Nazi Guard Charged With 300,000 Counts of Accessory to Murder

Oskar Groening, 93, to face trial in Germany for role at Auschwitz

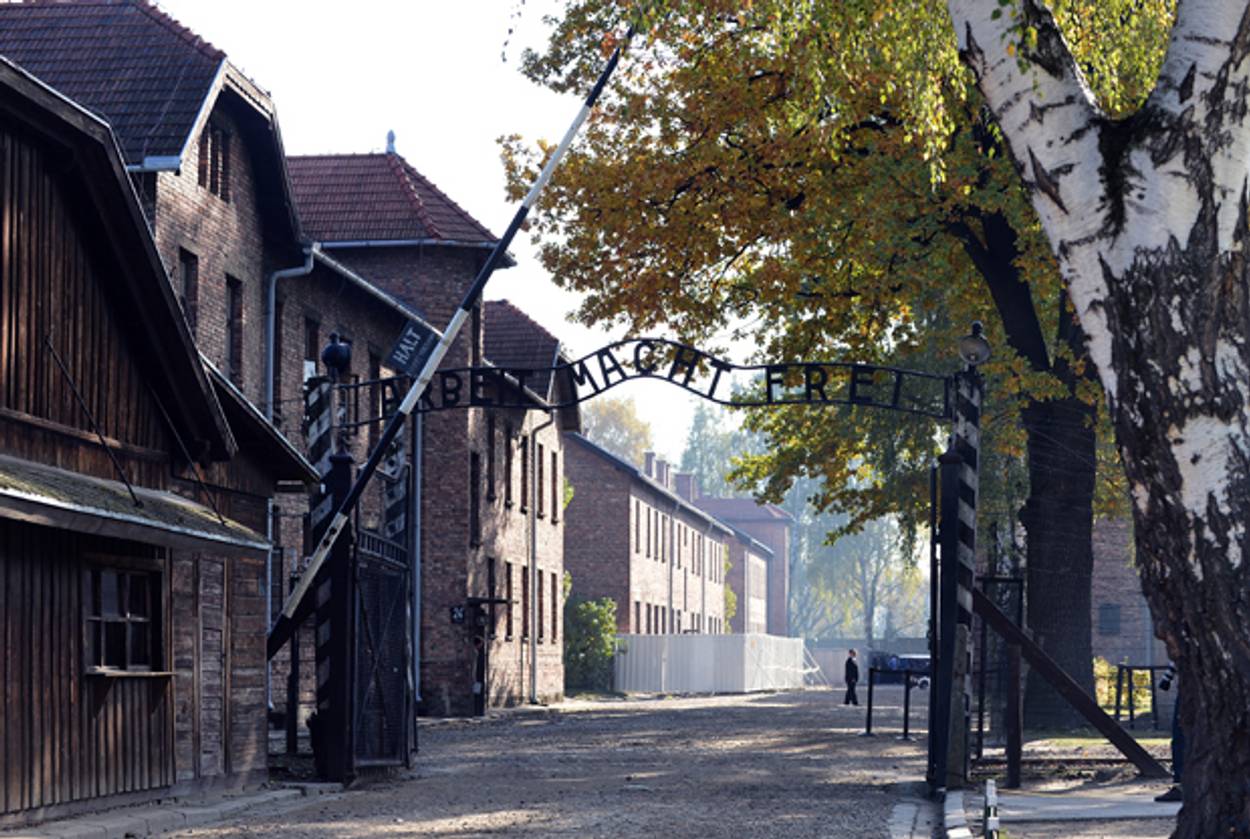

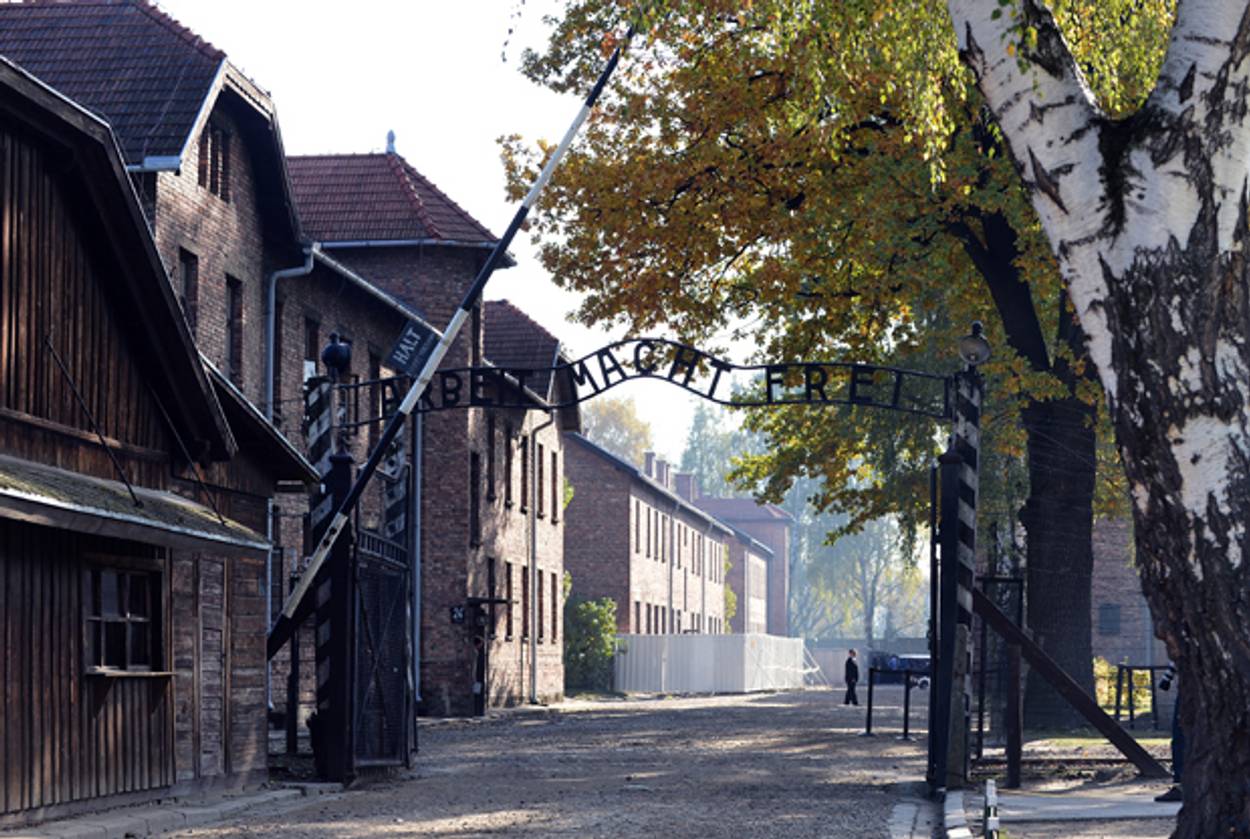

Although it’s become clear that 21st century anti-Semitism in Europe is not as unusual a phenomenon as we may have hoped, something strange, if not extraordinary happened in Germany this week: a former Nazi guard at Auschwitz was charged with accessory to 300,000 murders during his time at the concentration camp.

According to the Associated Press, the man in question, 93-year old Oskar Groening, is suspected to have helped operate the camp when almost half a million Hungarian Jews were imprisoned there. Most of them were sent to gas chambers shortly after their arrival.

But there’s something fundamentally problematic about how rare it is that a Nazi finally be charged with a crime. In fact, Groening has been under investigation for quite some time, and was even interviewed by Der Spiegel in 2005 about his various jobs at the camp. He’s been a controversial figure—comfortably living in Germany for the past few decades.

The fact is that very few high-level guards and officers ever stand trial. Often, they end up dying before their trial dates. Samuel Kunz died under indictment in 2010 at 89; The Simon Wiesenthal Center’s most wanted criminal, Laszlo Csatary, a famously vicious police commander, died at 98 after finally being detained by Hungarian authorities; Johann Breyer, the Nazi guard arrested in Philadelphia, died in July the day before his extradition hearing. Even the living ones manage to escape trial: earlier this year 94-year-old Hans Lipschis was excused from trial due to dementia. Two other criminals investigated as a part of Groening’s case have been deemed unfit for trial as well.

