The Life of a Court Jew

Glikl of Hameln’s writings say much about Jewish commercial families in Central and Western Europe in the 17th and early 18th centuries

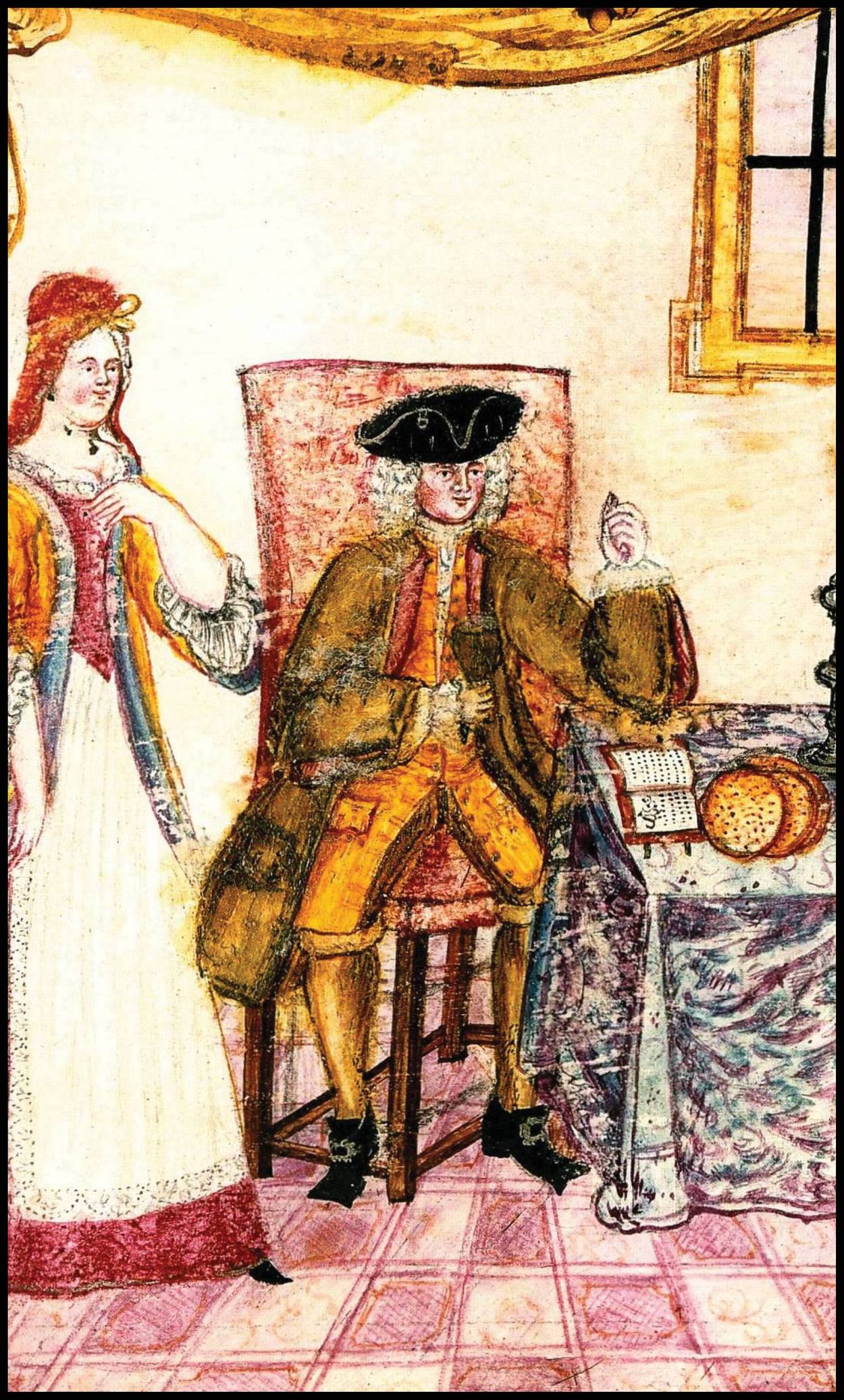

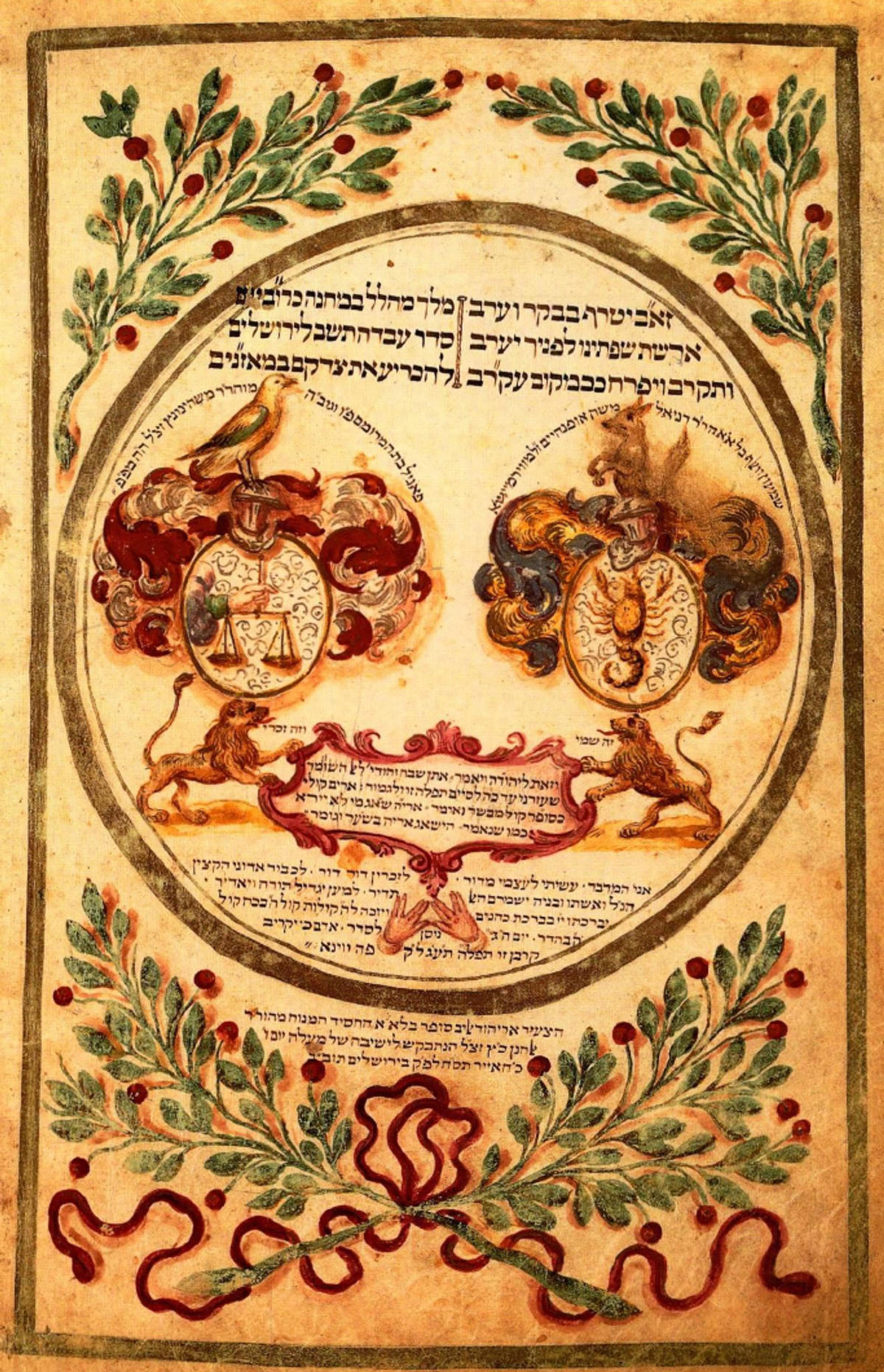

“He stands so high in esteem of the Prince Elector, may his glory be enhanced, and does so much business with him that I believe that if God, may His name be praised, does not turn against him, he will be the richest man in all Ashkenaz when he dies.” Thus wrote a Jewish merchant woman of Hamburg at the end of the 17th century as she recounted her life to her children. The esteemed man was Judah Berlin, also known as Jost Liebmann, then at the height of his career at the court of Friedrich, elector of Brandenburg. The woman was “Glückel von Hameln,” or rather, as she was called in Yiddish of her own day, Glikl bas Judah Leib, Glikl daughter of Judah Leib.

The seven books of Glikl’s Yiddish autobiography tell much about the lives and mentalities of Jewish commercial families in Central and Western Europe in the 17th and early 18th centuries, including those headed by men who lent to or otherwise provided for the needs of princely rulers. We will use Glikl’s writing here not for an overall view of Court Jews but for an example of how Court Jews entered into people’s lives and consciousnesses, of how they were described and evaluated by an observant Jewish contemporary.

