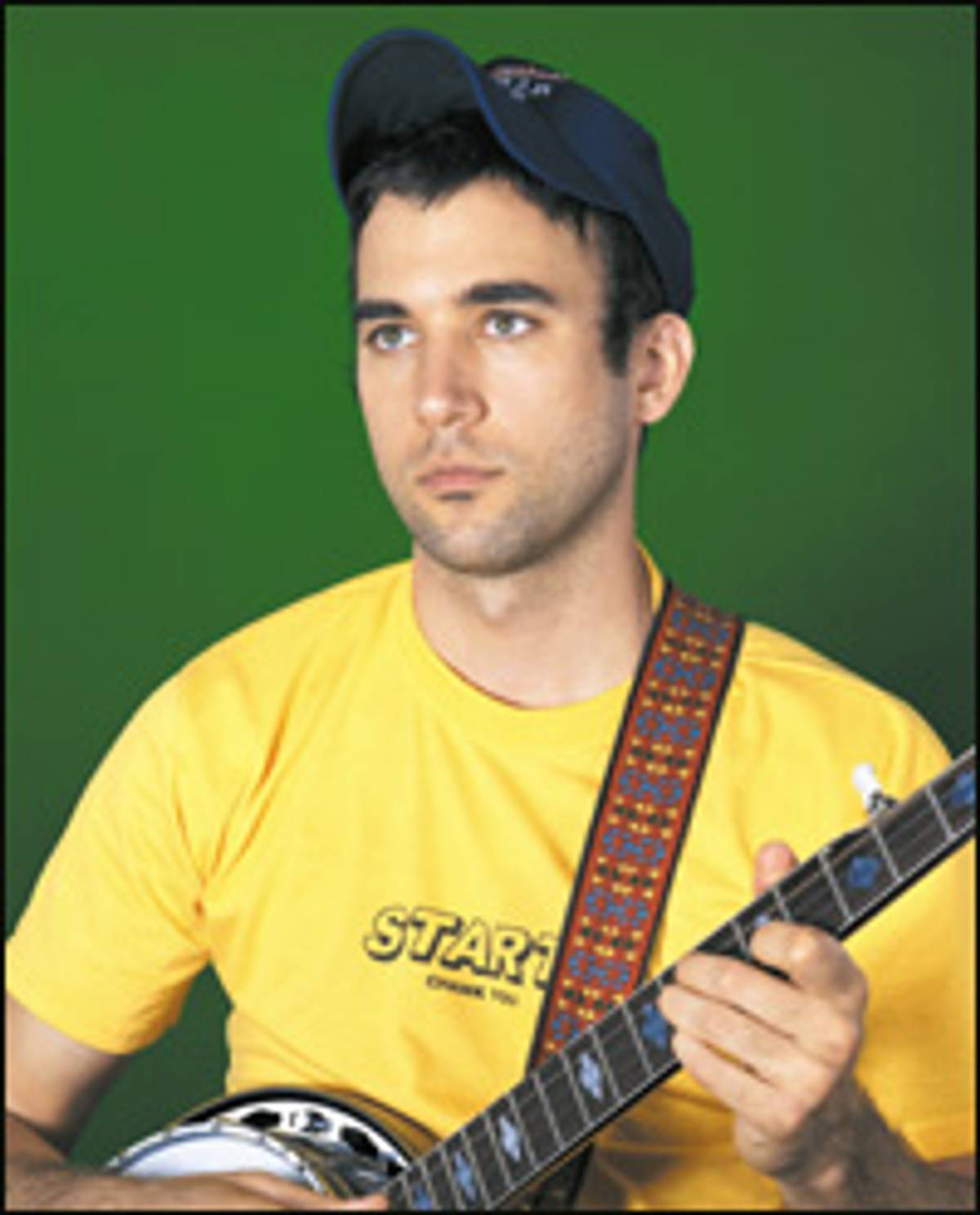

I fell fast for Sufjan Stevens. It wasn’t just his delicate, half-wounded voice, or his unexpected arrangements, sincere and silly at once, heavy on glockenspiel and vibraphone. Listening to his Michigan album—the first of a projected 50, cataloguing every state—what I loved most was his lyrical dexterity, desperate one verse, enthusiastic the next, weaving elusive ballads and ironic, encyclopedic pageants set among local lakes and cities. But the song that haunted me most, “He Woke Me Up Again,” wasn’t on Michigan—it was on Seven Swans, a follow-up album that left the 50 States Project for Christian confession. I heard it first on a recorded radio session, replayed it constantly, and, sometimes, embarrassing to admit, sang along to the chorus, “Halle Halle Hallelujah, Holy Holy is the sound.” The supposedly secular Jew in me was baffled—not only did I enjoy Stevens’ religious exclamations, I hardly minded the God he was praying to was not my own.

What then would Stevens sound like singing about Bellow, a writer credited with, among other things, the very name of this website? And would he get me to sing along?

On first listen, “Saul Bellow” is lovely but mildly mystifying, in the way many of Stevens’ songs are—they have an internal logic, their narratives only opening after multiple exposures—its chorus echoing “Getting solid walls/ With the know-it-alls/ Get in trouble with Saul Bellow.” It turned out “Saul Bellow” is not so much a song about the novelist as about Stevens’ trouble singing about him.

“I had been reading a lot of his stuff to get a sense of the background and the character of Chicago,” Stevens told me one afternoon over the phone, “but I found him to be a difficult subject for a song.” That was back when Stevens began Illinois ; unlike Michigan, which drew on Stevens’ own upbringing in the Great Lakes State, Illinois relied heavily on research, whether memories borrowed from friends, stories of a UFO sighting near Highland, or reports on John Wayne Gacy. First on Stevens’ reading list was The Adventures of Augie March, but Stevens said, “Every time I tried to sing about Saul Bellow, I was up against the solid wall of his intelligence, and I had a hard time scaling that. He’s so academic, so sort of pseudo intellectual and his writing is about big ideas and big concepts.” “Saul Bellow” may be named for the author, but in Stevens’ mind, it’s really about “the difficulty in dealing with big ideas, big constructs, in music. And if the constructs get out of hand, instead of sounding personal, and sounding real, you start sounding like you know everything.”

