Nabokov, Religion, and the Holocaust

The Russian American master and the anxieties of Jewish conversion

Horst Tappe; courtesy Fondation Horst Tappe

Horst Tappe; courtesy Fondation Horst Tappe

Horst Tappe; courtesy Fondation Horst Tappe

Horst Tappe; courtesy Fondation Horst Tappe

In the interview with Vladimir Nabokov, conducted in March 1963 for Playboy magazine, the writer Alvin Toffler asked: “As a final question, do you believe in God?” “To be quite candid,” Nabokov replied, “—and what I am going to say now is something never said before, and I hope it provokes a salutary chill—I know more than I can express in words, and the little I can express would not have been expressed, had I not known more.” This is, perhaps, Nabokov’s most readily quoted and paraphrased statement on religion. And yet, verbal charm and rhetorical decussation notwithstanding, what precisely is he saying? The critic Michael Wood believes that here “Nabokov himself sounds quite a bit like Adam Falter,” a character in Nabokov’s last Russian-language fiction “Ultima Thule” (1940), who is bent on both revealing and concealing a metaphysical discovery.

For a Russian aristocrat of his standing, Vladimir Nabokov inherited a diversity of past religious backgrounds, notably Lutheranism on the side of his paternal German ancestors and Judaism on the side of his maternal great-grandfather Nikolai I. Kozlov. There was also a strong sectarian streak in the family, and not only the Old Believers roots of Nabokov’s maternal grandfather, Ivan Rukavishnikov of the gold-mining fortune. In exile Nabokov’s mother, Elena I. Nabokova, embraced Christian Science. Less known is the fact that Nabokov’s maternal uncle Vasily Rukavishnikov was a passionate Pashkovian, as they called the followers of the Granville Waldegrave, 3rd Baron Radstock, one of the founders of the evangelical movement in Russia.

Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy

A Russian Orthodox Christian (although not a practicing one) married to an unconverted (though not an observant) Russian Jew, Véra Nabokov (née Slonim), Vladimir Nabokov regularly returned to the topics of religious transformation and religious conversion in his letters and autobiographical writing. His views of religious conversion, however, would be less interesting if they didn’t set some of the central axes of his Russian- and English-language fiction. Aspects of mimicry in nature fascinated and excited Nabokov as “signs and symbols” of complexity and beauty. Mimicry in society, and especially religious mimicry—from dissimulation to conversion—reminded him of the unresolved—unresolvable—contradictions of his own family and marriage. Forming an imperfectly monosyllabic pair in both of Nabokov’s main languages, two of Nabokov’s great novels, the Russian-language The Gift (Dar, partially serialized 1937-38, complete book edition 1952) and the English-language Pnin (partially serialized 1953-55, complete book edition 1957), clamor to be recognized for their dynamic exploration of the religious conversion of Jews born in the former Russian Empire. Structural differences and compositional ambitions apart, in a number of ways The Gift, including its abandoned Part 2, could be considered a pre-Shoah dress rehearsal of Pnin.

Set in Weimar Berlin although also taking the readers on real and imaginary trips to Russia, Siberia, and to Central Asia, The Gift documents the artistic and personal growth of the Russian émigré aristocrat Fyodor Godunov-Cherdyntsev. Fyodor’s success as a writer is inextricably linked to his relationship with Zina Mertz, a product of a mixed, Jewish and Russian marriage. In The Gift, Nabokov explicitly connects mixed marriages and Jewish conversion with the trajectory of his quasi-autobiographical protagonist by placing Fyodor in close contact with the Chernyshevski family of Jewish Russian émigrés and by endowing his love for Zina Mertz with vatic significance.

The Jewish grandfather of the fictional Alexander Chernyshevski is said to have been baptized by a proselytizing Russian Orthodox priest, the father of the historical Nikolai G. Chernyshevski, utilitarian aesthetician and prominent radical of the Russian 1860s, whose critical martyrology Fyodor writes, and Nabokov includes as a chapter in the novel. As a part of the conversion, Chernyshevski the priest apparently lent the new Orthodox Christian his last name. For Alexander Chernyshevski, much like for about 70,000 Jews who were baptized in the Russian Orthodox Church throughout the 19th century (as the historian Michael Stanislawski calculated), their acquired religion amounted to an illusory ticket to the mainstream. Culturally a Russian, and spiritually an agnostic, Chernyshevski hovers between his ancestral Judaic past and his assimilated and displaced present. Despite a stated materialism and secularism, the fictional exile Chernyshevski, who goes insane following his queer son’s suicide, becomes Nabokov’s agent of exploring the metaphysics of death.

Chernyshevski, a secularized Orthodox Christian of Jewish extraction, voices skepticism about Christian notions of the afterlife through a parodic evocation of the Sermon on the Mount: “If the poor in spirit enter the heavenly kingdom I can imagine how gay it is there. I have seen enough of them on earth. Who else makes up the population of heaven? Swarms of screaming revivalists, grubby monks, lots of rosy, shortsighted souls of more or less Protestant manufacture—what deathly boredom!” On the eve of his death, in a “moment of lucidity,” Chernyshevski utters: “What nonsense. Of course there is nothing afterwards.” With “extreme distinctness,” he repeats: “There is nothing. It is as clear as the fact that it is raining.”

One of the surprises Nabokov has in stock for us is that Chernyshevski “had turned out at the last minute to be a Protestant,” and in the Russian original, Nabokov specifies that Chernyshevski was a Lutheran. Toward the end of the funeral service for Chernyshevski, Fyodor goes out onto the street. Behind the crematorium, he spots “turquoise turrets of a mosque” and “green cupolas of a white Pskovan-type church.” (Pskov is an ancient Russian city.) What is the meaning of the references to Islam and Russian Orthodoxy, and of the missing reference to the Judaism of Chernyshevski’s ancestors? Does Chernyshevski’s religious affiliation with Protestantism, and not Russian Orthodoxy, highlight his pro forma Christianity, his conversion in a minor key, through a ritual that does not require a public disavowal of one’s ancestors, as mandated in an Eastern Christian conversion? It’s possible that Chernyshevski’s Lutheranism also betokens the experience of Russian Jews—such as Nabokov’s former tutor Filipp Zelenski, a Lutheran by necessity—who sought to bypass the official czarist quotas yet weren’t prepared to go through with a Russian Orthodox conversion. It may also signal Nabokov’s disapproval of the opportunism of a new member of the Russian Orthodox Church with Jewish roots who becomes a Lutheran in Germany so as to assimilate further. If so, such authorial vexation with the double convert living in Weimar Berlin must be tempered with the afterknowledge of what might befall Chernyshevski in Nazi Berlin in 1937-38, when Nabokov actually wrote The Gift.

