Jim Dine’s Bathrobe

The painter reflects on sunken ships, his family’s Jewish history and those goddamn hearts

“It’s a problem I have, I guess. I can’t maintain my cool. I’m always being sloppy … excessive.” —Jim Dine

I once had the opportunity to introduce the artist Jim Dine at a poetry reading at the Dia Art Foundation while I was working there briefly around 2013 as director of publications. I must have lost my cool, because I said something so unlike me that I still hear it echoing in my ears and it still causes me an ache of embarrassment and humiliation every time I rehear it. I stood at the podium before the silent, serious room and hit exactly the wrong note: “Jim Dine is IN THE HOUSE.” Ugh. I came across like the host of a cheesy late night talk show, yo.

On that evening, Dine was appearing in the so-called “house” as a poet—poetry has always been a significant aspect of his work that is not generally recognized by the art or poetry establishments. Suffice to say, his reputation is more than secure as a visual artist. If you’ve ever picked up an academic art history textbook, you will see that back in the late ’50s and early ’60s Dine was one of the innovators of Happenings and a pioneer of the pop art movement. He has been working steadily ever since. Some would consider him a living legend.

I was in Chelsea recently for a meeting with Dine, who was installing his new show at Templon. I pulled the fancy frosted glass door and immediately discovered a legend in the flesh, who was in the midst of a chaotic situation, instructing about five big strong men, who may or may not have been wearing yellow protective hard helmets (I can hear the Jewish mother in me cautioning them to “always wear your helmets”), working with a giant industrial crane to lower a massive bronze sculpture into place—one of the “Three Ships” that will be installed at Templon through July 28.

Jim was pointing to the exact location on the floor where this hulking metaphorical ship was to be set down, and the art handlers were all being polite and accommodating. My impression was that everyone loved Jim and was committed to helping him pin down the exact vantage point in the room that would give viewers the best chance to discover the subtle nuances of the work in the round.

When Jim saw me, he backed away from the manly work, and switched gears to his more intellectual demeanor, expressing how long he had lived with the works in his studio. The metaphorical “ships” looked a little like ruins left behind on parched land after a catastrophic drought—or what is now called an extreme weather event. Or like the corroded, barnacle-coated wreckage of a sunken tanker dredged up after a century in the dark salt water, seated on the sandy ocean floor—they looked weathered, or in the T.S. Eliot sense: wasted! They conveyed a feeling of obsolescence, like a city in Japan after a nuclear bomb drop. My inner Philip K. Dick was seeing them as sci-fi fossils from a distant past when mankind still hammered, sawed, raked, drilled, trimmed, clipped, and screwed.

These three gigantic shiplike creations had been “dined”—made to be mighty and tower in the room.

“They just released new images of the Titanic.” I ventured. “These look a little like those.”

Jim looked surprised that his ships had conjured up such a feeling of doom, though when I mentioned that I saw a little of Samuel Beckett in their end-of-times absurdist theatricality he pleasantly agreed. “These go further than any of your previous Tool works,” I said, “they have accumulated exponentially, and now look like the displacement of the entire inventory of a hardware store.”

Jim chuckled. He could tell that I was leaning into them, and that they had triggered my imagination. Soon, more specific objects began to appear from the camouflage-assemblage—including actual power tools like a Black & Decker-type power drill hiding in plain sight, and a hatchet, hammer, saw, and full variety of gardening equipment, including clippers, a rake, a hoe, a pitchfork, a shovel, and a muddied broom. It was as if that hardware store had been dragged by rising flood waters and carried right into the gallery, before magically turning into bronze.

Jim seemed both pleased by their dramatic presence, but perhaps a little sad that I was perceiving them as being quite so dystopic. “They came together organically,” he said quietly.

“Like the toolshed in every backyard across America,” I offered, while delighting at Jim’s dadaist sensibility. These were melancholy monuments, three dinosaurs, hallucinatory quixotic windmills—Giants!

Jim turned away and I followed his lead down a set of stairs to another side of Dine—his painterly side. In an intimate gallery space, there was a series of medium-size oil paintings that were extremely saturated, impasto-ed, gestural and brushy—another feast for the eyes. Each an exuberant self-portrait.

