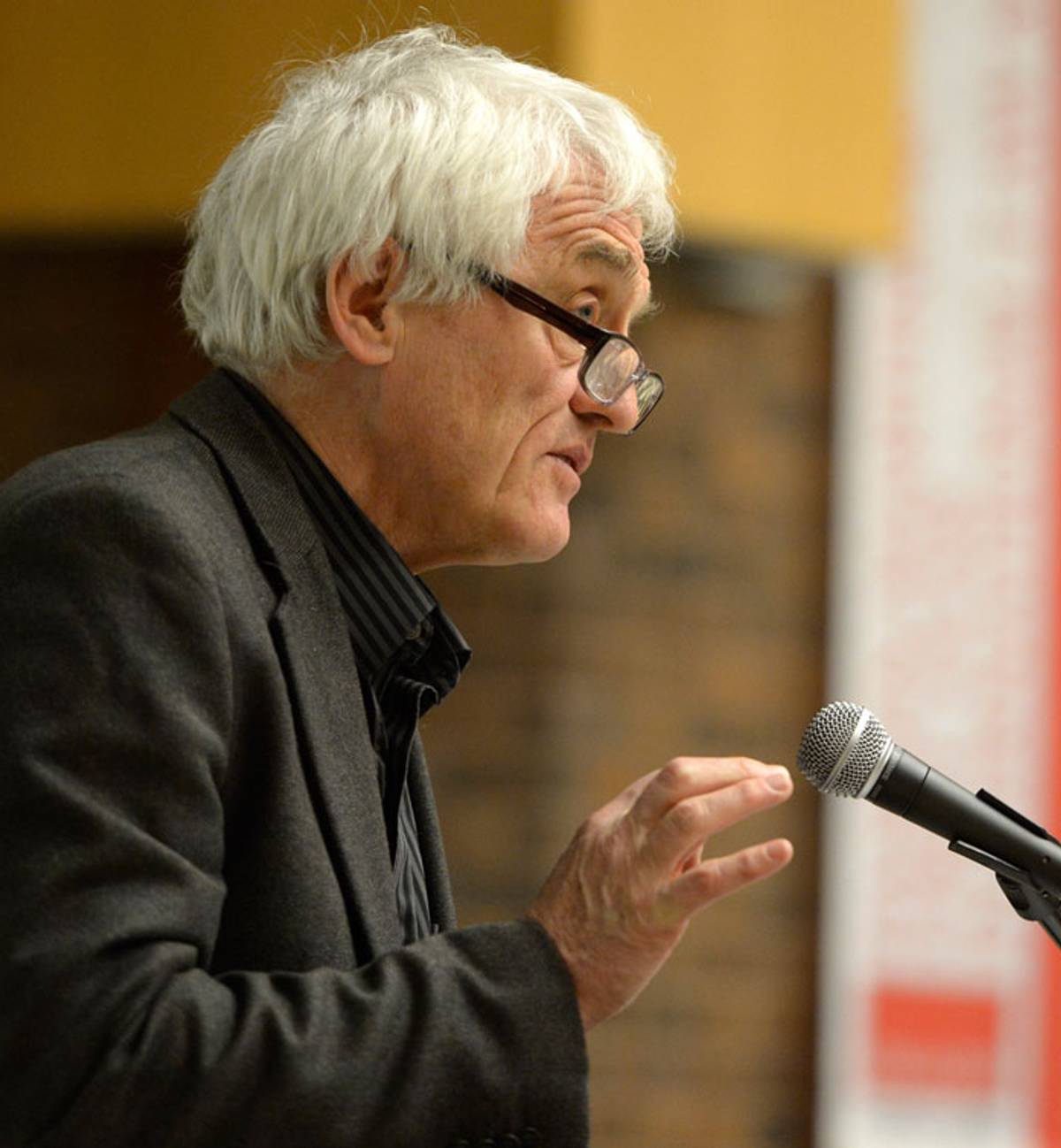

Jan Gross’ Order of Merit

The groundbreaking scholar of Polish anti-Semitism is caught up in a toxic new nationalism that seeks to edit shameful persecution of Jews out of history

1.

We Poles had our presidential race last year. In a televised debate—the most important debate of the race—the two main candidates asked each other questions. The first round of these questions, posed by candidate Andrzej Duda, did not deal with the state of the Polish economy, nor relations with Ukraine and Russia. It had to do instead with a crime committed over 70 years ago in Jedwabne, a village in northeastern Poland where Polish Catholics incinerated their Jewish neighbors. This event was uncovered decades later by Polish-American historian Jan Gross, now a professor at Princeton. Duda admonished his opponent, then-incumbent President Bronisław Komorowski, for allowing Poles to be “wrongfully accused by others for participating in the Holocaust.” He asked why the president failed to defend the good name of Poland.

