Is Being Essentially Jewish?

The poet Benjamin Fondane sought to hold God accountable for a confusing, alienating world

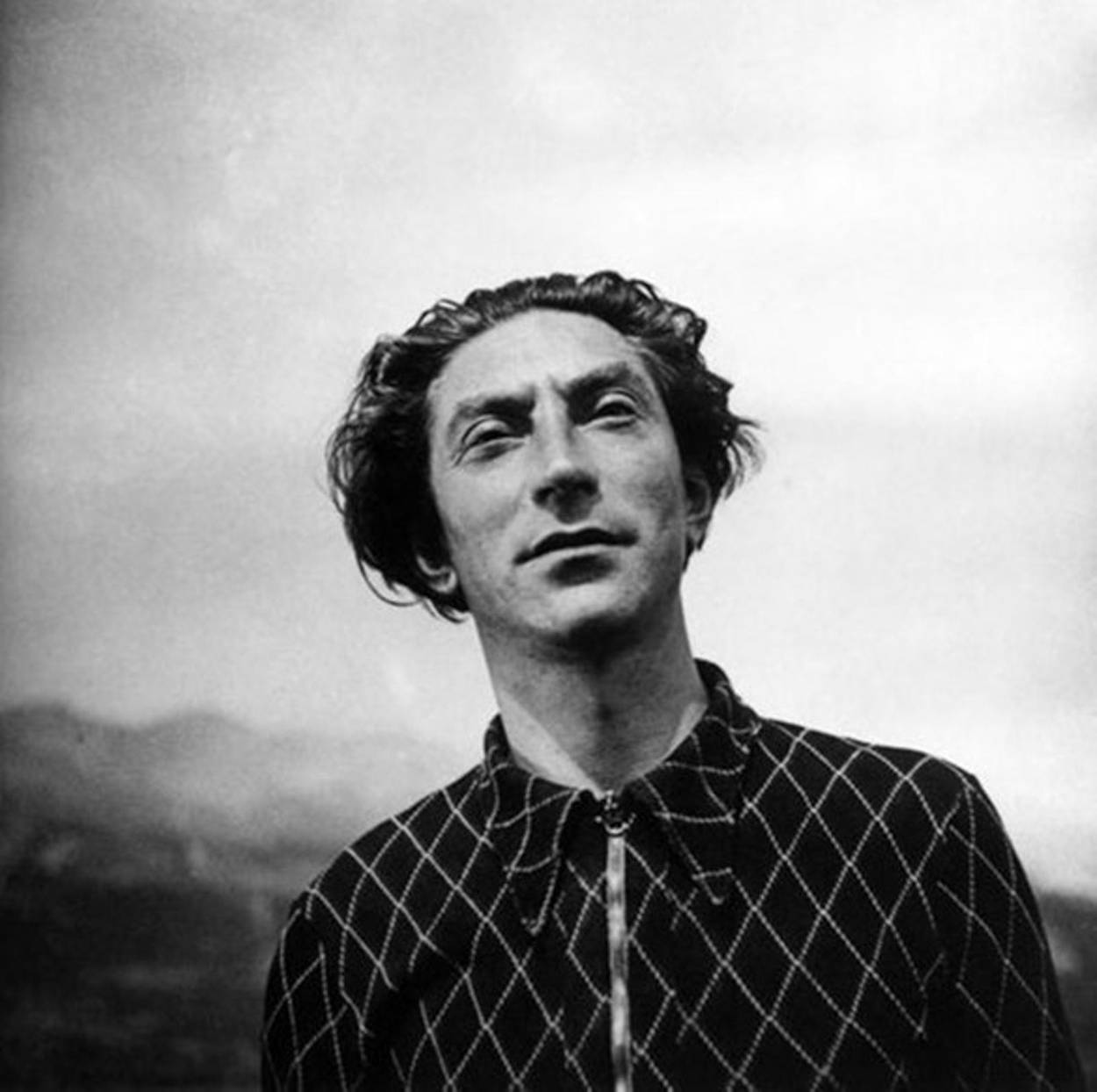

In what was supposed to be a short essay celebrating the 70th birthday of Lev Shestov (titled “In Search of Lost Judaism”) the poet, playwright, screenwriter and philosopher Benjamin Fondane (1898-1944) began by declaring his mentor to be “essentially Jewish.” But the essence of Jewishness, he continued, has nothing to do with “geographic, historical, or national” characteristics that marked Jews as a distinct community.