On another wall hung 12 smaller graphite drawings that were lifelike and tempered by a process of careful Cézanne-like obsessive observation—i.e., capturing one’s likeness in the mirror.

I quickly scanned the entire gallery of cartoony, somewhat exaggerated Jim Dine faces, turned to him and said the first thing that came to mind: “Why the big ears?”

“Cause I have big ears,” Jim said, looking right at me, as if presenting his face for viewing.

Jim then explained how COVID had kept him indoors, and how productive that year had been in Paris where he lives in the 14th arrondissement.

“Do you consider yourself an expat?” I asked, thinking of the painter Joan Mitchell who was famous for her need (back in the ’60s) to flee the New York art “scene” and retreat to a quiet studio outside of Paris, where she could paint in peace, hang out with the dogs, drink nonstop, kill the occasional pit viper (according to a story she once told), and enjoy drop-ins by gossipy poets like John Ashbery.

“I’ve been going back and forth to Paris and other parts of Europe for 50 years. And I spend a lot of time working in Germany. But I’m in America a lot, because I keep a farm on the Pacific Northwest.” He paused. “I am happier in Paris. Paris just looks better.” And he laughed—a contagious laugh.

I was reminded of a filmed interview I’d found online of Dine back in the ’60s when he was a brash 30-something, bad boy art star holding his own with Warhol and Lichtenstein, and the rest of the Leo Castelli Corp. In the film, he eviscerates the trendy New York art scene. “I found that people wanted to see me more than they wanted to see my paintings,” says Dine in the film. Then with a grin. “They all wanted to see how your wife dresses.”

