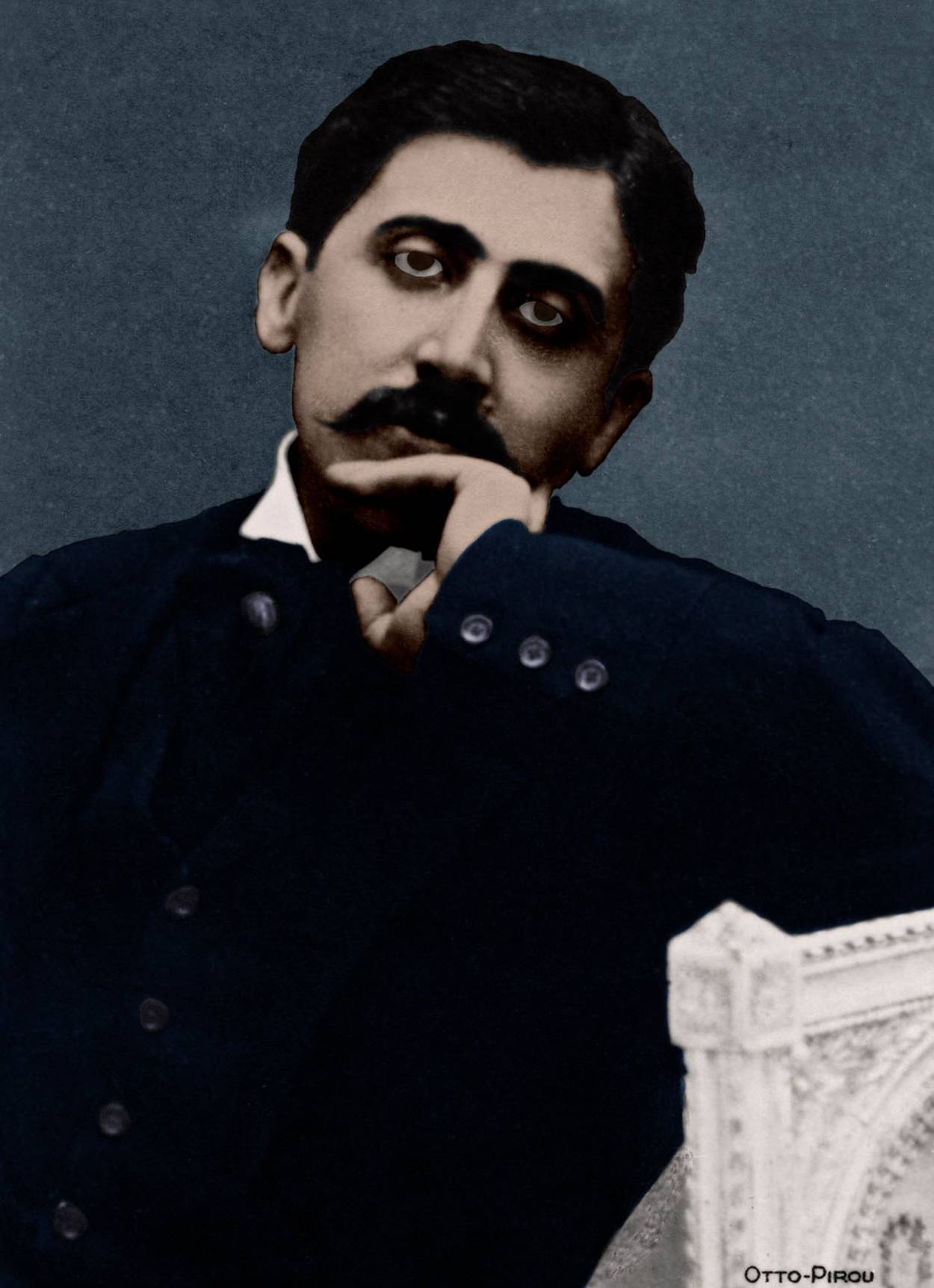

In 1949 Marcel Proust’s niece, Suzy Mante-Proust, gave the publisher Bernard de Fallois some papers her uncle had left to her father, the author’s younger brother, Robert. She asked him to give the papers some form of order. Fallois was able to assemble two posthumous books, Jean Santeuil (1952), a very rough first attempt at a semi-autobiographical novel, and, Contre Sainte-Beuve (1954), an assortment of essayistic and narrative texts, which Fallois called “the dream of a book, an idea of a book.”

In his preface to Contre Sainte-Beuve, Fallois also wrote of the existence of “soixante-quinze feuillets”—75 sheets—of manuscript text of Proust’s oldest version of À la recherche du temps perdu. But when a large number of manuscripts Marcel left to Robert were donated by Mante-Proust to the French National Library, these pages were not among them.