Twenty-five years ago I wrote of Zina as Fyodor’s Jewish muse; I have since come to feel that it might have been a wishful oversimplification. The entire novel becomes, in the words of its protagonist, “a kind of declaration of love.” And yet it’s hard to read The Gift without anticipatory bitterness, just as it’s difficult to dispel thoughts about the Shoah while reading the passage in Speak, Memory, in which Nabokov writes of watching trains, with his Jewish wife and young son, in Berlin in 1936-37 and in Paris in 1938-40.

In the course of the novel, Fyodor rents a room in the Berlin apartment where Zina lives with her mother and stepfather, Boris Shchyogolev, whom Zina’s mother married after the death of her first husband and Zina’s father, Oscar Mertz. A former prosecutor, Shchyogolev exemplifies the repugnantly burlesque Russian antisemitism of Jewish jokes, mock-Yiddishisms, and leisurely meanderings on the subject of an international Jewish conspiracy. At one point, believing Fyodor to be a hundred-proof Russian always open to antisemitic talk, Shchyogolev offers him an analysis of the Jewish impact upon his wife and step-daughter: “My better half ... was for 20 years the wife of a kike and got mixed up with a whole rabble of Jew in-laws [tselym kagalom]. … Zina (he alternately called his stepdaughter either this or Aïda, depending on the mood), thank God, doesn’t have anything specific—you should see her cousin, one of these fat little brunettes, you know, with a fuzzy upperlip.” Aïda is a double play on the Yiddish a id, a Jew, and on the name of the captive Ethiopian’s girl in Verdi’s eponymous opera. Shchyogolev even speculates that Zina is a progeny of her mother’s extramarital affair with an ethnic Russian. Zina, in turn, imparts Fyodor quite a different image of her father: “In her version the image of her father took on something of Proust’s Swann.” She fashions her deceased father as a Jewish aristocrat, a “refined, noble, intelligent and kindly man” who recited “Homer by heart.”

While the prewar, “Russian” Nabokov lacks the vocabulary to express that, halachically speaking, Zina would not even be considered Jewish, he shows with precision that religion barely surfaces in her discussions of her identity. In fact, the wife of Alexander Chernyshevski points out to Fyodor that Zina does not care “very much to admit her origins,” which would discordantly place Zina in the same category as other assimilated Jews whom Nabokov chides for their self-abnegation. Nabokov also notes that Zina’s sense of Jewishness is not without revealing contradictions, and she has a complicated relationship with her own roots. To Zina, her Jewish boss was “a German Jew, i.e. first of all a German.” Looking for vestiges of the historical Véra Nabokov, whose father refused to convert even if it meant giving up law practice in czarist Russia, may result in disappointment. I don’t think it’s been noted that Nabokov’s novel knows, without being overexplicit about it, that Zina’s Jewish-born father would have had to convert in order to be able to marry Zina’s Russian Orthodox mother, and that Zina was likely born to two Christian parents. This does not rule out the possibility of Zina’s return to Judaism, and in fact Nabokov might have heard not only of Arnold Schoenberg’s conversion to Lutheranism in 1898, but of the composer reaffirmation in 1933 in Paris, at which Marc Chagall served as a witness.

There are many reasons why The Gift starts and ends in Weimar Berlin. Even though Nabokov composed the novel after the passage of the Nuremberg Laws, and had completed it in January 1938, nine months before Kristallnacht, he chose to give Fyodor and Zina a chance at the kind of tremulous happiness that the ending communicates. In Weimar Berlin Fyodor and Zina could be married in a civil ceremony, they way Vladimir and Véra had been married in 1925. A historical scrutiny of The Gift yields gestures of preemptive fear and despair that Nabokov also performed in his other fiction of the 1930s.