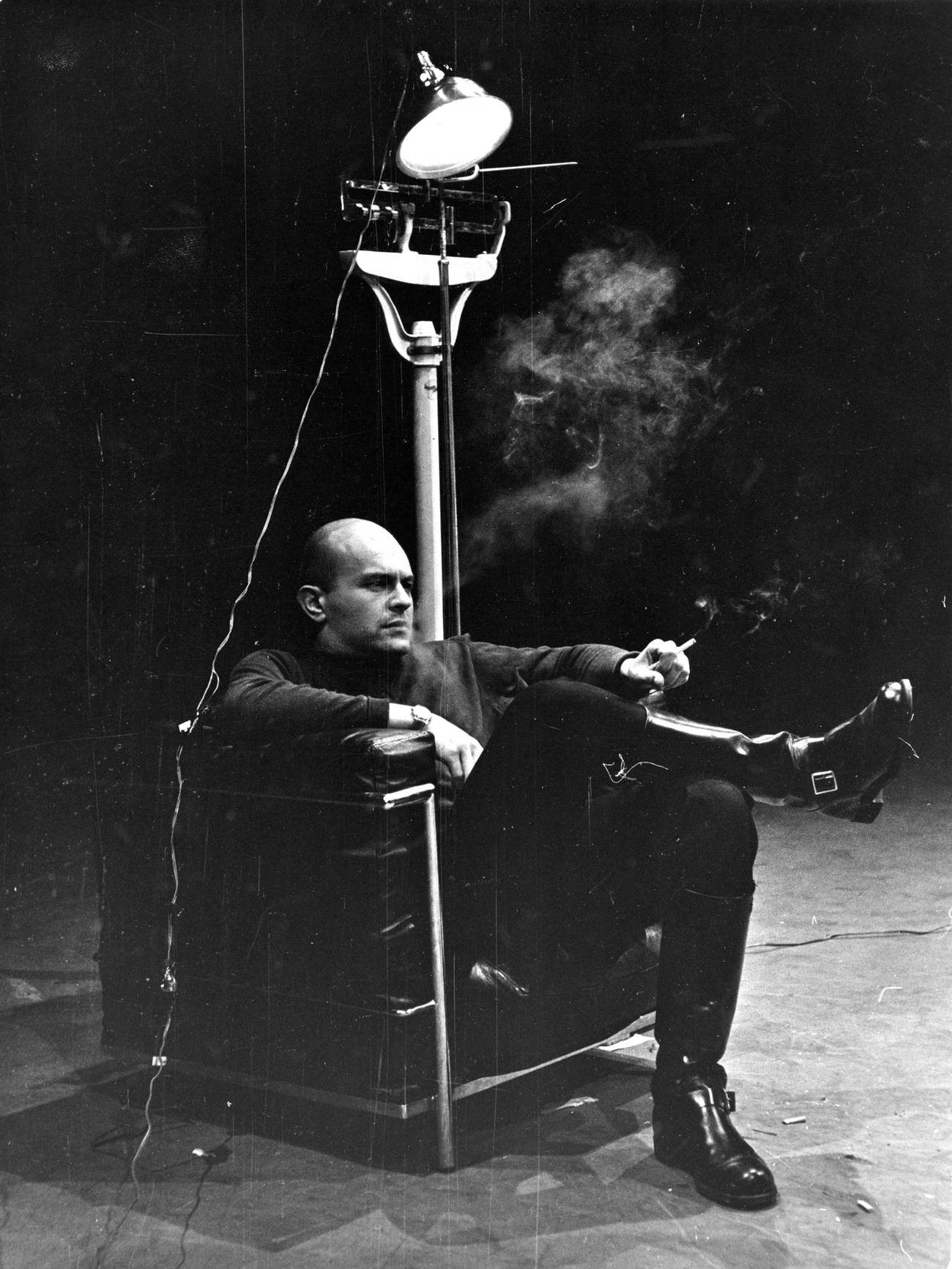

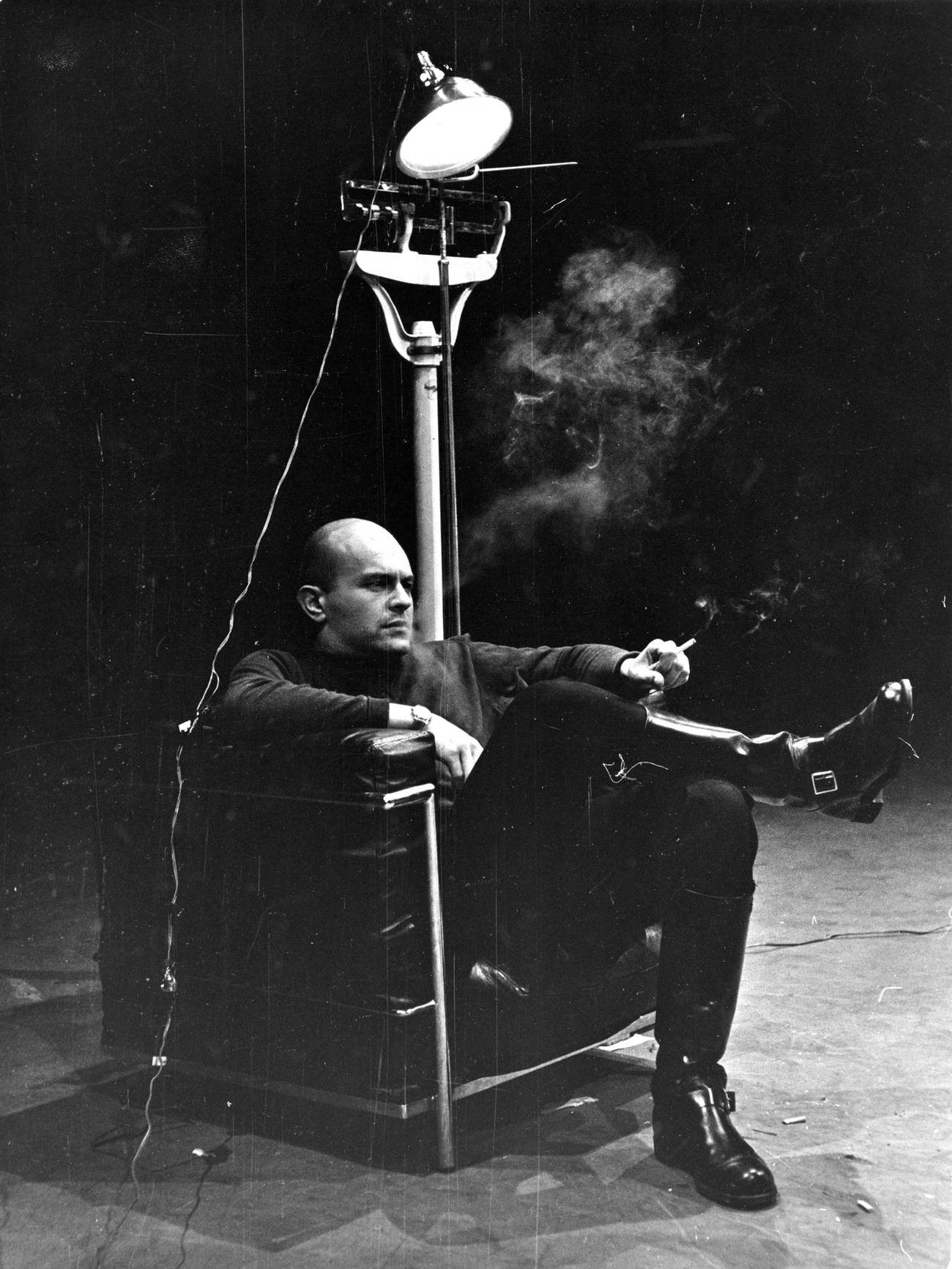

I compared the youthful Jim Dine standing before me to the young man in the black-and-white documentary film. What did it reveal? In one scene we watch him from the passenger seat of a Volkswagen bus (a Beat mobile) driving into the city, attempting unsuccessfully to tune in on a radio station. In another scene he is dressed in a handsome thick turtleneck sweater sitting in his living room. His eyes hide from the camera. He tries to come off like a family man, but it’s hard not to feel his brooding angst and to suspect, from his devilish grin, that he is easily distracted from domesticity.

In the film he says: “I live what I consider a very middle-class life, with three children, and a wife. And feel it is very necessary to maintain it at all times.” He then contrasts this to his studio life, where he explains he is free to “experience certain kinds of madness.”

And he pronounces that he intends to spend his life painting about himself and going on a “very long voyage.”

Here we were in 2023 and Dine is still on this voyage, still boiling over with boundless creativity—still making art with the muscle and bravado of a 20-year-old. The word voyage naturally reminded me of the “Three Ships” upstairs, which had just made their maiden “voyage” to NYC after being cast in Baker City, Oregon. Then I thought about Jim’s background, which like my own, involved a classic ancestral crossing of the Atlantic and arrival in America. I asked Jim if he didn’t mind talking about his family history.

“I was raised Jewish!” He laughed. “I was born in Cincinnati in 1935, which was one of four or five German Jewish towns in America then—others being Baltimore, San Francisco, St. Louis, and of course New York.”