These missing pages, which experts called the holy grail of Proustianism, were thought to be lost forever. In 2018, after Fallois’ death, the 75 sheets—which turned out to be 76 sheets—were found in folders among Fallois’ effects. They had been grouped by theme and placed in five file folders inside a cardboard file bearing names given by Fallois: “Soirees de Combray,” “Le Coté de Villebon,” “Les Jeunes Filles,” “Noms nobles,” and “Venise.”

These pages, with their corrections, repetitions, and abrupt name changes, are the fount from which the thousands of pages of the final work flow. They are drafts, but they are drafts of genius, and in April they were published by Gallimard, the most prestigious of French publishing houses, which had rejected Swann’s Way when Proust submitted it to them in 1912.

Proust had abandoned fiction in 1899, when he set aside Jean Santeuil. His mother’s death in 1906 appeared to have sparked the urge to write fiction again, and in either late 1907 or early 1908 he again felt the desire—or was it the ability? —to write fiction. He would return to these newly published rough pages, revising and adding to them. Reading them now, we are present at the creation of the most profound, the most inexhaustible work of literature of the 20th century. If humanity were to disappear, all of its emotions, foibles, drives, and desires could be recreated from its pages.

In Fallois’ folders can be found in a preliminary form many of the elements and incidents that would be central to Proust’s completed masterwork. Here we have the narrator’s almost crazed desire for his mother’s goodnight kiss that takes up the opening section of Swann’s Way; the encounter with the young women, the jeunes filles en fleurs at a seaside resort of the second volume of the work, among whom will be the narrator’s great love, Albertine. Proust’s obsession with the romance of the great names of the French aristocracy is here, as is the heart of this entire undertaking—the idea of involuntary memory, the only true and valid form of remembrance, according to the author.

Most of these matters, as is natural in early drafts, differ from the final versions: the iconic madeleine in these pages is the far more prosaic toast. Sound, not just taste or the narrator’s position standing on cobblestones, is added to the battery of things that can revive the past. Proust writes here, after trying in vain to resuscitate a lost day of his youth, that “I let my spoon fall onto my plate. There was then produced exactly the same sound as that of the hammer of the brakemen who that day struck the wheels of the train at its stop. At that same moment the burning and blinded hour when this noise rang out was revived for me …” Perhaps most surprisingly, the Narrator, here given his actual name, has a younger brother, an annoying one to boot, who “though only five-and-a-half years-old, was of a rather violent nature.”

The style of these newly discovered pages is distinctly Proustian, and a sentence that traverses an entire page is not a rarity. There are also strikingly humorous pages, as when Marcel sets out to translate an elliptical, enigmatic letter written by his beloved but eccentric grandmother, who felt that “out of prudence one must never write proper names in letters, [and since] she spoke of everything through allusions, figures of speech, [and] enigmas, no one understood who she was talking about.” Her odd—for a French person—taste for fresh air and open windows inspires passages of endearing lightness, which are especially piquant when we remember that Proust kept himself in a cork-lined room to avoid asthma attacks.

In the final version of In Search of Lost Time, some of the characters have one main source in reality, but almost all are an amalgamation of many people in Proust’s life, with traits and characteristics even crossing from one gender to another. Albertine, the narrator’s love interest, for example, is based in part on a love of Proust’s, his chauffeur Alfred Agostinelli.

In the Seventy-five Pages, a small number of key characters maintain their real names. The narrator is called “Marcel,” his maternal grandmother is called “Adèle,” and his mother is called “Jeanne.” The final version will find the narrator nameless, his mother simply “Maman” or “ma mere,” and his grandmother, after several failed attempts at finding the right name for her, will become Bathilde. The characters’ actual names, which return us to their bearers, are a reminder of the great unspoken trait of the finished work: the Jewishness of one side of Marcel’s family.

The effacing of Marcel’s own Jewishness in the final Narrator is one of the most striking characteristics of Proust’s work, in which the Dreyfus affair, Jewishness, and Jewish characters feature prominently. Proust’s maternal grandmother’s maiden name was Berncastel, and her married name was the common Alsatian Jewish name, Weil. A great-uncle who appears here was actually Louis Weil—born Lazard Weil—the author’s grandmother’s brother-in-law. Weil was also Proust’s mother’s maiden name.

The de-Judaization of the Narrator was not the product of family resentment. To the contrary, Proust adored his mother above all people in the world, and his bemused affection for his Jewish grandmother is obvious. Proust’s Jewish relatives were financially successful and at first they are not all anonymous.

