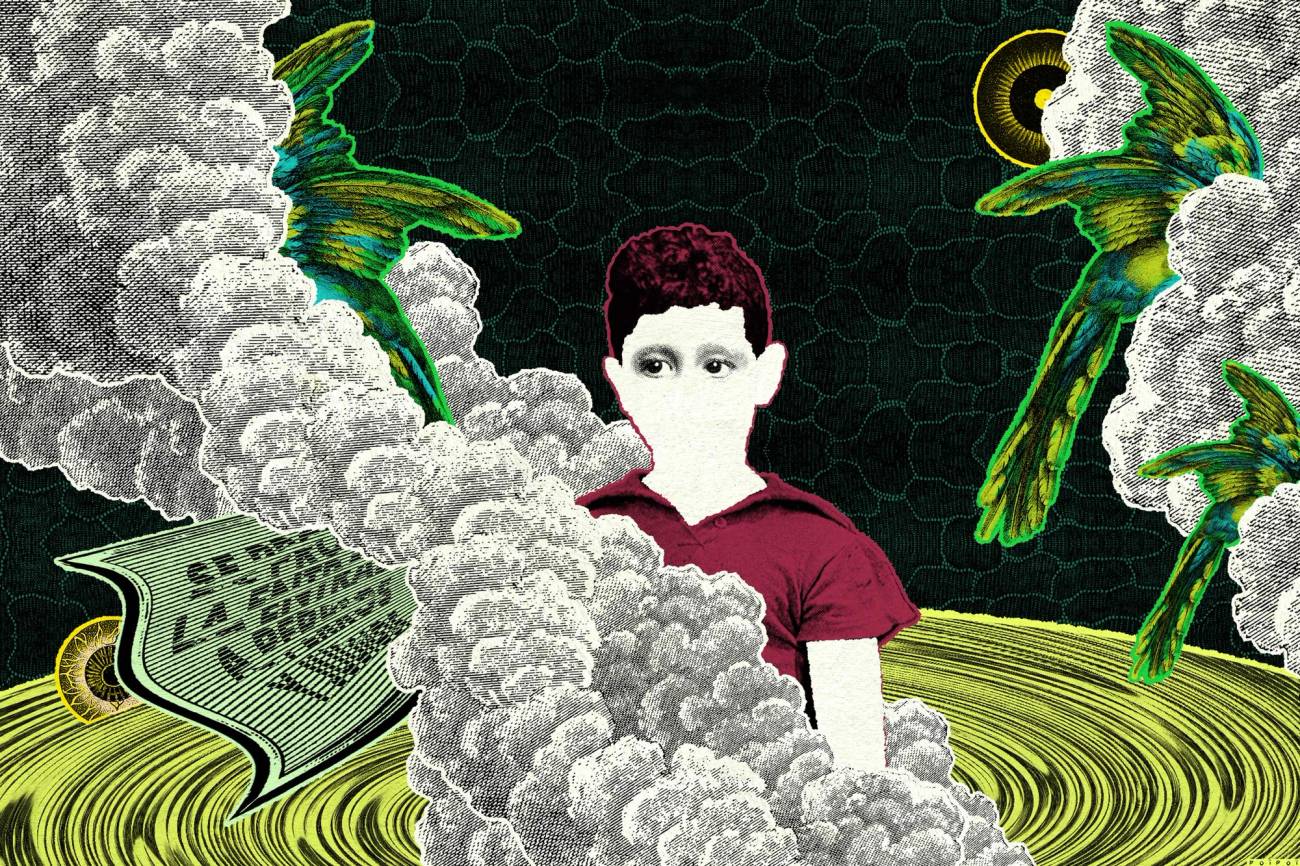

There was a kid in my third-grade class, in Guatemala, who flippantly called the few Jewish boys Israel, and the few Jewish girls Sara. To him, I was no longer Eduardo, but Israel.