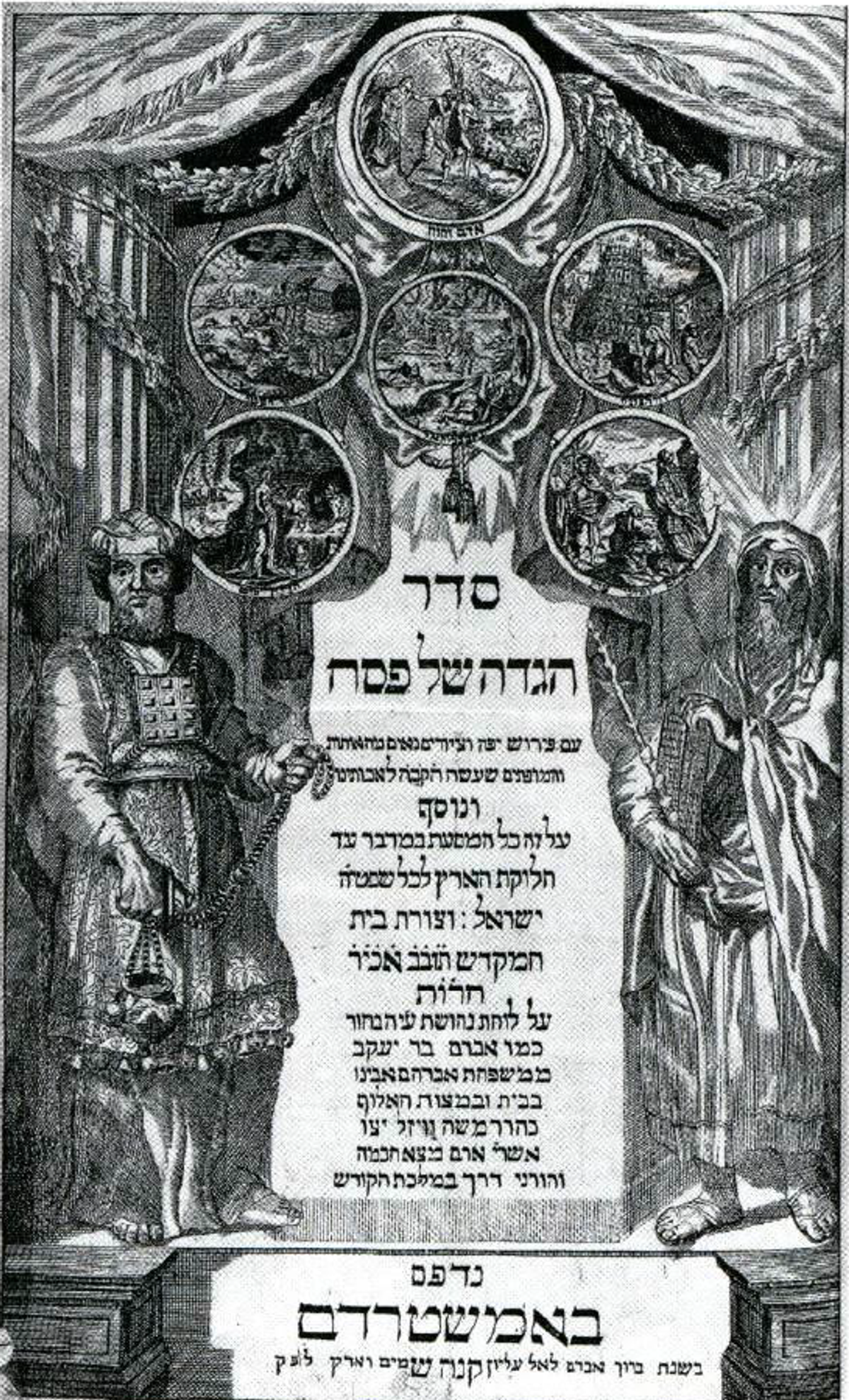

The classic portrait of the Court Jew owes much to the pioneering work of Selma Stern, whose broad contextualization of Jewish history and careful archival research place her within one of the strong historiographical traditions to emerge from the Weimar Republic. Stern explored the socioeconomic connections between the developing Prussian state and the Jews just as her distinguished and younger fellow émigré Hans Rosenberg explored them between Prussian bureaucratic autocracy and the Junkers. Stern described the range of activities—from provisioning armies to financing imperial elections—from which the category of Court Jew could be constructed and showed the link between these services and mercantilist absolutism of princely regimes in the 17th and 18th centuries. Her Court Jew was held in high esteem by the Jewish communities of Europe, using his wealth and influence to protect them and to further Jewish learning and publishing. The fall of Court Jews she blamed primarily on Christians: on those rulers who, having made use of them as financiers, reneged on their debts to vulnerable Jews, and on “forces” hostile to state-building, who turned anti-Jewish hatred against the princes’ servants.

