It’s getting difficult to remember that Blacks and Jews once worked shoulder-by-shoulder to promote human rights and caroused together simply because it was such fun and they shared so much. Nowhere was that alliance more inspired than in the arena of jazz, and no maestros did more to encourage it than three of the genre’s greatest musical titans—Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong, Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington, and William “Count” Basie.

In his early years, Armstrong was as snakebit when it came to picking a manager as he was in choosing his spouses, of whom he had four. First up to oversee his burgeoning career was then-wife Lillian Hardin Armstrong, whom he stopped trusting to look out for his professional interests when their marital bonds unraveled in the late 1920s. Next came Tommy Rockwell. The brash record producer transformed Louis from jazz artist to pop star, but when he and his star parted ways on next steps, Rockwell goaded him with a pistol-packing mobster who left the trumpeter cowering in a phone booth. Johnny Collins, a nervous and nervy booking agent, promised to clean up the mess. The mustachioed manager did catapult his industrious client to greater success, but Collins went too far first by telling the music man not just where to play but what, then by assaulting him with the N-word. “Not that I haven’t been called a ‘nigger’ before,” an enraged Satchmo admonished the blind-drunk Collins as he was firing him. “But from you?”

All of which made the trumpet master rethink the counsel drummer and mentor Black Benny Williams had given him years before, in Jim Crow New Orleans: Always have a white man with his hand on your shoulder warning, “This is my nigger and can’t nobody harm him.” Rockwell and Collins were white, but turned out to be more Satans than saviors. Could Black Benny have gotten it wrong?

