In another high profile incident that year, 520 copies of the book containing the poem were confiscated while being imported from London.)

Despite the poem’s references to sex (heterosexual and homosexual), drugs (illicit), and rock n’ roll (obviously), which were still controversial at the time, Horn declared the poem to have “redeeming social importance.” Since then, countless writers, poets, filmmakers, and stoned graduate students have created their own encomiums. Here’s Fred Kaplan who, as far as I know, only fits in one of the above-listed groups. (James Franco, who starred in the film Howl may be all four.)

It was an anguished protest, literally a howl, against the era’s soul-crushing conformism and a hymn to the holiness of everything about the human body and mind, splashed in verse that breaks free from standard meter but speaks instead in the long lines and jangling rhythm of natural breath and conversation, a style inspired by the expressive poets who went ignored in the ivory towers of high modernism—Whitman, Blake, Rimbaud *—fused with the urban syncopation of the bebop jazz that Ginsberg and his pal, Jack Kerouac, went to hear in the clubs of Harlem while they were students at Columbia in the mid-1940s.

Writing about the (very impressive) collected letters of Allen Ginsberg, our intrepid literary critic Adam Kirsch had this to say about Ginsberg and his most famous poem.

Ginsberg was much more polarizing than most poets, even most avant-garde poets, because he did not see himself as simply an artist. While he was very learned about English literature—not for nothing was he a favorite student of Lionel Trilling and Mark Van Doren at Columbia in the 1940s—he did not want his writing to be approached with the discriminating, hypothetical intelligence we ordinarily bring to literature. His writing was, instead, a kind of speech, directed not to the “poetry reader” but to the whole mind and soul. He was a prophet who used verse to chastise and exhort his people, as in the famous lines from “Howl”:

Moloch whose love is endless oil and stone! Moloch whose soul is electricity and banks! Moloch whose poverty is the specter of genius! Moloch whose fate is a cloud of sexless hydrogen! Moloch whose name is the mind!

A few weeks ago, Allen Lowe, writing for The Scroll’s poetry feature Scroll Verse, added “Hell: A Jew in Maine” to the discourse–an update of the poem.

Related: Dear America [Tablet]

How “Howl” Changed the World [Slate]

Adam Chandler was previously a staff writer at Tablet. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Atlantic, Slate, Esquire, New York, and elsewhere. He tweets @allmychandler.