In several ways, Glikl supports and illustrates such a view, as in her admiring wonder at Jost Liebmann’s wealth. In other ways, her text suggests a modification of the classic image. First, the Court Jews overlapped with other Jews in their practices and in the ways in which they were perceived; they were not a wholly distinctive type. Second, Court Jews sometimes were seen by other children of Israel as a source of peril, not just of patronage and protection.

Glikl’s own family did not start out with such elevated status. Her father, Judah Joseph Leib, had been one of the first German Jewish settlers in the thriving port city of Hamburg in the 1630s–40s. In contrast with Portuguese Jews, who had a formal agreement with the Hamburg senate, the hochdeutsche Juden were in the city on sufferance until the end of the century. Born in 1646–47, Glikl remembered a childhood moving between Hamburg and nearby Altona, where German Jews were under the more reliable protection of the Danish king. With the help of his wife, Beila Melrich, Judah Leib prospered in his trade, going to fairs and making loans not to princes but to local officers, merchants, and other city folk. Hayyim ben Joseph, Glikl’s husband, came from a similar background; his father, Joseph Goldschmidt, carrying on his trade from the smaller towns of Hameln, Hildesheim, and Hannover.

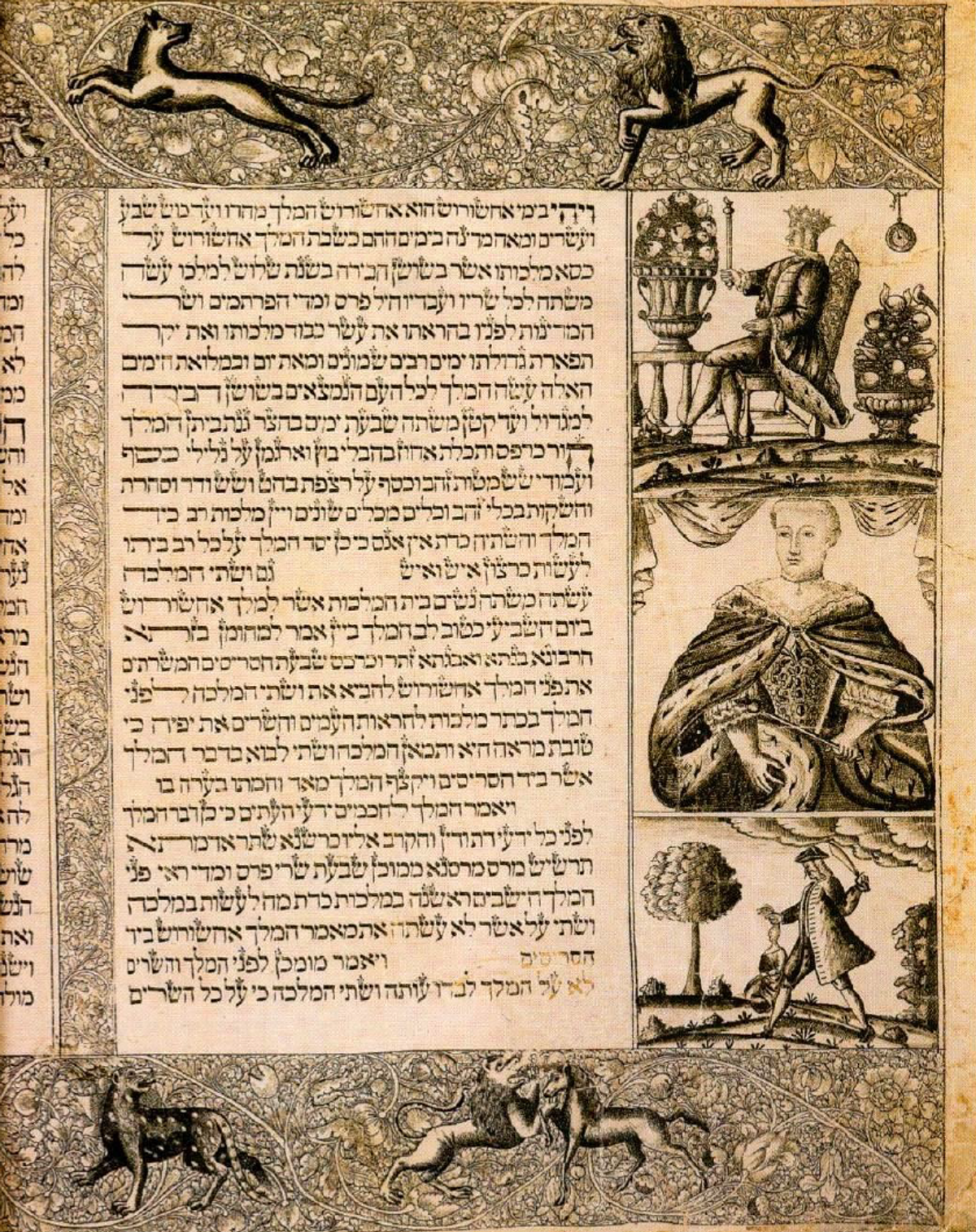

Glikl and Hayyim began young as a couple, marrying in their early teens as was the custom among the better-off Jews in the German states and Poland. For the 30 years of their marriage, they managed their business together, sometimes with partners and agents. Hayyim went to the fairs of Leipzig and Frankfurt and traveled to Amsterdam and elsewhere; Glikl stayed in Hamburg, taking care of the books, drawing up contracts, and watching over pledges while giving birth to 14 children. When they began, Glikl recalled, she and Hayyim could command little credit. At age 16, Hayyim was running around Hamburg buying and selling gold. By the time of his death in 1689, he was one of the most prosperous of the German Jews in the city, his trade centering on jewelry and pearls and reaching as far east as Moscow and as far west as London.

But Hayyim Hamel (also known as Hayyim Goldschmidt) did not himself become a financial agent for or provider to a prince. The closest he came was during his partnership with Moses Helmstedt of Stettin in Pomerania around 1679. Helmstedt, also known as Moses Levi Lipschutz from Helmstedt, had been among the first Jews to settle in Berlin after the Great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm had opened the city to them in 1670. Despite debts in Berlin, he somehow acquired the monopoly of the mint at Stettin, a Hanseatic port then under the jurisdiction of Sweden. Part of a generation of Jewish masters of the mint in central Europe, Moses Levi immediately began to tap his networks for a supply of silver. He turned to Hayyim ben Joseph, whom he knew perhaps through Berlin contacts or through the Leipzig fairs. If Hayyim would send him silver, Moses promised him a share both in the mint and in the pearl and jewel trade carried on in Stettin.

