Clearing a Space

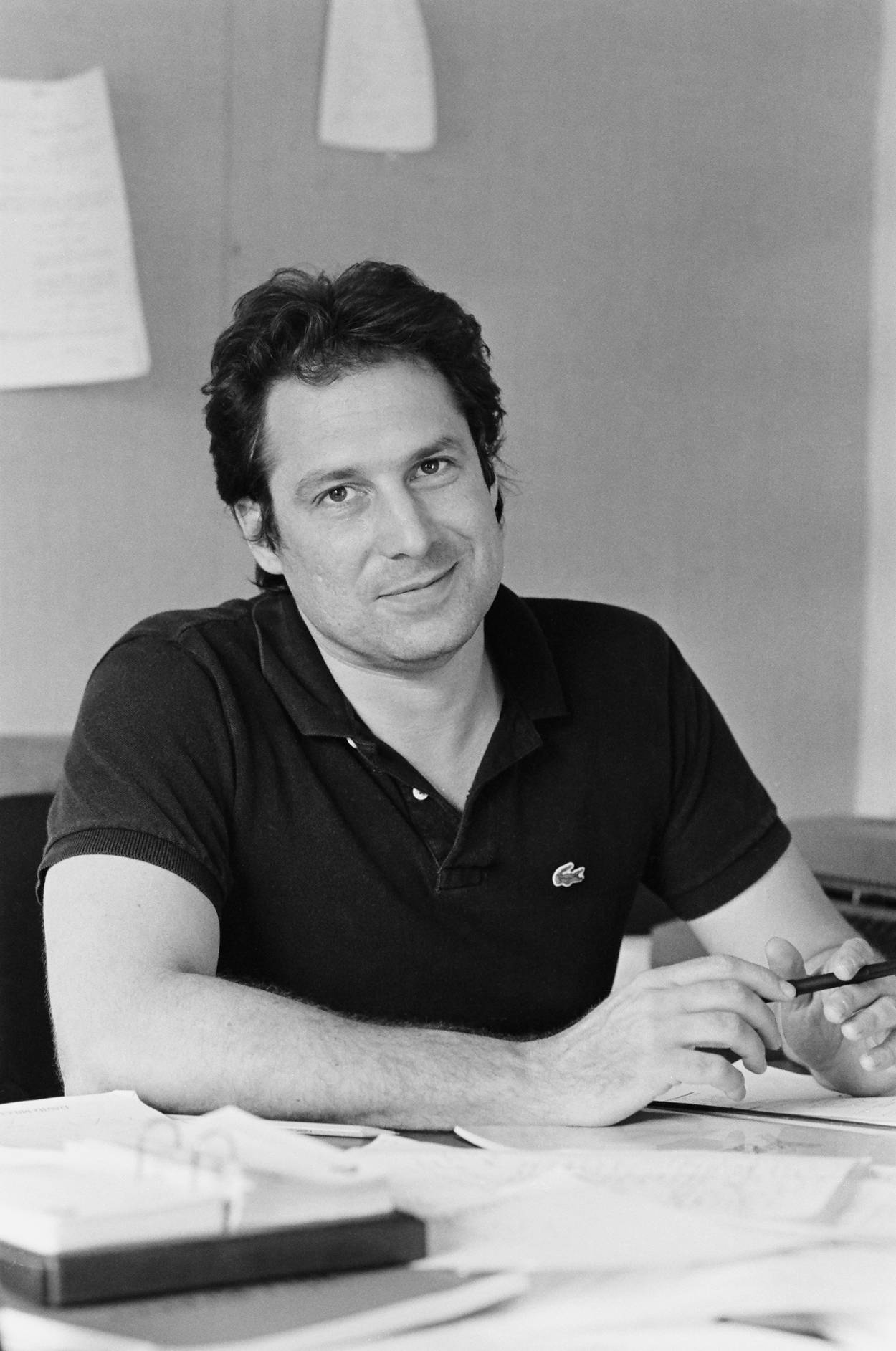

David Milch is the genius behind shows like ‘Deadwood’ and ‘NYPD Blue,’ with fundamental insight into the crooked workings of humanity, and the human soul

“Clear a space,” David Milch would say, and the script coordinator or the assistant assigned to transcribe Milch’s dictation would hit the return on the keyboard at their desk, creating a blank space on Milch’s monitor, empty of all words and images and any trace evidence of prior creations.

Milch has a chronically bad back. He lies on the floor as he works, surrounded by annotated script pages and printouts of the current draft of his work in progress, weaving stories in and out of each other in midair. He performs this work before a silent audience of aspiring writers; paid interns, for payroll purposes.