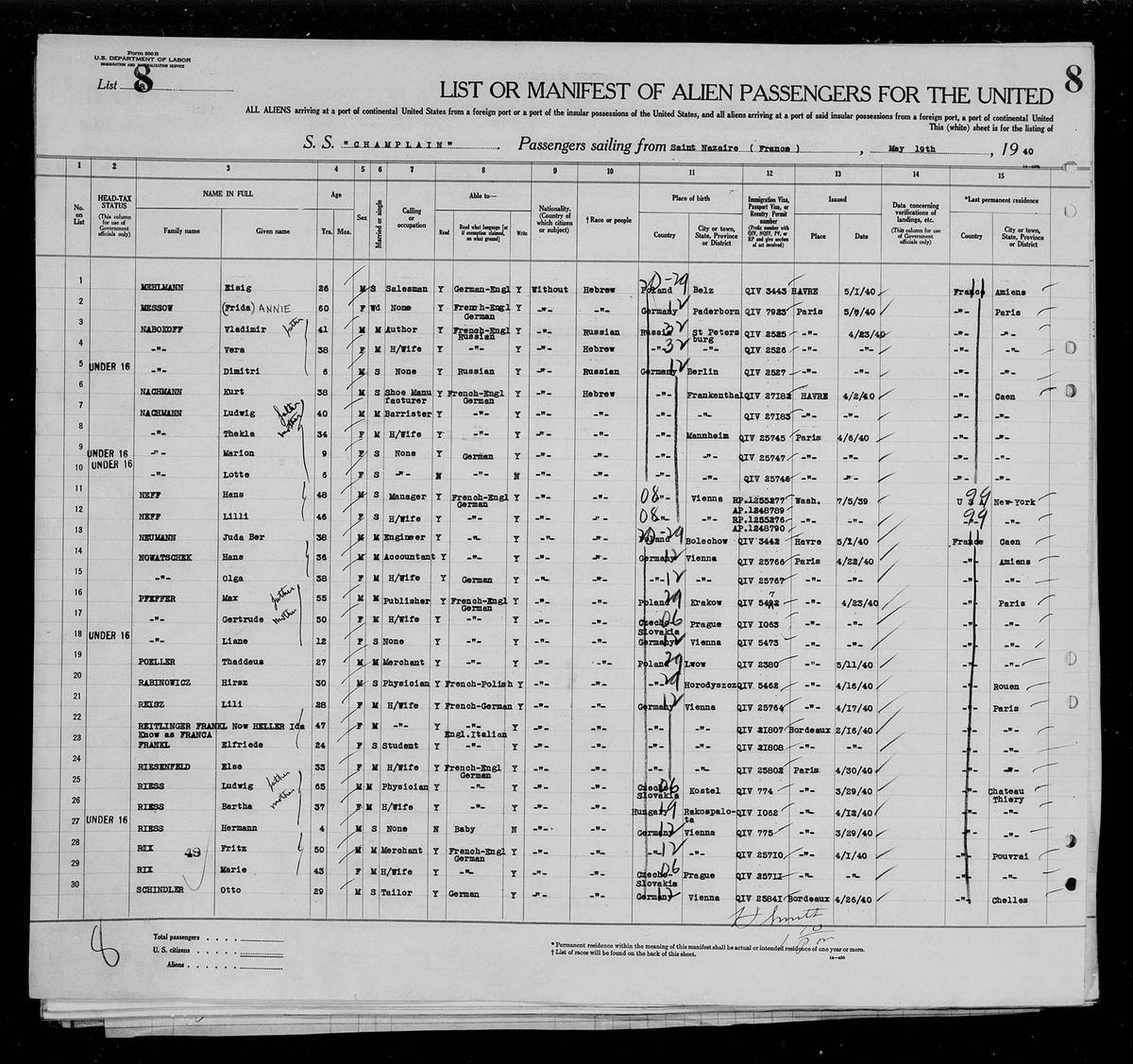

Ellis Island Records

Nothing in all of Nabokov’s pre-1940 oeuvres offers such a crushing defeat of hope as the surviving archival pages of Part 2 of The Gift, which Nabokov penned either in Paris in the months preceding the escape to America or already in America soon after having arrived there as a refugee with his “Hebrew” wife and “Russian” son. (This is how Véra Nabokov and Dmitri Nabokov are listed in the manifest of the S.S. Champlain, the vessel that carried the writer and his family from Saint-Nazarre to America in May 1940.) The Nabokovs’ own marital discord, framed by the advent of World War II and the Shoah, seeps into Part Two of The Gift. Zina and her husband Fyodor are living in Paris in the late 1930s; they are poor and childless. Their marriage is on the rocks, Fyodor is having an affair with a French prostitute by the name of Yvonne. Zina, whose own sense of Jewishness has acquired combative dimensions, rebuffs a Russian fascist who stops by to see her husband by telling him she is “a Jewess.” In the autumn of 1938 Zina dies in Paris, run over by a car—perhaps more of an authorial rescue from encroaching history. What, indeed, awaited a Russian refugee of Jewish descent in occupied Paris? Perhaps survival and escape? But more likely, Vél d’Hiv, deportation to Drancy, Pithiviers or Beaune-la-Rolande and then a transport to Auschwitz. With Zina’s death, Nabokov’s novel, too, has nowhere to go, and the story of a mixed, Jewish-Russian marriage, gains a devastating, dispiriting finale.

During the interwar “Russian” years, Nabokov generally regarded religious conversion as an act of violence against one’s origins and true self—a bit like he would later consider Freud and Freudianism to be “crude” and “medieval.” In America, after World War II and the Shoah, Nabokov became less judgmental of religious conversion, and his novel Pnin offers unparalleled evidence of Nabokov’s writing under the burden of guilt and trauma.

Set in the early 1950s, mainly on a college campus on the Eastern Seaboard, and striated with émigré recollections and reconstructions, Pnin (which is my own favorite of Nabokov’s novels) is simultaneously a wry campus comedy, an immigrant chronicle of translingual perils and pleasures, and one of the first American novels about the memory of the Shoah. Pnin originated, emotionally, in Nabokov’s guilt over and expanding knowledge about the deaths of his brother Sergey, a gay man who had converted to Catholicism in 1926 in Paris, and of a number of Jewish Russian émigré authors, some of them Jewish converts to Christianity, in the Nazi camps and prisons. They included the Parisian poets Yuri Felzen and Yuri Mandelstam and the Parisian editor and philanthropist Ilya Fondaminsky (Bunakov), all three of whom in 1942-43 were sent from Drancy to their death at Auschwitz. Nabokov took some of the tangible features of Mira Belochkin, the novel’s female heroine and professor Pnin’s youthful love, and of her family members, from his former Berlin acquaintances, the poet and medievalist Raissa Bloch (Gorlin) and her husband Mikhail Gorlin, a literary scholar and author. In July 1942 Mikhail Gorlin was taken from Pithiviers to Auschwitz, where he was murdered on Sept. 5, 1942. Raissa Bloch attempted to cross the Swiss border from France on Oct. 18, 1943. After the Swiss border police returned her to France she was taken to Drancy, from which she was deported on Nov. 20, 1943. She was probably gassed upon arrival to Auschwitz; as the research of the Vienna-based scholar Fedor Poljakov demonstrates, the exact record of Bloch’s death remains unknown.