The election was won by Andrzej Duda, the candidate who resolutely rejected the painful truth of Jedwabne. The new president then proclaimed a “new historical policy strategy,” which would enhance the perception of Poland in the world. That policy is already in place. And an important component of it is a campaign against Jan Gross. In January, President Duda went to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for an opinion on the question of rescinding Gross’ Polish Order of Merit. According to his spokesman, the offices of the president had been inundated with letters bearing precisely this request from outraged citizens. The president could not simply ignore—or even silence—those voices.

This came across like a grim joke, given that in the freezing days that followed thousands marched in locations all over Poland to protest the president’s new policies, and yet the voices of the protesters has gone completely unheard. We were protesting the threat to democracy suggested by the president’s refusal to swear in three legally appointed judges to the Constitutional Tribunal. We protested—and the demonstrations took place in 36 cities—in the name of freedom, against the actions of a government restricting civil liberties in a variety of ways: through new surveillance regulations, new criminal procedures, the politicization of public services and the appropriation of public media by the ruling party. We write letters, too. They go unanswered. In defense of Gross, Poland’s most prominent intellectuals produced letters of protest, and historian Timothy Snyder (Yale University) announced he would renounce his own Polish order.

Gross, whose Order is now at stake, was previously decorated twice by the Polish state.

The first time was in 1996 (before he began writing the books that would upset so many Poles). He received the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland for his books on the underground structures of the state during World War II and Polish children sent to Siberia, as well as for his personal record of opposing Soviet rule, for his participation in the protests of 1968 and his support of the independent resistance movement after his emigration.

The second time was symbolic. It occurred on July 10, 2001, the 60th anniversary of the crime in Jedwabne. Then-President Aleksander Kwaśniewski apologized to the victims in a ceremony televised worldwide. All of this was due to a relatively slim volume written by Gross entitled Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland, which had been published the year before. A book that set off an avalanche, the biggest debate in Poland since it had regained its independence in 1989.

This second Order of Merit is what the regime now wishes to revoke from Gross and to erase from public memory. And while they’re at it, they’re also revoking the medal he received for absolutely uncontroversial service to Poland, even according to the newly imposed political criteria.

2.

A few years ago in Krakow I watched as a cluster of photojournalists elbowed their way up to Gross, trying to get a good shot of him in a kippah. It was at an event centered around his book Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland After Auschwitz, which talked about the Kielce pogrom and other instances of Jewish murders immediately following the war. The event was organized by the city’s annual Jewish Festival and took place in the Kupa Synagogue, site of much cultural activity, and every man in attendance received a kippah at the entrance. The pictures of Gross wearing Jewish headgear made the front page of the papers and were shown on TV. The message was clear: Gross is a Jew, therefore a foreigner, an outsider, therefore lying. It might be worth noting here that since World War II, as a result of the Holocaust and the shifting of borders, almost all Poles have been of Polish ancestry.

Jan Gross’ ancestry is as it should be on his mother’s side, but evidently that is insufficient. Hanna Szumańska-Gross came from a landed family; after writing his book on Jedwabne, Jan even discovered that the first castellan, or official, of the Łomża territory on which the tragedy of the Jedwabne Jews occurred, was his ancestor. During World War II Hanna Szumańska-Gross worked for the underground Home Army (AK). Distributing the AK’s illegal publications, she encountered Zygmunt Gross, who was in hiding, and after the war she became his wife. When Jan Gross was rebuked for never writing about the aid provided to Jews by Poles, he explained that he himself was the fruit of such aid, but what interested him was what could have happened to make Poles who did save Jews during the Holocaust afraid to talk about it after the war.

Jan Gross has performed myriad services for Poland (as in fact did his Jewish forebears). It could be said that he played a part in the resistance since childhood: In high school he founded an illegal organization called the Seekers of Contradiction Club with Adam Michnik at the age of just 14. (Michnik was 15.) At the University of Warsaw, he was one of a group of students who organized acts of protest. After a particularly vocal rally in the courtyard of the university in March, 1968, Gross was arrested and spent five months in prison. In 1969 he and his parents left the country as a result of the anti-Semitic campaigns. Like many of those émigrés, who were essentially thrown out of Poland and whose citizenship was revoked, Gross supported the Polish resistance movement, spreading word about its activities abroad. He co-founded the fantastic émigré journal Aneks. He wrote his dissertation at Yale on the Polish underground nation. That later became his book Polish Society Under German Occupation. In the mid-1970s Irena Grudzińska-Gross and Jan Gross happened upon unique documentation of Polish citizens deported into the depths of the USSR. They published this in Polish in a book titled In 1940, Mother, They Sent Us to Siberia. In the ’80s, on the basis of documents taken primarily from the Hoover Archive, Gross wrote the book Revolution From Abroad: Soviet Conquest of Poland’s Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia.