“I have three grandparents that were born in Europe. And one who was actually born in Richmond, Virginia—my grandma. My grandfather came to America with his two brothers when he was 18. They left their parents there at their mill in a country town in Poland. The three of them were big country boys, who had been indentured by a cousin called Hunchback Cohen … Humpy Cohen, they called him.” We both laughed. “He was bent way over—but he was a shark! He got them all there and gave them jobs, for a fee. My grandpa, who was just a teenager, went to work at the Baldwin piano company. And one day he caught his finger—this finger (Jim was now pointing a finger in my face)—in the lathe!”

I studied Jim’s finger which had an odd stumpy, somewhat deformed look to it.

“And he went to the foreman and said, I gotta go home I’m bleedn’. And the foreman said OK, so he went home, and bandaged it as best as he could. And when he arrived at work the next day, the foreman came up to him and said, sorry you’re out.

“It was before the days of workmans’ comp or sick days.”

“And after that incident, Grandpa’s finger was ground down, so there was hardly a nail on it. But whatever was there right at the end of his finger looked like a kernel of corn.”

Jim was now getting very detailed, and as he spoke, I began to realize that the flood of memories was indeed the psychological force that propelled his art. It was this internal dialogue with memory and the triggered emotions that continued to put him at odds with the detached cool pop sensibility, where mining one’s psyche was often looked down on as being self-indulgent and overly poetic. The story he continues to tell himself makes him the perpetual outsider, the rogue, despite the fact that he has worked his way into virtually every major museum collection in the world.

Dine was still going on about the traumatic finger memory: “And he used the finger to speak Yiddish to us while tickling us at the same time. It was this huge finger, and he was a bit of a bully, and I loved the guy, but he drove me crazy. And he had a very thick accent. And he and my grandma spoke Yiddish. I still use Yiddish now and then—it’s my patois. Mostly with my kids. Yiddish is our secret language.”

