Did ‘Close Encounters’ Herald the Advent of a New Religion?

Spielberg’s 1977 sci-fi epic is loaded with portents, but what do they mean?

You don’t need to strain too hard to find the biblical imagery in Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind. You don’t even need to see the movie. The poster alone—a mountain clouded with smoke and bathed in heavenly light—is enough to signal that something big is about to be revealed.

In the movie itself, the allusions to Mount Sinai are even more direct. When we first meet our protagonist, electrical lineman Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss), he’s just given his kids permission to watch Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, even though it’s almost bedtime. “Roy, that movie’s four hours long,” complains his wife, Ronnie (Teri Garr). “I said they could watch five commandments,” he answers.

Writing in The New Republic when the film first appeared, critic Stanley Kauffmann argued that Close Encounters “is not so much a film as an event in the history of faith.” It’s a movie about the power of movies, but it’s more than just an exercise in self-reflexivity. For a society awash in technological innovation, he argued, Spielberg’s brand of movie magic becomes a uniquely potent force. It excites and convinces, but, ultimately, comforts and soothes. Yes, there’s life out there, Close Encounters tell us, but not to worry: They like us. In Kauffmann’s conception, the director is much more than mere entertainer. He is a saintly figure imparting holy bliss. He’s also engaged in the ultimate act of chutzpah: He leads us to Mount Sinai only to reveal his own creation.