Being essentially Jewish, Fondane claimed, means being open, even “against one’s will,” to “a revelation” from the Bible. By this definition, the Christian philosophers Pascal and Kierkegaard, who called on the “God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob,” are more Jewish than secular thinkers like Freud. Indeed, they are more Jewish than Maimonides, “who asked us to interpret the texts of Scripture according to our own reason” rather than in a conversation—and confrontation—with God.

Fondane’s argument recalls Lenny Bruce’s routine, “Jewish and Goyish,” in which the comedian spins stereotypes around until their contents blur (“Ray Charles, Jewish ... B’nai Brith, goyish”). But if Fondane was perhaps exulting in his paradoxes, he nevertheless meant just what he said. From the early 1930s until his death at Auschwitz on Oct. 2 or 3, 1944, Fondane used eclectic sources to pursue an incisive spiritual questioning that sought to hold God to account for a disorienting and unsurvivable world. His poetic and philosophical work is one of the peaks of modern religious thought and a wrenching, personal demand for answers to the questions that remain essentially Jewish and essentially human.

Fondane developed his ideas in poetry as well as prose, and in considerations on the shared disasters of history as well as the secret cravings of our hearts. It is only recently that studies by Bruce Baugh and Michael Finkelthal have made some of Fondane’s ideas available to English-speaking readers. The advantage of this relative historical neglect is that Fondane can be read as he read others—not as an intellectual technician making interesting moves in a scholarly game, but as an individual asking the most vital and enduring questions, which are, inevitably, questions about and addressed to God.

Fondane was born in 1898 to a prosperous family in Iasi, Romania’s second city. At the age of 20, he moved to Bucharest, ostensibly to study law, but in fact to become a figure in avant-garde literary circles. He published a staggering quantity of poems, plays, and articles over the next five years. To the consternation of many of his colleagues, Fondane argued that Romanian literature, from its 19th-century classics to the radicals of the 1920s, was nothing but a series of imitations of French originals. At 23, he left for Paris.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the French capital was a center of cultural innovation and of overlapping diasporas. Fondane’s social circles included fellow Romanians such as Tristan Tzara and Emil Cioran. The Argentine writer Victoria Ocampo took him under her wing, bringing him twice to Buenos Aires, where he lectured on surrealism and directed the musical comedy Tararira. But Fondane’s most important influence was Shestov, a Russian Jewish émigré, whom he met in 1926. One of the fathers of French existentialism, Shestov argued that 19th-century thinkers like Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Dostoevsky had outlined possibilities for a new kind of philosophy that saw the personal, emotional, and irrational dimensions of human life not as distractions from clear thinking, but as that which most needed to be clearly thought.

Under Shestov’s influence, Fondane became a philosopher in his own right. He elaborated his ideas through critiques of other thinkers and through poetry, never erecting a formal system. To contemporary academic philosophers, he may seem to offer no new concept, no distinct moment in the history of thought. He had no students and did not invent a “Fondanian” style that could be imitated by others. In a 1933 essay, “Soren Kierkegaard and the Category of the Secret,” Fondane wrote of the Danish philosopher, but no less of himself: “Unhappy with this reality, he demanded to speak to the Manager ... But there was no Manager. To whom could he complain?”

Asking to speak to the manager may not strike readers as a deeply spiritual act—nor may it seem pious to say that God, the Manager of reality, does not even exist to receive our complaints. For Fondane, however, to be essentially Jewish and to be authentically religious meant speaking to God, even in the mode of complaining and even in spite of His apparent absence.

Fondane’s attitude has as little in common with the everyday sense of “religion” as his list of “essential” Jews does with ordinary understandings of Jewishness. But, Fondane insisted, each of us has the freedom, or the responsibility, to use concepts in a personal way, “to put ‘his own drama’ at the heart of the philosophical problem.” Rather than asking, for example, in the broadest possible terms why bad things happen to good people, why evil and suffering exist, etc., Fondane would have us ask why—and indeed complain that—bad things happen to us, specifically.

As Fondane saw it, the “philosophical problem,” the problem that both initiates and exhausts all philosophical questioning, is that what happens to us is not only “bad,” but “specifically” our own. What happens to us—our experience—is a “secret” that we can never share with others and can hardly even share with ourselves. To contemplate this secret, for Fondane, is to be led into a confrontation with God, who is the same kind of secret that we are.