Jim Dine: My grandpa married my grandma (who was 16 at the time), and they headed south to a small town in Georgia where they opened a dry-goods store. They sold nails and strings, and pots and pans, dust pans and brooms, you name it—everything imaginable.

My mother’s grandfather was also a character—he was a tinkerer, and he had a horse and buggy, and he drove all over the South circumcising little boys and kosher-ing chickens.

Jeremy Sigler: He was a mohel?

JD: No! He had no certificate—I can tell you that!

JS: So I guess he would just improvise.

JD: When they died, they were buried in the Black cemetery in Albany, Georgia. They wouldn’t let Jews be buried in the white cemetery.

JS: It sounds like your grandparents must have experienced a lot of racism, which is also called “antisemitism.”

JD: Are you kidding? That’s why they left the South. I asked Grandma why we went to Cincinnati and she said, the Klu-Klux-ers. Just like that.

When they moved to Cincinnati, Grandpa founded a little synagogue with like six other Polish Jews in the neighborhood, and he really loved it. But when my mother grew to be a teenager she begged him to stop going to the Temple. She was snobbish and really wanted to be a gentile. They eventually joined a Reform synagogue, but it was a personal tragedy for my grandpa—he lost the language and rituals, and found himself in this Episcopal synagogue where services were conducted entirely in English.

JS: Inauthentic.

JD: Yeah. The place looked and sounded like a church! So I was born into the Reform movement. And just about everybody I knew went to this same temple. It was a strong part of my family, but my mother ignored it. The Seder was always held at somebody else’s house, not ours. We did go to a religious school, but it wasn’t Hebrew school. We went to something called Sunday school!

Jim was now deeply immersed in the past, which is exactly where I wanted him (and where my editors at Tablet wanted him). “I hated Sunday school,” he said with a bit of rage in his eyes. “I hated all school. The idea that I had to go to school for even one more day was ridiculous.”

“Why did you resent school so much?” I asked.

“I was dyslexic.”

“Oh.”

“But I was artistic. By age 2 I was constantly drawing. It scared the shit out of everybody.”

“Did they approve of you growing up to become an artist?”

“My mother was very proud of my drawing ability.”

“Your talent.” I smiled (the cliche of the Jewish mother had again come to mind).

“And she was also proud of my verbal skills. And that I loved to sing and dance and perform. Had I not been a painter I would have aspired to be an actor.”

“A triple threat.”

“So anyway that’s my Judaism.” Jim said, chuckling a bit. “I’m pretty embarrassed by it all.”

“Can we talk about your history becoming an artist and arriving to New York.”

“When I was 12, my mother died and we were very close. And my father remarried almost immediately—a horrible woman—a monster. And she hated me and my little brother (who is five years younger than me). And finally my father said, I think it would be better if you left. I was 13, and I jumped with glee, knowing I’d finally get out of their fairy tale hellhole.

“I went to live with my grandma and grandpa and entered high school—that is, when I went,” he said snickering as if he were still a bit of a wayward adolescent. “But I was a horrible student, and I actually cheated my way through school. The girls I went to school with were so kind to me. They would hold their test papers up allowing me to peek over their shoulders and see the answers. They were such sweethearts. But I had behavior problems, and teenage hormones.

“My grandpa then became very ill with heart disease, and I took over his car, and the first thing I did was register for adult art classes at the Art Academy, which was hooked up to the Cincinnati Art Museum. I was free at last! It was wonderful! I registered for all these classes like French (I wanted to speak French because of Matisse), and I registered for History of the Ancient World, and spent a good amount of time literally drawing from antiquity. My mother had always taken me to the museum so that I could draw their plaster replicas of Greek sculptures like the Venus de Milo.”

“So now I see where your subjects come from. They truly are autobiographical.”

“Sure. I’ve done so many Venus de Milo’s.”

“There’s a giant one on 53rd Street right? It’s about a block from MoMA. I wonder how many people walk past that thing every day? It has to be the best real estate for a public sculpture in all of New York City!”

“Yes. It was a very big public commission. But anyway, one day a guy I knew came up to me and said, what are you still doing in Cincinnati? You’ve gotta come up with us. We’re having the best time at State University of Athens, Ohio (not Ohio State). The school of fine art there is sensational, he said. And so we drove up in my car (I had just inherited it because my grandpa had passed away). And I walked into the art school and introduced myself to the professors and showed them my portfolio, which was just a bunch of drawings I had tucked under my arm, and they let me in immediately! And I had all of these wonderful professors who taught me so many techniques. But I had the sense that they really truly believed in me.”