Glikl’s description of this partnership shows how she and her husband viewed business with governments at this stage of their lives. On the one hand, Stettin seemed full of possibilities. Jews were only now being allowed to reside in the city; Moses had good letters of protection, and “the whole land was open to him.” Hayyim calculated that the drittels minted in Stettin—one third of the standard coin of account, the Reichstaler—could be profitably exchanged on the Hamburg Borse for the drittels of Lüneberg and Brandenburg. Hayyim and Glikl went into the venture, sending their 15-year-old son, Nathan, to Stettin and getting a good return both on the coins they exchanged on the Borse and on the pearls they received from the Stettin trade. Moses appeared to be prospering: “[He] had a grand carriage with two of the best horses in Stettin, two or three man and maid servants, and lived like a prince.”

On the other hand, Hayyim and Glikl always worried about the reliability and honesty of their business partners—what Glikl called, in the language of both Jewish and Christian merchants of her day, their “honor.” Moses Levi had not told them about his Berlin debts when their partnership began. His princely style of living turned out to be, as it is elsewhere in Glikl’s writing, an ambiguous sign. He was spending well beyond the profits from the mint, and imprisoned during a trip to Berlin, he paid his debts with Hayyim Hamel’s money. Summoned by his son Nathan, Hayyim confronted Moses in Stettin. The latter swore by the Torah in the synagogue in his house that he would repay Hayyim, but his promises were worth nothing, and the partnership ended.

Royal agents and institutions enter into Glikl’s account of the mint venture twice. First, when Moses accused a government commissioner of a 1,000 Reichstaler error and then sued him at great cost before the court of Stettin—an action Glikl considered folly. Second, when Hayyim decided against suing Moses for payment before the same tribunal, not because it was bad form for Jews to prosecute each other in Christian courts, but because “Sweden is a bad place.” Glikl’s story did not here stress the vulnerability of Jewish minters to the whim of the prince or the vagaries of government policy, but only expressed a general suspicion of the fairness of Christian courts.

At least one Jewish family in Hamburg would have characterized Sweden as more than a “bad place.” The marrano Diego Teixeira had come to Hamburg from Antwerp not long before Glikl’s birth and had astonished the Christian world in 1647 by announcing that henceforth he and his would live as Jews. He took the name of Abraham and, together with his son Manuel/Isaac, became head of the most profitable banking business among the Portuguese Jews of Hamburg. Political finance was part of their fortune. Spanish payments to Denmark and Sweden passed through their hands, and they became bankers for Queen Christina of Sweden. Christina stayed in the splendid Teixeira house during at least two of her visits to Hamburg: in 1654, when she and Abraham made arrangements for him to administer all the properties granted her abdication, and again in 1661, when she made Isaac her “resident,” or representative, in Hamburg. In 1669–70, Isaac turned to her for assistance in his unsuccessful attempt to dissuade Emperor Leopold I from expelling the Jews from Vienna unless they converted.

Glikl bas Judah Leib said rather little about the Portuguese Jews of Hamburg in her memoirs. She described them as protectors of the German Jews in times of trouble and as fellow rejoicers, dressed in green, when news of the claimed messiah Sabbatai Zevi came to Hamburg. Hayyim ben Joseph had a business connection with a Sephardic merchant and lost money when his debtor went bankrupt. Glikl spoke of the skilled Sephardic physicians who tried in vain to save Hayyim after his fatal accident in January 1689. As for the Teixeiras, she mentioned them not in connection with commerce and power, but as a sign of their high social esteem in Hamburg. To cheer his wife up and get her to eat during a particularly trying pregnancy, Hayyim ordered from the Teixeiras’ cook a surprise meal “fit for the table of kings.” The cook for Queen Christiana would make meal for Glikl bas Judah Leib.

After Hayyim’s death in 1689, Glikl took over the business herself. She set up a hosiery manufactory and sold its products, Holland goods, and other wares in her Hamburg shop. She bought seed pearls and precious stones from Jews near and far and, accompanied by Nathan or another male relative, sold them at the fairs of Leipzig and Braunschweig and beyond. She borrowed and lent money on the Hamburg Borse, made loans to local people, Jews and non—Jews, and exchanged letters of credit across Central Europe. She described herself at her height as being able to marshal immediately 20,000 Reichstaler of notes on the Hamburg exchange, of selling 5,000 or 6,000 Reichstaler of goods every month, of traveling to Vienna with jewelry for sale valued at 50,000 Reichstaler.

These are impressive amounts, if not in the Teixeira range. But Glikl bas Judah Leib never became a Court Jew. To be sure, her son Nathan had credit relations with Samuel Oppenheimer and his son Mendel, purveyors of munitions and provisions to the armies of the Holy Roman emperor. As with the Stettin mint master, we have here another example of how Court Jews depended on extensive financial networks in order to serve a prince. Glikl herself must also have exchanged letters of credit with such personages, but very few women became purveyors and lenders directly to princes and their armies. The same is true of Christian women: Frequent providers of small-scale loans and investors in governmental rents and bonds, they were not entrusted with the large responsibilities and risks of government finance in the early modern period.