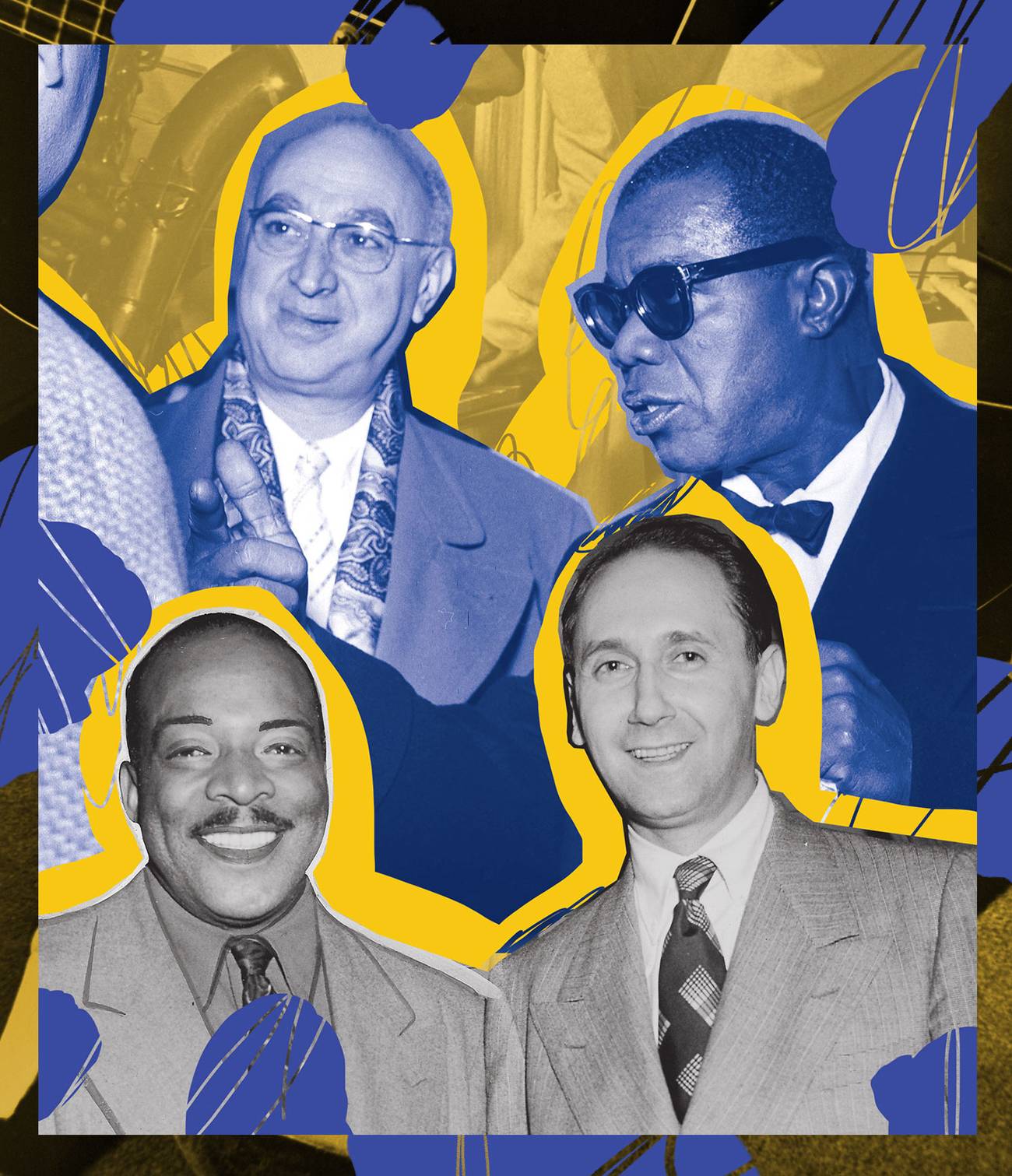

Louis’ third white man would prove to be his charm, unlikely as that seemed at the time. Bertha and George Glaser had hoped their son Joseph would become a doctor like his dad, and a cultured patron of Chicago arts like both parents. Joe made it as far as medical school, but was stopped in his tracks at the first sight of blood. Not long after he was running what he boasted was “the biggest chain of whore houses on the South Side of Chicago” along with a lounge that was a favorite watering hole for Al Capone and his mob. This being the time of Prohibition, police raided the Sunset Cafe on Christmas Day in 1926. The judge fined Joe $200 and pronounced his club “a public nuisance” after reviewing evidence that “girls of 17 were brought to the cafe by escorts and carried off the dance floor drunk.”

Glaser’s ticket back to solvency and respectability came courtesy of Black entertainers, and especially Louis Armstrong, who was as broke as Joe in 1935. Desperate for a manager to reset his career, Louis believed his best option was another white scoundrel. “I went to Papa Joe Glaser and told him I was tired of being cheated and set upon by scamps,” recalled Louis, who’d met Glaser years earlier. “I told him, ‘Pops, I need you. Come be my manager. Please! Take care all my business and take care of me. Just lemme blow my gig!’ And goddamn that sweet man did it! Sold his nightclub in Chicago where I had worked and started handling [me].” A handshake later they were partners, for life. Louis hated managing his bands or his business affairs. This new arrangement would make Satchmo rich and Glaser richer, and set a template for the wider world of Black entertainers and their white handlers.

The showbiz world didn’t know what to make of this oddest of couples: a foul-mouthed, middle-class Jewish kid from Chicago’s North Side looking for some South Side street cred, and a Black child of the ghetto eager for respectability. While their relationship was multilayered and not always on level terms, Joe Glaser meant it when he said of Louis Armstrong, “To me he’s like a son. A brother,” and when he told his most cherished ward, “Louis, you’re me and I’m you.” Louis, who grew up essentially fatherless, returned the compliment: “Askin’ me about Joe is like askin’ a chile ’bout its daddy.”

