The Satmar Rebbe and the Destruction of Hungarian Jewry: Part 2

The late Rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum and his disciples’ interpretation of his decisions and actions during the Holocaust

This is the second of a two-part investigation into the life of the Satmar Rebbe. Read part one here.

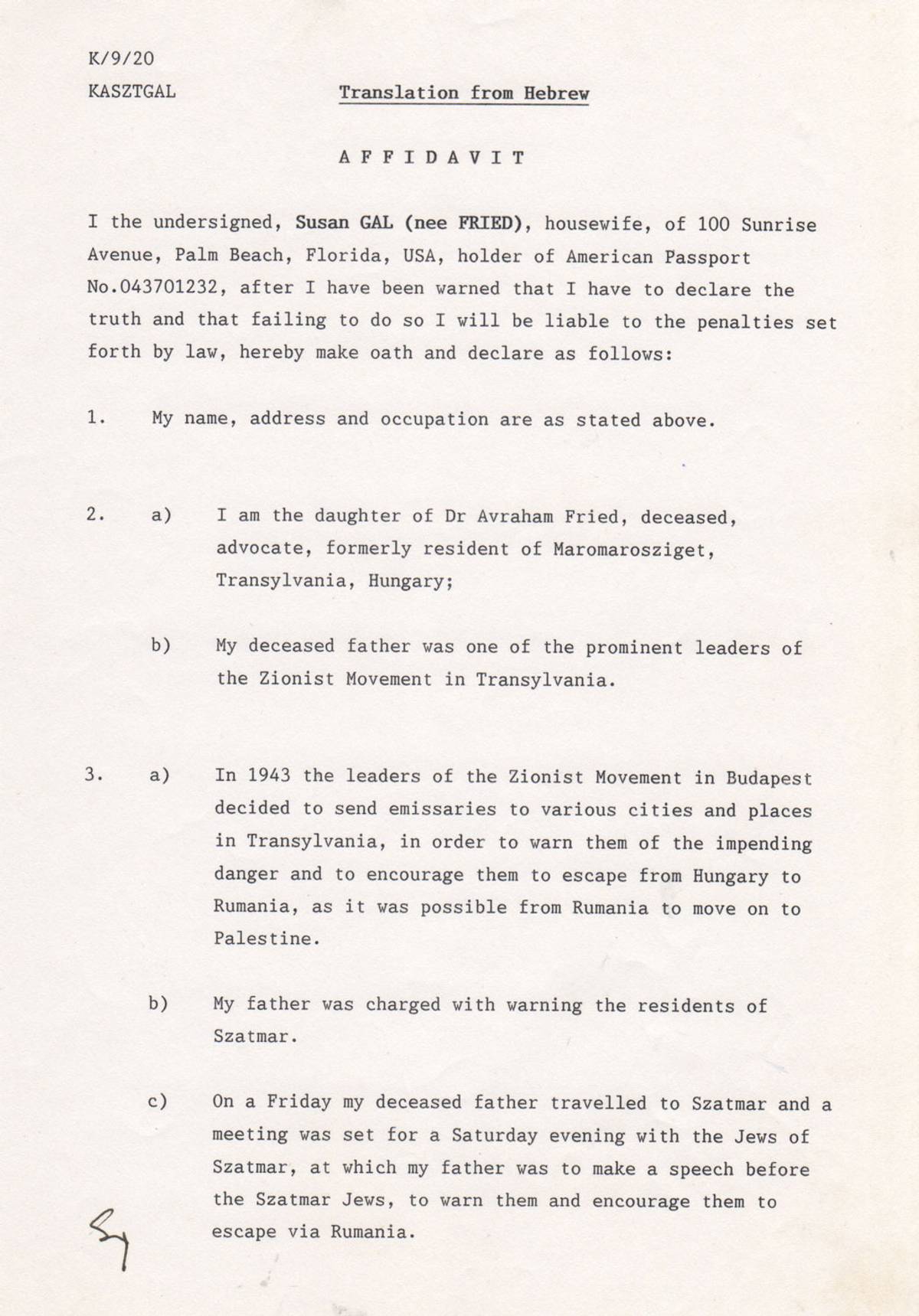

During his stay in the Cluj ghetto, Rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum hid rather than position himself as a leader. On the rescue train, he avoided the other passengers, failed to encourage or to comfort them, and did not share the precious commodities provided by his followers with them. In Bergen-Belsen, too, despite the preferential treatment accorded him in the camp, he refrained from assuming a leadership role, even among the observant inmates. After his release, Rabbi Yoel elected to run a rescue campaign from the safety of Switzerland. His efforts to rescue Jewish children raised by gentiles were restricted to fundraising, and even in that task he failed abysmally. Once again, his conduct stands in stark contrast to that of other rabbis, who returned to their hometowns to lead their surviving flocks or worked relentlessly in the DP camps. All the sources describing the rescue activities of the Haredi community during the Holocaust, including archival sources, indicate that compared to other rabbis who survived the Holocaust, Rabbi Yoel’s contribution was negligible in both scope and significance.

After the Holocaust, Rabbi Yoel also turned his back on all those who had helped to rescue him. After settling in Palestine in 1946, he refrained from expressing any gratitude to the people and institutions that had been instrumental in his rescue and had endeavored to obtain certificates for him, among them Chief Rabbi Yitzhak Herzog, Agudath Israel leaders Rabbi Yitzhak Meir Levin and Rabbi Moshe Porush, and Ha-Mizrahi’s Rabbi Joseph Yitzhak Rotenberg. He scathingly attacked the institutions they headed and, unlike other Hasidic rebbes they helped rescue, refused to make even the slightest symbolic gesture of gratitude. Moreover, it seems he repudiated his benefactors on a personal level, too. As far as we know, Rabbi Yoel never sent any letters of gratitude or appreciation to any of the people or institutions involved in his rescue.