The question, of course, is why it takes more than half a century to bring war criminals and murderers to trial. As one can only imagine, the answers are bafflingly evasive: evidence was scarce, or authorities simply could not locate the criminals or manage to have them extradited. It’s sort of like the question of why FDR didn’t go ahead and bomb concentration camps and their feeder tracks once he knew about them: Sometimes there just isn’t a logical answer.

But it is important that an SS guard finally be charged with his crimes. Earlier today, German Chancellor Angela Merkel announced that she wanted “Jews to feel safe in Germany.” These small victories are necessary.

Still, at the same time there is such a thing—to use an awful proverb—as ‘too little too late.’

Groening, after all, has outlived most of the Jews who managed to escape death at Auschwitz. More importantly, can someone a week away from total organ failure really be held responsible for his role in something that happened 70 years ago? One cannot help but wonder whether the intention is to punish men like Groening before they die, or to plausibly deflect any suggestion that nothing was ever done about these men at all. And although the defense has said Groening is in good health, if recent history has taught us anything, he may likely die before his sentence—or even his trial—begins.

Previous: Suspected Nazi Dies Day Before Judge Orders Extradition

Germany Arrests Suspected Auschwitz Guards

Alexander Aciman is a writer living in New York. His work has appeared in, among other publications, The New York Times, Vox, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Republic.