In the judgment of Brian Boyd, the don of Nabokovians, “of all Nabokov’s novels, Pnin seems the most amusing, the most poignant, the most straightforward.” I’m not sure I would agree with the third part, and especially when it comes to the novel’s presentation of questions of Jewish identity, Jewish conversion, and mixed marriages of Jews and Christians. While in the published Part I of The Gift Nabokov is overexplicit about the origins of Fyodor Godunov-Cherdyntsev in the pre-Petrine Russian nobility and a bit uncertain about the contours of Zina Mertz’s Jewish identity, he delivers the information about the ancestry and identity of professor Timofey Pnin only gradually and in puzzle pieces that, when we have finally fit them together, form a picture that’s hardly straightforward.

Timofey Pnin is often regarded as both a quintessential Russian intelligent and Nabokov’s idealized gentile. In a 1955 letter to the editor of Harper & Brothers (which rejected the novel), Nabokov wrote about his Pnin: “A man of great moral courage, a pure man, a scholar and a staunch friend, serenely wise, faithful to a single love, he never descends from a high plane of life characterized by authenticity and integrity.” Critics, and I myself have been guilty of this, have linked Pnin’s moral trepidation with his survival as a non-Jew. Pnin experiences profound guilt over living in the post-Shoah world, in which the murder of Mira Belochkin, his Jewish beloved, was permitted. A deeper scrutiny of Pnin’s origins suggests that Nabokov gives the reader just enough, or perhaps more than enough, to discover that Pnin may be a product of a mixed marriage and the son of a Jew who converted to Russian Orthodoxy.

From what’s stated in the novel, Pnin’s father, an ophthalmologist with the Chekhovian first name and patronymic Pavel Antonovich Pnin, is married to a woman named Valeria, daughter of the revolutionary Umov and a German woman from Riga. A close friend of Pnin’s father is the Jewish pediatrician Yakov Grigorievich Belochkin, and from their pre-revolutionary encounters with the young aristocrat Vladimir Vladimirovich, we get the distinct sense that they belong to a different social stratum, which I’m inclined to define as the milieu of Jewish university graduates, some of whom had to convert back in the 1880s-1890s so as to circumvent the anti-Jewish quotas. According to the research of the Russian Israeli historian Mikhail Beizer, in the 1910s, about 17% of all doctors in St. Petersburg were Jewish. My own examination of Petrograd’s directory for 1916 (the city had been renamed after the start of World War I), the year of Timofey Pnin and Mira Belochkin’s romance, revealed that some 30% of the city’s 91 ophthalmologists had Jewish-sounding names. Pnin’s father, Nabokov’s narrator tells us, once treated Leo Tolstoy, and this may also be a hint at Dr. Grigori Birkengeim, a Jewish doctor who attended to Tolstoy’s family.

Wikimedia

Pnin’s last name, not easily pronounceable for a native speaker of English, is usually treated as a truncated one (from Repnin or Cherepnin, and perhaps signaling his ancestor’s illegitimate birth) or as one derived from the Russian noun pen (tree stump). However, the last name Pnin also suggests a Hebrew origin and a meaningful connection with Pnina (Peninnah פְּנִנָּה Pəninnā), a character in the Hebrew Bible. (While composing his novel in English in early 1950s America, Nabokov, who had toyed with the Hebrew alphabet as a young writer, must have had in mind the Peninnah of the Hebrew Bible rather than Fennana, the name’s Greek-influenced Church Slavonic transliteration.) In Samuel 1, we read of Elkanah and his two wives, Hannah and Peninnah. Peninnah has children whereas Hannah, whom Elkanah loves, is initially childless.