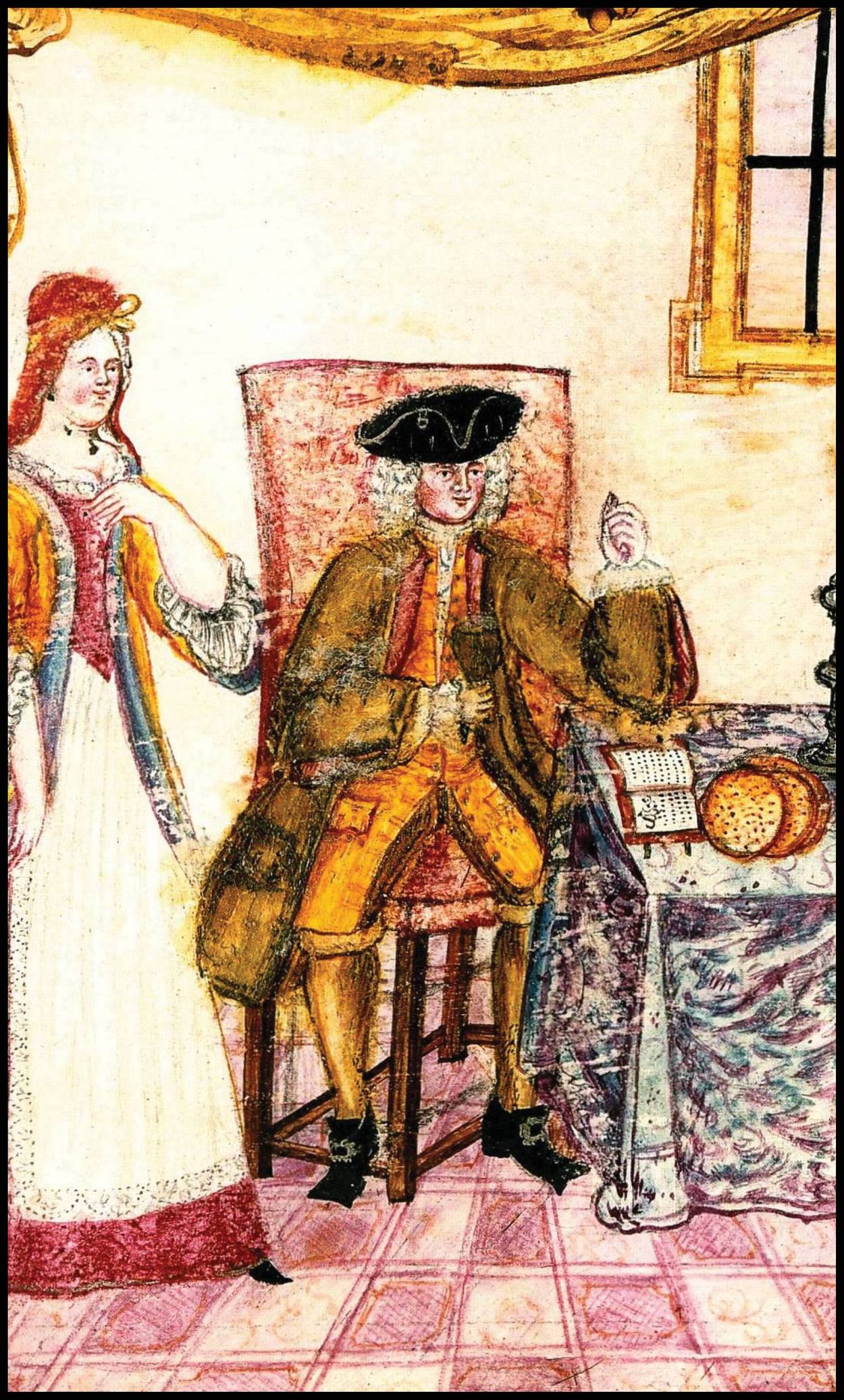

The exceptions in Glikl’s day show what was required for the unusual path: connection to a Court Jew through marriage and duties deemed appropriate for women. Cecilia, a widow of Michael Hinrichsen, continued her husband’s role as Court Jew in Mecklenburg after his death in 1710, especially supervising the state tobacco monopoly. Esther Schulhof from Prague was married to two Court Jews in Berlin, but it was only with her second husband, Judah Berlin alias Jost Liebmann, that she herself became a formal agent. Whereas her first husband had been an army contractor and palace provisioner to the Great Elector, Jost Liebmann, dealt only in jewels. Here was a trade Esther knew so well that she was maintained as Court Jew to Friedrich I after Jost’s death.

If Hayyim Hamel’s life had been different, Glikl bas Judah Leib might have taken her expertise in precious stones into a princely setting. As it was, her female commercial competence must have prepared Judah Berlin/Jost Liebmann for his later marriage to Esther Schulhof. Judah had started his business career as Danzig agent, then as partner, of Hayyim Hamel. The partnership ended bitterly after a year, but not before Judah had had the chance to see Glikl in action, advising her husband and favoring their enterprise together. Ultimately, peace was made between Judah Berlin, Hayyim, and Glikl—Judah had taken Hayyim’s niece as his first wife—and Glikl was to be in touch with the Court Jew and his second wife in Berlin during the 1690s.

Court Jews come into Glikl’s account as often in terms of family alliance and visits as in terms of mint ventures and loans. In her own generation, Hayyim’s sister Yenta took as her second husband Lipman Cohen alias Leffmann Behrens, treasurer and fundraiser for the dukes of Hanover and an important fiscal agent for ducal politics in the empire. Of the 12 children of Hayyim and Glikl who lived to young adulthood, Zipporah married the son of Elias Gomperz of Cleves, banker and military provisioner to the Great Elector of Brandenbug; Zanvil married the niece of Rabbi Samson Wertheimer, banker and financial adviser to the emperor; and Moses married the daughter of Solomon Samson of Baiersdorft, factor to the margrave of Bayreuth. If the mails had not been two weeks late with a dowry deposit, Glikl’s oldest son, Nathan, would have been betrothed to the daughter of Samuel Oppenheimer, the other court banker in Vienna.

What emerges from Glikl’s text is a network of European Jewish families of somewhat differing wealth, status, and power, but linked by marriage, credit arrangements, and information flow. What kind of figure was the Court Jew for Glikl in this group? Let us concentrate here on the first five books of her autobiography—that is, on what she wrote in 1689 and the 1690s as she looked back on her first marriage and her current years of widowhood.

The words Court Jew—hoyf yud—appear once in her text as a description of Solomon Samson of Bairersdorf late in the 1690s: he could not be present for the signing of his daughter’s marriage contract with Glikl’s son because he was “at Bayreuth with his highness the margrave, may his glory be enhanced, with whom he is very influential and whose Court Jew he is, as everyone knows.” In the quotation that opens this essay, Judah Berlin is esteemed by and does business for the elector of Brandenburg. These are the only places where Glikl made explicit the political role of a Court Jew. With Leffman Behrens/Lipman Cohen, the reader would assume he had some political weight, because Glikl turned to him to obtain a safe conduct in Hannover for her son Leib when he was being pursued by Berlin creditors. But she did not describe Behren’s projects for the dukes, even though Hayyim’s parents had lived with Yenta and Lipman in their last years, and Hayyim and Glikl had visited them there. With Elias Gomperz of Cleves, the reader would assume political connections with Friedrich Wilhelm, the Great Elector of Brandenburg, because he and the young prince Friedrich came to the wedding of Elias’ son with Glikl’s daughter. Glikl told how Elias regretted not presenting Friedrich with a gold and diamond watch because the son succeeded the father only a few years later, but she did not go on to talk of Elias’ activities as banker for the Brandenburg house.

