Study Claims Yiddish Originated in Turkey

The messy, ideological battle over the beginnings of the Yiddish language continues in the academe

Editor’s note: A version of this article, published on Tuesday, did not properly describe the decades-long battle over the mysterious origins of the Yiddish language—a “weakening” academic battleground marked by petty, ideological fights—which we covered in a two-part series in 2014.

Researchers from England, Israel, and the United States are arguing that the Yiddish language may have originated in Turkey, rather than anywhere near Germany, and may be more Slavic than German. The study, published in the journal Genome Biology and Evolution last month, uses a so-called ancestral DNA tracking GPS (“Geographic Population Structure”) tool to pinpoint where the first Yiddish speakers may have lived, over 1,000 years ago.

One of the paper’s co-authors, Paul Wexler, a linguistics professor at Tel Aviv University, was featured in Tablet’s two-part series on the origins of Yiddish, published in 2014.

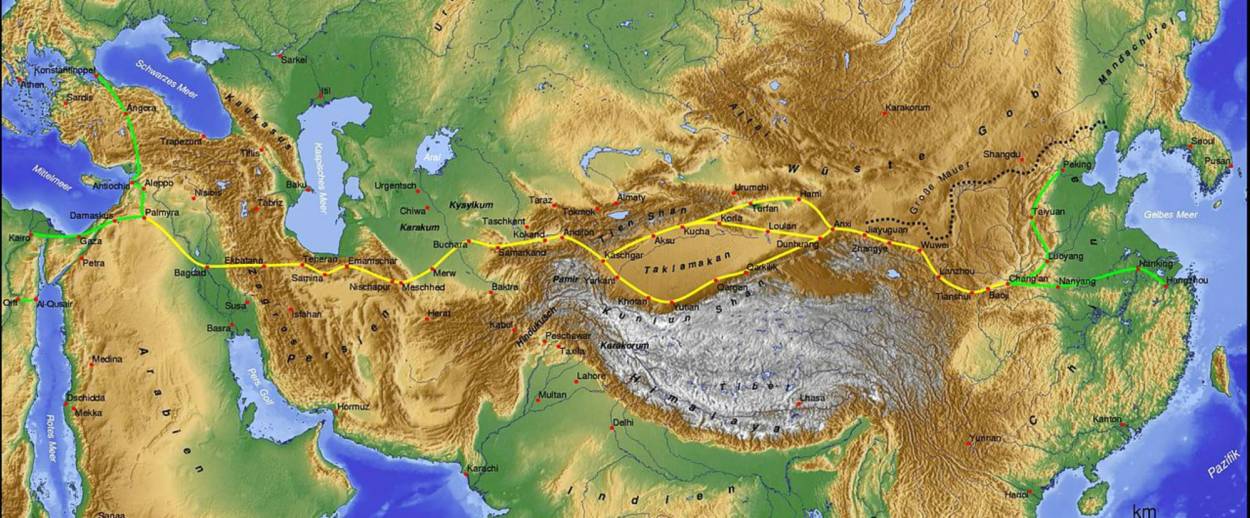

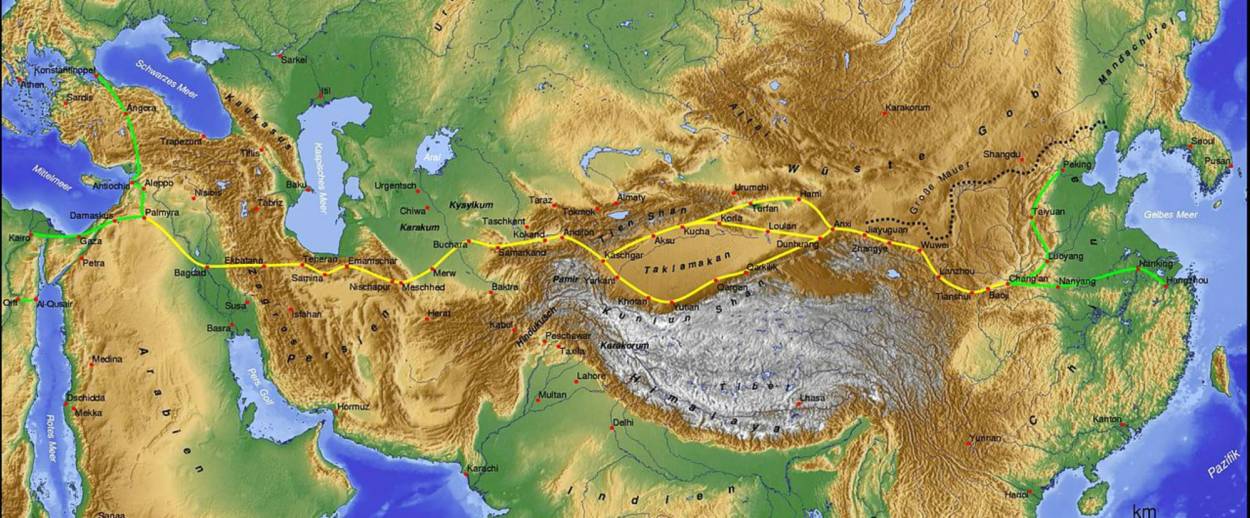

In the first article in that series, written by the late Cherie Woodworth, entitled “Where Did Yiddish Come From?”, Wexler is described as having “marshal[led] his arguments for two decades to make the radical, implausible, impossible argument that Yiddish did not come from Germany but from the Slavic lands, and the East European Jews came not from the Rhineland but from Persia via the Caucasus and the Khazar steppe.”

Woodworth examines examines and compares Max Weinreich’s History of the Yiddish Language, and his “Rhineland theory,” with Wexler’s “Slavic theory,” which challenges Weinrich by averring that “Yiddish has Slavic grammar, syntax, morphemes, phonemes, and lexicon, with a smaller input from Turkic.”

This claim, that Yiddish originated in Turkey, is the latest in a string of theories about the language’s beginnings, which reside in an academic field doomed by petty fighting and misguided ideological debates, writes Tablet contributor Batya Ungar-Sargon in “The Mystery of the Origins of Yiddish Will Never Be Solved.”

In the past two decades, the debate has shifted. One the one side of the debate are Weinreich’s inheritors, who believe that Yiddish originated in Western Germany in the Rhineland and spread east. On the other side of the debate are those who think that eastern Yiddish, with its heavy Slavic influence and Bohemian vowel structure, is different enough from western Yiddish that it must have arisen independently. But because this is Yiddish linguistics, this debate does not exist so much as rage—intellectually, ideologically, and personally.

