In Israeli Prison, a Captive Audience for Rockets

Palestinian and Israeli inmates take cover alongside guards when sirens blare

When the rocket sirens go off in this warehouse district of Ashkelon, no one stops to take a picture with their cell-phone of the Iron Dome intercepting the rockets, and everyone knows exactly where to run. To be fair though, that’s probably because the 550 inmates have all had their cell-phones confiscated and have heard on average about eight rocket sirens per day during the past few weeks, giving them more than enough chances to practice.

“On the outside they have the choice to run or not when there’s a siren. But here, they have no choice but to take cover,” said junior commissioner Avraham Miron, who runs the facility.

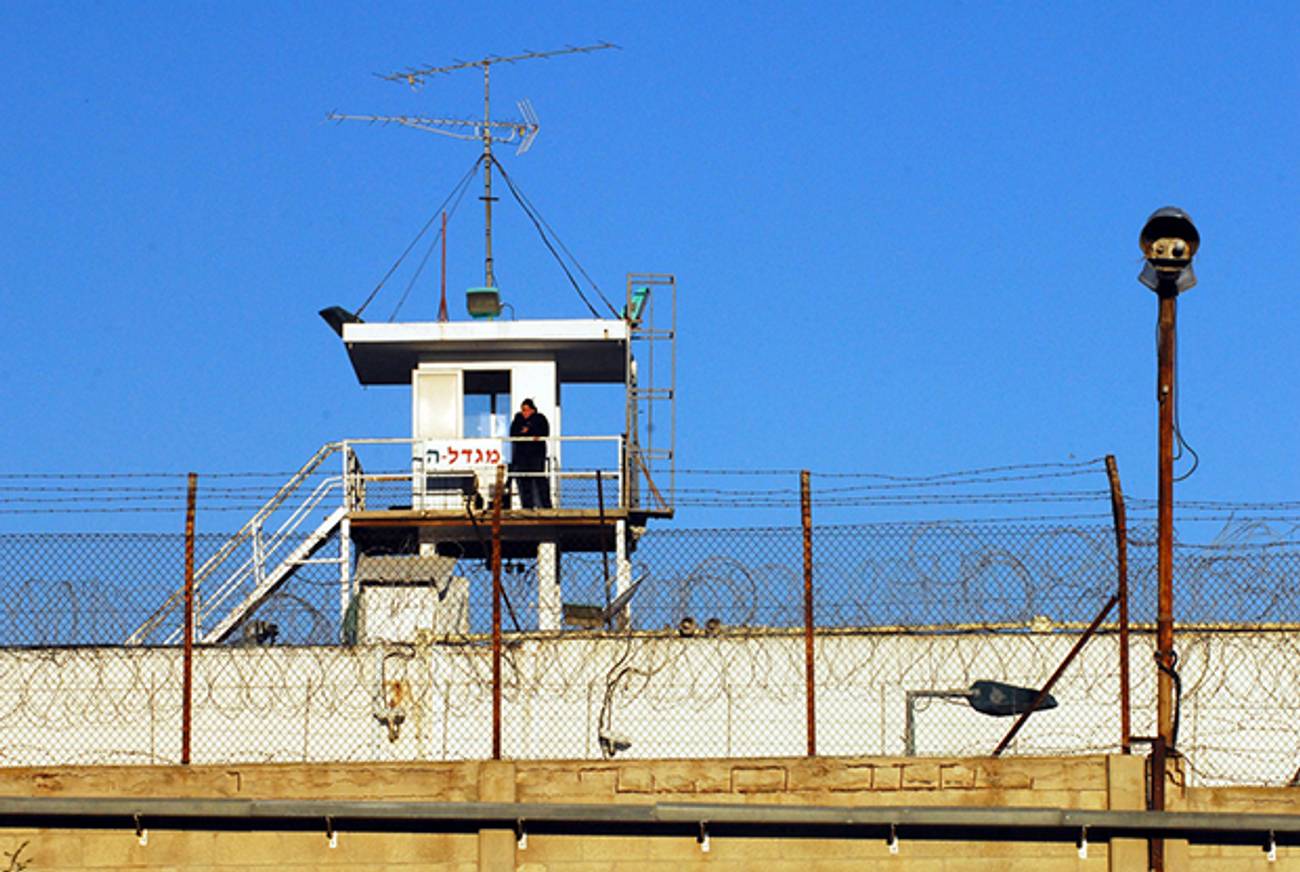

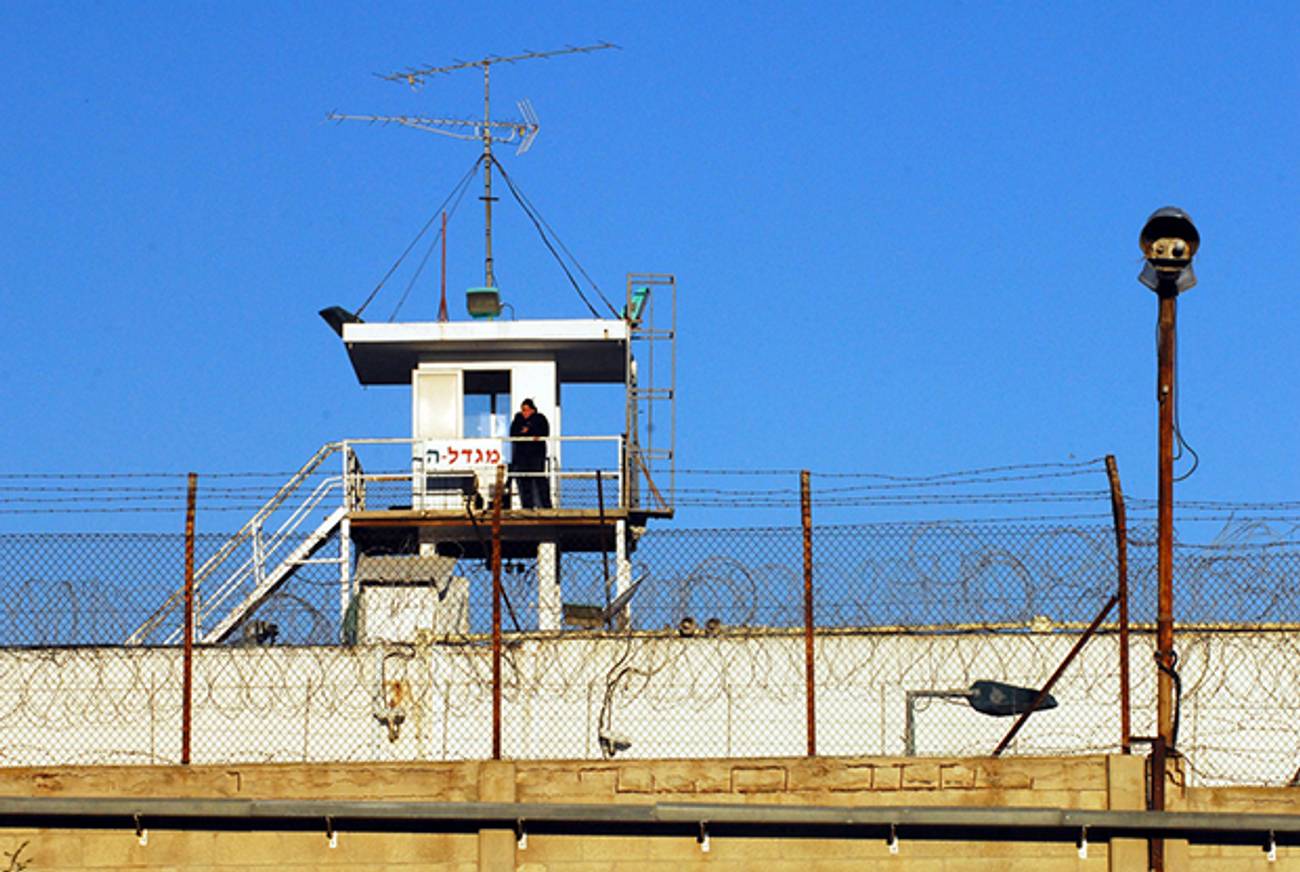

Shikma Prison is an aging facility in the north Ashkelon industrial district housing 480 Israeli inmates—most of them pre-trial—as well as 70 Palestinian security prisoners. It’s part of a city that has been hit by rocket fire as hard as anywhere else in Israel this month and where, to make matters worse, you have only 15 seconds to seek cover when the rocket siren sounds.

A little more than two weeks ago, as Operation Protective Edge was starting, Miron ordered 250 prisoners housed on the more exposed second floor of the facility to be moved to other prisons farther from Gaza, saying it was easy to maintain control of one floor of inmates during the sirens.

He said his job as warden “is to protect the lives of inmates and to keep them away from the public,” saying that his staff has repeatedly drilled themselves and inmates on what to do when the siren goes off: get in your cell and stand away from the window against the concrete walls, or if you cant, then stand against the concrete walls of the cellblock hallways. Unlike civilians on the outside, they are never far from the protective, thick concrete walls and metal doors that offer safe cover.

In a strange twist of fate, the prison reportedly has held among its security prisoners Dirar Abu-Sisi, the Gaza engineer believed to have been kidnapped by Israeli agents in Ukraine in 2011, and who the Shin Bet referred to as the leading Hamas rocket developer.