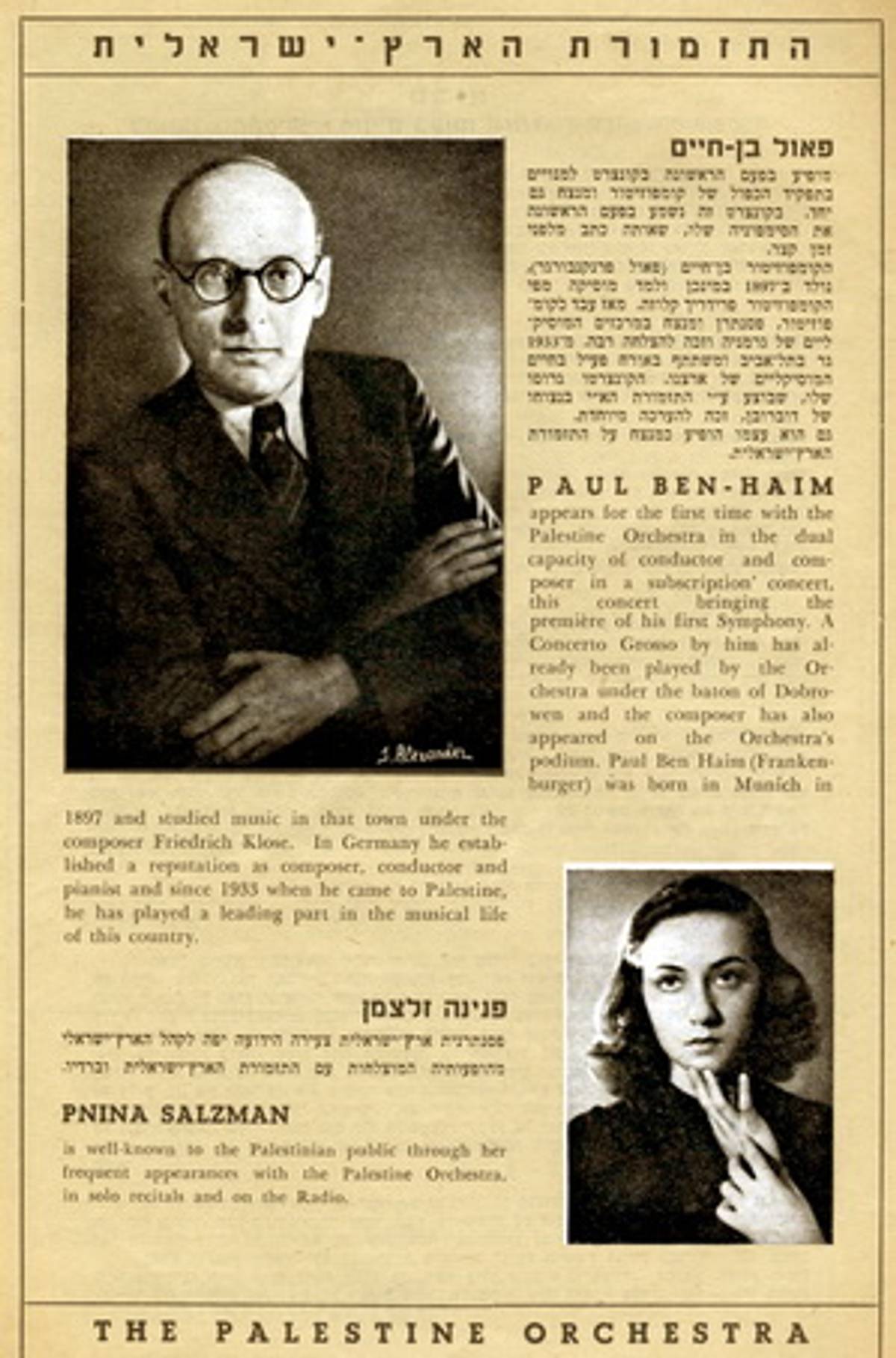

Different midrashic sources regard Peninnah as either spiteful or as the one who incites Hannah and helps her conceive and give birth to Samuel, future prophet and seer. Phonetically, the connection to Penninah and not just to punning is brought out already in the novel’s opening pages, during Pnin’s reading at Cremona, when he is introduced as “Professor Pun-neen.” Since the 1950s Pnina has become a fairly common modern Hebrew name, as in Pnina Tornai, the famous Israeli fashion designer. But Nabokov may have heard, perhaps through his Parisian émigré connections or the musical studies of his son Dmitri, of the great Israeli pianist Pnina Zalzman, who was born in Tel Aviv in 1922 to Jews from the former Russian Empire and as a child prodigy studied in Paris in the 1930s.

Wikimedia

At the same time, as if to underscore the contrapositions of a Jewish-gentile marriage, Timofey Pnin’s first name, patronymic, and background suggest a vital connection with Saint Timothy of Ephesus and with conversion of Jews. Timótheos (Τιμόθεος, “God has honored”) is the exact Greek equivalent of the Hebrew Johannon (יְהוֹחָנָן). The émigré scholar Gennady Barabtarlo, who was the first Russian translator of Pnin, and also the British researcher Erik Eklund and the American poet and critic Matthew Roth, have emphasized Nabokov’s reliance on the 16-volume compendium, The Lives of the Saints, by Rev. Sabine Baring-Gould, specifically on the 1914 Edinburgh edition. To quote the article on St. Timothe of Ephesus in Baring-Gould’s Lives:

Saint Timothy, the beloved disciple of S. Paul, was born at Lystra in Lycaonia. His father was Gentile, but his mother, Eunice, was a Jewess. She, with Lois, his grandfather, embraced Christianity, and S. Paul commends their faith. S. Timothy made the writings of the Old Testament his study from infancy. S. Paul took the young man as the companion of his labours, but he first had him circumcised at Lystra, as a condescension to the prejudices of the Jews. … When S. Paul was compelled to quit Beræa, he left Timothy behind him to confirm the new converts. … During the subsequent imprisonment of S. Paul Timothy appears to have been with him. He was ordained Bishop of Ephesus, probably in the year 64. … S. Timothy was afterwards [after the death of S. Paul] associated with S. John; and in the Apocalypse he is the Angel, or Bishop, of the Church of Ephesus, to whom Christ sends His message by St. John.

Baring-Gould and other commentators discuss the conversion of the Jews and stress Paul’s fatherly religious love for Timothy, to whom he refers to as “my true child in faith” (1 Timothy 1:2).

Inverting the story of St. Timothy’s genetic and religious origins, Nabokov may have given Timofey Pavlovich Pnin a Jewish converted father and Gentile mother to rhyme with Zina Mertz’s origins in The Gift. Son of a Jewish mother and a Greek father, Saint Timothy was baptized by Saint Paul to become his close associate. Two of Paul’s letters to Timothy are part of the New Testament, and Acts of the Apostles devotes significant attention to Timothy. A separate, apocryphal text, focuses on Timothy’s acts. Paul, himself a Jewish convert whose name used to be Saul, serves as Timothy’s spiritual father. In Chapter 4 of Nabokov’s novel, Victor, son of Pnin’s casually antisemitic ex-wife, a young man for whom the childless professor feels a surge of fatherly affection, visits Pnin in the college town of Waindell. During Victor’s visit Pnin says to Victor in English: “‘My name is Timofey … Timofey Pavlovich Pnin,’ which means ‘Timothy the son of Paul.” This Nabokovian clue has been curiously overlooked by Nabokov’s students. Only the Hungarian critic Márta Pellérdi has discussed Pnin’s connection to St. Timothy and St. Paul, although without reference to Timothy’s Jewish origins and conversion.