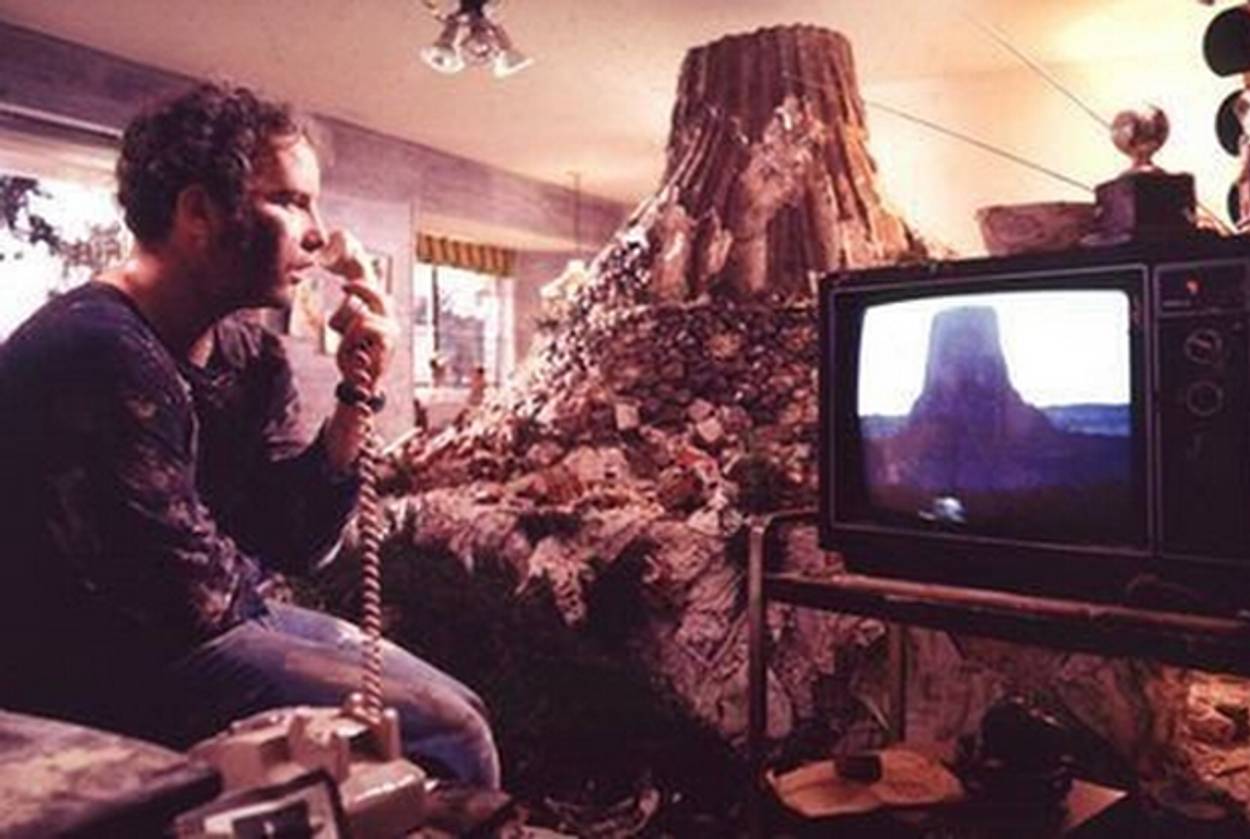

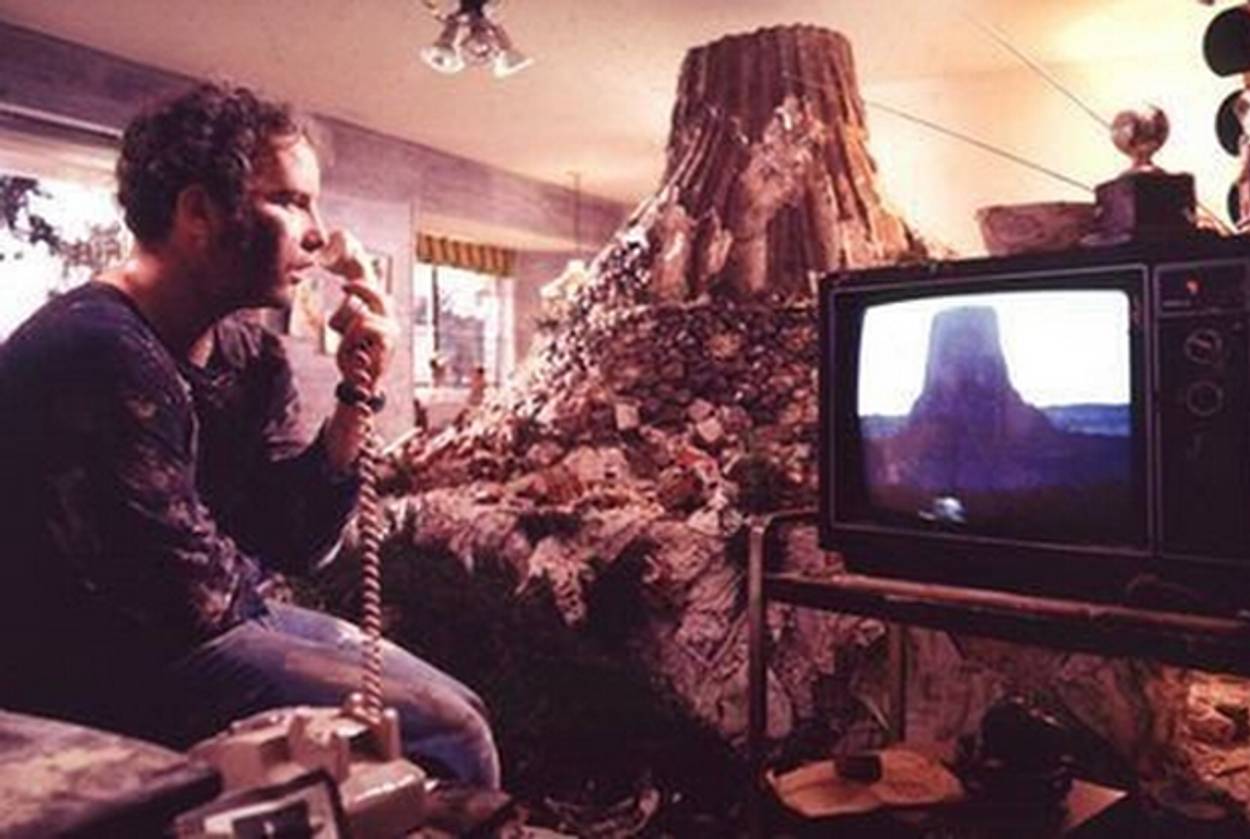

Creativity and the creative process are central motifs here. Roy Neary gets an idea and spends much of the movie trying to make it real. After his first encounter with an alien ship, he gets an image stuck in his head—an image of the mountain, Wyoming’s Devil’s Tower, where, in the film’s final act, the alien mothership will make its dazzling descent. But before Roy understands just what the image is, he fashions more and more sophisticated representations of it: first with mashed potatoes, then with clay, and, finally, with a sculpture that takes up the better part of his living room.

Roy enhances and refines and perfects his vision as a film director might. (Here’s Spielberg in 1980 with a scale model of one of his Raiders of the Lost Ark locations.) Perhaps it’s no accident that the staging area set up for the spaceship’s arrival, with its glaring lights, copious sound equipment, and bright white screens—to say nothing of the throngs of people waiting for something, anything, to happen—bears a strong resemblance to a movie set.

Wide-eyed and wildly ambitious, Close Encounters is a young man’s film. In a 2005 interview, Spielberg, who made the picture before he had children, said that now that he’s a father he wouldn’t be able to end the movie with Roy climbing onto the spaceship and leaving his family behind. The director’s view of America and American institutions has also changed. In Close Encounters, the army does nothing but lie and deceive—a state of affairs far different from the one Spielberg offers in, say, Saving Private Ryan.

In Close Encounters, Spielberg goes up the mountain in order to subvert it—and he announces his own arrival in the process. In more recent years, he’s had his sights set on a more conventional sort of Sinai. Back in the 1970s, five commandments was enough. Nowadays, he’s interested in the full 10.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind will be screened at New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage on Wednesday, July 23, at 6:30 p.m. as part of the free summer-long series Close Encounters of the Spielberg Kind, which will continue every Wednesday through August 13.

Gabriel Sanders is Tablet’s director of business development.