In short, the princely connections of these elite Jews, economic and political, were important for Glikl, but they did not necessarily constitute a central distinguishing mark for them as individuals. She did not apply a clearly enunciated concept of Court Jew to all the different men and women who provisioned princes. After all, these people had other business interests as well, and their credit relations interlaced them with Jews like herself. Why should she draw a sharp line between them?

Court Jews shared certain qualities in her mental universe, however. One was their riches: oysher or kostin or reykh, wrote Glikl almost every time she mentioned their names. Such adjectives were not reserved for Court Jews—Nathan’s father-in-law, who replaced the Viennese Oppenheimer when the dowry was late, was also “wealthy”—but they were among the most affluent people she knew. When word got out among the Amsterdam Jews that Hayyim Hamel, still early in his business career, was about to contract marriage for his first child with the son of the “very rich [Elias Gomperz], a man worth 100,000 Reichstaler or more,” many could not believe it. They began to take bets on the Amsterdam Exchange about whether the deal would be made. But, as Glikl concluded, “what God resolves must come to pass.”

The houses of Court Jews, when Glikl described them, were “like those of princes.” Elias Gomperz’s house in Cleves was “really like the dwelling of a king, furnished like the mansion of a ruler.” Their lavish hospitality bestowed great honor of their guests and reflected honor on themselves. For the wedding of Zipporah and Kossman, Gomperz and his wife provided the finest of delicacies, foreign wines, and rare fruits. Served in a great hall with walls of gilded leather, the meal was followed by masked dancers, who performed all kinds of “farces and jokes” and ended with a Dance of Death (presumably in a comic rather than a somber mode). All this, together with the presence of the Great Elector and Prince Maurice of Nassau: “[No] Jew has had such honor for a hundred years.” Similarly, when Glikl went to Berlin for the wedding of her son Leib, Judah Berlin and Esther Schulhof sent her the most remarkable sweetmeats and jellies for Sabbath gifts and gave her a great feast, “honor beyond my worth.”

But Court Jews did not just stand for wealth and bestow honor. They could bring trouble too, as Hayyim learned from his partnership with the Stettin mint master Moses Levi. In the late 1690s, Glikl’s son Nathan abruptly had all his credit thrown into doubt when Samuel Oppenheimer and his son failed to make payment from Vienna on several large bills for which Nathan was correspondent. As Glikl told it, the news then reached Hamburg that Samuel and his son had been imprisoned. All of Nathan’s creditors descended on him demanding payment not only of Oppenheimer’s bills, but of others that he owed. Nathan honored as many of them as he could, pawned all his gold and silver objects, and left for the Leipzig Fair begging his mother to take care of whatever she could of his remaining debts. Glikl came through, pawning all of her own goods to do so, but found that her credit was suffering on the Hamburg Borse. Worried about the possibility of ruin, Glikl left for the Leipzig Fair, planning to go on to Vienna and see Samson Wertheimer if the Oppenheimers still had not paid. To her relief, she got word that father and son had been released from prison and that Nathan received funds for all his bills. Glikl concluded, “In such a previous plight … God, may His name be praised, saved us in an instant … Though the rich people concerned repaid our expenses, still they could never in all their days repay the fear, troubles, and worries we suffered through them.”

In this account, Glikl laid the blame squarely on the Oppenheimers. She quoted her son to the same effect along the way—the Oppenheimers “will not desert us”—as if everything was in their hands. In fact the financial difficulties of Samuel and Emanuel Oppenheimer had been occasioned by the efforts of the imperial minister of finance in 1697 to replace Court Jews with Christian army suppliers. Contracts were canceled, and then father and son were arrested on the basis of a false accusation that they had planned an assassination of their partner Samson Wertheimer and that Samuel hoped to become minister of finance himself. The plot to unseat the Oppenheimers failed. So great was the emperor’s need for credit for his current military ventures that the men were released.

Perhaps Glikl was not fully informed about the background to the Oppenheimer crisis at the time she recorded the story; perhaps she was reluctant to elaborate on imperial politics and “the concerned rich people” in this family manuscript. Whatever the case, her text reveals a state of mind. Jews involved in major affairs could bring danger to those who trusted them; they could not always be counted on.

Only God could be counted on. Running through Glikl’s autobiography is a dialogue about God’s intentions for the world and the relation between His plans, human agency, and actual events. The rise and potential fall of Court Jews was one of the cases in which she debated this relationship. Hayyim and Glikl had taken on Judah Berlin as their agent after their previous factor, Mordecai, had been murdered on the highway. “If God had let [Mordecai] live, perhaps Judah Berlin ... would never have come into his riches.” Glikl and Hayyim found young Judah “very learned, clever, and good at talking about business,” but when he went off to Danzig for them the first time, he owned no more than 20 or 30 Reichstaler worth of amber. “So, my beloved children, you see how when the true God wants to help, he can make much out of little. From such a small amount of capital has Reb Judah come to great riches and become a great man.” Of course Glikl also took some credit for herself and Hayyim: Even though the partnership ended in a ferocious quarrel, they were the ones who got Judah started.

Court Jews rose, and Glikl knew they could fall. In her explanation of why Solomon Samson of Baiersdorf had to delay the wedding of his daughter to Glikl’s son Moses, she finally moved into politics. Samson wanted to build a new house so as to give a splendid wedding for his youngest child, but especially:

The Margrave of Bayreuth had taken on a new counsellor, who opposed my rich relation Samson and—like another Haman—intended to destroy, blot out, and murder him. In truth, [Samson] was in a very sorry situation and did not know which way to turn, for everything he had was in the hands of the Margrave, may his glory be enhanced ... But the Lord, may he be praised, saw what great good came from [Samson’s] house, especially his hospitality toward the rich and the poor, and what good things he did for the Children of Israel in the margravate—he really supported the whole region—and would continue to do in the future. In his mercy and pity, the Lord, may he be praised, turned the wicked thoughts of this vicious Haman to good. The evil one was brought low and my relative is every day higher. It is impossible to describe how much importance he, a Jew, has in the eyes of the prince, may his glory be enhanced. May God maintain him thus till the coming of the Messiah.

The story had a happy ending and represents Glikl’s most fully developed attitude toward the Court Jew: pride in her in-law’s wealth and in the esteem in which he was held by the prince; pride in his charity and hospitality toward his fellow Jews; recognition of his vulnerability. Her young adulthood had been marred by the disappointment of the lost Messiah. Thinking of Solomon’s good fortune made her hopeful for a moment once again.

Was Glikl bas Judah Leib really as worldly as these quotations suggest? Were riches and social reputation all that mattered? Were the loss of money and betrayal of commercial trust the supreme injuries?