Fondane illustrated this point with an apparently pointless question, “Can we have a body?” The answer would seem obvious, but as he described the body it becomes less so. Our body, he observed, “desires, loves and wants to be immortal.” Here, then, “the body” means not just our flesh, but the affects that inhabit it and make up our embodied “Ego.” The body is what is uniquely our own, that which makes us a distinct, irreplaceable person instead of a fungible instance of rational being. But it seems impossible for us, insofar as we are rational beings, to “have a body” in our thought, to use concepts to understand our embodied experience in its radical singularity.

God, Fondane argued, is absolute, unique, and unknowable in terms of our concepts. A concept discloses the common features of whatever phenomena it names together. Everything that passes through concepts, therefore, seems stripped of its particularity, and insofar as it depends on concepts, rational thought of any kind “runs the Ego through a shredder.” If we use concepts to think about our own experiences, from the most everyday sensations and transient feelings to the most intense states of ecstasy or despair, we will find ourselves representing them as abstract, impersonal conditions that could have happened to anyone. We will miss what it was that happened to us, specifically. Yet if we try to think about ourselves as distinct individuals without using concepts, and thus falling into “the general,” we will only encounter a “perpetual failure” of thought.

It would be tempting, then, to become “a person without a body,” only experiencing ourselves through the categories that we share with everyone else, imagining that we can explain what matters about ourselves in those socially available terms. We could thus “make a confession, open ourselves, rejoin the general.” But in doing so we would not only lose our body, but also God, who “speaks only to the individual,” to just that particular embodied person whom conceptual thinking fails to grasp.

God thus has something important in common with our body, with our own particular physical and emotional sufferings and longings, which also cannot be rightly apprehended through concepts. Religion, rightly understood, is the relationship between the unthinkably finite body and the unthinkably infinite God.

Between these two incomprehensible singularities stands not only the interference of rational thought, with its generalizing concepts that reduce God and the body alike to mere ideas, but also religion in its ordinary, inadequate sense. Religions gather believers together around concepts, disguising the essential “powerlessness” of each person’s efforts to think their life or their relationship to the absolute. Religious leaders give believers the impression that when concepts are uttered, “someone is speaking and solitude disappears,” that our inexplicable, bewildered and utterly lonely existences can be made sense of together in a shared vocabulary.

For Fondane, God has nothing to do with such religions. He does not speak to us in order to “organize human societies ... for their greater happiness” through universal rules and common ideas but to summon us, each individually, to see how our wordless confusion that can find no satisfaction in the world, and our philosophical problem that can find no answer in philosophy, drive us out of the world, out of philosophy, out of merely human religion and out of concepts, towards Him.

Like his philosophy, Fondane’s poetry is only now becoming familiar to American readers, thanks to Leonard Schwartz (editor of Cinepoems and Others, a collection of translations of some of Fondane’s most important poems by translators of varying skill) and Nathaniel Rodavsky-Brody (who has, masterfully, translated Fondane’s poem cycle Ulysse). What follows is a brief introduction to, and excerpt from my new translation of Fondane’s long poem Exodus: By the Rivers of Babylon (L’Exode: Super Flumina Babylonis).

Written in 1934, Exodus was edited a decade later for inclusion in what Fondane intended to be his collected poetic works, a volume titled The Ghostly Illness (Le Mal des Fantômes). The original poem was a meditation on Psalm 137:4, with the question, “How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?” serving as a reminder of the Jewish exile in the Babylonian empire and throughout history: “By the rivers of Babylon we sat down and wept/many rivers have flowed through our bodies already/many rivers where in days to come, we’ll weep.”

As the poem continues, other rivers appear, from the Nile to “the Mississippi ... where God has been wandering,” each the scene of suffering and injustice. In the middle of the poem, Fondane further universalizes the theme of exile, asking how any of us, at any time, can sing. He insists that the human condition is not a contingent, historical exile that consists of happening to be “a stranger in a stranger land,” but rather being necessarily out of place as “a stranger to himself/whose home is not on earth.” Just after these verses, Fondane inserted a long “Interlude,” written in 1942-43, for the final version of the poem included in The Ghostly Illness.

The “Interlude” is an account of France’s defeat in 1940 and the attempted “Exodus” of civilians fleeing the German army. It shuttles through genres: plaintive lyrics addressed to French rivers, Whitmanian catalogs of dead soldiers, and imprecations to God as forceful as those of the biblical prophets. But when the first eight stanzas climax with an appeal to Heaven, God does not respond. The “Interlude” ends with no survivors or explanations, after the disappearance of “the world” of human life. Writing in occupied Paris, stripped of his French citizenship and foreseeing his death, Fondane refused to be consoled by illusions of salvation—or to cease calling on God.

