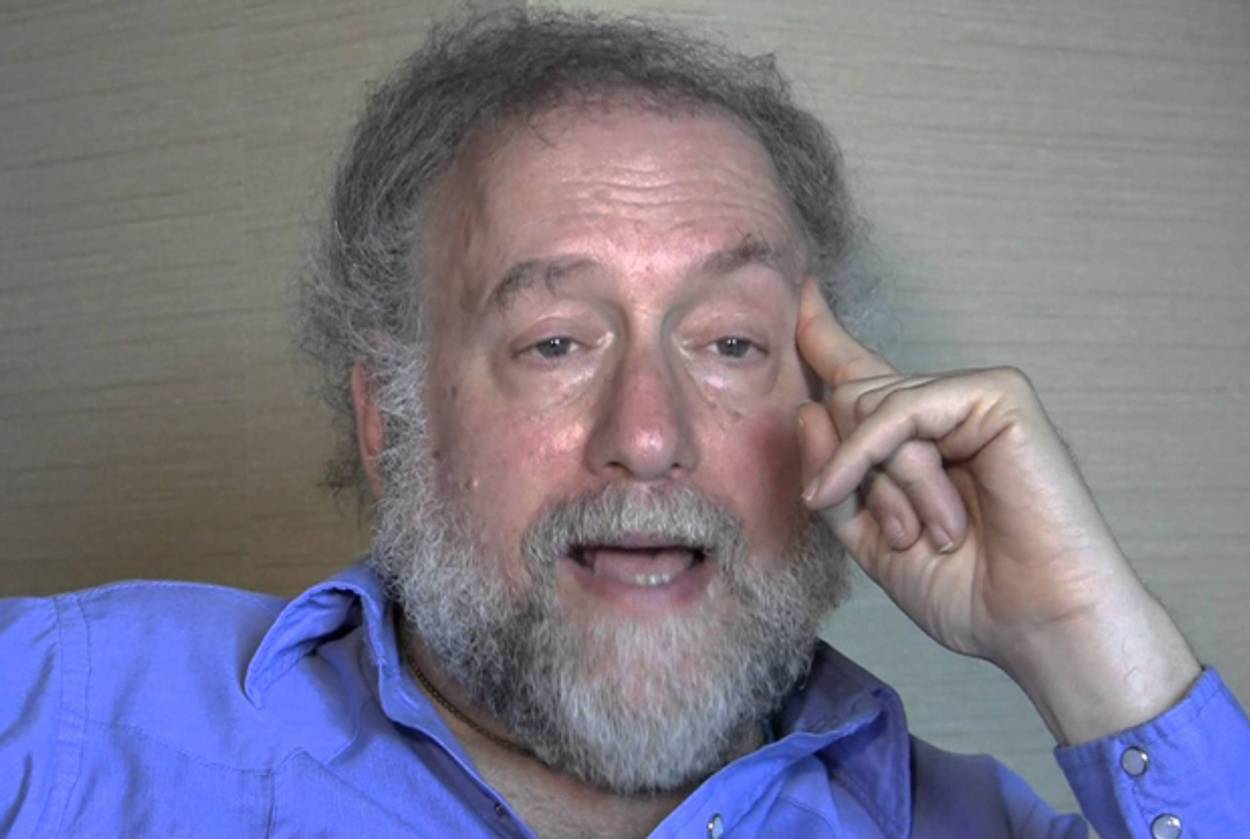

Learning from Barry Rubin, A Lifelong Teacher

The writer, whose new book was reviewed in Tablet today, died last night at 64

This morning Tablet reviewed Nazis, Islamists, and the Making of the Modern Middle East, a new book by Barry Rubin and Wolfgang Schwanitz. Although it’s a challenging and critical take, it’s also, I’d argue, precisely the sort of engagement with his work that Barry most relished, a real debate, an argument with ideas, history, and the future and real lives at stake. Sadly, Barry is not around to partake in it. He died last night at the age of 64 after an 18-month struggle with cancer.

Barry was my friend and teacher, a role I suspect that—after husband to his wonderful wife Judy and father to his two spectacular children, Gabriella and Daniel—he relished above all others, including that of author, analyst, and historian. He wrote dozens of books focusing on the Middle East, from Israel and Turkey to Egypt and Iran, as well as other subjects, and used his deep historical knowledge of the region to analyze and explain current phenomena, but I think it was teaching that truly moved him. He was expansive. Like most of his pupils, I never studied with him formally at any of the American or Israeli universities he taught at over the years. Rather, learning from Barry was through phone conversations, or email, or best yet over a meal or a bottle of wine at his home in Tel Aviv or his other home in Washington or some small café or restaurant when he’d start some conversation on the Middle East lamenting not only the state of affairs but also the popular understanding of the state of affairs. It was important to get it right because there was a lot at stake—like the lives of real people, not just Israelis but Arabs as well, and millions of other Middle Easterners.

Therefore, Barry had friends and students around the region, Arabs and Israelis, Turks and Iranians, and all of the countless minorities that compose the modern Middle East, which was not only the focus of his work but also his home, an often hard place. But Barry was open to and curious about difficult things. He loved model trains, and part of his collection filled the first floor of his home in Tel Aviv. He loved the American south and frequently visited there to participate in historical re-enactments of the Civil War. He loved Israel and being Israeli. He also loved the United States, but was worried for us that we were losing something, our seriousness maybe. He loved Washington, too, where he was born and where he’d lived and worked for years on Capitol Hill before making aliyah. He showed me around the neighborhood I lived in, the neighborhood he grew up in, and unfolded its untold history, which was his way.

He was expansive, which is to say that Barry was a student, too. He revered his teachers, the great elders who’d preceded him, like Walter Laqueur, and the generations destined to follow, the students he’d learned from—or perhaps just forgotten he’d taught. One insight from a student, one knock on the door of wisdom, and Barry’s eyes light up, his mouth opens in an expression of near astonishment. “You’re right,” Barry would say. “You are absolutely right.” But you taught me that, Barry—the student would reply. “You have a good memory,” he’d respond.

It was all one coherent whole for Barry Rubin, history and the future, the generations past and those coming, which is to say that our teacher and friend who died yesterday will never wholly die.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).