Making the Survivor

My father made the heart-wrenching decision to leave his family behind and escape the train to Terezin. Decades later, making a film about the choices of the Holocaust brings catharsis in unexpected ways.

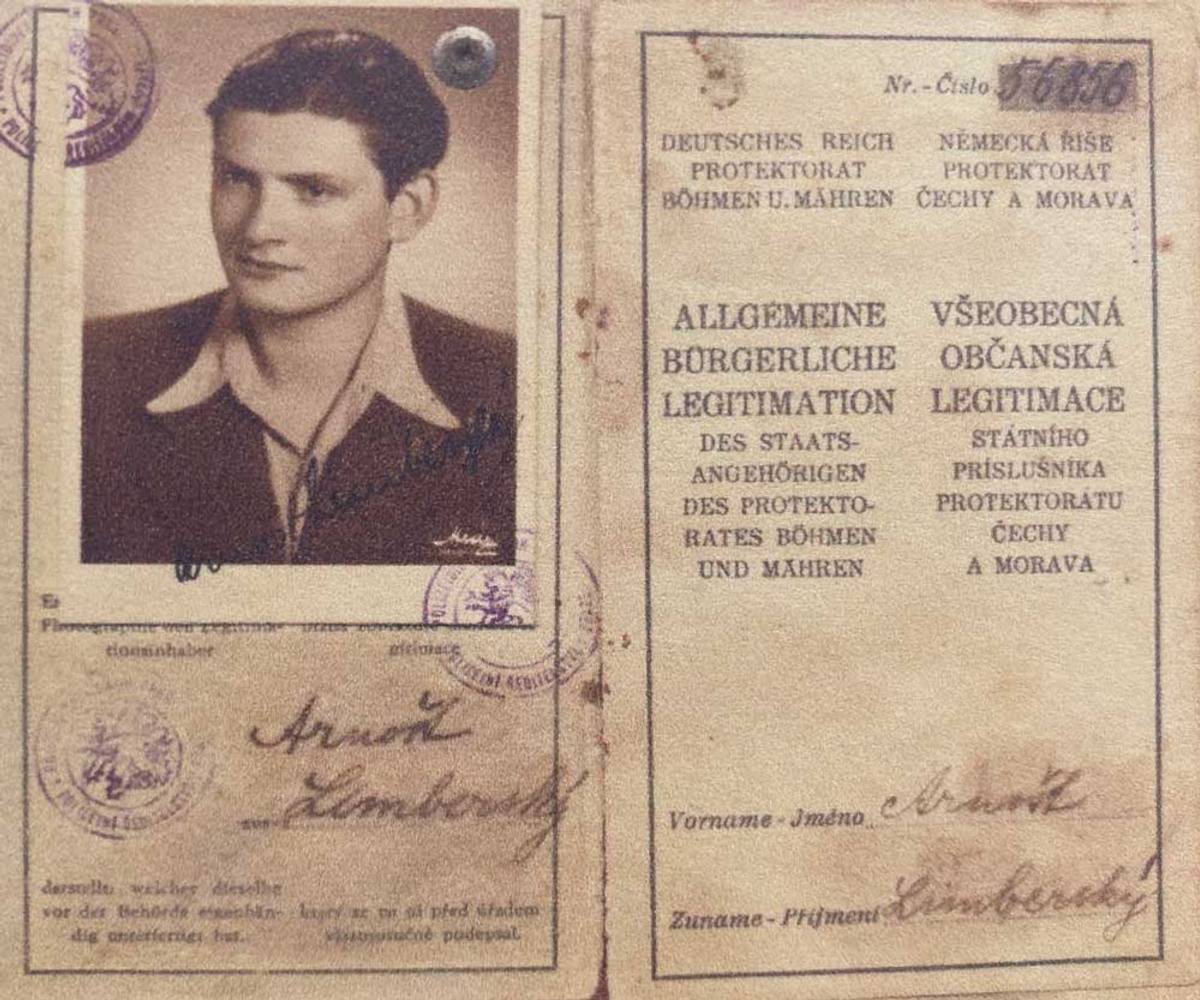

“Where are you going?” the suspicious cop asks. Slovak, he thinks to himself.“ To visit my sainted mother in Brno. She’s complaining again,” he answers. The cop chuckles, “Good man,” and hands him back his identity card. He’s taking the Prague train and traveling under an assumed identity, Arnošt Limbersky. His photograph belies the truth of his heritage. He speaks perfect Czech and perfect German, not some flat, southern dialect but Hochdeutsch. He gives the illusion of someone who is safe.