Once settled in the United States, he spurned most of those who sought to assist him there, as well. He criticized Agudath Israel and the Union of Orthodox Rabbis of the United States and Canada, whose leaders had headed the Rescue Committee that endeavored to rescue the Hungarian Jews, including him. He treated Rabbi Elimelekh (Mike) Tress (1909–1967), leader of Tseirei Agudath Israel (the youth division of the Agudath Israel), and Rabbi Abraham Kalmanovich (1891–1964) somewhat more kindly, but then he ignored them when he no longer needed their assistance. When asked to testify on Kasztner’s behalf during his trial, Rabbi Yoel, whose inclusion on the Kasztner train was raised during the proceedings, refused. Thus, Rabbi Yoel repaid with ingratitude even the man whose name became most closely associated with his rescue from the extermination camps.

Criticism concerning his flawed conduct hounded Rabbi Yoel during the Holocaust and persisted thereafter. Therefore, Rabbi Yoel found himself compelled to explain, to himself possibly as well as to others, his objection to emigration to the United States and Palestine, his flight from the town of Satmar, and his participation in the Zionist Kasztner transport. His views on the Holocaust were never consolidated into a single contemplative text but rather were recorded in many of his works. The following are some examples:

• The Holocaust is God’s punishment of the Jewish people for its sins, and primarily for the sin of Zionism. The Zionist concept implied a denial of God’s ability to deliver his people and disrupted the natural place of the people of Israel, destined to remain exiled until the true deliverance.

• Zionism’s ultimate, undeclared goal was the spiritual annihilation of the people of Israel. Therefore, collaboration with those trying to cause the people of Israel to sin, that is, Zionist institutions, is strictly forbidden, even under threat of death.

• Zionists are the descendants of the Erev Rav (mixed multitude) and the Amalekites, so it is no wonder that they have caused the people of Israel such trouble.

• Any collaborators with Zionism, even the religious members of Ha-Mizrahi and Agudath Israel are also guilty of its sins. Therefore, the Zionist and the Haredi rabbis also bear part of the blame for the Holocaust.

• The Zionists bear the blame for the Holocaust not only because of their ideological concept, but also because of their actions, which included:

provoking Hitler and causing him to take revenge upon the people of Israel, obstructing emigration to other countries so as to force Jews to settle in Palestine, and the closure of their borders to immigrants following the demand to establish a Jewish state. Particular blame falls on the Zionists for deliberately preventing the Haredim from immigrating and thus saving themselves.

• The sin of Zionism was so grave that even its bitter opponents, Rabbi Yoel’s anti-Zionist followers were punished for it.

• The Holocaust was part of the redemption process. The Messiah’s advent, destined to occur during its course, was impeded by the Zionists’ actions and the intervention of Satan.

