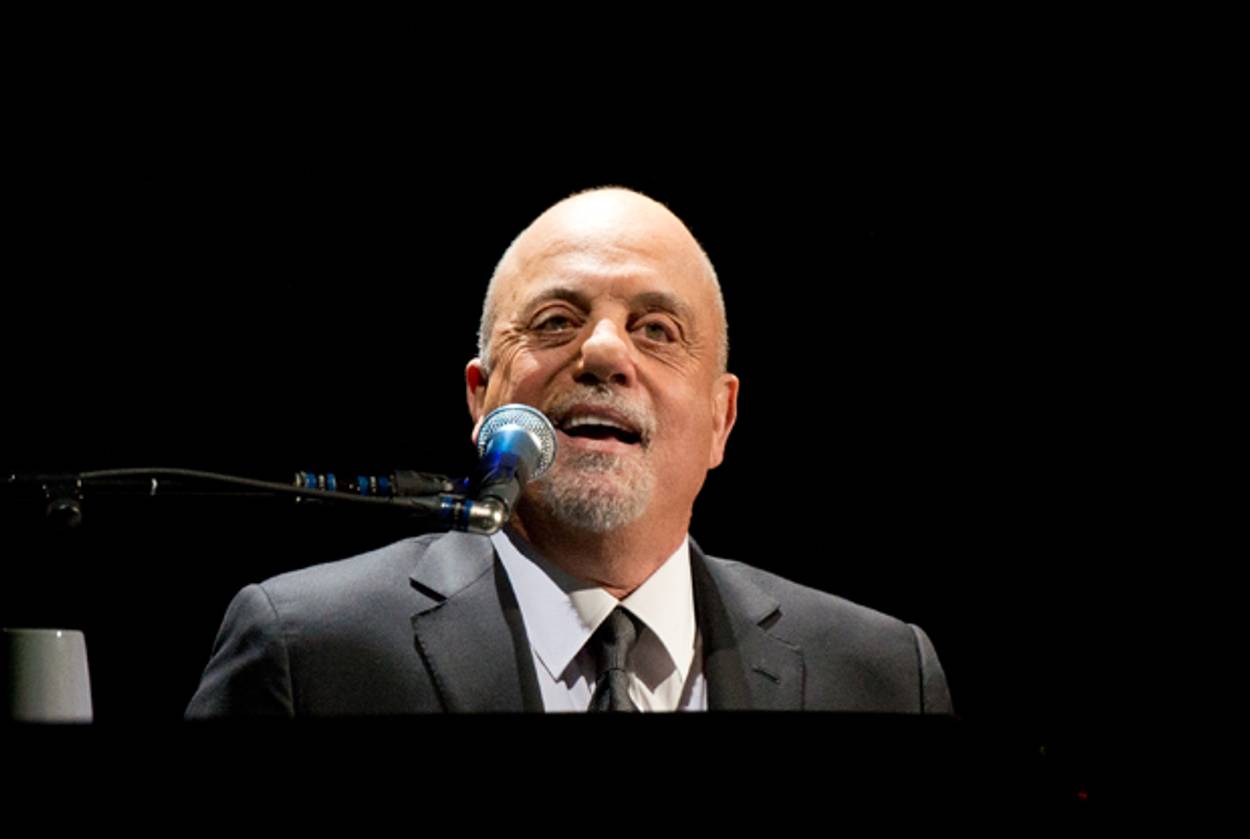

Billy Joel Honored With George Gershwin Prize

Though today’s music industry hardly resembles the Tin Pan Alley era

On Tuesday, Billy Joel will receive the Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song. At the first blush, Joel and George Gershwin, for whom the prize was named, would seem to have a lot in common.

Gershwin: Born in 1898 to Jewish immigrant parents in Brooklyn. Seriously studied piano as a boy and made his way in the music industry (as a song plugger and rehearsal pianist) through his mastery of the instrument. Broke through as a songwriter at a young age, eventually writing such standards as “Summertime,” “They Can’t Take That Away from Me,” and “Love Is Here to Stay.” In his later years, branched out to classical compositions.

Joel: Born in 1949 to Jewish immigrant parents in the Bronx. Seriously studied piano as a boy, and made his way in the music industry (as a session pianist on such records as “Leader of the Pack”) through his mastery of the instrument. Broke through as a songwriter at a young age, eventually writing such standards as “Piano Man,” “Just the Way You Are,” and “New York State of Mind.” In his later years, branched out to classical compositions.