In one of the “autres manuscrits”—other manuscripts—included in the new volume, when the “miserliness” of Marcel’s great-grandmother, who refused to pay for her bus rides, comes up, we are told that she believed that the president of France exempted her from paying her bus fare thanks to her “relation to M. Cremieux” (she was his sister-in-law). The Cremieux in question was Adolphe Cremieux, the Jewish political figure responsible for the granting of French citizenship to the Jews of the then-French colony of Algeria in 1870, who was, in fact, married to an aunt of Proust’s grandmother.

Cremieux does not appear in the finished work, but his shadow lingers: In the final version the Narrator’s uncle—at whose flat he first sees the woman he will later know as Charles Swann’s wife, the cocotte Odette—is named Adolphe. This uncle, Marcel’s grandmother’s brother-in-law, with whom she has an edgy, teasing relationship in the manuscript pages, was well-connected and well-off, welcome in the finest homes. And yet, whenever he spent time in the countryside, he would ask Marcel’s family or those who invited him to their homes to arrange for him to meet with the daughter of a local country judge or a farmer’s daughter. Proust writes, “there was a certain boldness on my uncle’s part … in wanting everyone in the world to serve as his matchmaker.”

This affection for women of lower social status was later shared between the novel’s Uncle Adolphe and Charles Swann. A social explanation for this preference for approaching women he is “above” is given in a preliminary notebook, which demonstrates Proust’s sympathy for the lot of the Jew in French society: “Perhaps his Jewish origins were to an extent the cause for this … which gave him, from the memory of the humiliations it is rare a Jew did not feel in his childhood, a kind of fear of being scorned, of being looked on poorly.”

Proust’s Jewishness played a part in his public and private activities, in his friendships, and his family relations. But there was nothing straightforward about it in either case.

But Proust undercuts this sympathetic view by proposing another reason for Swann’s (and his uncle’s) taste for young French women of the popular classes: It was also his Jewish roots that, Proust suggests, “led him (in the way certain Romans found a greater charm in penetrating certain Oriental captives) to find a particularly great attraction in pious young Christian women, where his unbelieving soul drank with delight the new taste of the holy water and the earth of France.” This urge to besmirch and “penetrate” Christian women is an all too familiar antisemitic trope.

In the early versions included here, as in his life, Proust’s Jewishness played a part in his public and private activities, in his friendships, and his family relations. But there was nothing straightforward about it in either case. Through the magic of fiction and transmogrification of characters, Proust’s own Jewishness was disappeared by disappearing that of his relatives. For Nathalie Mauriac Dyer, Proust’s great-grandniece, who is the editor of this volume and the author of the remarkable analytical text that follows Proust’s manuscripts, the attribution of characteristics originally belonging to a member of Proust’s family to an outsider like Swann, was a way of “speaking of Jewishness without saying it is connected to his own family.” The fictional Marcel obliterated any trace of the Jewish half of his background, just as he treated homosexuality as a sexual preference that others engaged in. And yet the finished novel is a markedly Jewish book.

The early parts of In Search of Lost Time take place at the height of the Dreyfus affair, and even in the world of social snobbery in which the narrator spends his time, his companions’ position on the guilt or innocence of the captain serves to define them. Proust was a supporter of Dreyfus, and in one of the oddest moments of the period, he even signed a petition in support of Dreyfus, at the request of Anatole France. In September 1898, he even attended a defense rally at which the great socialist leader Jean Jaurès spoke.

But the Marcel Proust who defended Dreyfus was also a regular reader of only one newspaper, the royalist, anti-Dreyfusard, and antisemitic L’Action Française. Proust wrote that, though some of what he read in this Jew-baiting newspaper made him “sick to the stomach,” he praised the literary talents of its most celebrated writers, the ferocious Jew-hater Léon Daudet and the founder of Action Française, Charles Maurras. He likened the former to one of his literary gods, Comte de Saint-Simon, and praised the latter’s writing as being better than an “airplane ride, a high-altitude cure.”

Fully conscious of Daudet’s feelings toward people like his mother and grandmother, in 1895, at the height of the Dreyfus affair, he dined as he often did at the Daudet home. In a letter to his friend the composer Reynaldo Hahn (a Venezuelan-born Jew) Proust described the antisemitism of the observations Daudet made over the meal and wrote Hahn that Daudet’s reduction of everything to whether or not they had Jewish blood was “unintelligent. The most close-minded of intellectual concepts.” But he continued to frequent his dinners and admire his talent.

This might be chalked up to blind friendship, but In Search of Lost Time has a divided soul when it comes to Jews and Jewishness. To be sure, one of the most attractive figures in the book is the wealthy Jew Charles Swann, a man easily able to move in any circles he desires. But the treatment of the Narrator’s friend Albert Bloch again reveals the split in Proust.