The author of the single, brief biography of Rabbi Yoel written during his lifetime completely ignored the Holocaust period. Several posthumous biographies, authored mostly by his Hasidim, were required to explain the rabbi’s conduct during the Holocaust. The subject was not dealt with in a coherent or deliberate way, and the various authors found different solutions to a number of issues. Over time, the coping modes changed, and in recent years, apologetic attempts to conceal or ignore difficulties have been replaced by a “counter-offensive,” designed to undermine what the authors perceived as “Zionist claims.” The following are some of the modes and claims used in addressing Rabbi Yoel’s decisions and actions during the Holocaust:

• Rabbi Yoel merely opposed organized immigration to Palestine, not the immigration of individuals wishing to lead a Haredi lifestyle. Jewish settlement in Palestine prior to the Holocaust would not have prevented the danger, as the German army was already on its way and only by a miracle never reached it.

• The Zionists took advantage of the dire straits in which the Haredi Jews found themselves, forcing them to join their ranks and thus to corrupt their souls.

• Rabbi Yoel had never sought to flee and abandon his congregation, yet his capture by the Germans would have been disastrous for his followers. He encouraged many to flee the ghettos, and the purpose of his escape was to continue his rescue efforts outside of Hungary.

• Rabbi Yoel was among the initiators of the negotiations with the Germans, and his inclusion on the Kasztner train was the result of a demand made by Haredi leaders, rather than a generous offer by the Zionists.

• The Zionists collaborated with the Germans by failing to publicize the danger threatening the Jews in Hungary. Moreover, they impeded the implementation of rescue plans and discriminated against the Haredi population in the allocation of certificates by making the signed acceptance of Zionism a prerequisite for the granting of certificates.

• The Zionists covered up Haredi rescue initiatives and in particular their role in the rescue of Rabbi Yoel. They accused Rabbi Yoel of opposing settlement in Palestine, although they themselves permitted only selective immigration and blamed the Haredi leadership of endeavoring to save the rabbis alone.

Rabbi Yoel founded his congregation in Williamsburg, New York, shortly before the establishment of the State of Israel. His anti-Zionist attacks and delegitimization of Israel by blaming Zionism for the Holocaust served to consolidate the congregation’s unique identity. Within a few years, it attracted hundreds of Hasidim and became known for its reclusive lifestyle and radical religious views. Unlike other Haredi communities in the United States, Rabbi Yoel supported the Edah Ha-Haredit of Jerusalem, whose institutions were on the verge of bankruptcy after donations from Eastern Europe dried up during the Holocaust. In gratitude, it appointed him its first president and subsequently ga’avad (chief rabbi of its Rabbinical Court). In 1954 he founded the Central Rabbinical Congress of the United States and Canada (Hit’ahdut Ha-Rabanim), uniting rabbis whose religious views were anti-Zionist. In the provocative demonstrations it held in New York and Washington, the organization vilified the State of Israel for “trampling religion” and accused its government of “Nazi” treatment of the Haredi community. Following the publication of Rabbi Yoel’s anti-Zionist polemic books, he emerged as Zionism’s bitterest ideological opponent.

The demonstrations triggered a public discussion of Rabbi Yoel’s conduct during the Holocaust. One of the criticisms leveled against him, both within the Haredi community and in the Israeli press and academic literature, focused on his rescue aboard the “Zionist” Kasztner train. This main argument was that at a time of crisis, with his own life at stake, Rabbi Yoel availed himself of the Zionists’ help to save himself. Historical perspective suggests that Rabbi Yoel warrants even harsher criticism, beyond the issue of his escape on the Kasztner train. Toward the end of his stay in the Cluj ghetto, he probably assumed that he had already lost the majority of his Hasidim. He was not familiar to most of the ghetto’s inmates and had no moral obligation to them. Thus, the issue of his obligation to his congregation was no longer relevant, and the question of whether to save himself by any means possible was irrelevant, both morally and by halakhic ruling. In such circumstances, the halakhic principle of piku‘ah nefesh, the obligation to save a life in jeopardy, as well as his human instinct, left him with no other choice.