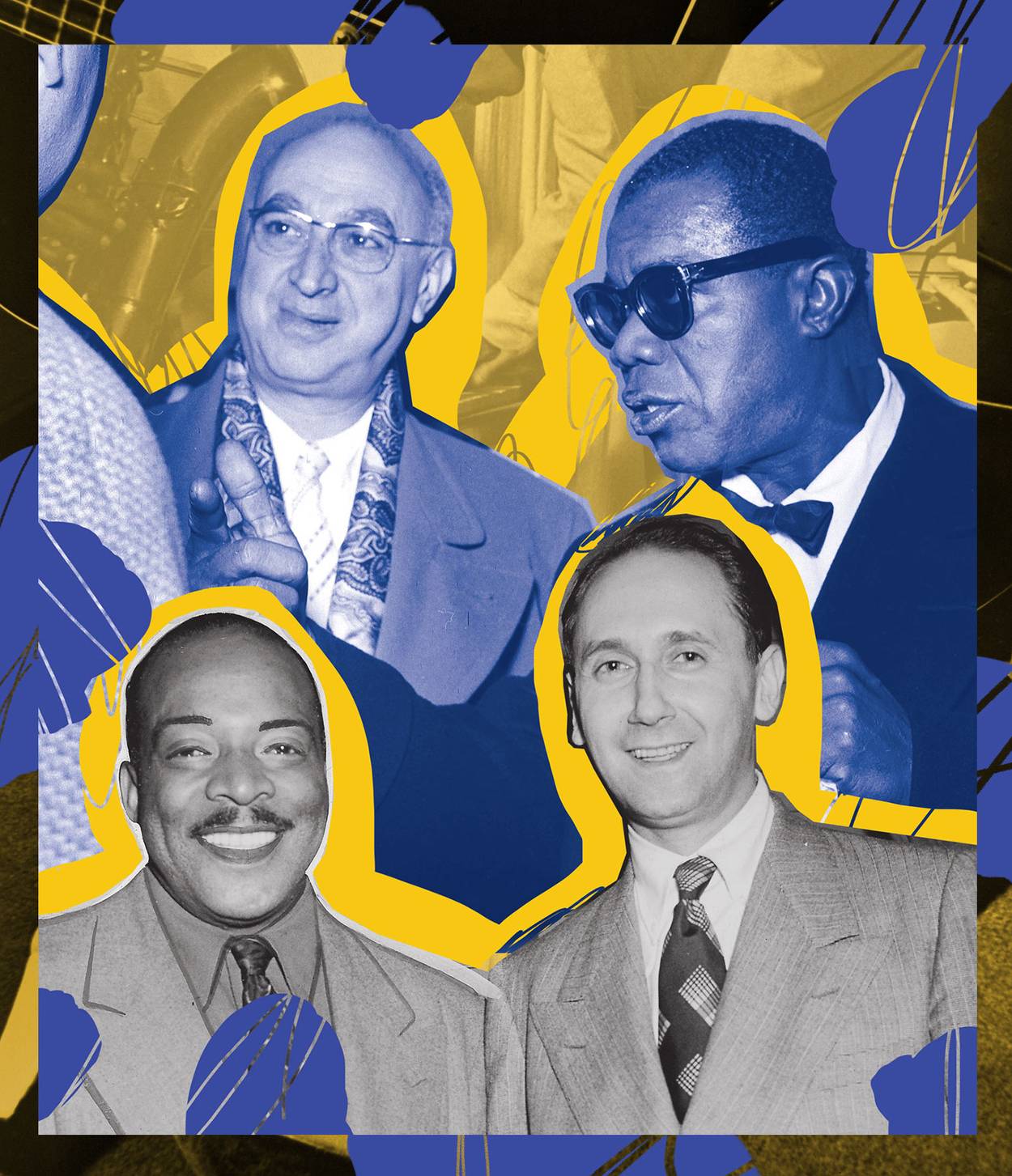

Irving Mills did as much to set the trajectory of Duke Ellington’s career as Joe Glaser did for Satchmo, although Mills didn’t last as long and was more of a spinmeister than a gangster. Mills had it easier because his client wasn’t a three-time loser when it came to picking managers, but Ellington did need handholding as he sought to break out of the big-band pack.

In Washington, when he was starting out in the early 1900s, Duke managed himself. He picked the tunes, booked the jobs, set and collected fees, and paid band members. He reached out with his era’s best marketing devices—newspapers and phone directories—offering “irresistible jass” for “select patrons.” While many of his patrons were indeed select—highbrows from the countryside with the time and cash for horse shows and fox hunts—others were urban and Black. He learned tricks like talking fast on the phone to make people think he was rushed. And he tapped his skills as a visual artist to run a sign-painting business on the side, then “when customers came for posters to advertise a dance, I would ask them what they were doing about their music. When they wanted to hire a band, I would ask them who’s painting their signs.”

He’d need more than his knack for hustling when he left the slow-paced and familiar capital in 1923, and headed to the fast-track, less forgiving Gotham. His first three years there showed his talents as a song writer and bandleader, but they required moving from club to club, then, when city residents cleared out for the summer, to mill towns and oceanside resorts in New England. The Washingtonians were known but not renowned. Duke seemed to have plateaued when, on a late night in 1926, he met Isadore Minsky—known then by the WASPy pseudonym Irving Mills that he bestowed on himself. In Mills’ colorful version, it was love at first sight when the dapper 32-year-old with slicked-back hair heard Ellington and his orchestra at the Kentucky Club, a cramped basement night spot in Times Square. A few days later Mills came to Ellington with a proposition: “How about doing records, Duke?”