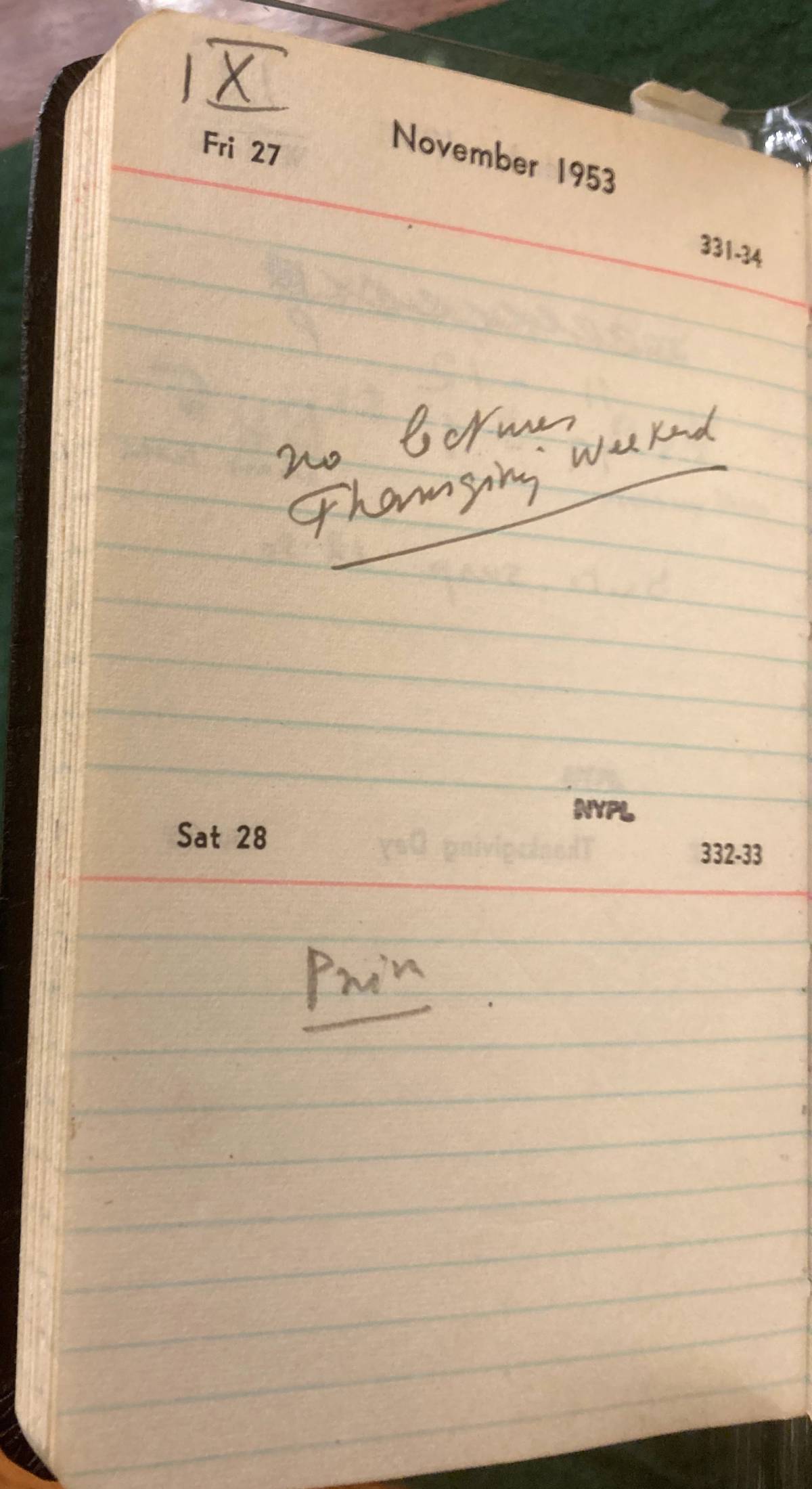

Berg Collection, New York Public Library

Twice in the novel, Pnin, whose name may be anagrammatically linked to “epiphany” and to “nimb,” is referred to as a “saint.” Thinking of Timothy, a martyred early Christian saint at the time when many Christians came from the Jewish communities, also puts the reader in conversation about the lot that Pnin escapes by having fled from Europe, and about Pnin’s failed attempts to dwell in the survivor’s silence of unremembrance. Not only Mira Belochkin’s death in the Shoah but the deaths of close friends and colleagues haunt Pnin. At the end of Chapter 4, he has a dream of “pacing a desolate strand with his dead friend Ilya Isidorovich Polyanski as they waited for some mysterious deliverance to arrive in a throbbing boat from beyond the hopeless sea.” (Yuri Leving, who teaches literature at Princeton, originally noted that the name Ilya Isidorovich memorializes Ilya Isidorovich Fondaminsky.) In Chapter 5, at a colorful gathering of émigrés at The Pines estate, Pnin encounters the survivors Samuil Lvovich and Roza Abramovna Shpolyanski, in whose last name one hears an echo of Pnin’s deceased friend Polyanski. Against Pnin’s express wishes, Madame Shpolyanski forces him to remember Mira. Visions of the Shoah pursue Pnin, and he sees “ditches and ravines gaping on either side” of the road as he drives up to The Pines. The Shoah context also links Pnin, in part by way of the deaths of Jewish converts who became Christian saints, to the martyrdom of his émigré loved ones.

In his autobiographies, Nabokov spoke of Fondaminsky, who had been an early herald of Nabokov’s talent and his benefactor, as “a saintly and heroic soul,” and in the foreword to Glory, penned in 1970, Nabokov specified Fondaminsky’s conversion: “He was a Social-Revolutionist, a Jew, a fervent Christian … later murdered by the Germans in one of their concentration camps) … .” Fondaminsky, who hesitated to take baptism for several years after his wife’s death in 1935, became a member the Orthodox Church in the Royallieu-Compiègne internment camp in 1941. According to some evidence, Fondaminsky refused to entertain the possibility of an arranged escape because he wanted to remain with fellow Jews. He was murdered in Auschwitz on Nov. 19, 1942. In 2003 Elias (Ilya) Fondaminsky of Paris was pronounced Saintly Martyr by the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, along with three Russian Orthodox emigres who in 1941-42 actively assisted with the rescue of Jews, were arrested, and died in Nazi camps—Mother Maria (Skobtsova), her son Yuri Skobtsov, and Father Dimitri Klepinin.

Wikimedia

How would have Nabokov reacted, if he had lived to see his Jewish-born friend Ilya Fondaminsky canonized as an Eastern Orthodox Saintly Martyr? I believe Nabokov would have found offensive the postwar comments by those Russian émigrés who spoke of Fondaminsky’s “expiatory” path to Christianity. In her diary entry for Sept. 3, 1945, Vera Muromtseva-Bunina, wife of Nabokov’s literary master Ivan Bunin, who in 1933 became the first Russian writer to receive the Nobel Prize in literature, records a conversation with another émigrée about Fondaminsky’s last months in the transit camp and his death in Auschwitz: “Muza is also certain that Ilyusha willingly embraced the suffering, regarded it as a redemption.” In 1965 Nabokov lashed out at his friend Roman Grinberg, editor of a New-York-based émigré magazine, for publishing an epigrammatic fable from the 1930s that had been aimed at Raissa Bloch and Mikhail Gorlin: “… given the tragic and inexpiable fate of the Gorlins, it probably shouldn’t have been published.”