Back In Prague, Arnošt is a supervisor at the Bata shoe factory in the German language school, created because the Reich wants all Czech workers to learn German. That’s his job and his cover in the resistance and now that he’s forged his own papers, he’s forging for others. He saves a few Jews this way—maybe 10—but not enough. Never enough.

He wasn’t lying to the policeman. He is going to visit his mother in Brno. He arrives on Huteruv Rybnik 4, where he lived since he was 2. The building shares a courtyard with an old synagogue, but the synagogue has been closed for more than a year. His sister Judita opens the door, and he enters quickly. He shouldn’t be here. In the relative anonymity of Prague, he’s safer. Here, everyone knows him. At 18, Judita has her mother’s beauty unsullied by time. Hazel-eyed and tall, she opens the door quickly and lets him in. They embrace and his mother, Paula, comes out of her bedroom in a black dress. At 45, she has the aristocratic bearing of a well-bred, bourgeois Russian lady, which is exactly who she is. They embrace and she cries a little. She talks about missing her husband, who died in 1938 after succumbing to lung cancer and an 80-Turkish-cigarette a day habit. She prepares tea and serves cakes on fine china. Arnošt knows he has little time. His mother and sister have been called for transport to Terezin.

Judita knows her older brother well, having spent a lifetime idolizing him, and she can tell he has something on his mind. Her mother will just keep chattering if she lets her, so she interrupts and says, “So, why are you here?” The impoliteness of that moment stops everyone, but Arnošt draws a quick breath and dives in. “You must leave with me tonight,” he says. “I’ve arranged identity papers for both of you and we can get on the 6 o’clock train back to Prague. Everything is set.”

Hours later, Arnošt walks out of the apartment and exits the building alone. He walks quickly to the station so as not to miss the train. He stays in the shadows.

My name is Matti Leshem, and I am a filmmaker. After a journey of five years, my newest movie, The Survivor, directed by Barry Levinson and starring Ben Foster, has just debuted on HBO. While the story of any independent film being completed is a triumph, the backstory of this movie is deeply personal, reaching to the very core of what it means to be not only a survivor, but the child of a survivor.

I am that child because the story about Arnošt and his family are not the plot of the film. Rather, that is my father’s story, and he only told it to me once. In my 20s, after years of asking, my father agreed to a formal interview so I could get all his stories on tape. I think he only said yes because he had suffered a second debilitating stroke, which left him searching for words and scared him more than the Nazis ever did. He had relied on his mastery of languages for his entire life. Perhaps it was a talent he possessed as a Mitteleuropa Jew, and a polyglot. A first-year medical student, he could quote Rilke’s “Der Panther,” in perfect German while attempting to seduce a beautiful girl, and then turn to his friend and drop a vulgarity so off-color that it could only be spoken in Yiddish (to ensure the girl doesn‘t understand)—all the while ordering coffee in colloquial Czech and arguing with his hotheaded Zionist friends in Hebrew. This was before the war, of course.

In his late 70s, my father still spoke nine languages, but his fluency was betrayed by the lapses of one whose brain has been scrambled by several strokes. Ultimately, this gift of languages helped him discover his true métier, which was to be a diplomat for the fledgling country of Israel, where he emigrated after the war.

The loss of his speech was a slow death, so he agreed to talk to me. The interview was strained. We were both playing parts as we negotiated our way through his story. Sitting in his small office, vestiges of a brilliant career hanging on the wall: signed photographs of Ben-Gurion, Golda Meir, and a framed medal from the Czech government for fighting the Nazis. I covered my nervousness by playing the part of a journalist, asking questions that I already knew the answer to and wanted to record, all the while desperately looking for some underlying emotional clues. He wasn’t giving those up. Instead, he cast himself in the role of a historian. If you listen to the interview (in the permanent archive of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in D.C.) you can hear an odd sounding, if brilliant, lecture about history and the state of the Jews in Prague and Brno. His legendary wit and razor-sharp mind are seemingly diminished by the speech impediment, but it and he, are all there.

Except, of course, for the part that happened between the tape changes. As I put in tape 2 but before I pressed “record” he recounted the story of when he took the train to see his mother and his sister in March of 1942, and how he had no choice but to leave them.

