A Door Opens

The author of ‘Stern’ remembers his heady first days on the literary scene

There is a moment—much longed for—in the life of the occasional writer when a door seems to swing open. Darkness becomes sunlight. The writer feels anointed, ready to step forward and to claim a reward for what often felt like years of pointless effort.

A door opened for me—just a crack—in the early 1960s, when my novel Stern was accepted for publication by Simon & Schuster. Or at least it seemed to have been accepted. There was something about it having to be made official, a procedure that lasted for several excruciating months, very much like the Sitzkrieg, the 1939 German invasion of Poland, when Germany, France, and England seemed to be at war but did little but glare at each other.

Finally, the official word did come through, and I was invited to come say hello to the staff at Simon & Schuster. First out of the gate to congratulate me was Mr. Simon, who was well along in years.

Nice to meet you, Friedman, he said. I’ve so admired your Dust Bowl novels.

Forgive me, sir, I said, but you may have me confused with another of your authors.

I don’t think so, he said, suspiciously. But thanks all the same for stopping by.

A group of young editors then gathered round and told me how much they admired my jacket.

Thank you, I said. My mother bought it for me at Saks. She was heartbroken that I hadn’t become a theatrical press agent. She’d been told that they all have big homes in Rockaway. But she wanted me to be properly dressed all the same.

After realizing they had been referring to my book jacket, I was treated to a lunch of carrots, celery, and radishes by my editor, Robert Gottlieb, who was ahead of his time on crudités. After we’d nibbled at our food, Gottlieb made typing signs in the air—a suggestion that I return home immediately and begin the next book. I took his advice—to an extent.

Soon afterward, Stern was published. The hero, such as he is, moves his family from the city to a distant suburb and becomes obsessed by a faceless man down the street who has told his child no playing here for kikes, then shoved Stern’s wife to the ground and may or may not have seen her (without panties). Stern’s manhood is threatened, his life thrown into chaos. Eventually, he makes some (publisher-ordered) small repair to his damaged psyche. The book was publicized as a first novel, though it was not the first I had attempted. It was preceded by a shapeless behemoth of an entity that I spent several years trying to shove uphill, as if it were an old Packard. A key character in the work—and it was work—was an early Martha Stewart type named Grace Dowdy. Her job was to tour America’s Air Force bases to buoy up the spirits of service wives who felt they were insufficient as hostesses. Her motivational message became the book’s title: You Are Your Own Hors d’oeuvres.

Why I felt I needed to write this book remains a mystery to me. Why I felt it would catch the attention of publishers is another.

Before Stern, I had published several short stories, the first in The New Yorker. This was occasion, in the early 1950s, to be carried heroically aloft on the shoulders of Bronx stickball players. During this period, word would spread, as if in the French underground, that a new J.D. Salinger story was in the works. Also considered an event was any new short story by Roald Dahl, before he transformed himself into a children’s book author and anti-Semite. (This type of transformation led to an unanswerable question for me: When Céline, as another example, is revealed to have written anti-Semitic tracts for the Gestapo, does one go back and dis-enjoy his novels?)

I received one of The New Yorker‘s trademark All of us here are delighted letters of acceptance.

All of us here in the Bronx, I replied, are delighted that all of you there are buying the story.

Someone at the magazine called to assure me that I would receive top dollar for my contribution. Actually, any dollar at all would have been more than welcome. I was still recovering from the fact that someone was willing to pay me to tell a story. To this day, I still treat literary money with reverence, to be spent with great care and consideration. I can practically hear organ music in the background as I part with each dollar, whereas film and television money exists to be thrown around frivolously.

I was invited to visit the magazine’s offices and to meet Hollis Alpert, the editor who had fished my story out of the unsolicited pile. He advised me not to get married and referred to J. D. Salinger as Jerry, which impressed me tremendously. (“Just over at that desk is where Jerry did his revisions on ‘Uncle Wiggly.’”) He said that if I was interested in a job as a writer for the magazine’s Talk of the Town section, he would put in a good word for me. I thanked Alpert for his kindness, but I had already signed on as an assistant editor at the Magazine Management Company, which published, among a myriad of other titles, Male, Men, Man’s World, and True Action, and thought it would be shabby of me to back out.