“—which must have given you a lot of confidence.”

“I wasn’t just any other student, you know? I was really turned on. And I would stay there working in the art building like 24/7 painting, print making, drawing, sculpting… you name it. But I was also going over to the library where I found these bound copies of ARTnews going back year by year. So I started to steal them. I used them like a bible. I read and reread every review by Frank O’Hara, and John Ashbery. I read about Elaine de Kooning and Grace Hartigan. But my main interest was always in Kline and de Kooning. I thought that was the only place to go after Picasso and Matisse.”

I turned to face the collection of graphite drawings, hoping to draw Jim back into the present, to further understand his working methods. “And when you draw you really erase a lot, don’t you. I can see that the paper gets really rough and worn down and even torn in places.”

“Yes over time, after so much drawing and erasing, the paper gets very fragile. And so I often have to patch it from the back. I often think I’ve ruined one—but then I come back and I’m compelled to go further with it. In fact, I’d like to continue on a few of these.” He smiled.

“And I use my fingers a lot.” Jim showed me his left hand again, and a rather deformed stubby middle finger. “This one, it was injured about six years ago when the disc on the grinder I was using flew off. It seared the bone and fucked up my fingernail. And now the finger is always a little numb. But I can use it like a mahl stick, the same way Matisse did to steady his hand.”

“I’m reminded of the story you told before about your uncle’s horrific finger injury.”

“Yup. When I showed my finger to all my kids they immediately said, Morris Cohen.”

Jim and I finally sat down and sunk into this sofa in a private room, I turned to him, and in a moment of perhaps too much honesty, I confessed how much I “struggled” with his art. I chose that word carefully. I also told him that I had mentioned to a colleague that I was working on a piece for Tablet on Jim Dine, who responded with, “Oh I haven’t really thought about his work in a long time.”

Jim looked at me with growing curiosity.

“I call it the Jim Dine paradox—you are a forgotten artist that no one can forget. And even weirder, nobody can remember why they forgot you.

It’s always a little hard to tell if you were ahead of or behind the pack. Or maybe just off in the corner doing your own thing. Like those very banal tie paintings from the late ’50s—they are actually pre-pop.”

“If anything more like very early Red Grooms, or Larry Rivers, or even Joe Brainard.”

Why did I have an attraction but simultaneously a repulsion to Dine’s imagery? Had I not looked hard enough? What was I not seeing or “reading” in the pages of his very honest coming-of-age story—in his Palettes (once compared to the elegant swerving Ohio River); in his bathroom sinks and medicine cabinets fixed to canvases in the same manner as Rauschenberg and Johns (works that certainly foreshadow Damien Hirst’s very clever Pharmacies); in his Tools (often appearing like eroticized nude women, allowing you to stare at the gaps between their legs; in his vulgar men’s Bathrobes (portraits of an invisible man in the liminal space between dress and undress); in his replicas of the ancient beheaded Venus de Milo (a reference, I know, understood to be leading straight back to his first fan, his mom); in his creepy Pinocchios (a doll he dragged along with him for much of his adult life); and perhaps mostly in his big pendant Hearts! Those goddamn hearts!

Why did I have an attraction but simultaneously a repulsion to Dine’s imagery? Had I not looked hard enough?

The painter Alex Katz (who is about Jim’s age), I told my wife, is rediscovered by every generation who falls in love with him; when the next generation discovers Dine, they become slightly offended by him all over again. Is it his sloppy excessiveness? His psychoanalytic probing? His grandiosity? His mojo? His Hemingway-esque hubris? His Energizer bunny productivity? His wide-eyed ambition that inevitably leads to self-destruction and catharsis?

I tried harder to explain my mixed feelings. “I’ve never actually dismissed your work, but I haven’t ever quite come to terms with it.”

Jim’s face looked bemused. He is 88, and hard at hearing, has a very bald head, and a little bit of saggy flesh around his neck, but could pass for 50. Let’s put it this way, he looks like he can still get it up, with or without Viagra.