Aside from Nabokov’s pathological if principled dislike of Boris Pasternak, a Russian Jew who in the Soviet 1940s-50s fashioned himself as an Orthodox Christian and expressed supercessionist views in his novel Doctor Zhivago, the post-Shoah Nabokov of the American and Swiss years became less condemnatory of converts and conversion. Pnin shows that while retaining a measure of skepticism about the ethics of religious conversion, Nabokov was prepared to see it in a more gentle, more forgiving way. Consider the scene where Pnin goes for a swim in the country. The episode is doubly marked by the presence of professor Chateau, Pnin’s close friend with a Kafkaesque last name, and a “score of butterflies,” implying the witnessing absence of Vladimir Vladimirovich:

“Oh no,” said Chateau. “You will lose it some day,” he added, pointing to the Greek Catholic cross on a golden chainlet that Pnin had removed from his neck and hung on a twig. Its glint perplexed a cruising dragonfly.

“Perhaps I would not mind losing it,” said Pnin. “As you well know, I wear it merely from sentimental reasons. And the sentiment is becoming burdensome. After all, there is too much of the physical about this attempt to keep a particle of one’s childhood in contact with one’s breast bone.”

“You are not the first to reduce faith to a sense of touch,” said Chateau, who was a practicing Greek Catholic and deplored his friend’s agnostic attitude.

While especially touching, Pnin’s use of the preposition “from”—“from sentimental reasons”—also highlights two possibilities: Pnin’s impulse to reaffirm his Jewishness, and the opposite of it, a baptismal immersion and a reaffirmation of his Christianity, and therefore a stubborn loyalty to his Jewish father’s choice to convert.

In Nabokov’s notebooks, one comes across an entry titled “Human Interest,” from May 1962, occasioned by the publication of Pale Fire. Now at the peak of his fame and acclaim, Nabokov lists some of the activities he does not engage in (or, to be precise, purports not to engage in): “Mr N. does not: drive a car, operate a typewriter, play golf, listen to music, endorse books, sign books, co-sign declarations, eat oysters, get drunk, go to church, go to analysts, take part in demonstrations.” Right below, under the rubric Pale Fire and the date of May 28, 1962, Nabokov adds: “This book will not please vulgarians, lovers of D.H. Lawrence, champions of the Social Comment School of Fiction, homosexuals, symbols seekers and sovietophiles, and the kind of solemn reader who dots every ‘I’ in a novel with the author’s head.” Nabokov’s two-part credo simultaneously offends and gladdens the liberal imagination as it augments the maddening contradictions of his authorial statements.

Gavriel Shapiro, professor emeritus of Russian literature at Cornell, where Nabokov taught in the late 1940s and 1950s, argues that “in later years, with the rise of fame that resulted in his high exposure, Nabokov, a very private individual, communicated his faith in God in the circuitous (chiastic) and even e contrario manner.” In the 1960s-1990s, a wave of critical literature had practically washed out considerations of Nabokov’s religion—religion as opposed to personal spirituality or cloudy metaphysics. Countering this trend, Samuel Schuman, who did exemplary work on Nabokov and Shakespeare, wrote in 2000: “I suggest that a next question is: what is the connection between Nabokov’s religion … and Religion? … Is Nabokov, in some sense, a Christian?” As part of his evidence, Schuman revisited the passage at the end of Chapter One of Speak, Memory, in which the American Nabokov idealizes the Russian imperial past through the tears of remembering his father. In doing so, Nabokov engages with Eastern Orthodox religious imagery while describing a group of grateful peasants at the Vyra estate south of St. Petersburg who are tossing his father in the air:

From my place at table I would suddenly see through one of the west windows a marvelous case of levitation. There, for an instant, the figure of my father in his wind-rippled white summer suit would be displayed, gloriously sprawling in midair, his limbs in a curiously casual attitude, his handsome, imperturbable features turned to the sky. Thrice, to the mighty heave-ho of his invisible tossers, he would fly up in this fashion, and the second time he would go higher than the first and then there he would be, on his last and loftiest flight, reclining, as if for good, against the cobalt blue of the summer noon, like one of those paradisiac personages who comfortably soar, with such a wealth of folds in their garments, on the vaulted ceiling of a church while below, one by one, the wax tapers in mortal hands light up to make a swarm of minute flames in the mist of incense, and the priest chants of eternal repose, and funeral lilies conceal the face of whoever lies there, among the swimming lights, in the open coffin.

Writing about Nabokov’s “faith,” the Prague-born scholar Sergei Davydov concluded: “In many respects, Nabokov’s deviations and eventual apostasy from Christianity remind one of the gnostic heresy, various elements of which found their way into his early poetry …” Apostasy as a renunciation and abandonment of one’s religious beliefs in favor of another religion is, of course, a serious charge. Nabokov himself employed the term in the last four lines of the long poem “An Evening of Russian Poetry” (1944). He used “apostasy” and its cognates in reference to a Russian poet’s Anglophone practices, but the translingual poem itself refused to live apostatically:

Bessónnitza, tvoy vzor oonyl i shtráshen;

lubóv moyá, otstóopnika prostée.

(Insomnia, your stare is dull and ashen,

My love, forgive me this apostasy.)

Vladimir Nabokov was many things, but an apostate (Russian, otstupnik) he was not. In a letter of July 18, 1926, sent from Berlin to a sanitarium in St. Blasien in the Black Forest, where Véra Nabokov was undergoing treatment most likely after a miscarriage, Nabokov mentioned relaxing in the Grunewald and encountering a boy, who saw a cross on his neck and said one word: “Christ.” We don’t know exactly when Nabokov stopped wearing his Russian Orthodox cross, but we do know how he fundamentally felt, even after World War II and the Shoah, about renunciating one’s origins, one’s parents, and their religion.