I did not see him again until many years later, on Main Street in Sag Harbor.

I discovered you, said the ageless Alpert, who after leaving The New Yorker, became film critic for The Saturday Review and wrote biographies of film stars. Discover me back.

Stern sold 6,000 copies, although, as Gottlieb pointed out, they were the right copies. With an exception here and there, this has been my pattern. I often wonder what it would be like to sell a few hundred thousand of the wrong copies.

The book created ripples here and there. The New York Times critic Anatole Broyard invited me to dinner at his home in the Village. Another guest was Ralph Ellison, who waggishly referred to me throughout the evening as Mr. Stern. Broyard invited me into his study to see his magnificent and immaculately arranged collection of books and to test the solid construction of his desk.

Bring your full weight down on it, he said.

I did so and agreed that it was sturdy. He pointed to an in basket which was designed to hold first draft pages and an out basket for work that was further along. I had no doubt that he loved books, but I felt it would be difficult to write them in this fastidious setting.

Among my insecurities was a fear that my employer would recognize himself as a minor character in the novel. Stern, who writes the editorial material for product labels, is terrified of his boss, Bellavista, described in the book as a wealthy Brazilian man with giant feet and wood-chopping teeth. My actual boss was an innocuous-looking man, easily lost in a crowd. Still, I worried that he would fire me on the spot. As with most fears of this nature, mine were in vain. His reaction to the book was to put me in for an immediate raise and to warn me that I would be making a mistake if I left the company.

I was less concerned about the reaction of my mother and father. There is a hallucinated version of my parents in the novel. My mother was a flamboyant woman, writ much larger on the page: In restaurants, she would grab celebrities and hold them by the sleeve, hollering across to the embarrassed young Stern: ‘I’ve got Milton Berle‘ or ‘I just grabbed Bob Eberle.’ My father was gentle, detached, described in the book as a small, round-shouldered man who spent a great deal of time after meals scooping up bread crumbs….

While not commenting directly on the book itself, my mother had high praise for the publisher.

They’re smart people. They didn’t get where they are by accident. They must have seen something.

I watched my father read a few pages, then look over at me and shake his head in wonderment, perhaps marveling not so much over the book, but at having produced a son who was so much taller than he was.

An idea that had taken hold at the time—or at least it had taken hold of me—was that if you aspired to be a writer and hadn’t published a book by the time you were 30, the game was over. You might as well switch professions. The literary heroes of the time—Capote, Fitzgerald, Hemingway—may have ended their lives poorly, but all got off to an early start. I missed the target by two years. Still, being a published novelist, even at the advanced age of 32, must have added some extra bounce to my step. My father noticed a change in the way I entered restaurants. My social life fanned out a bit. Mademoiselle magazine, which had much literary content at the time, came up with the idea of a photo layout in which first novelists and other assorted writers were paired up with Swedish models. My team included Norman Podhoretz, George Plimpton, and Jack Richardson, who wore a cape. Plimpton, who came across as a highly agreeable person, invited me to a little get-together the following week at his place. Taking him up on the offer, I arrived a bit early and called up to him in what I assumed was his bedroom. Can I wash some glasses for you, George? He said no, no; he was fine on glasses. I took a walk around the block. When I arrived back, a group of pretty young women had turned up, all of whom might have studied under Sally Bowles, and what seemed like the entire publishing world began to appear—Philip Roth, Truman Capote, Arthur Kopit, Jack Gelber, Norman Mailer, Terry Southern—all came parading in, one by one, a march of the literary greats.

Jules Feiffer became a friend, showing up regularly at our rental house on Fire Island. It took awhile for me to realize that the lure was not my company but the excellent cole slaw and potato salad prepared punctually at six each day by Mrs. Sullivan, a woman who looked after my sons that one summer of brief affluence. Or perhaps it was the handsome and 60ish Isabel Sullivan herself, who had once received a marriage proposal from Nelson Algren.