“Can we talk about the bathrobes? I’ve never worn one. Nor have I sat back in a barber chair and had my face shaven. Nor have I ever used one of those black pocket combs. No offense, but when I see a bathrobe right now in the post-#MeToo moment we’re all in, I get this cringy feeling.”

“Why is that?”

“First I think of Charlie Rose. He was #MeToo’d if you recall after a woman on his staff said that he invited her to his estate in Bellport, and after getting water on his pants, reappeared in a white bathrobe, which he left open in front of her and other employees. According to the woman, he had nothing on underneath.

“I see the men’s bathrobe as a signifier or something. It even appears in the Harvey Weinstein case: According to a similar story by Lauren Hutton, she was invited to Weinstein’s office in Tribeca to read a script, and Harvey appeared in a dirty white bathrobe.” In People, Hutton said, “The bathrobe was enough for me.”

But is Dine’s bathrobe enough for me? Yes, and no. Maybe I want the robes to be even creepier, the way Hugh Heffner creeped us all out with his velvet and satin monogramed smoking jacket, which became a major component of the Playboy lifestyle. In the ’70s, Harry Nilsson appeared on the album cover of his grammy winning Nilsson Schmilsson in a yucky brown terry cloth bathrobe.

Dine rather innocently remarked “I found it while leafing through the pages of The New York Times magazine section one day—it was this enigmatic, figureless bathrobe. The man’s body had been airbrushed out.”

For some reason Dine felt that his own body was missing from the robe. He was either consciously or subconsciously looking into his dreams at an archetype of the father or discovered some dimension of his repressed inner masculinity. Or just going with the flow, expressing one of many popular department store products of the day. I told Jim that I probably would have entirely rejected his work years ago due mainly to his cringe-worthy bathrobes and ridiculously sentimental hearts had I not encountered one very messy brushy heart with a small cyclops eye directly in its center, slightly cropped, and printed on the New Directions paperback cover of the “one-eyed poet” Robert Creeley’s collection titled So There: Poems 1976-1983.”

Jim looked a little confused—my guess is that he was now thinking he’d been ambushed: “Why did this guy come all this way up to Chelsea to trash my work and cancel me.”

“What is weird,” I said, hoping not to dig my grave any deeper, “is that while I never liked your work, I refused to disregard it. I can still feel it working in the wood shop of my subconscious, grinding, sanding, always cutting against the grain of my brain. I love its potential to be built into meaning, in spite of my distaste for it.”

This didn’t seem to make matters worse. While Dine still looked a bit surprised by my honesty, he was certainly not angry.

“‘Against the grain of my brain.’ That’s a good line,” he said.

“Thanks.” I said, and I got back on my train of thought: “Here’s my rationale,” I said, “If Creeley liked you enough to put you on the cover of his book, then I like you too.”

And with this comment Dine’s face, which was frozen in hard concentration (as he was now trying to figure me out, kind of as a fellow poet, and fellow weirdo), dramatically seemed to pop open like one of those combination locks that you keep spinning clockwise and counterclockwise stopping at various numbers you can hardly remember.

Jim’s eyes came to life and a big smile formed revealing a beautiful set of amazing teeth for any man his age, and a lovely smile. Those hearts go back centuries, and they spike in popularity every year on Valentine’s Day and even made it onto Glazer’s very famous “I [heart symbol] New York.” Go back to the fourth grade and try to remember folding that red piece of construction paper in half, cutting that wonderful curve with those little lefty scissors (did I tell you Jim and I are both lefties) down the diagonal line arriving at a single point. Unfold the paper, and there it was!—that perfectly symmetrical heart. Then out would come the Elmer’s glue and the crayons, and you’d write “I love you Mommy.”

“You know Jim,” I said, trying to keep myself afloat, “I do want to know what drove you to embrace those menacing hearts and to keep drawing painting, printing, and sculpting them repeatedly, knowing how frustrating they were and still are, with their undeniable sentimentality. You once said you painted a shoe and wrote the word shoe under it just to make a truly ‘dumb painting.’ Well, in my opinion, the heart is like 10 times dumber than a shoe. And like a hundred times dumber than a men’s bathrobe!”