Interlude

The Wrath of Vision

1

And I said to my vision: “so what’s Exodus?

what’s Babylon, and what’s Jerusalem?”

If there’s no river running through and underneath the world,

invisible, beneath the times that seem like peace,

if no one’s watching over all the leaves that fill

the wood,

if human screams fall to the ground like chestnuts

shaken by the wind,

and leave the peace of angels undisturbed,

what’s Exodus?

What is it

if it isn’t something ever-present?

And then I was cast down into the countryside of France.

2

Disaster fell upon our weapons

on the Seine and on the Loire. The Meuse screamed

“Flee!”

We fled as suddenly as fall’s red rains

we gurgled through the gutters

of the roads

we came from Arras and Amiens

we came from Reims and Lille

Tourcoing, Rouen

a storm of carts and trucks

We slept on horseback like bronze kings—

our faces lit with flashes of exhausted rage.

3

Scream, oh door!

Cry out, Reason, still untamed!

The rising fire

Is burning down the roads and turning us

to shadows,

we’ve lost everything, we’ve lost everything

there’s nothing left except the road, the night

this shadow that instead of vanishing

grows darker in the flame.

4

What will we do if, one by one,

the rivers leave us?

God, oh God, what will we do?

The Meuse ran like a whore,

the Seine’s been taken—

If the rivers leave

what will we do?

Oh lovely, clever Marne,

why did you stay in bed?

Oh Seine, this is insanity.

Oh God!

The Loire must still be there

Still waiting for us

naked in the reeds—

right?

If it leaves us, too

what good are bread and milk

if there are any left on earth?

If it leaves, too, if it leaves, God,

Oh God, what will we do?

5

I’ve counted all of you

civilians yesterday: accountants, peasants, clerks

and workers from the factories

and bums who slept beneath the bridge of Notre Dame

and sacristans and welfare cases

all the French of France, with your clear eyes,

or from the Congo, from Algeria’s back-country from Annam

where swaying palms fill the horizon

and the French from the Antilles

French according to the rights of man,

the sons of barricades and guillotines,

the sans-culottes, the incorruptible, the free

and Czechs, Poles, Slovaks

Jews from all the ghettos of the world,

who loved the earth, its shadows and its rivers,

all of them by dying laid a seed in earth

and now are French according to their death.

6

The day is over—it is night

and day again and night again

another sleepless century

and limitless eternity

ahead of us.

A human river running, running out

Another river of insomnia

another river, faces running

through my vision

and my face

is running through their visions too.

Will this night ever end?

Oh if it were a mirror

we could break it

if it were a house

we’d burn it down

and if it were a belly

then we’d cut its child out

Soaked red!

7

Then we were leaving Paris. Oh, Jerusalem,

if I forget you ... now

you’re not a city, just an old communion wafer

bread of flesh, of blood

we’ve left behind, although we carry you

with us into captivity, humiliation

agony, the vomit and the wound.

Sweet pool of Siloam!

Oh Seine! And Paris will become another Wailing Wall,

the day Assyria,

that bloated bladder

bursts!

There are so many Jews on earth, oh Lord

They have forgotten you, no doubt

stiff-necked and stubborn people, yes,

but crying out to you. Do you remember

Aaron, strong of hand, cast out the goat

that carried off our sins? Now I am Aaron.

On my knees, I’m crying

in the language I’d forgotten but

remember in the evenings of your wrath:

Adonai Eloheinu Adonai Ehod

8

Adonai Eloheinu Adonai Ehod!

Have mercy on the land of France!

It’s beautiful the way you made it

out of nothing with your wise and loving hands

its vineyards and cathedrals

horses hard at work and clear-eyed men!

Have mercy, Lord, on France

France as I learned it out of books,

and as I see it now, heart-breaking, filthy, bleeding

and cut open to the ode’s immaculate heart—

Adonai Eloheinu Adonai Ehod!

You know when everything is calm again

on earth and in the heavens

we will have forgotten You. You know that from now on

the memory and secret of this prayer

will shame me utterly. I’ll hate you, God

for having listened. I’ll hate myself

for having prayed. You know that I have other gods

than you, hidden and faithless.

But here on the road, amid disaster, in

the chaos, there’s no other God. You are alone!

The dreadful, fiery, merciful, One!

[...]

18

Alarm bells rang

in a thousand empty houses,

grain grew wild

far from the farmer’s sight.

On empty fields

and empty schools,

and empty churches,

night fell suddenly.

The nightingale

sang anyway!

This was an ancient story

in the time when there was still a world

Blake Smith, a contributing writer at Tablet, lives in Chicago.