The historian Saul Friedlander, in his insightful little book, Proustian Uncertainties, singles out the Narrator’s description of Bloch as a sign of Proust’s distaste for Jews. At one point Bloch is described as “bounding into the room like a hyena.” Friedlander reminds us that Proust had used the same unpleasant beast earlier when describing his friend’s entry to an aristocratic gathering, describing his hyena step as “crouching” and not “bounding.” Friedlander points out that “Hyenas are not known for bounding in any special way. The use of this unusual comparison to describe a person entering a room can only mean pushing oneself, entering by force or something similar. ‘Bounding like a hyena’ makes no sense, except that it indicates the narrator’s wish to be as insulting as possible … toward an old friend.” The Narrator, shorn of his ethnic roots, is a natural presence among the well-to-do. Bloch, being Bloch, i.e., a Jew, is an interloper.

The removal of the Jewish origins of Marcel’s maternal family results in a significant change in a scene that appears in both the preliminary manuscripts and the final work. In the completed work, the Narrator’s grandfather, stripped of his Jewishness, is convinced that his grandson was forever bringing home new friends who were Jews. To express his doubt of the Frenchness of the Narrator’s guests, he would hum tunes from the opera La Juive, signaling that the “Dupont” sitting at the table was very much not a Dupont. The guests were subject to a “dissimulated interrogation” and if his origins were admitted to grandfather would softly sing “This timid Israelite steps/You guide here among us.” Even as Proust insists no “malevolent sentiment” should be inferred from the grandfather’s conduct, he is clearly the holder of antisemitic opinions.

In an early notebook, this sentiment is expressed differently: Here the grandfather is Jewish, and he “didn’t like Jews,” or at least Jews of a certain kind: those who hid their Jewishness in an effort to assimilate. “In him, this was one of those little weaknesses, one of those absurd prejudices which can be found among the most upright natures.” This preliminary version of the maternal grandfather, too, would sing sections of either La Juive or Samson et Delilah, but now as a sign that he wasn’t duped, that he knew that despite his attempt at dissimulation, the guest was—like him—one of the Chosen.

The ambiguity of Proust’s Jewishness can be found in a letter he wrote in May 1896 to his friend Count Robert de Montesquiou, the snobbish model for the snobbish Baron de Charlus. Though the circumstances are not certain, we can gather that Montesquiou had unleashed an antisemitic tirade the night before in Proust’s presence. Proust explains in a letter written the next day that he was unable to answer the count “for this simple reason; if I am Catholic like my father and brother; my mother, on the other hand, is Jewish. You understand that this is a strong enough reason for me to abstain from this type of discussion. I thought it was more respectful to write you than to answer directly before a second interlocutor … [I]f our ideas differ, or rather if I don’t have the independence to have those I would perhaps have, you might have involuntarily wounded me in a discussion ... Of course, I am not talking about those that could take place between the two of us, where I will always be extremely interested in your ideas on social policy, should you lay them out for me, even if a reason of the greatest appropriateness prevents me from adhering to them.”

The delicacy with which Proust expresses his disagreement with his friend is impressive and speaks volumes of his wish to maintain the friendship and avoid a scene in public. But accompanying the delicacy is his distancing himself from his own background. He describes himself as “Catholic,” like his father and brother, which, given the fact that he was baptized is undeniable. But it is not he who is Jewish, but his mother, though given his mother’s religion he could make a claim to that status as well.

When Proust’s mother died in 1906, the “reason of the greatest appropriateness” that prevented him from sharing the antisemitism of the aristocracy was out of the way. He did not become an antisemite, and alongside his mocking of Bloch, his final work has sympathetic Jewish characters as well. But Bloch is a nagging presence, appearing at several places in In Search of Lost Time, as he attempts later in life to disguise his ethnic background by taking on a “French” name, one with the particule “du” that falsely elevates his social status twice, once to the rank of a non-Jewish Frenchman, and then into the aristocracy. (It should be noted that Albert Bloch’s new name, Jacques du Rozier, in a way points to his true ethnicity: Rue des Rosiers is a street in the Parisian Jewish neighborhood of the Marais.)

Bloch’s preciousness and his evident shame at being a Jew lead one to pose a question: Can it be that Bloch is so finely and convincingly drawn an example of a French Jew living in bad faith because he bears a not insignificant portion of Proust’s real-life persona? Whoever else was the basis for Bloch, it’s hard to avoid thinking that Marcel Proust contributed to the character. One can easily imagine Proust’s grandfather, in his disdain for assimilated Jews who hide their Jewishness, singing arias from Jewish-themed operas to expose Marcel as a shame-ridden assimilated Jew who has successfully elbowed his way into high society.