A door had opened. It wasn’t apparent at the time, but the trick was to get it to remain open. In a sense, the door never closes entirely. But I’m sure I’m not the only writer who has found himself eased out into the corridor from time to time, having to start the whole process over again.

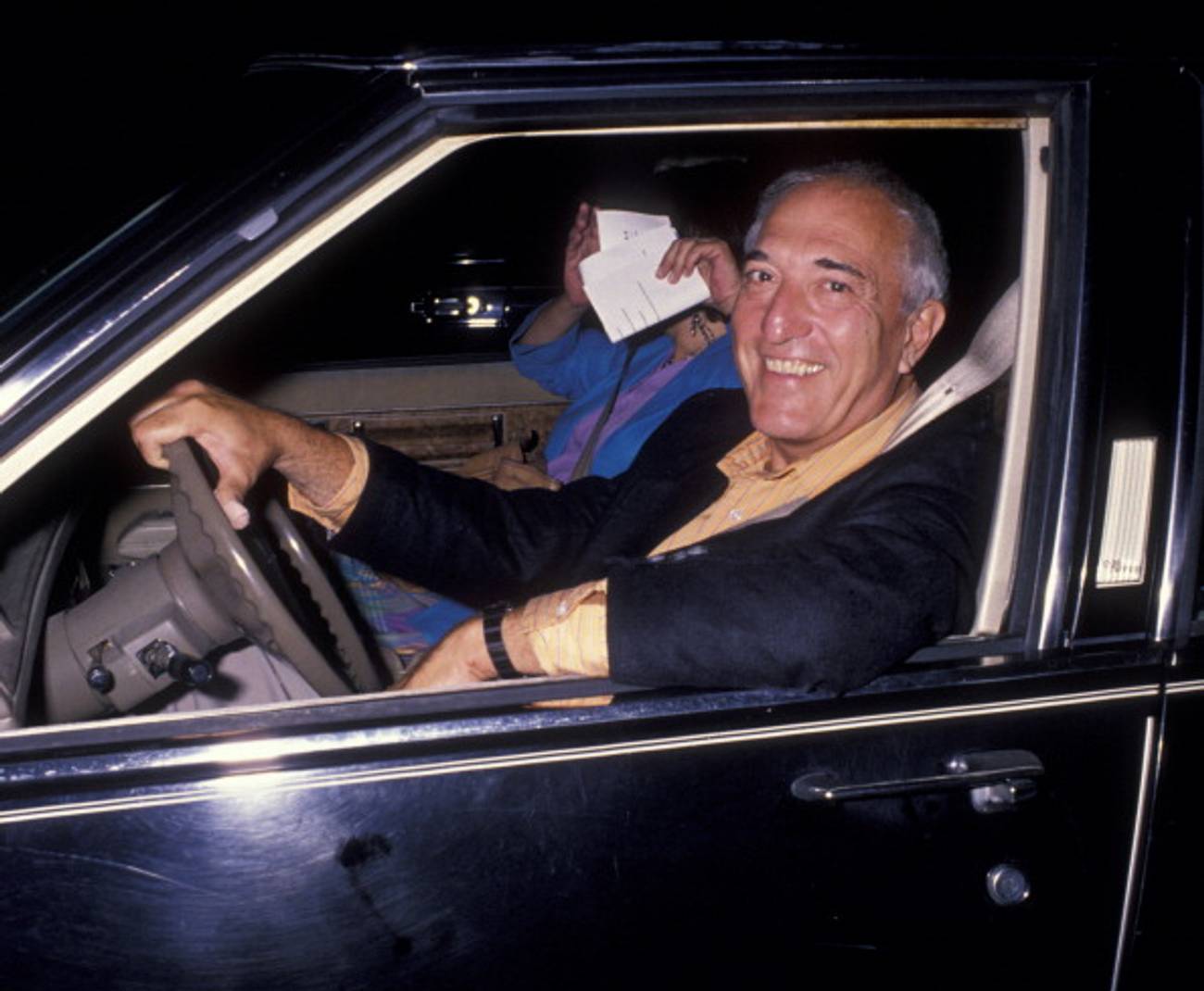