The showbiz world didn’t know what to make of this oddest of couples: a foul-mouthed, middle-class Jewish kid from Chicago’s North Side looking for some South Side street cred, and a Black child of the ghetto eager for respectability.

Irving wasn’t an obvious choice. Small and squat, he had the limited vocabulary one might expect of a young man who was born in Odesa and grew up with Russian-speaking parents in the Jewish enclave of New York’s Lower East Side. There’d been little time for school after his father died, when Isadore was just 11. He lacked the toughness, or tough friends, that made Joe attractive to Louis, but also came free of Glaser’s penchant for underage girls and grown-up mobsters. Irving married at 21 and eventually had to support seven kids. He had a decent voice and an uncanny ability to re-imagine songs he’d heard. He plugged tunes by crooning them behind the music counter of Snellenburg’s Department Store in Philadelphia, nudging customers to buy, then for Broadway producer Lew Leslie, urging bandleaders to play Leslie’s verses.

More than anything, Irving was a go-getter with what his parents, Hyman and Sophia Minsky, would have called chutzpah. In 1919, he and older brother Jack started Mills Music to publish songs, and they soon progressed to producing records and scouting talent. He paid desperate songwriters $20 to $30, which was a lifesaver for the musicians and a steal for the Millses. With Duke, Irving said he knew from the first they could go great places.

He had a simple plan for the Washingtonians: Promote Duke not as a run-of-the-mill bandleader or piano player, but as a composer, an artist, and a genial genius. It wasn’t a hard sell because it was true, or would be soon. No one had ever tried making a pitch like that on behalf of a Black jazzman. Would the rest of the band, used to working collaboratively back when Duke replaced Elmer Snowden, tolerate Mills’ transparent bid to sideline their efforts as soloists, improvisers, and arrangers, and give all the credit to the bandleader-composer? And could Ellington really move from Negroes-only race records to the multiracial mainstream? Others had doubts, but not a natural-born fast talker like Irving Mills.

“When I got into the black thing, I figured I might as well corral something so that I could have control of something, and these people are appreciative,” explained Mills, who fancied himself the Abe Lincoln of the music world. “A dollar don’t care where it comes from, whether it’s black, green ... Everybody looked down at me. They said, ‘Geez, he fools around with niggers. Nigger bands.’ And just because I started this and it worked so good, all the other black people started to come around to me, all the best of them ... We were always ahead of ourselves.”

He stayed ahead, of his time and his competitors. He fed journalists catch phrases to describe Duke, including “Harlem’s Aristocrat of Jazz” and “the Rudy Vallée of the colored race.” He linked his commercial success to community-minded causes, letting it be known that Duke “will appear anywhere in behalf of a milk and ice fund, shoe fund, boys’ camp fund or any similar activity, or for the entertainment of war veterans, crippled children, aged persons or other hospital shut-ins.” He and Duke burnished the Ellington resume, suggesting that the bandleader had graduated from high school and attended a conservatory.

Mills’ industriousness paid off big. Prior to 1930, Duke’s name appeared a mere 15 times in the national edition of the Chicago Defender, America’s leading Black newspaper. From then until 1935, with Mills overseeing a stable of publicists, Ellington was mentioned there in 284 separate stories. By branding his client as a philanthropic artiste, and incessantly hyping him in the press, Mills got Ellington into Harlem’s jazzy Cotton Club. He secured unmatched national radio play and singular tours here and abroad from the Roaring Twenties into the Threadbare Thirties. The band grew as did its record deals and booking fees. Irving knew what the public wanted and he and Duke delivered. Yes, that meant “jungle music,” with light-skinned, barely clad chorus girls. Yet along the way, Irving and Duke—whose complexion The New Yorker described as coffee with a strong dash of cream—loosened those restrictions. Theirs was the first Black ensemble in a major Hollywood feature, the first in a Ziegfeld show on Broadway, and, in time, the first to replace jungle with genius as its marketing master plan.