By no means. Glikl’s autobiography is filled with sorrows. The most important in the first five books are the loss of her 3-year-old daughter, Mattie, and the death of her husband, Hayyim. These much outweighed temporary losses in the Stettin mint or in the short-lived Judah Berlin partnership. Throughout her text, Glikl bas Judah Leib tried to quiet her soul and accept whatever God sent. She did so by moralizing and especially by storytelling—that is, by interspersing her life story with folktales.

“Who knows if it is good to have riches ... and spend our time in this transient world in nothing but pleasure?” Glikl asked already in her first book. Drawing from a Yiddish source, she told the story of the visit of Alexander the Great to the wise men of the East. They lived in great simplicity, not caring for things of the world. When Alexander wanted to give them costly gifts, they refused, saying, “We need no money or silver or gold; nature provides us enough.” When the king said proudly that they should then ask of him what they wanted and he would give it, they answered with one voice, “Give us eternal life.”

In her fourth book, much of it devoted to commercial affairs like the Stettin mint, Glikl recounted the ups and downs in the life of her sister Rebecca and Rebecca’s husband, Samuel Bonn. Twice they became wealthy and then lost everything. After asking God to have mercy on all Jews who had fallen on poverty, Glikl recounted the story of Solon and Croesus.

Her version, taken from a Yiddish or German source, has several differences in detail from Herodotus’ original, but the central line is there. King Croesus asks the philosopher Solon if he is not fortunate in all his riches and honor. Solon warns him that no one can know if he is fortunate till he sees how his life turns out. He tells of an Athenian citizen who lived to see his 10 children serve their country faithfully and died knowing he and they were esteemed (in Herodotus’ version, the progeny die in battle). Croesus is offended at Solon’s comparing him to a mere citizen and sends him from his court. Years later, the king is taken prisoner in war and, as he is about to be executed, cries aloud as he recalls Solon’s warning. His captor asks what he has said and, learning of Solon’s prediction, thinks, “Croesus was once a great king, and God has put him in my hands. Who knows? I have not reached the end of my life, the same thing may happen to me.” So he lets Croesus live and return to his land. “We do not know what our end will be,” Glikl concluded.

And, indeed, she did not know, as she wrote those words, how her own life would end. The tale was good preparation for her second marriage in 1700 to Hirsch Levy, also known as Cerf Levy, a leading banker of Metz just inside the kingdom of France and a shtadlan (intercessor) of the sizable Jewish community there. The business relations of the wealthier Jews of Metz with the royal government were a variant on those in the German states. A formal office of Court Jew would have been unacceptable for His Very Catholic Majesty, who had just expelled the French Huguenots and was fighting Jansenist heresy. In principle, Jews were not allowed even to visit in the city of Paris. In fact Colbert had insisted on the economic usefulness of the marranos in Bordeaux, and the war minister Louvois was happy to make use of the Jews in a garrison town like Metz to provision his new military depots. The royal intendant for the Metz region would meet with now one, now another group of Jews—sometimes with all the leading men of the synagogue—to make deals for horses, grain, tents, and funds for the army’s wages. Thus, during the famine year of 1698, Hirsch Levy, together with his frequent partner Abraham Schwabe, alias Krumbach, brought grain from Germany to the local troops and to the city population. In the course of such negotiations, Jews won the privilege to go to Paris at least long enough to draw on their letters of exchange; Glikl’s son-in-law Moses Schwabe, alias Krumbach, was in Paris on such an errand when she first arrived in Metz.

As Glikl told what happened in her sixth and seventh books, she had received invitations to remarry during the 10 years of her widowhood “from the most distinguished men in the whole of Ashkenaz.” (Presumably, some of them were Court Jews; she did not give their names.) She had turned them down, preferring her independence, but in 1699, now in her early 50s, she began to weary of standing in her shop all day and running around to fairs. She also feared she might become less attentive to business matters and risk bankruptcy. When a letter came from her daughter Esther and son-in-law Moses in Metz proposing marriage with Hirsch Levy—“a widower, an outstanding Jew, a scholar, very rich, and maintaining a fine household”—she accepted. Closing all her accounts with Jews and non-Jews, she left Hamburg with Miriam, her last unmarried child, and moved to the city on the Moselle.

Her description of her reception in Metz and of Hirsch Levy’s household has the kind of superlatives she had used for Court Jews in her earlier books. “I saw more gold and silver in his house than I had seen in any wealthy man’s in all of Ashkenaz.” Indeed she felt a little intimidated by her stepdaughters’ disapproval of her modest Sabbath gifts and by the contrast between her “straightforward German ways” and the Frenchified politesse of the elite Jewish families of Metz. But she soon began to fit into the community, enjoying conversations with her daughter Esther and Esther’s mother-in-law, the esteemed Jachet bas Elias, wife of Abraham Schwabe.

Then, within two years, Hirsch Levy went bankrupt. According to Glikl’s recital and to archival sources, his downfall was not immediately connected with his occasional role as provisioner to Louis XIV’s troops. Glikl never even mentioned such ventures. The Jewish communal organization thought there may have been some “disorder” in Hirsch Levy’s affairs, but blamed his ruin especially on the greed of his Christian creditors, who had charged him excessive interest. Glikl too, after her initial anger had subsided, attributed the bankruptcy to overly impatient creditors (she did not distinguish between Jewish and non-Jewish ones) and insisted on Hirsch’s honesty and business acumen. Escaping arrest, Hirsch finally settled with all his creditors in the course of 1702.

Glikl bas Judah Leib was humiliated. It was not so much the loss of two-thirds of her dowry, not so much the straitened circumstances in which she and Hirsch had to live—in fact their children gave them considerable help. It was the particular dishonor of bankruptcy which troubled her, and the loss of prestige within the community. Her writing in the immediate wake of Hirsch’s fall stressed all the more strongly the uncertainty of human life and sureness of the Lord’s providence: “God, may His name be praised, laughed at my plans.”

Hirsch Levy lived on to counsel his son Samuel against an undertaking as a master of the mint. This episode provides a final example of Glikl’s commentary on the attractions and dangers of the status of the Court Jew. Samuel Levy had studied Talmud in Poland and had won much admiration for his learning. Returned to Metz, in 1700 he had been named head rabbi of Alsace, a post he filled energetically, trying to get his flock to live according to the law and to charge only reasonable interest for their loans. But he and his wife, Hendele Schwabe, were not content with his income. Both had grown up in grand households, surrounded by luxury and hospitality, and “a handful cannot satisfy a lion.”

Thus in 1708-09 Rabbi Samuel crossed over the border into adjacent Lorraine, opened a shop with two of his brothers-in-law, and found employment with the duke of Lorraine, whose court was then at Luneville. Samuel and his relatives were to provision the court with various goods and grain and, especially, take over the mint and supply it with silver. Moses Rothschild, also known as Moses Alcan, went to Lorraine as well, all of the families holding on to their houses back in Metz.