I think Jim was beginning to wonder if he was wasting his time with a guy pretending to be a journalist, and he finally cut me off, and really busted out a statement: “I left myself open to be dismissed by so-called ‘serious people.’” he said. “But I was so happy with the show after I saw those paintings up on the wall. I knew I was finally at the peak of my powers, and that I couldn’t do better. And then I thought, maybe the next time I should make like 6 HUGE hearts! STICK IT UP YOUR ASS! Ya know?”

Just then an old man who looked like he could have been a painter from Jim’s generation walked in, who also must have been getting a sneak peek at the show prior to its official opening. He came right up to us, as if to shake Jim’s hand. But rather than interrupt us with words, he balled his hand up into a fist and lightly tapped it to his chest a few times, as if to say “Your work always has soul. Thank you for staying true to yourself!” (That’s the way I read his gesture anyway.)

I too admire Jim’s audacity and bravery and autonomy. He had claimed the heart symbol the same way Warhol claimed the Campbell soup can and Brillo box, and same way Yves Klein claimed ultramarine blue. It now made sense: It was Jim Dine’s valentine to the world—an act of unadulterated shameless kitsch. Kinehora!

Jim, of course, knew the word, and was enjoying my enthusiasm, but we were both beginning to fade. “Do you have any other questions,” he asked. ”I’m afraid I’m gonna have to catch a flight back to Paris in a few hours.”

“Yes, one more,” I said. “Do people realize how central you were to the Happenings and nouveau réalisme (which was considered mainly a movement based in France)? Do they realize that you were there at the beginning, with Grooms, Kaprow, Oldenburg, Whitman. And do they realize that you were also there at the very start of the Judson Church dance scene? Have they gone back in the archives and seen all those black-and-white photographs of you more or less inventing the genre of neo-dada performance art?”

“No. Not really.”

“I think it’s because the works were so ephemeral and the documentation has hardly been published or exhibited. You once said, ‘I used exposure of myself as a medium. I knew people wouldn’t like it, that they’d say they were bored, when they meant they were nervous … they said things like, ‘we don’t want to see his problems.’ And you also admitted to the ‘difficulty in exposing yourself’ and the drive to make it ‘difficult for the audience’ as well by ‘asking them to relate to you, rather than you relating to them.’”

In the Happenings that began around 1958 artists basically attacked the gallery “environment” (as Kaprow called it) with balls of twine, coarse burlap, crumpled newspaper, chicken wire, buckets of paint, plastic wrap, cardboard, cheap clip lights, aluminum foil, clown white face paint, wooden sticks, ladders, clothespins, underwear, bandages, bed sheets, folding chairs and utter trash. But Dine was the one who brought in the proverbial “couch”—or the experience of being on the couch in your psychoanalyst’s Upper West Side apartment office. I then asked Jim what he remembered most from the Happening:

“It was something called the New York Theater Rally,” he said, “In which Rauschenberg, Carolee Schneemann, Bob Morris participated. Along with the Judson dancers, like Yvonne Rainer, Simone Forti … and EVERYONE hated what I did. Only Carolee Schneemann got it. She said that I was the only one who had ever dealt with their unconscious.”

“What did you do?”

“It was me just sitting in a chair smoking a cigarette. And people around me doing specific jobs over and over. And there was this prerecorded audio track of me reading my dreams out loud. And it continued for about a half hour.”

“Like a poetry reading.”

“And it pissed so many people off. Because people wanted action. But for me this was the action. Critics and historians like Annette Michelson or Rosalind Krauss have said ‘I didn’t want to hear his libido.’ Or something like that—like fuck off.”

But I also remember another Happening called “The Smiling Workman.” I came out on stage, made some strange noises. My face was painted red, my head was painted red, I had a big black mouth. And there was a big canvas. And I wrote on it in a frantic way: ‘I love what I’m doing.’ And then, I took the paint that I was painting with and drank it.”

I gasped.

“And then I poured it over my head.”

“Then what?” I asked, feeling a bit like a little boy being told a bedtime story by a grandpa with a deformed stubby finger.

“Then I dove through the canvas!”

Just as Jim’s story ended my cellphone lit up. There was an incoming text message from my daughter—a heart next to a yellow round face with gushing tears. It was like a blast of pure uncut dopamine. I quickly affixed a smaller heart to her message, and immediately pressed send.

Jeremy Sigler’s latest book of poetry, Goodbye Letter, was published by Hunters Point Press.