But on closer examination, the comparison breaks down. Gershwin came of age in the very heart of the Tin Pan Alley era, when there was a piano in virtually every American middle-class home and sheet music sales were paramount. As a teenage song-plugger for the Remick publishing company, A young George Gershwin traveled all over New York City in the hope that his rendition of such tunes as “Honolulu Ukulele Baby” would inspire punters to hand over a dime to have the chords and lyrics at their fingertips. In 1918, another publisher, the prescient Max Dreyfus, sensed Gershwin’s potential and hired him as a staff composer at a salary of $35 a week. For every published song, Dreyfus would give him a $50 advance, against royalty payments of three cents a copy. Gershwin’s brother, Ira, summed the deal up in his diary: “Some snap.”

Subsequently, George and Ira, a lyricist, teamed up to write Broadway shows and film scores. The Hollywood fees were generous—George was paid a flat $70,000 in 1930 to write the songs for a movie called Delicious—and they got significant box-office shares of their shows. By the time Gershwin died of a brain tumor in 1937, songwriters were as rich as heavyweight champions and almost as popular as movie stars—largely thanks to the creations of his prodigiously talented, almost unanimously Jewish cohort, including Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, Richard Rodgers, Cole Porter (the outlying Gentile), and Harold Arlen.

The glory didn’t last, and by the early 1960s the great tradition was on its last legs. The Beatles and their progeny killed it multiple times over, perhaps most significantly by destroying the traditional division of labor between songwriters and performers. Coming up in the late 1960s, Billy Joel always aspired to both roles. Unluckily, he aligned himself not with a latter-day Max Dreyfus but a manager named Artie Ripp, who convinced him to sign a disastrous deal that, as a recent New Yorker profile of Joel put it, “basically gave Ripp the rights to everything, forevermore.”

Joel eventually got his publishing rights back, but even so, songwriting wasn’t—and isn’t—the kind of gig it had been in Gershwin’s day. Sheet music royalties are now a trickle in the revenue stream, if that. Somewhat more robust are broadcast payments, though they’re nowhere near where they probably should be. As for record sales, songwriters split with their publishers a fee of about nine cents on the dollar of record sales (and split that amount with co-writers, if any). That can add up if a record sells. But thanks to legal and illegal downloads and, more recently, streaming, records basically don’t sell anymore. Streaming services—Pandora, Spotify, and YouTube—pay infinitesimal royalties to songwriters, some of whom have taken to posting online screen shots of their royalty statements.

Billy Joel doesn’t need to sweat small stuff like that. He’s written and recorded virtually nothing since the early 1990s, which hasn’t hurt his bottom line. He makes his money touring: According to Pollstar, as of July, Joel’s 2014 concerts had grossed $50.3 million, second only to George Strait.

Clearly, Billy Joel is an exceptional case, and an exceptional talent. Arriving on the scene not long after Carole King, Burt Bacharach, and Paul Simon (all Gershwin Prize winners), plus Marvin Hamlisch and Bob Dylan, and the team of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, he is also probably the last in a line of great Jewish songwriters that had started way back with Berlin, Kern, and Gershwin.

What hope would, say, a child of Vietnamese immigrants, born in Queens in 2000, have of winning the Gershwin Prize decades from now? Clearly, if she wants to write pop songs for the ages, she has to be willing to buck the tide. But she and other digital-age songwriters may one day benefit from a recent development: longtime music manager Irving Azoff has signed Smokey Robinson, Pharell Williams, and the estates of Ira Gershwin and John Lennon to a new venture called Global Music Rights, which aims to secure better streaming deals for both writers and performers.

It’s obviously impossible to tell whether these developments or others will end up restoring music industry conditions to a place where great popular songwriting will once again thrive. But I’ve got one rock-solid piece of advice for that 14-year-old Queens kid: don’t stop with the piano lessons.

Ben Yagoda is a professor of journalism at the University of Delaware and the author of the forthcoming The B-Side: The Death of Tin Pan Alley and the Rebirth of the Great American Song.

Previous: Billy Joel to Begin Monthly Residency at MSG

Related: Block Party

Rags and Riches

Ben Yagoda is a professor of journalism at the University of Delaware and the author of the forthcoming The B-Side: The Death of Tin Pan Alley and the Rebirth of the Great American Song.