Although I knew that his was an antisemitic taunt, I was still too young to fully grasp its meaning. It took me years to understand that the boy had copied it from the Germans (and probably, as I’d later find out, learned it from his father or grandfather). Specifically, that this very practice had been a law in Nazi Germany: the second article of the Law on the Alteration of Family and Personal Names, established in 1938, which officially gave the name Israel to any Jewish man with a non-Jewish first name (there was, of course, an authorized list), and officially gave the name Sara to any Jewish woman with a non-Jewish first name.

Israel and Sara. An entire people reduced to two names.

The boy’s name was Franz Peter. Or maybe it was Peter Franz. Be that as it may, he was much taller and stouter than me, and had hair so white and skin so fair that sometimes, in the sun, he gave the impression of suffering from albinism. We lived in the same neighborhood of Guatemala City, rode the same bus to and from school. One afternoon, sometime in the late 1970s, we met by chance out on the street, both of us on our bikes, and Franz asked me if I wanted to come see his magazine collection. We arrived at his house in no time at all (I’d been there only once before, invited to one of his birthday parties, at the end of which all of us kids received a live chick as a parting gift). We left our bikes lying on the front lawn and went inside. But as soon as I started climbing the wide ostentatious staircase and saw the antique silver and wooden crucifix hanging on the wall, I felt like an intruder.

Franz locked his bedroom door. He got down on his knees, reached under the mattress, and pulled out an old beekeeper’s suit; I don’t remember how he got it, or maybe he never told me (it was possibly stolen). Then, with his head already tucked inside the white veil, he reached under the mattress again and pulled out a flimsy cardboard box and started showing me magazines. Almost all of them were about soccer, though there were also two or three comic books and a more scientific publication with pictures of naked women from some Amazonian tribe. But suddenly Franz put his hand inside the cardboard box and reached for a thinner, smaller magazine, perhaps half-letter size, with a cream-colored cover and black lettering and with the other pages rustically tied together using a string of yarn, and he began talking to me about the pamphlet he was holding like a treasure in his hands. From the tone of his voice, now sharper and more excited, I understood that that old and well-hidden pamphlet was the main reason why he’d invited me to his house. Franz, still disguised as a beekeeper, kept talking to me—he was now saying something about his grandfather and his father—and I was still trying to decipher the image on the cover. In the center, there was one word composed of three thick black letters placed in the middle of an imperfect, trapezoidlike square with an equally thick black border. But the word made no sense to me. Pax, it seemed to say, though not quite. It took me a few seconds to finally understand that one of the letters—the third one—was not a letter but a symbol, and that at the bottom of the cover, just below the black and imperfect square, there was a single short phrase in smaller capital letters.

Paz se escribe con swastika, it said in Spanish. Peace is written with a swastika.

I had forgotten that pamphlet, and I had also forgotten that afternoon at the home of the beekeeper Franz Peter or Peter Franz—until a few years ago.

While in New Orleans, a professor from Tulane University invited me to visit the Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, whose fourth floor houses an extensive collection of Latin American books and historical documents. After a couple of hours of purposeless prying around, happily lost among the stacks and cabinets, we found a bundle of magazines and documents published in Guatemala in 1939 by the Official Information Service of the German Legion. And there, in that bundle, I again saw the same pamphlet barely held together with yarn. The same black swastika instead of the Z.

A Spanish journalist once asked me to name him the unread books that had influenced me most as a writer. What were the books that I had never read, the Spanish journalist asked me again, so as to be clear, which had influenced me most as a writer? A ludicrous question, I thought, but I then thought it was also a brilliant question. And sitting in front of the Spanish journalist, I immediately knew my answer: the Torah and the Popol Vuh. I’ve never read either of them, but there are no two books that, as a man and as a writer, have influenced me more.

When I mentioned to a friend this bizarre question-and-answer exchange with the Spanish journalist, she asked me why I didn’t just read both books now? Why did I still doggedly insist on not reading them? And I told her, with as much gravitas as I could muster, that if I did read them now I’d undoubtedly explode.