Hirsch Levy warned his son that the mint enterprise would come to no good, “that the king of France would not tolerate it.” Let us go beyond Glikl’s compressed references to coins circulating across borders to reconstruct Hirsch Levy’s concerns. He would have perceived both the political and the commercial tension between Louis XIV and Leopold, the brilliant young duke of Lorraine. Though Leopold had married Louis’ niece, the French king doubted his neutrality during the War of the Spanish Succession and had his troops occupy Nancy to make sure Lorraine did not favor the emperor. From a new capital at Luneville, Leopold was embarking on economic and fiscal reform, welcoming new immigrants and industries. He aligned his currency with that of the French and proceeded to do everything he could to attract French coins into his duchy and remint them as Lorraine coins. There ensued two currency wars: a mercantilist one between king and duke over control of the other’s coins; a speculative one among merchants—as it was called—selling coins for a higher price across the French border than they were worth in Lorraine (as, decades before, Hayyim had made a profit by selling Stettin drittels on the Hamburg Borse). As Lorraine minters with French connections and insider knowledge, Samuel Levy and his colleagues were implicated in both of these wars. A story was afloat that jealous Jewish competitors in Metz had denounced Levy and the others to the French authorities.

In 1712, so Glikl recorded it, Louis XIV ordered Samuel Levy and his partners to break with the Lorraine mint or never reenter the kingdom of France. The notice was read aloud in the synagogue of Metz so their names could be struck from the community register if they did not comply. The brothers-in-law went back to Metz with their families, but Samuel ben Hirsch and Hendele and their children stayed in Lorraine, as did Moses Rothschild. Hirsch never recovered from the blow and died soon after in July 1712.

Glikl did not moralize the episode any further. A few years after Hirsch’s death, she moved in with her daughter Esther and her son-in-law Moses Schwabe, now “the richest man in the Jewish community ... his doors open to the poor ... and to prominent visitors from the ends of the earth.” But she surely heard the last act in the drama of Samuel Levy, which fulfilled his father’s worst fears: his bankruptcy in 1717, the suit against him for fraud in 1718, and his expulsion from the duchy.

Samuel did well for a time after his decision to remain in Lorraine, prospering both in his own commercial ventures and in those for the duchy. In October 1715, Duke Leopold appointed him to the post of receveur général—that is, treasurer of Lorraine. Duke Leopold had built himself a “Lorraine Versailles” in Luneville. Samuel also built a new house for himself, “a palace” in the words of his Christian creditors, with fountains, furnishings of gold and silver, and a synagogue with precious objects and his own rabbis. He had many horses and carriages and more servants than on a prince’s staff. Anyone who entered his house was offered fine wines, coffee, tea, chocolate, and other delicacies. His wife’s clothing was said to be more splendid and varied than that worn in Paris; his children all had tutors and enormous dowries when they married.

Samuel’s troubles started not with the duke, but with high officers and nobles in Leopold’s entourage. The ducal palace and other luxuries had to be paid for by various expedients, such as a tax on ennobled families, the sale of offices, and an increased salt tax. A Jewish treasurer was a convenient target for discontent: The Chambre des Comptes refused to take an oath to a Jew, and his enemies accused him falsely of failing to pay the troops on time. In December 1716, after a year of this opposition, Duke Leopold removed Samuel as treasurer, even while attesting a few months later to how faithfully he had performed his duties and continuing to seek his counsel.

Then, in the spring of 1717, Samuel Levy declared bankruptcy. According to him, his losses were due to the usurious demands of his creditors, both Jewish and Christian, who had taken advantage of him. Pressed to borrow money for the duke, he had had to pay high interest rates—100% in some cases—and even to accept overvalued goods instead of cash. He had ended up with losses of more than 2 million livres.

According to his creditors, the losses were fabricated. First, Samuel’s Jewish creditors took action against him; then his Christian creditors had him, his wife, Hendele, and his two agents arrested in May 1717. They were released after all their goods had been seized and Levy had agreed to pay two-thirds of his debts. Rabbi Samuel had the nerve to have a Yom Kippur celebration at his house, the noise of which could be heard all over town. The following spring, with only an eighth of his debts paid, he was imprisoned again and accused of concealing his assets and of fraudulent bankruptcy. His Christian creditors threw in the extra charge that he gave more favorable terms to Jewish traders than to non-Jewish ones. In late 1721, a panel of arbitrators set up by the duke determined the additional amounts that Samuel had to pay. He was finally released after almost four years in prison, only to discover that Leopold had ordered the expulsion from Lorraine of all Jewish households that had come to the duchy after 1680.

The anti-Jewish suspicion of a Jewish ducal treasurer is, as we have seen, an expected feature of the historical portrait of the Court Jew. It is the other part of the story which gives pause and returns us to the question of how evidence from Glikl bas Judah Leib adds to our understanding. One of the legal briefs for the creditors of Samuel Levy tried to explain what had gone wrong with him. His business practice and credit had been honorable and responsible until he had sought an appointment as treasurer of Lorraine. Then he had come to desire “all the wealth of China” and had become involved in perilous ventures at huge rates of interest.

Could there be something true about the interpretation that the role of the Court Jew was hazardous not merely because a ruler could renounce his debts and use anti-Jewish feelings to get away with it but also because it put an added strain on the relations of credit among Jewish bankers and traders? After all, Samuel Levy’s Jewish creditors, some of them his kin, sued him over the years just as his Christian ones did. Jewish business relations were always somewhat turbulent—the quarrel between Hayyim Hamel and Judah Berlin was not unusual—but the basic European structure worked because it was founded on trust and information flow across a wide expanse and many boundaries. Intendant Turgot had told Louis XIV that the Jews of Metz performed well as traders because they constituted “a kind of republic and neutral nation for commerce among different states.” Did the role of Court Jew not only give support to that republic by patronage but also disrupt it by concentrations of overweening power?

“Riches and Dangers: Glikl bas Judah Leib on Court Jews” is excerpted from From Court Jews to the Rothschilds: Art, Patronage, and Power, 1600–1800, edited by Richard I. Cohen and Vivian B. Mann, © 1996 Prestel-Verlag and the Jewish Museum, New York, published by the Jewish Museum and Prestel in conjunction with the 1996 exhibition, reprinted by permission.

Natalie Zemon Davis is a Canadian and American historian of the early modern period. She is currently a professor of history at the University of Toronto in Canada. She is the author of The Return of Martin Guerre, Women on the Margins, and Trickster Travels, among many others.