To grasp a deeper understanding of the academic and identity politics at play with Wexler’s new co-authored paper, consider Ungar-Sargon’s narrative detailing the main conflict residing in the Yiddish academe, which, in and of itself, “represents the conflict at the core of Jewish identity,” Jonathan Brent, the director of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, told her.

The main debate among Yiddish linguists is about the origin of the language and coalesces around a single, unexpectedly loaded question: Is Yiddish an essentially Jewish language, one that contained a Semitic component from the start, whose particular combination of Jewish and German elements precisely reflects the dance of contact and seclusion performed by Jews in their European Diaspora? Or is it just another dialect of German?

The conflict, writes Ungar-Sargon, “has ballooned in importance, becoming a place where both the past and the future of the Jewish people is battled over, one phoneme at a time, through a combination of academic and extra-academic means. Threats of legal action are par for the course. So are character assassinations, pseudonymous academic hits, accusations of lunacy, and denials of the existence of the Jewish people.”

Wexler’s Yiddish origination theories are what Ungar-Sargon calls “fringe,” relying on a position that “Yiddish is neither German not Jewish but a Slavic language with German and Hebrew words slotted into Slavic grammar in a process called ‘reflexification.’ “

The word Ashkenaz itself, he argues, only acquired its present referent—Jews of Germany—after the 11th century. It comes from a biblical word that signified the Scythians, in other words, the Iranians; for Wexler, this provides a crucial clue as to where the Jews came from and who they were prior to this date. Indeed, Wexler does not believe that the Jews were forced out of Palestine in the Roman period, but rather, that the Ashkenazi Jews are descendants of Iranian, Turkic, and Slavic converts to Judaism.

And here’s where things get thorny. “I deny the existence of the Jewish people,” Wexler told me on the phone. “Ninety-five percent of the Jews are of Iranian origin.” But Wexler insists that he did not set out to prove such an extra-linguistic thesis. “This was not my goal. It turns out to be the logical conclusion of my linguistic theories.”

In light of Wexler’s recent paper, titled “Localizing Ashkenazic Jews to primeval villages in the ancient Iranian lands of Ashkenaz,” (co-authors are Ranajit Das and Eran Elhaik of the University of Sheffield, and Mehdi Pirooznia of Johns Hopkins University), read Ungar-Sargon’s article for a window into Yiddish academic history and “culture, one that puts the cart of ideological conclusion before the scientific horse.”

Rose Kaplan is an intern at Tablet.