The truth, however, is that I don’t feel I need to. I already carry both of them with me, written somewhere inside me. The book of the Jews and the book of the Guatemalans, if I’m allowed that oversimplification, and if I can call books those two monumental works that represent and define my two worlds—the two great columns upon which my house is built. But a house that for some reason, ever since childhood, I needed to destroy or at least abandon. I can’t explain why I always felt that way, as if something was forcing me to run off and disappear.

I’ve spent an entire lifetime running away from home.

My father parked his fire-red Datsun 280 under a huge and lonely palm tree lost in the middle of a parking lot somewhere in Guatemala City. My brother, desperate in the cramped back seat, kept rushing me and kicking me from behind, and so I opened the door and got out of the car.

It was Sunday, still very early in the morning. My father was already standing behind the Datsun, taking his things out of the trunk. He said something to my brother and me as he closed it and the three of us started walking silently toward the entrance, my brother on one side of my father and I on the other.

The only sounds at that hour of the morning were the shrieking din of a flock of parakeets up in the palm tree and the clinking of my father’s clubs in the golf bag and the metallic scraping of his cleats on the dry pebbles. Without realizing it, I started walking faster, if not running, but my father shouted at me from behind and so I had to stop and wait for them. I was too excited. It was my first time there. It was the first time my father had brought us with him. The three of us continued walking together and it took us what seemed like an eternity to cross the parking lot. But in the final stretch toward the front door of the clubhouse, already on a narrow asphalt path, it was my father who now accelerated his steps (or at least that’s how I remember it, as if he was escaping from something or rather escaping toward something). I had remained behind them, alone, still on the asphalt path, my gaze downward. My father ordered me too firmly to hurry up, holding the door open and waiting for me to enter. My brother echoed my father, standing beside him. But I ignored them. I had only recently learned to read capital letters and I still stopped at any sign or lettering to practice. My father again shouted something at me, but I just kept trying to decipher the big black letters on the white background of a sign driven into the grass just off the asphalt path, until I finally managed to read the full sentence.

Se prohíbe la entrada a perros y judíos.

No Dogs or Jews Allowed.

I turned to my father, asking for help, but he just told me it was nothing and grabbed my hand awkwardly and pulled me tight and the three of us entered where we were not allowed to enter.

Today I find it hard to believe that I ever really saw that sign.

I know that I was shown the hidden swastika in the privacy of the bedroom of Franz the beekeeper, who openly and not-so-jokingly called me Israel. But it’s difficult for me to accept, albeit naïvely, that such an antisemitic sign could still be displayed in public in the Guatemala of the late 1970s. It occurs to me that maybe I never saw it that one Sunday morning with my father and brother and I only have the image of the sign created in my imagination from my father’s telling me of it, from my father’s voice? Maybe it was he, an avid golfer, who described it to me and thus left it tucked away in the secret vault of my memory? I recently mentioned the sign to my father, and he replied almost angrily that he didn’t remember anything. He didn’t remember going with us to the golf club on a Sunday morning, and he didn’t remember telling me about the sign, and he didn’t remember there even being a sign in the golf club’s front lawn.

Do I remember it better than my father, then? Or did my childish imagination invent an entire scene—complete with a fire-red sports car and the metallic sound of cleats on stony pebbles and the hysterical screams of a flock of parakeets—from the mere idea of a sign? Had that sign just existed in my mind? Is the imagination so bold and capricious that it can invent a memory and then turn it into something we perceive as real? In any case, it doesn’t much matter. The sign existed. I saw it or I imagined it, which for a child is the same thing.

I can still see me standing there that Sunday morning and reading the black, all-caps sentence written on the sign and immediately understanding that for the members of that club, and for some if not all of my fellow Guatemalans, there was no difference between me and a dog.

I must have been 6 or 7 years old when I found out that the sign existed, either because I saw it along with my father and brother on a cold Sunday morning, or because my father described it to me one day that he now no longer remembers. And since then I’ve never been able to forget it. Not so much due to the sign itself, but to the feeling of rupture that it left inside me. From that moment on—from that one black, hateful sentence—my two worlds became forever separated, and I was outcast from both of them.

Eduardo Halfon is a Guatemalan writer.