FBI Burglars Break Their Silence in New Film

Activists behind 1971 break-in that exposed government surveillance tell all

Earlier this year, we reported on the newly-uncovered story of eight antiwar activists who broke into a small FBI office outside of Philadelphia on March 8, 1971. Led by a soft-spoken Jewish physics professor at Haverford College named William Davidon, the conspirators stole hundreds of secret files that exposed the FBI’s illegal efforts to intimidate civil rights activists and Americans protesting the Vietnam War.

Now, in a new documentary called 1971, the members of the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI—the name the activists gave themselves—are speaking out about their actions for the first time on film.

The story unfolds through a combination of interviews, primary documents from the break-in and subsequent investigation, and news coverage of the burglary. Tapping into contemporary concerns about governmental abuses of power and invasions of privacy, the film frames the 1971 events that took place in the Philadelphia suburb of Media as the precursor to the Pentagon Papers, WikiLeaks, and Edward Snowden’s NSA revelations. Testimonials follow from five key characters: married couple John and Bonnie Raines, cab driver Keith Forsyth, social worker Bob Williamson, and Bill Davidon.

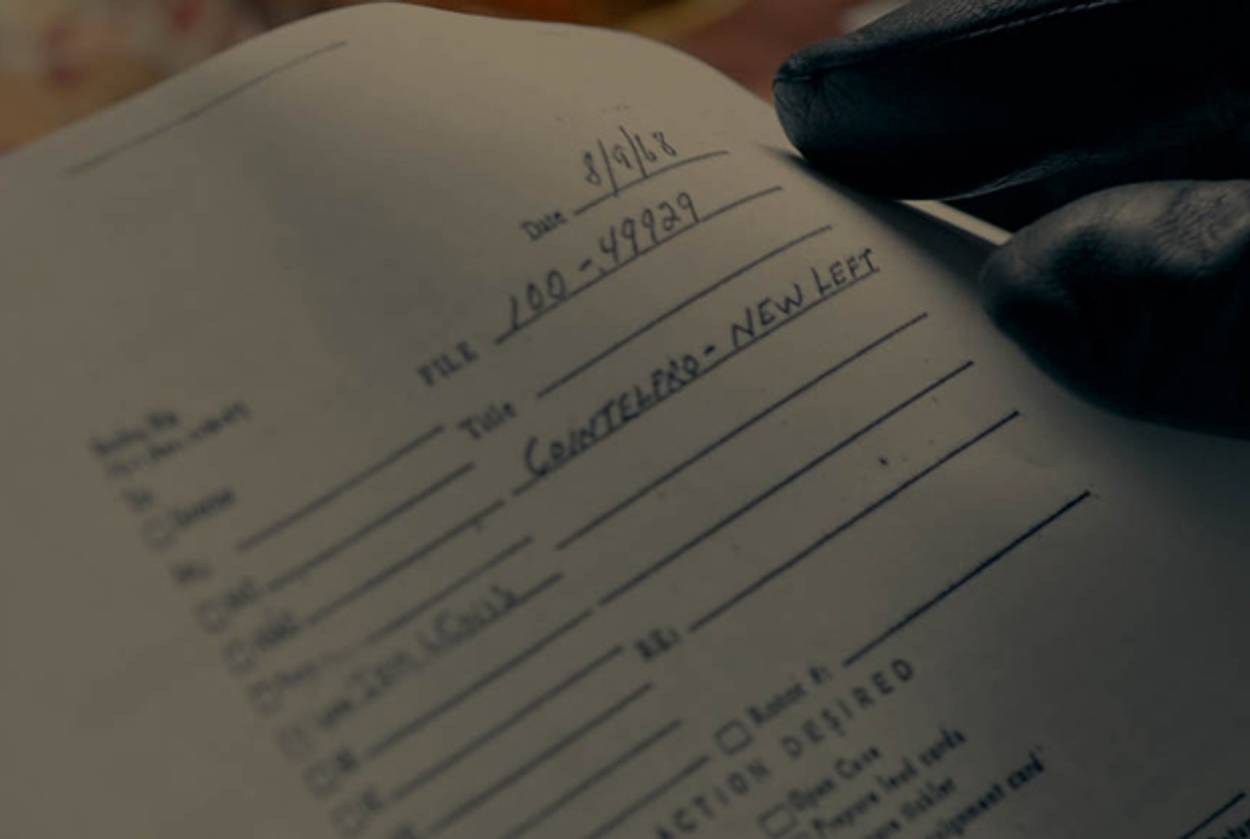

The group, hand-picked by Davidon, describes months of training as amateur burglars. Wearing gloves at all times, they successfully executed the break-in, filled suitcases with files, and meticulously read through all the stolen pages. Then, they mailed selected documents to the press, and chaos ensued. Journalist Betty Medsger—whose book brought the drama to the American public in January—broke the story in the Washington Post, fueling immediate national outrage at the idea of FBI-run domestic surveillance of U.S. citizens. After a lengthy legal battle, 50,000 documents reveal that FBI director J. Edgar Hoover was in fact spearheading a covert and entirely illegal surveillance program called COINTELPRO.

The team’s revelations that Hoover had ordered phone operators on college campuses and U.S. postal employees to intercept and report citizens’ transmissions was more than the robbers had expected to uncover. The film ends with members of the Citzens’ Commission explaining why they decided to break their silence after 40 years, but with questions of government oversight and citizens’ rights to privacy still very much on American minds, this story’s real finale has not yet played out.

1971 premieres at the Tribeca Film Festival on April 18th.

Lily Wilf is an editorial intern at Tablet.