The Scholar and the Survivor

In a compelling new memoir, ‘Reading Claudius,’ Caroline Heller goes in search of her formidable uncle Erich, whose WWII legacy still haunts his descendants

One of the ironies of the 20th century is that the best critics of modern German literature were Jews. If you want to understand the literature of the country that perpetrated the Holocaust, you have to turn to Walter Benjamin on Goethe, Georg Lukacs on Thomas Mann, and Marcel Reich-Ranicki on Gunter Grass. This situation was the source of no small pain and confusion to German-speaking Jews themselves, who loved the German language and German Kultur without finding their embrace returned. As early as 1912, in the essay “German-Jewish Parnassus,” the critic Moritz Goldstein pointed out that German culture was being largely administered by Jews, who were said to be spiritually incapable of understanding it.

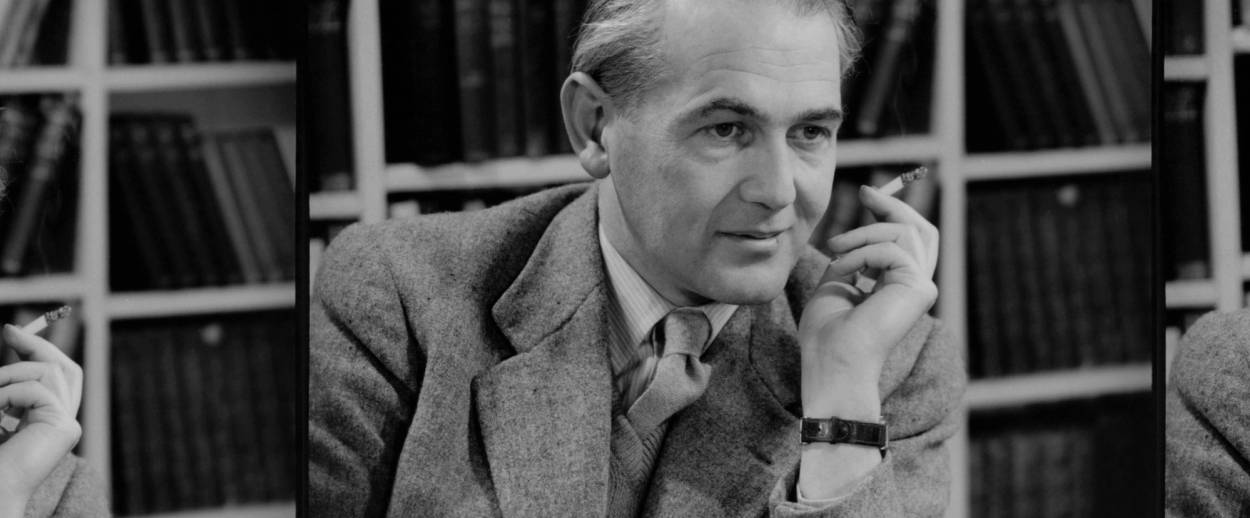

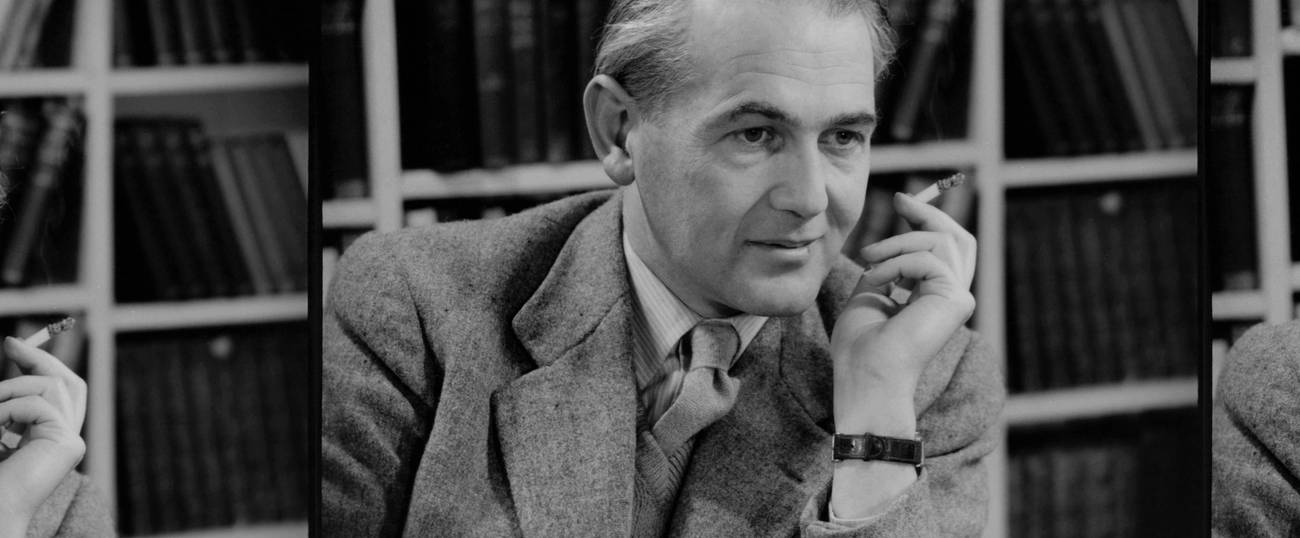

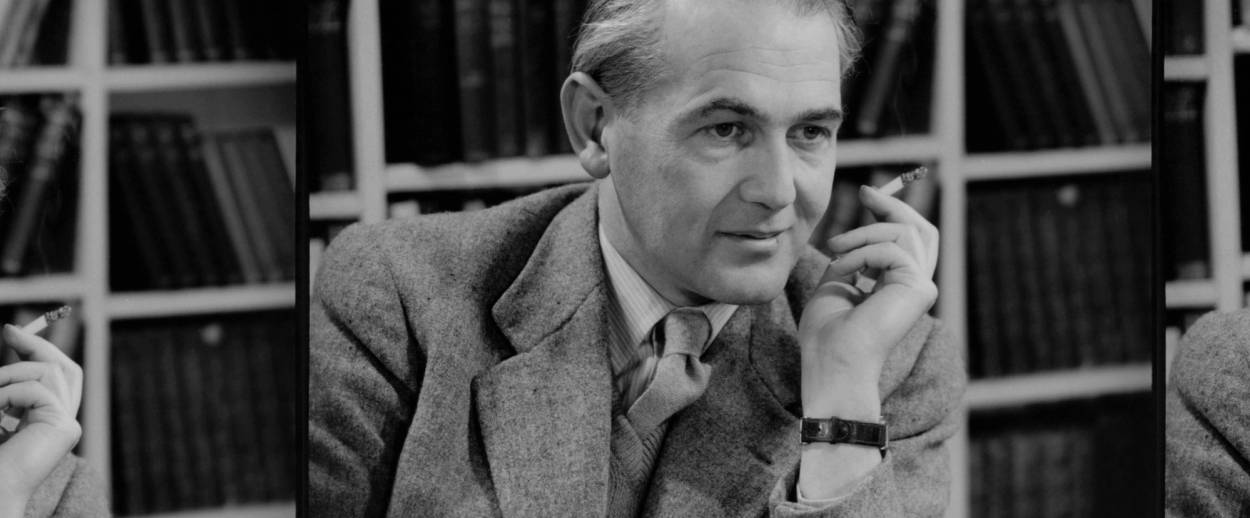

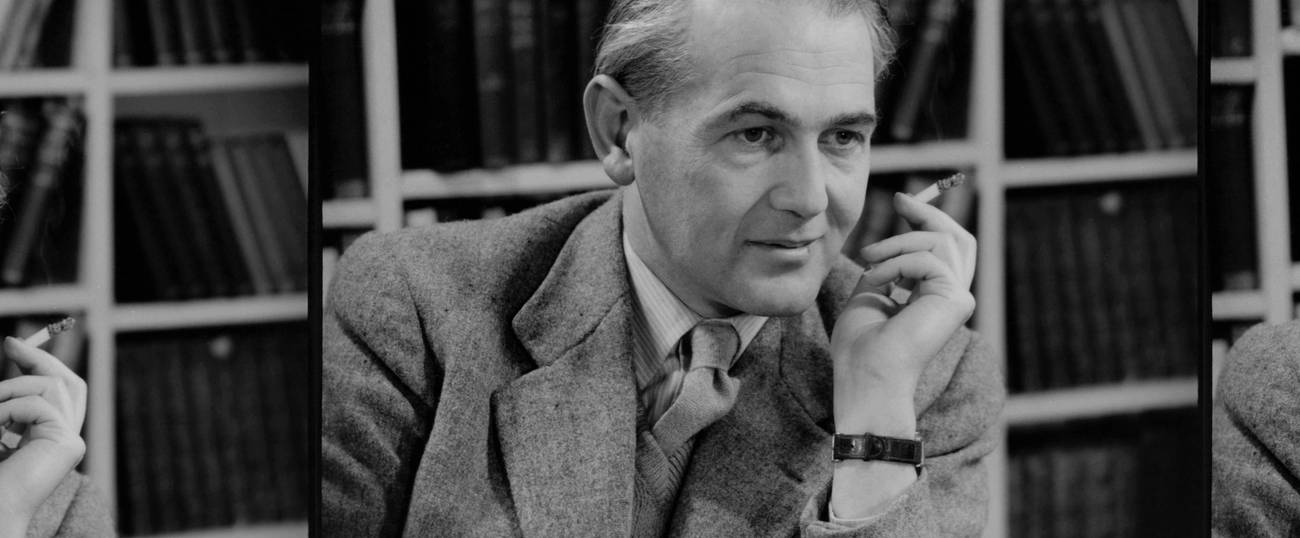

I don’t know how many readers outside of academic German studies still remember the name of Erich Heller, but in the postwar period he was one of these great Jewish interpreters of German literature. He was born in 1911 in what would become the Sudeten region of Czechoslovakia, which the Nazis took over following the notorious Munich deal of 1938. After Nazi Germany absorbed the rest of the country in 1939, Heller fled to Britain. This fateful emigration meant that he built his career as a writer and teacher in the Anglosphere, first at Cambridge and later at Northwestern, and he stood near the center of Anglo-American intellectual life, cultivating friendships with everyone from Isaiah Berlin to Hannah Arendt to W.H. Auden.

