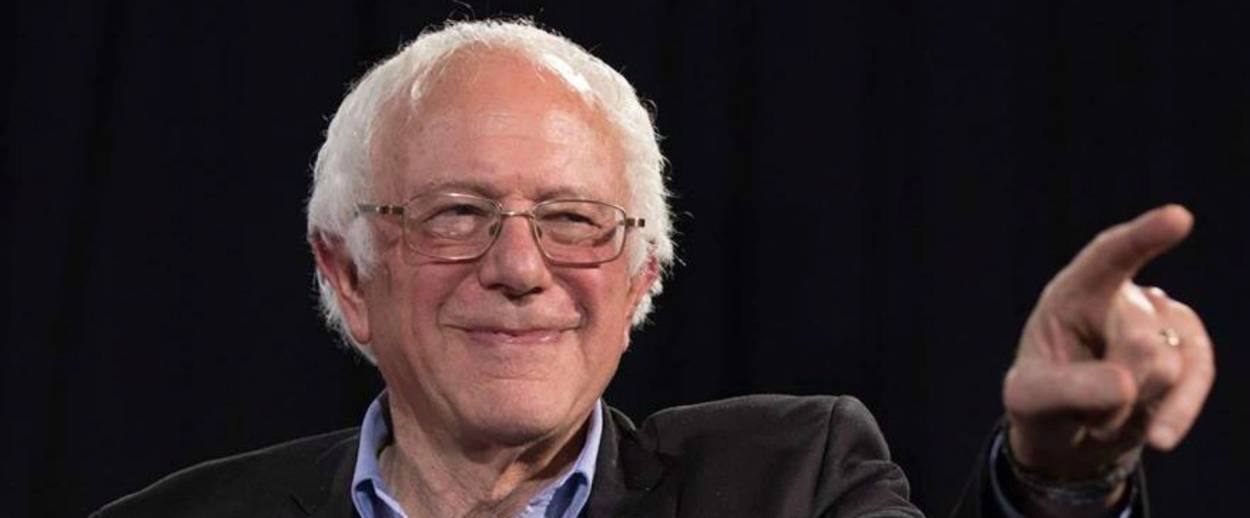

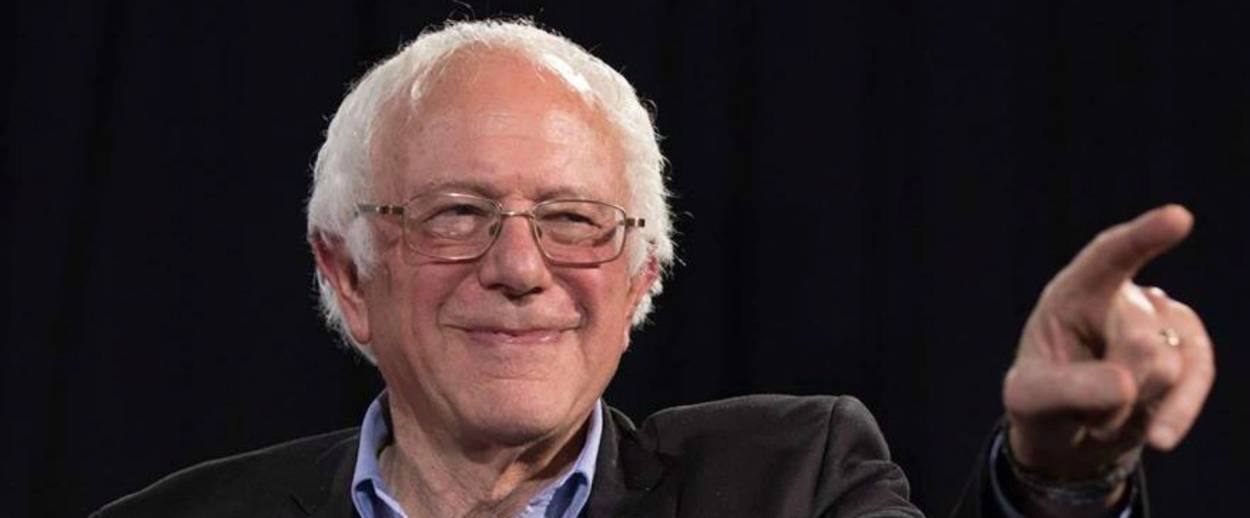

Bernie Takes His ‘Revolution’ on Tour

But this time he’s touting his book, and not a presidential candidacy

On Monday, as I headed to a Bernie Sanders event at the Philadelphia Free Library on a crisp, cloudless night, I encountered a short man with smudged glasses handing out flyers outside the venue. There to drum up tickets for a documentary on the Men’s Rights Movement, a minor community of American males besieged by a mainstream social order deaf to the quiet ways in which they are oppressed, he sought out kindred spirits willing to spend $12 on an evening in the suburbs learning why men need more compassion. Inside, a round-faced woman in her early 20s sat in the front row. She had “Bernie” buttons on the lapels of her grey pea coat and a copy of Our Revolution, the new memoir/ manifesto Bernie was in town to promote, open on her lap.

“A year ago all the groups wouldn’t listen to me,” she said of the young Democrat gatherings in her hometown outside the city. “So of course now I have all the info I need to show them what we should have been taking about all along, before it was too late.”

She, like much of the sold-out crowd, still weathered the effects of the election and the mounting evidence that they live in a nation of strangers now governed by an unfamiliar force of dubious moral fiber.

The gloom lifted when Sanders appeared on the tiny stage to a standing ovation that could just as well have been for someone who’d actually won something. Sanders said that Trump took the election by tapping into a pain and anxiety not fully captured by the mainstream press. Trump, he said, promised to assuage their desperation by taking on the establishment media, politicians, and financiers who have ignored the reality of living in America, and ran a campaign that in certain ways echoed the proposals to restructure the faulty social order outlined in his book. Sanders, perhaps sensing a cognitive dissonance arising in the minds of his supporters who were just told that a simpler, coarser, gaudier version of their defeated candidate’s platform was used to place the White House keys into the butter-colored hands of a Snapchat P.T. Barnum, swiftly pivoted to an anecdote. “You’re a single mom, in Philadelphia, making thirty, forty thousand dollars a year,” he said. “You have a baby. You need childcare in order to get to work. You know how much childcare costs?”

Someone told him $15,000.

“What do you do if you’re making $30,000, $40,000 a year and paying $15,000 in childcare?” he asked. Then, curiously, Sanders abandoned the vignette. “I can tell you in Washington, D.C. I had a young woman working for me and she was paying $32,000 for childcare.” The crowd dutifully gasped at the sticker price; Sanders quickly adds that costs are higher in Washington.