That was a pivotal moment in his life. But the truth is I don’t know much more than the basic facts. He didn’t tell me any more details other than that he tried to convince them both to come with him, but his mother refused to leave her home and his sister refused to leave her mother. And so, that moment when he realizes he lost and that he must leave or risk being captured himself is the pivotal moment in his life, and I’ve been struggling to understand it for 25 years. How, at the age of 22, did he walk out, knowing that his mother and sister were doomed? And they were. The next day, they went to the train station and were transferred to Terezin. Judita died there of typhus in March of 1943. After watching her daughter die, Paula was transferred to Auschwitz-Birkenau in December of 1944, and the day after her arrival she was gassed and cremated.

Growing up with a father who had to turn his back on his mother and sister and never spoke about it was hard. It led me to search out the stories of other people who had to make those difficult choices. So, when I read the script for The Survivor I felt as though I was already on a collision course with the film. I met with the writer, a young Australian named Justine Juel Gilmer. She was an amateur boxer and a professional writer who felt connected to the Holocaust despite not being Jewish because her grandmother had fought in the resistance in Denmark. We sat in a mediocre coffee shop on the Westside of LA, where I told her about my father, grandmother, and aunt, and why I had waited my whole life to tell a story like this. We connected and she agreed to let me produce the film.

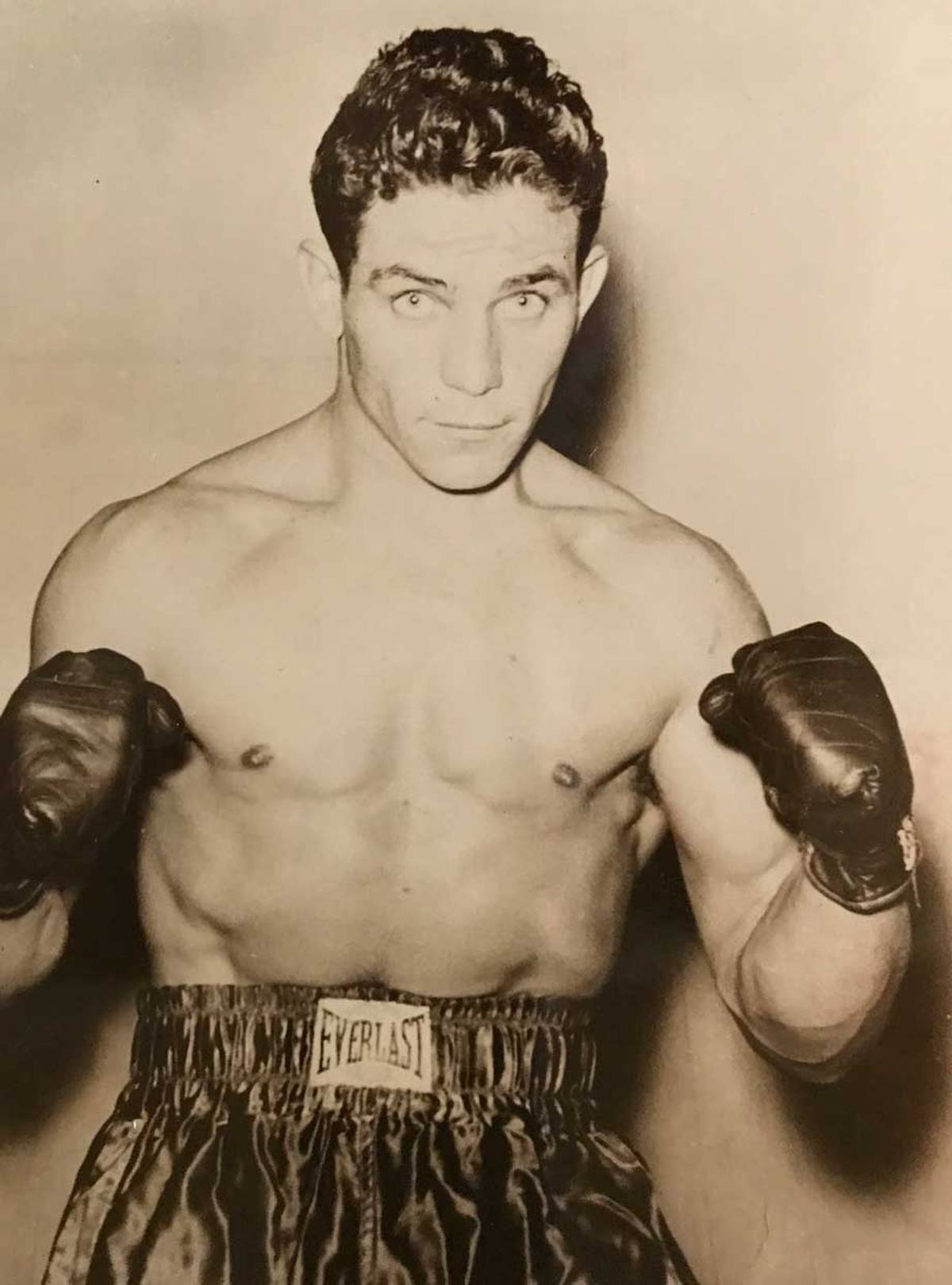

For someone like me, who had seen almost every feature and documentary about the Holocaust, I was surprised when I read the script about Harry Haft and realized I had never heard of him. The script has a simple story: Harry (Hertzke) is a Polish Jew from Belchatow who is sent to Auschwitz. An SS officer sees he has a good right hook and gives him the opportunity to fight for his life in the ring. The German is running a betting scheme and making money off his fellow officers and soldiers. The deal is: If Harry wins, he gets extra rations. If he loses, he dies (either he gets shot or sent to a gas chamber). Harry won over 70 fights in Jaworzno (the Germans called it Neu-Dachs, a subcamp of Auschwitz). Of course, around 70 of his opponents lost those fights, most of them Jews. And they were murdered by the Nazis.

Harry has a very specific reason to keep fighting—a woman, Leah, whom he met before the war. It is his love for her that motivates him to ultimately survive the camp and make his way to America, where the film mostly takes place. The subsequent narrative is about Harry’s PTSD and the price of being complicit in the killing of your own people. It’s about finding a life, even if it’s not the one you were looking for, and the redemptive power of having children in a world where so many died. It’s also about the burden they bear, as well as the victory that every son and daughter represent by their sheer existence.