Milch is a friend and professional colleague I’ve had the good fortune to work with many times over the last 40 years. He has written and produced hundreds of hours of popular dramatic entertainment, initially for broadcast TV, later for the cable network HBO. Milch’s shows, like NYPD Blue, which he created with Stephen Bochco, and Deadwood, were popular and commercially successful, but they were even more influential than their popularity would suggest, often appealing to those who don’t normally watch popular media. I loved working with David, not only because he was a line-level genius, but because of his insight into the crooked workings of humanity, which he understood fully, with love.

There’s no guarantee of popular success for writers, especially writers of genius; writing is a calling, a vocation. For some, it’s a curse. It’s not a choice, except for the hobbyist. In David Milch’s case, his survival depended on the work, and the work depended on prayer.

Other writers and journalists often asked Milch about his “process,” or writer’s methodology. Writing is a mixture of craft and inspiration around which professional writers often construct elaborate superstitious rituals, just as athletes frequently do. Milch always replied truthfully that his “process” was his reliance on prayer.

Prayer is indispensable to Milch in his work and in his life. Milch works every day, and he prays every day. His sense of the possibility of a world beyond the one we see on an everyday basis is essential to his art, and to his judgments of men. Even his memorably foul-mouthed demystifying creations like Andy Sipowicz on NYPD Blue or Al Swearengen from Deadwood, who were so often taken as Milch’s own alter-egos, were in constant conversation with the beyond. Inventing characters, he knew whether the soul of a man had passed through previous transmigrations or whether it was one of the “new souls.”

As a result of birth, his genius, and despite, or because of his sexual abuse, Milch was destined for a top spot in the mirror world. He might truly have run nations, operated vast covert financial networks, made and broken lesser men. He could have created and captured industries. The kingdoms of the world were on offer, in line with the capacities that were his birthright, and which had been nurtured in him by the traumas and other advantages of his upbringing. Instead, Milch felt called to the work that would save his life, and which benefit our world in ways most of us are unable to really see.

David Milch’s father was a prominent Buffalo physician—a surgical innovator, the respected and successful head of his department at the principal hospital of that then-thriving upstate city. Milch’s mother was, according to her son, politically progressive. During his childhood, she was occupied with the improvement by education of the lot of working people; as head of the Buffalo school board, she was preoccupied with that task.

Many of Dr. Milch’s patients were “successful Buffalo businessmen” who had prospered greatly in prohibition, and after WWII, were actively engaged in the modernization of bookmaking, loan sharking, prostitution and new gambling enterprises in Havana, Cuba, and later, after Cuba’s revolution, with building Las Vegas. Milch recalls his childhood home as often filled with convalescing gangsters under Dr. Milch’s care. He also noted that their delicate cardiac conditions often correlated with congressional hearings on organized crime, which the convalescent wiseguys watched with much amusement, their comments providing an education for the young boy in the ways of the real world. “I had one great-uncle we had to visit outside territorial waters on a boat off Florida,” he recalled. “There were certain members of the family who would never be seen in public with my dad—not because he objected, but because they didn’t want to screw him up.”

In 1950s Buffalo, the rackets were a career so lucrative, open and accessible to all, that the work was, if not respectable, a lesser disgrace than being poor. When Meyer Lansky said, “We’re bigger thant US Steel,” he was being modest. If you were part of the world of OC, the mirror world, by birth or elective affinity, you knew cops and crooks were not opposite poles of a moral continuum, but rival predators. (Anyone familiar with the horrendous Whitey Bulger case in Boston will recall how the FBI partnered with Bulger’s criminal faction to wipe out the previously dominant Italian mob.)

Milch was a child prodigy. He could read, understand and remember books, songs, faces, numbers, images, and stories. He never forgot anything, a trait that was perhaps not always to his benefit. Milch often tells how, in his childhood, a “family friend, a friendly uncle type,” introduced him to a “gang of pedophiles who passed me around from the time I was 8.” Even if most people prefer not to think about it, the trade of children is a lucrative feature of the mirror world, and the building of pedophile blackmail/control networks is the meat-and-potatoes of every intelligence service.