Early on in Pnin, Vladimir Nabokov places the eschatological cart before the novelistic horse. “Death is divestment, death is communion,” states Vladimir Vladimirovich, the famous Russian American writer under whose tutelage “poor Pnin” adamantly declined to live and work. Nabokov died on July 2, 1977 in a hospital room in Lausanne, a plain crucifix affixed over the hospital bed. He did not receive the last rites. And yet Nabokov was and remained a Christian, and he rescued two Jews he loved the most from a likely death. That was more than what the vast majority of the world’s devout and observant Christians were prepared to do during the Shoah.

Courtesy the Berg Collection, Nabokov Public Library

Were Nabokov’s religious doubts dispelled or reaffirmed, post-mortem? What and whom did he encounter in the afterlife? A “nothing” of the ex-Jewish Lutheran Alexander Chernyshevsky? A heavenly kingdom of the “gentle young rabbi” who died “on a Roman crux,” to use the formulation of Bend Sinister’s philosopher Adam Krug, who is married to a non-Jewish woman? An “autocratic God,” to whom Pnin could no longer subscribe after the Shoah? A “democracy of ghosts,” which Pnin believed, albeit “dimply.” A committee of the “souls of the dead” overseeing the “destinies of the quick” …

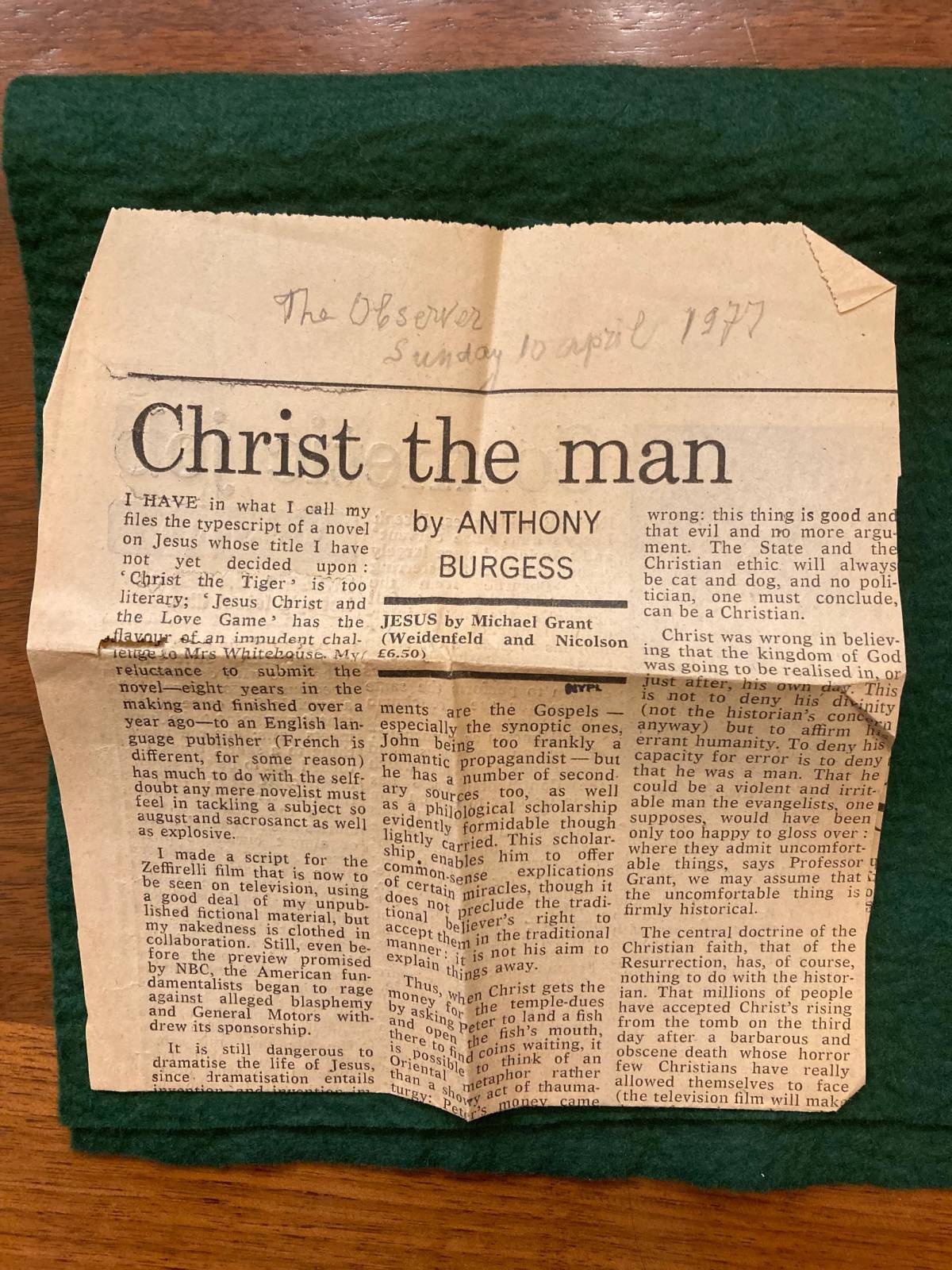

Preserved in Nabokov’s last notebook is a yellowed clipping of an article from The Observer, the world’s oldest Sunday newspaper and one the writer had been reading since his Cantabrigian days. Across the top, in pencil, Nabokov wrote: “The Observer Sunday, 10 April 1977.” It is a review, by none other than Anthony Burgess of A Clockwork Orange, of Jesus by Michael Grant, a renowned historian of the ancient world. The review is titled “Christ the Man.” Nabokov made no mention of the review in his notebook. As the calendar approached the 2nd of July, the pages of Nabokov’s notebook grew silent.

Maxim D. Shrayer is a bilingual author and a professor at Boston College. He was born in Moscow and emigrated in 1987. His recent books include A Russian Immigrant: Three Novellas and Immigrant Baggage, a memoir. Shrayer’s new collection of poetry, Kinship, will be published in April 2024.