When asked if the “Rocket Godfather” of the Gaza Strip also had to take cover in the prison from the rockets he helped develop, Miron said only “there are very many things here that aren’t logical.”

Marina Smoler is a 32-year-old mother of two children ages eight and three from Ashkelon who works as an Israel Prison Service social worker at Shikma. She said that the prisoners spend much of their days glued to the TV sets in their cells watching news of the operation and the rocket barrages. A big part of her job in times like these, she explained, is talking to them about the stress and concern they’re feeling.

“Most of the prisoners here are from the south and after a siren they want to call home, so they split up the phones by who’s from where and where the rocket fell.” Marina said. She added that as an Ashkelon resident it’s a problem for her too, but that she has a job to do. This is the third major Gaza escalation since she started working at the prison six years ago, she added.

Cell block officer Keren Vazana-Aviram is a 42-year-old mother of four from a small moshav in the Hof Ashkelon council, another area that has been heavily pounded by rockets over the past two weeks. For the 66 prisoners in her cell block, the rocket fire “tends to cause them to feel guilty that they aren’t there with their families on the outside,” adding that the regret can be a good topic to bring up in their rehabilitation process.

“Yossi,” a father of two serving a 46-month sentence for bribery charges, seemed to feel that sense of guilt. He said being from the center of Israel he never had to deal with rocket sirens much before being housed at Shikma, and that not only is he learning to get used to it but so are his wife and kids, as central Israel has also been heavily targeted by rockets in recent weeks.

He said that the stress of the sirens and the conflict can serve to unite the prisoners, at least while the rockets are falling.

“I think it kind of brings the prisoners together. If I’m on the pay phone and I hear that the rocket struck in some other guy’s town, I’ll let him use the phone to call home.”

Previous: A Jewish Prisoner Discusses Repentence

Related: Spiritual Healing Behind Bars

Ben Hartman is the crime and national security reporter for the Jerusalem Post. He also hosts Reasonable Doubt, a crime show on TLV1 radio station in Tel Aviv. His Twitter feed is @Benhartman.