Nodding along, I felt quietly pleased to hear Stevens’ mild takedown of Bellow, sensing a new-found kinship in our shared frustration. Yet Stevens also heard echoes of his methodology in the opening lines of Augie March—”make the record in my own way.” It was enough to get me to give the novelist another chance.

I started where Stevens did, with “Chicago, that somber city,” fully prepared to agree with Stevens’ assessment that, “even though he’s writing about his experience, about a particular subculture of the alleys of Chicago, he writes about it from a philosophical vantage point that condescends to the characters.” I got to the second sentence “But a man’s character is his fate, says Heraclitus,” and I nearly threw the book down—Heraclitus! What better proof of condescension—and then didn’t. I kept reading, past the often-quoted opening to Bellow’s fine descriptions of Grandma Lausch, “not a relation at all,” but an Odessa widow who runs the March household, and Winnie, the “pursy old overfed dog” at her side. If I dug deep, I suppose it recalled stories I’ve heard about my great-grandmother, who lived in an apartment above my mother’s in a neighborhood nowhere near as poor, and spoke in thick Yiddish accent to the family’s plump cockerspaniel, “Freckles, are you hungry?” But in other ways, Grandma Lausch is more vivid, more alive than my great-grandmother ever will be to me—a day after reading the opening chapter, I found myself recounting stories about her as I might describe a run-in on the subway. What I loved about Augie March was what I loved about Sufjan Stevens—their distinct sense of character and place, and the ways the two intertwine.

The song “Saul Bellow” winds up sounding far more bleak than Augie March ever reads, its opening line, “What’s the worth of/ All the work of my hands?” drawing out a working class anguish that can be heard in Bellow’s prose, hiding beneath the narrator’s bravado. It’s only a fragment, and not the best song on the album, but you’ll still catch me singing along. Saul Bellow and I have had our troubles, too—who knew Sufjan Stevens would bring us back together?