“The pain of the past in its pastness is translated to the future tense of joy,” David Milch liked to say, quoting the great American literary figure, poet, author, and teacher, Robert Penn Warren, Milch’s mentor at Yale. Milch had a spectacular undergraduate career at Yale. No undergrad in living memory is recalled by his peers as so brilliant, so charming, so candid, so amusing and so fucked up. Milch graduated first in his class. Of Penn Warren, Milch said, “He saved my life, just in terms of showin’ an example of how to live a coherent life. He also engaged me to work on a history of American literature. ‘I can’t help you,’ he said, ‘until whatever is troubling you remits itself, but you can study during this period.’”

At Yale, Milch was a member of the same fraternity of which George W. Bush was president. The other brothers were the patrician, moneyed sons of established WASP families. Whatever the qualifications are for a cabinet post in the Underground Empire may be, David Milch, a Jewish doctor’s son from Buffalo, met them. Once, on a duck hunting trip to Louisiana with some fraternity brothers, Milch was sitting in a swamp, slapping flies and attempting to avoid injuring any ducks. He felt a hand on his shoulder. It was a friend’s father, then director of CIA, later president himself, who’d joined the hunt. “You’re a good Jew, Dave, you’re a white Jew. I like you,” George H.W. Bush blessed him.

David Milch, whose mother ran the Buffalo school board, whose father tended to gangsters’ hearts, and who was passed around by pedophiles as a child, was invited to join the most storied of all secret societies, Skull and Bones. There is a procedural ritual. The invitation is formally made and the candidate advised the only responses accepted are one word, either “accept” or “decline.”

Today, Milch’s fraternity brothers run Fortune 500 companies, intelligence agencies, and foundations which bend dreams into shapes that fit together in ways that the so-called beneficiaries can’t see, but the grant-makers can. A tremendous opportunity for a (relatively) poor but talented Jewish child from soon-to-die Buffalo to have power and make money. Milch declined.

Milch tells a story about a bachelor party in Houston, which perhaps may shed some light on that choice. Milch and several of his fraternity brothers were invited to the wedding of another frat brother. The family jet of the future groom flew the groom’s party to Houston for a week of pre-wedding festivities. The high-spirited youths were each given Mercedes to drive, compliments of somebody’s father’s dealership. The future operators of the world all got drunk and they took those Mercedes off-road, onto a golf course and had a Paris-to-Dakar rally on the local country club greens and fairways. You can imagine there was heck to pay, and quite a bit of shouting. In the end, somebody’s father had to pay for the extensive landscaping that was needed to restore the Bob Rees’ golf course.

Then came the night before the wedding, and the groom was asked, “is there anything special you’d like to do on this, your last night of freedom.”

The groom replied he’d like to destroy an original work of art.

After a brief scavenger hunt, a Chagall drawing was located and ceremoniously incinerated in the wastepaper basket in the library of a Houston plutocrat’s home.

There are mystics who believe it is wrong to retain beyond the immediate needs of self and family, riches that flow from a freely given gift of God. I don’t know if Milch believed that. If he didn’t, though, his lack of such faith could not be told from his behavior. David Milch made large amounts of money, but he gave it away almost as fast, constantly, in private and in public, making no distinction in persons on religious, racial, economic, or public health grounds, as long as they would share in his wealth.

Milch helped friends, relatives, friends of relatives, friends of friend’s relatives, and thousands of strangers. He eased countless family emergencies, helped with hundreds, perhaps thousands of substance abuse disasters, broken cars, burned homes, dead batteries, and felony warrants. Milch was a source of unsecured, no-interest, often no-repay “loans” to the worthy and unworthy alike.

Milch’s beneficiaries, erstwhile creditors where they had the brains, would find his advice more valuable than money. Rita, nee Rita Stern, David’s long-suffering wife, would periodically purge the charitable rolls, evicting excessively tenacious clients. However, Milch is an earnest member of several recovery communities, which continuously provide an ethnically diverse multitude of worthy and unworthy persons in indubitable need.

Milch, under no illusions, loves them all. He loves the scamps, the wiseguys the perverts and fools, Mormons and Mormon-haters, good and evil; though the latter tended not to hang around long, due to Milch’s long friendship and professional association with NYPD Detective Bill Clark. Milch’s only close male friend in adult life, Clark is an Irish American Vietnam vet who began his career in NYPD’s (then secret) Intelligence Division. On patrol in the jungles of Southeast Asia, Clark developed an eye for hidden trip wires and booby traps. As head of a big city homicide division, Clark’s work involved handling hot cases, politically dangerous cases, involving powerful people and terrible secrets. Many of the stories on Milch’s NYPD Blue police drama originated in Clark’s case files.