Sanders’s then segued into a torrent of facts about healthcare costs that force seniors to split their heart pills into two pieces because they cannot afford the prescription. The mothers, both imagined and real, had become distant memories, overwhelmed by the facts and stats and avalanche of so many problems for so many people requiring so many solutions.

Journalist and host of Democracy Now Amy Goodman later joined Sanders on stage. She asked him, considering his influence and power, “What can you do right now?”

Goodman, who has been covering the Native American protests at the Standing Rock Reservation, against the construction of a $3.2 billion oil pipeline that threatens the drinking water there, spoke about the violence unfolding in North Dakota. Amy’s cameras had captured security guards and, as she told the audience, their attack dogs with “noses and mouths dripping blood from biting the Native Americans.”

After some throat clearing Bernie answered the question about the extent of his functional power by deferring to Obama. “We’ve written to the president, and we will continue to put pressure on the president to do everything he can to protect Native Americans in the area.”

Goodman did not press Sanders on the emerging subtext: Obama, like Sanders, had galvanized a large swath of disillusioned American left, winning two presidential elections, might be more capable in whatever role he happens to take after leading the free world, in absorbing the nation’s disparate granular realities and myriad pains and needs into a sweeping narrative that few individuals have historically been able to leverage into positions of great power and influence. Instead, Amy asked Sanders if he regretted not chastising Hillary’s use of a private email server during the debates, deferring the potential score of political points to admonish the media to “forget the damn emails.” He had no regrets, he said, because in 10 years no one will remember the emails, but they will remember no one having healthcare, rising poverty, climate change, crumbling infrastructure, expensive education, the collapse of the middle class.

The crowd slowly drained out of the library, new books in hand. And when they get home, they’ll make their way through the book having just heard the highlights from the author himself, and get themselves ready to fight the revolution he so carefully put down on paper.

Sean Patrick Cooper is a journalist who has contributed narrative features and essays to The New Republic, n+1, Bloomberg Businessweek, and elsewhere. His first book, The Shooter at Midnight: Murder, Corruption, and a Farming Town Divided will be published in April 2024 by Penguin.