He told me: “I wrote about the persecution of the Poles, and Jews were not part of Poland’s history. Jews were studied by scholars from other fields. Even I blindly accepted this distinction.”

Until finally he came across some documents that would forever change his writing. First, an unknown excerpt from a report by Jan Karski, courier and emissary of the Polish Underground State authorities. Karski wrote that the relationship of society more generally to the Jews was largely indifferent, often merciless, and that this issue created “something like a narrow footbridge where Germans and a large contingent of Polish society meet amicably enough.” Then he came upon the testimony of Szmul Wasersztejn from Jedwabne describing how his family, as well as an entire Jewish population, was incinerated in a barn by Polish neighbors. This gave rise to Gross’ book Neighbors, which forever altered Polish consciousness. Though of course, not the consciousness of all Poles. Jarosław Kaczyński, the founder of what is now the ruling party of Poland, Law and Justice (PiS), and the key player in Polish politics, has stated that Neighbors is anti-Polish libel and the result of Gross’ anti-Polish hysteria.

After Neighbors came Fear and Golden Harvest, co-authored by Irena Grudzińska-Gross. The release of each of these books was a major event in Poland, arousing fierce debate. Gross’ style contributes to this ferocity: It is emotional, electrifying, and it forces the reader to really grapple with the material. Golden Harvest opens with a photograph of Poles caught by the police after the war digging up gold teeth and other valuables from the terrain around the Treblinka concentration camp. The authors write, “We begin to understand … that the usual response of a Pole to Jews encountered on the Aryan side … was to unmask them rather than to offer them shelter. … This is why the photograph of Treblinka’s peasants—also, undoubtedly, ‘normal, ordinary, hardworking, religious, and possessing a whole array of virtues’ ”—in addition to evoking disgust, is so frightening: We cannot know for sure that it will not one day be pulled from our own family album.”

Alongside the publication of Gross’ books there was a surge in plays, artistic statements, and novels about Jews in Poland. I’ll give just one example showing how what Gross has written has entered into the popular realm. In a Polish novel Night of the Living Jews, the main character is a resident of an apartment block built up on the site of the Warsaw Ghetto, which was burned to the ground. Murdered Jews begin to escape from the basement of his building and rise up to his apartment. In the novel there is a Grandpa, as though taken straight out of a family photo album, who delivers a monologue to the main character and his girlfriend about how he spent the war: “We used to party, too, you know—you think you invented all this? I remember how I’d meet up with my pals and go out looking for girls, go out dancing, drinking, just go crazy, have a bite. I’d sit in town with my pockets full of gold teeth. The world was our oyster!” Interestingly the author of this book, Igor Ostachowicz, was at the time of writing it a high-up official in the previous government, that of Donald Tusk. This could undoubtedly not occur today.

3.

In September of 2015, Gross wrote a piece for Project Syndicate in which he worried about the lack of solidarity with the refugee crisis in Europe as it unfolded. He located the reasons for this lack in Polish attitudes during WWII and in their not having reckoned with their past, when “Poles killed more Jews during the war than they did Germans.”

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that this text was “historically inaccurate, pernicious, and offensive to Poland,” and Polish Prosecution opened an investigation into Gross. The basis for this was an article in the Criminal Code. “Publicly insulting the Polish Nation or Republic is punishable by imprisonment for up to 3 years.”

The foundation aptly named Good Name Redoubt—Polish Anti-Defamation League organized a petition and a letter-writing campaign to try to get Gross’ Order revoked. Examples of the foundation’s style include: “Gross is an extremely dangerous slanderer”; “Gross has crossed all the possible lines of spitting on Poland”; “Gross is a lethal threat to Poland.” Among the members of the board of this foundation is the deputy prime minister and the minister of culture, newly appointed by the right-wing regime.