It was no surprise that Mills, Glaser, and so many other managers of Black jazzmen were not just white but also Jewish. Jews always played a big role in jazz, as performers like Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw, club owners like Frank Schiffman at the Apollo and Max Gordon at the Village Vanguard, gangster benefactors like Dutch Schultz and Meyer Lansky, along with a legion of producers, bookers, and critics. Jews, like Blacks, had limited opportunities in white-shoe fields like advertising, publishing, and broadcasting. Such barriers are what made the equally rebellious field of comic books so attractive to Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster and Batman inventors Bob Kane and Bill Finger, all Jewish and all aware they were getting in on the ground floor of a rapidly growing and super-profitable field that white American businessmen foolishly wanted no part of. Blacks and Jews also shared long and rich histories of music as an outlet or escape in repressive circumstances.

Count Basie’s first and most influential manager didn’t fit that mold. John Henry Hammond was less of a handler than a spotter, enabler, producer, and critic. He hadn’t risen from his bootstraps and wasn’t street smart. A Yale dropout, he’d grown up in a Manhattan mansion with a houseful of servants, private schools including St. Bernard’s and Hotchkiss, and a lineage that included great-great-grandfather Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt and a namesake father who worked as a banker, railroad executive, and lawyer. Though from an establishment WASP family, John II always purposefully identified with underdogs, especially Jewish ones. He searched for Hebrew ancestors and told people, “I wanted to be Jewish.”

Hammond eventually yielded to more full-time and professional managers. Basie turned first to MCA, then to the William Morris Agency. As with Duke and Satchmo, the Count’s most trusted managers and business partners going forward were Jewish—including Milt Ebbins, who helped lift him out of debt; Sam Weisbord, a honcho at the Morris Agency, and the fierce-tempered, big-as-a-house hustler Teddy Reig, who produced some of the Count’s best records.

It wasn’t just the Count’s, Duke’s and Satchmo’s managers and bandmates who were Jewish, but their friends and enablers. Armstrong was a proud pothead nearly all his adult life, lovingly referring to his drug of choice as gage, muta, pot, and “that good shit.” And his supplier of choice was the notorious dealer and clarinetist Mezz Mezzrow. Born Jewish as Milton Mesirow, he married a Black woman, moved to Harlem, declared himself a “voluntary Negro,” and listed Negro on his draft card. Mezz’s name became slang for marijuana. “I’d like for you to start right in and pack me enough orchestrations to last me the whole trip,” Satchmo wrote Mezz from the Queens Hotel in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1932. He wasn’t, of course, talking about music scores. But he was clear where he wanted the cache sent: “to the American Express Company, Paris, France. If you mail it now, it’ll about get there the same time as me. No doubt you’ve received the money I wired you, eh?”

Armstrong’s connection to Jewish people was about more than money, dope or even music. He considered them to be his family. The jazz titan began the last of his four memoirs, Louis Armstrong + the Jewish Family in New Orleans, La., from his hospital bed in 1969: Inspired by the Jewish doctor who’d just saved his life, it was dedicated to his Jewish manager Joe Glaser, who died at New York’s Beth Israel Hospital at the same time Louis was being treated there. The handwritten 77-page document was mainly a tribute to the Karnofsky family of Lithuanian Jews who, like other Jewish refugees, supported their dozen-strong family by picking up work more established immigrants didn’t want. That meant peddling rags, bottles, and bones, hawking stone coal, and selling secondhand clothing and hardware. They also took in a 7-year-old Black orphan.

Louis proudly recounted opportunities the Karnofskys gave him to venture into otherwise verboten white Storyville to try out his first musical instrument, a 10-cent tin horn that, along with his singing, attracted rag buyers; to break with them Tillie’s challah or matzo, then listen to her soothing Russian lullabies; to hear the prayerful davening that would help inspire his nonsense scat singing; and to be embraced by the first white family he knew close-up, who “kept reminding me that I had Talent.” He acknowledged them not just in his writing—“I will love the Jewish people, all of my life”—but by wearing a Star of David around his neck for the rest of his life.

Can such bonds be reforged at a time when the fighting in the Middle East is, back in America, pitting these two communities of outsiders against each other? Perhaps not. On the other hand, the bonds that united Blacks and Jews at the height of the Jazz Age were less a matter of the politics of the moment than of deeply rooted historical suffering that bred a shared sympathy as well as great art.