Yet the true moral issue regarding Rabbi Yoel’s conduct during the Holocaust pertained to his earlier escape attempts. When he first tried to obtain certificates, he was already aware that the lives of Hungarian Jews were in danger. At that point in time, the question of whether it was permissible, both from a halakhic and an ethical perspective, for a spiritual leader of a large congregation to abandon his flock in its hour of need to save his own life could have been considered sensibly and in a level-headed manner. With the passing of time, and as the danger became ever more palpable, it became easier to make excuses for Rabbi Yoel’s flight.

Another moral issue is presented by the fact that Rabbi Yoel, who forbade emigration to Palestine and all the more so through Zionist organizations, did not apply the same strict prohibition to himself even though his economic and public status enabled him to emigrate to other destinations. Additionally, one cannot help but wonder why Rabbi Yoel did not alert the public about the dangers to which he became privy during the early 1940s. Moreover, he opposed all initiatives to prepare for the imminent danger and failed to set either a practical or moral example to his numerous followers. Another moral issue concerns the fact that despite his fierce opposition to Agudath Israel, even during the Holocaust, he availed himself of the help of the Agudah’s members and supporters. After the Holocaust, ignoring

his moral indebtedness, Rabbi Yoel turned his back on his benefactors of all camps.

The answers to these moral issues cannot be found in the explanations and excuses provided by Rabbi Yoel himself and his Hasidic biographers. Yet during other periods in his life, one can trace clues that may explain his behavior. On previous occasions, such as World War I and during the Goga regime, Rabbi Yoel had abandoned his congregation and moved to a safer area, where he stayed until the danger passed. This conduct corresponds with other accounts that describe him as a fear-ridden, anxious individual. This fearfulness of his manifested itself during the war years, when he refused to cooperate with other rabbis’ and the Central Bureau’s attempts to set fast or prayer days. He likewise refrained from making any clear pronouncements on halakhic matters when he thought doing so could endanger him. Therefore, it appears that his conduct stems, at least in part, from his fearful nature, rather than from any pertinent or halakhic considerations, introduced post-factum to justify this conduct.

Rabbi Yoel’s personality may also serve to explain his treatment of his congregation, closest associates, and saviors. From an early age, his relations with his family were strained. He was angry with his brother for not allotting him a share in the inheritance left by their father, which consisted of the town’s rabbinate, management of the yeshiva, and leadership of the Hasidic court. After his brother’s death, he considered his relatives traitors for not appointing him in his place and choosing his 14-year-old nephew instead. His life circumstances further hardened his character: His parents, brother, first wife, and two of his daughters died before the Holocaust. His wives failed to bear sons and his daughters, grandsons. His rigid, uncompromising character was well reflected in the bitter, relentless campaigns he waged against political opponents, against whom he schemed and whom he slandered both openly and surreptitiously.

Rabbi Yoel’s interpretation of the Holocaust and the accounts of that period of his life in posthumous Hasidic biographies have surrounded his character with numerous excuses and explanations, all of which seek to refute criticisms of him. Upon examination, these arguments, many of which are based on the demonization of both Zionism and Zionists, show that the principal questions remain unanswered: Why did Rabbi Yoel fail to warn his followers before the Holocaust? Why did he try to immigrate to Israel after forbidding his followers to do so? Why did he thwart attempts at cooperation, which could have saved so many lives? Why did he not set a personal example for his Hasidim? Why did he abandon his congregation, incarcerated in ghettos, and flee in the middle of the night? How did he come to abandon his closest friends in the Cluj ghetto? Why did he board the Kasztner train, which was organized by the abhorred Zionists? Having survived, why did he never return to rebuild his congregation in Satmar? Why did he refrain from assisting in the spiritual and religious rehabilitation of the Holocaust survivors in the DP camps? Why did he alienate himself from Agudath Israel and the Zionist organizations that had helped to extricate him from the Nazi horrors? And why did he adopt such radical stances, such as blaming the Holocaust on the Zionists, to justify his actions and decisions during the Holocaust?

Apparently, these questions are fated to remain forever unanswered. Regardless, no postfactum claims and explanations can cover up Rabbi Yoel’s incompetence in leading his community during the early stages of the war, his escape efforts during the Holocaust, and his subsequent failure to assist those who survived it.

Menachem Keren-Kratz, a researcher of Hungarian Orthodoxy and of contemporary Haredi society in the State of Israel, is the author of Maramaros-Sziget: Extreme Orthodoxy and Secular Jewish Culture at the Foothills of the Carpathian Mountains.