The script is based on a book by Harry’s son Alan called Harry Haft: Survivor of Auschwitz, Challenger of Rocky Marciano, which recounts his father’s story simply but elegantly.

Alan Haft couldn’t be more different, but when I met him, I immediately felt I knew him. We have both spent our lives fighting imagined and invented enemies. It’s what you do when your father’s existence was predicated on survival against all odds. We will never have an enemy that threatens us the way they did our fathers, so life (as though it isn’t tough enough) must be made tougher. There must always be someone to prevail over. It’s shit, but it’s all we’ve known and because of it, I feel a deep kinship with Alan. When he tells me how tough Harry was on him, I immediately empathize. My father was tough on me, too. Upon induction into the Jewish Sports Hall of Fame, Harry Haft said his greatest regret was the damage he did with his fists.

For a few months I heard pitches from various respected directors. All of them were interesting, but none of them got me excited. Everything was a little too easy and reverent and full of sensitivity and understanding. And then one sunny day, Barry Levinson’s agent called and said that Barry was interested, and would I have lunch with him at the Four Seasons in Los Angeles. I mean, Barry Levinson? I’d seen every film he ever made—there are no bad ones, and the good ones are brilliant. You forget … Diner, Rain Man, Good Morning Vietnam, The Natural … Wag the Dog, Avalon, Tin Men, Liberty Heights, Bugsy … he directed all those amazing films.

At lunch, Barry was charming, avuncular, and full of great stories of the good old days in Hollywood, which he told better than anyone. But an hour into lunch, he still hadn’t said anything about the film. Finally, I asked him, “Why are you interested in this script?” and Barry slipped into another story with his singsongy cadence. He told me that when he was a kid, he had a great-uncle that came to stay with them in Baltimore and he slept in the same room as Barry. They didn’t have a guest room. Barry was maybe 5 years old. And in the middle of the night, his uncle would scream in his sleep in a foreign tongue and awaken Barry. I imagine a little boy and an older man, both terrified, both looking at each other in a dark child’s bedroom saying nothing. Later, when he was a teenager, Barry discovered that his uncle had “been in the Holocaust.”

So naturally, I asked Barry what camps he had survived, and what his story was. Barry didn’t know anything, which seemed incomprehensible to me. He explained that in his family they never talked about it, or anything to do with the old country, so he never asked. And that was the moment that I knew Barry Levinson was going to direct the film. He needed to understand what his great-uncle’s terror was about and what happened to him, a question that had been building inside him for 70 years.