In January, President Duda asked the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs for an opinion as to whether or not it would be possible to revoke Gross’ official decorations (it was at the behest of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that Gross received his Order). I do not think it will come to that, nor is the actual revocation of the Order the most important issue here. What matters is the scapegoating, the sowing of hate, and the subsequent closing of ranks in an imaginary siege. When I searched on Google for Gross and Magierowski (the head of the president’s press office, who has publicly spoken out against Gross), the result was the latest installments from his Twitter account, at the top of which was someone’s tweet on Gross: “Take away the fucker’s citizenship. Piece of shit!” It is this tone that is slowly increasing in volume in Poland. The right is becoming more and more extreme, widening the range of its enemies, speaking increasingly the language of hate. Jan Gross’ children told me that they asked their father to pull his hat down over his eyes when he was on the street in Poland, fearing for his safety.

It all gives a sense of déjà vu. In Communist times the authorities also felt they could determine what was permissible to say and publish. You could end up behind bars for three years for views expressed in a private letter sent abroad. The worst offense was publishing a critique in the columns of the press of the German Federal Republic. Anti-German resentment made many Poles think the authorities were right in this. Jan Gross’ piece about refugees, disseminated by the American Project Syndicate, was published in the German newspaper Die Welt, among other places. Now whenever anyone mentions Gross’ article in the Polish papers, on TV or in official statements, that mention always includes the ominous words Die Welt. And unfortunately, it works. In a way it’s fascinating how our right-wing government now replicates old communist habits.

It would be difficult to delude ourselves that the idea of revoking Gross’ order for a piece of journalism is a one-time freak exception. The attack on Gross is not only an attack on Gross. It is an attack on freedom of speech and an attack on the independence of scholarly work. Further installments are to be expected.

4.

Gross’ revelation of the crime in Jedwabne led to a revolution in Polish thought on Polish-Jewish relations. Poland stood at the forefront of European nations reckoning with their wartime past. Yet now a kind of counterrevolution has occurred, putting an end, as the current regime claims, to the “pedagogy of shame.” Except that this is not an invention of the new authorities. The foundations for it had already been laid. The counterrevolution has been going on in Poland for a good few years. The referral of the case against Gross to the prosecution took place under the former government (the rightwing candidate became president in August of 2015, and the rightwing government came into power in November of the same year).

Some elements of the revolution, as always happens in History, did get absorbed. The crime in Jedwabne, like the pogrom in Kielce in 1946, make appearances in the main exhibit in the newly opened Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw. The Polish Center for Holocaust Research, a prominent center of study, does great work, publishes a great journal and great books. But what is difficult and painful in Polish-Jewish history has been relegated to the margins of public debate. Now is the time to talk about how much good Poles have done for Jews—that’s what historians are doing, and the government, and state institutions, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the media.

For many Poles, the most important thing about the Holocaust is proving to the world that Poles conducted themselves in exemplary fashion during that period. This has always been our obsessive question: What will the world think of us? And the revelation of the crime at Jedwabne led to Polish-Jewish relations during the time of the Holocaust becoming an even more sensitive spot, a nerve where the Polish ego suffered damage.

It used to be that our national heroes had died in uprisings and wars. Now we have two national heroes we promote abroad: Jan Karski, who informed Western governments and President Roosevelt about Jewish extermination camps; and Irena Sendler, who saved Jewish children. It is they who are to form the binding canon of what to talk about when we talk about Polish attitudes to Jews during WWII. It was we who strove to shake the world out of its indifference to the plight of the Jews, and it was we who saved Jews, though in Poland to do so was punishable by death.

Jan Karski and Irena Sendler (and women sympathetic to her cause) were fantastic people, but their empathy with the Jewish population is not representative of the general Polish attitude during the war. Most of those who saved Jews were lone actors, working in spite of prevailing norms and afraid to talk about what they did after the war, not wanting to be ostracized by their society.

Gross’ assertion that Poles caused the deaths of more Jews than they did of Germans during the war, so difficult to accept, nonetheless strikes me as incontrovertible. The level of denunciations and murders of Jews committed during the war is staggering. For many years now I’ve been interviewing survivors, reading archives, and it is still so hard for me to fully take in the information I hear and read. In every place on the map that I happen to end up, I discover Jews murdered by their neighbors.

As a Pole, I would like for the history of Polish-Jewish relations to be like how they’re cast by the current authorities and not how they are described by Jan Gross. I would also prefer that as a Jew. Out of my extended family living in Skryhiczyn, a little village in eastern Poland, no one who stayed there during the war survived the Holocaust. In the new, improved version of history perhaps at least a child would have been spared, hidden by some neighbor. “I’m working on the world,/ revised, improved edition,” wrote our poet and Nobel Laureate Wisława Szymborska. But what befits a poet does not befit a politician.

Translated from the Polish by Jennifer Croft.

Anna Bikont, a journalist for the Gazeta Wyborcza, Poland’s main newspaper, which she helped found in 1989, is the author most recently ofThe Crime and the Silence.