David Milch’s own celebrated descents into the world of addiction, compulsions, and the demonic occurred at long intervals separated by decades of productive work. The experiences informed his dramas, as did his childhood experience of sexual abuse. He elevated with love that fallen world, this realm with its multitude of addicts, golems, killers and demons inhabiting the walking wounded of diminished capacity. All dramas begin, “Back,“ Milch would quote the poet William Yeats, “where all the ladders start; in the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.”

Besides opiates and the rest of pharmacopeia, Milch suffered from another, more dangerous addiction: high stakes gambling. He owned racehorses, and won the Breeder’s Cup Juvenile back in 1992 with the beautiful filly Gilded Time. For this reason, he was hesitant about doing the dramatic series Luck, a story about organized crime and revenge set in the mirror world of horse racing.

In gambling parlance, David Milch was a whale—a high-net-worth individual who meets the definition of hope-to-die gambler, an addict who, once he “gets his nose open,” will make million-dollar bets and find it difficult or impossible to stop. Las Vegas bookies offered a million-dollar cash reward for anyone who delivered Milch as a client.

What we know, for sure is that in the end, the house wins. Perhaps the mirror world takes the money back, or a beat forces the gambler to reflect on who he is and what he wants. “We let you walk around like a man for a while, then we turn you back into a little boy,” is an old Vegas saying Milch liked to quote. Milch lost, they say, $70 million. I wasn’t there and did not discuss his losses with him; we mutually acknowledged those facts through silence. It was a bad beat.

Milch wasn’t quitting, though. He thought he might have one arrow left in the quiver. He talked about a show set in a CIA-run bordello in London. The players were Sir James Goldsmith, several Rothschilds and Guinnesses, Lords Aspinall, Lucan, and a spectrum of addicts, occultists, extortionists, and spies engaging in espionage, extortion, entertainment, political blackmail in the treacherous hypersexed milieu of the London clublands.

We were driving to lunch in Santa Monica, discussing the prospective CIA project one afternoon, when Milch said he’d made an appointment with the former director of the CIA, James Woolsey, to meet at the LA airport to discuss the projected U.K. spy-honeypot project. An important meeting, a necessary conversation. Milch was to meet the former director between planes in the not-so-secret VIP spook lounge at LAX, when something entirely unexpected happened.

“I forgot,” he told me.

David Milch didn’t forget anything. Ever. We both knew that. If he forgot anything, it was a sign of something awry, an ominous warning of pathology at work. In retrospect, Milch recognized there had been other warning signs. It wasn’t long, perhaps a week or two, between that conversation and Milch being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, a progressive dementia for which the only treatments are palliative. “It’s not scary,” he said soon after his diagnosis, “it’s just like … the world slipping away.”

A bad beat. And yet, Milch had rejected the position on offer. He declined membership in the semisecret club, did not sleep naked in a tomb with a stolen skull; instead, by prayer, personal sacrifice and constant lifelong effort, he created redemptive works of dramatic art.

The worlds of Deadwood, of NYPD Blue and John from Cincinnati and every other dramatic world that Milch created stood opposed to the pure materiality and marketing of the mirror world. The economic and popular success Milch’s shows enjoyed was outweighed in importance by the powerful and enduring effect on human consciousness of thousands of hours of dramatic entertainment which showed, and which itself is, a work of the spirit.

Prayer is how David Milch thought about his work, and stages of contemplative ascent occur in sequences of scenes. For some, an eschatological elevation of the soul occurs unexpectedly. While Milch always identified himself as a Jew, like another old friend, Kinky Friedman, he is somewhat estranged from traditional, formal practice of Judaism, as I am from the Anglican faith of my birth. My own interests and our irreligious times inclined many of us, “Christians, Jews and Sigma Nu’s,” as Kinky Friedman likes to say, to a semi-agnostic secularity that did not frown on prayer or the possibility of redemption. Once a fellow writer described the deity in Milch’s presence as “the foul demi-urge that made this world.” Milch was profoundly shocked. Not much shocked him, but his face showed unmistakable horror.

Milch was able to look with love on all the polar extremes of experience, a capacity that is especially necessary and lacking now, as times are changing. The world has a way of opposing and mistreating unusual people while the person is in the body, and so it is better they remain anonymous while within the world’s reach. When they are beyond it, as David Milch now is, it is better their works be known. He was the “Rosh ha-Dor, the leader of his generation, in the spiritual sense of the person who lives in communion with God, but utilizes his power in order to draw his contemporaries upward with him.

Ted Mann is an Emmy award-winning writer who worked on NYPD Blue, Deadwood, Hatfield McCoy, and Homeland.