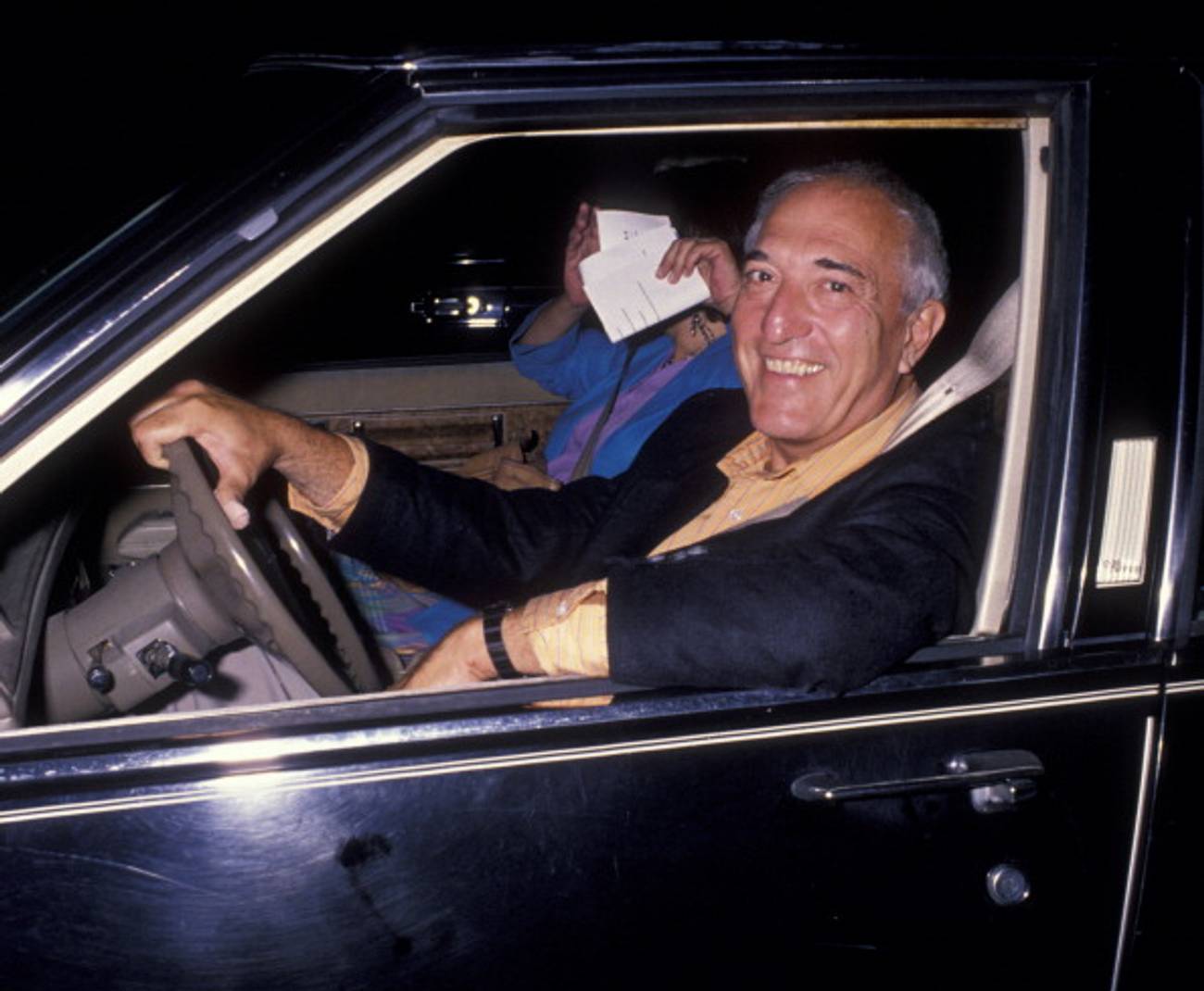

Bruce Jay Friedman (1930-2020), a novelist, short story writer, playwright, memoirist, and screenwriter, was the author of nineteen books, including Stern and Lucky Bruce: A Literary Memoir. His last collection of short fiction is The Peace Process. He died at age 90 on June 3, 2020.