After we started working on the film, I asked Barry for his uncle’s name. He told me his name was Sylvan Skurnik. “What’s his real name?” I asked. It couldn’t be Sylvan. He said he didn’t know. While preparing for the film, I had the benefit of connecting with some of the greatest Holocaust experts in the world and I knew that if I had the right information, we could find out what happened. But Barry didn’t have an answer.

Right before we started filming, I asked Aaron Gilbert, the chairman and CEO of Bron Studios, who financed the film, if I could take Barry and our core team to Auschwitz. True to form, Aaron, who is the most generous soul and a true friend of all artists, as well as a great producer in his own right, agreed to pay for a private plane from Budapest to Katowice and joined us. It was the only way we could get there and still make the shooting schedule.

Ben Foster and I sat across from each other and talked most of the short flight. Ben had worked with Barry 20 years ago, back when he was a kid, when Barry had cast him in Liberty Heights. In preparation for playing Harry, he would lose 62 pounds (to mirror Harry’s weight in the camp) and then gain 50 pounds of pure muscle (to mirror when Harry fought Rocky Marciano). At this point on the plane, he was already very thin, but the transformation that was occurring in him was much more than physical. The mood was jovial as we masked the feelings we were about to confront. I said, “This is how the Jews come back to Auschwitz, in a private plane.” It’s an oddly distasteful joke, but the subtext was “Fuck you Nazis, we survived!”

We landed and took a short van ride over to Auschwitz. It was a cold, gray morning. I had arranged a private tour by the director of the press for the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Pawel Sawicki, who had already connected us with archivists and historians at the museum. He was keen to meet us, to show us Harry’s records in the archive, and to give us the tour. The archivist wore white gloves and showed us the actual record of Harry’s name at Auschwitz. It was chilling.

I had been to Auschwitz before with my children and wife. I wanted them to have the experience and to connect with the place where their great-great-grandmother had been murdered. My son was only 11. There is a photograph of him standing on the train tracks at the camp, bundled up in a navy blue peacoat and a woolen Peruvian hat. I took it with the same feeling: Fuck you, Nazis, we survived. But something else occurred to me about that earlier trip. I was so focused on their experience that at some level I didn’t allow myself to have my own. I shared this with Ben, who encouraged me to face the moment myself and not worry about hosting.

The tour was long. It was cold. It was hard. Barry trudged on in uncharacteristic silence. When we got to the bombed crematorium where I had been told with certainty my grandmother had perished, I was buzzing with anxiety. Ben gave me a look. And then, I announced to the group that I was going to say Kaddish for my grandmother. It occurred to me that my atheist father never had. Really, no one ever had, and certainly not here. And a strange thing happened. Aaron announced that he wanted to say Kaddish for his grandfather, and though he hadn’t died there, it was an act of beautiful solidarity. Ben stood next to me. I wept. Barry watched quietly.

When we returned to Budapest, I received a brief email from Barry thanking me and telling me that it was a very meaningful trip. The next day, I asked him again for his uncle’s full name. He said, “Wait, let me text my sister.” Within minutes we had his full name. And within three days I had used my contacts to get a 40-page dossier on Simka Skurnik, Barry’s great-uncle, survivor of the ghetto at Pruzana, Auschwitz, Dachau, and the Landsberg DP camp. Simka had endured what few others had. And no one in his family ever dared to ask the question.

In The Survivor, Barry incorporated a monologue that is a famous story from Auschwitz, told to us by Pawel during the tour. It’s about a prisoner who loses his cap (an infraction punishable by death in the camp) and steals another prisoner’s cap, knowing that the man will die. And Barry wove this into a speech, delivered by Ben as only he could, about choices.

When I showed the film to Harry’s son Alan, I asked him what his father would have said had he seen it. Alan, never at a loss for words, paused for almost a full minute. And then he said. “Harry would have said, ‘I had a hard life.’”

I don’t know what my own father would have said. He would have tried to find some flaw perhaps, but I know he would have been proud that his son was trying to tell a complicated story. And Barry’s uncle Simka? I have no idea. But this film is to honor those three men, three heroes, three survivors: Harry Hertzke Haft, Simka Skurnik, and Moshe Arnošt Leshem.

This Yom HaShoah, The Survivor comes out on HBO and HBO Max.

Matti Leshem is the co-founder of New Mandate Films, a film and television production company created to mine the rich depth of Jewish history and literature.