There is, however, at least one person who will never forget Erich Heller: his niece Caroline Heller, author of the flawed but compelling new memoir Reading Claudius. Caroline, we learn in this book, grew up in the 1950s as an American child in a prosperous suburb of Chicago, where her father Paul (Erich’s younger brother) was a doctor and her mother Alice a social worker. Yet she remembers her childhood as a long, failed attempt to fit in with American culture—“how we should look and who we should be,” as she puts it. Family life was anxious, dominated by her father’s “chronic sense of pending disaster,” and as a young girl she absorbed this feeling, which gave rise to bouts of depression and anxiety. Starting kindergarten was as hard, Heller recalls, as going to college would be 12 years later: In each case, she felt torn from the safety of her home, forced to adapt to a hostile world. She quotes a letter she wrote to her father at the age of 18: “I hardly think your lonely thoughts for me can compare with mine for you. … I wish we could stick together always.”

The reason for this despair and fearfulness was the same reason the Heller family was the only one in the neighborhood not to have any family photographs on the walls. As Caroline Heller came to learn only as an adult, her father had been an inmate of Nazi concentration camps from the first day of World War II to almost the last, spending time in Buchenwald, Dachau, and Auschwitz. Her mother had managed to flee Prague for New York just in time but struggled to adapt to her new country. Their way of protecting their American children, Caroline and her brother Tom, from this legacy was to hide it, or at least to let it remain hidden. “I don’t believe my parents made a conscious decision to hide our Jewishness from my brother and me as we were growing up,” Heller writes. “Nor do I believe they made a deliberate decision not to tell us about the losses that formed their lives before we were born.” Rather, “there was a tacit family agreement not to ask certain questions.”

This kind of conspiratorial silence about the past, with its concomitant anxiety and dread, is one of the ways the Holocaust exacted its toll on the second generation. Recently there has even been some activism devoted to the third generation of survivors. And while the travails of these later generations may seem trivial compared to what actual Holocaust survivors went through, Reading Claudius proves that in fact it was a real psychic injury. You could even go so far as to say that the Holocaust has inflicted serious psychological damage on Jews whose ancestors were never anywhere near a concentration camp, simply by filling Jewish minds with the fear and the imagery of extermination. Like other wars, genocides, and atrocities, the Holocaust is an evil that keeps reverberating long after the actual killing is done.

One of the time-honored ways for the Holocaust’s heirs to come to grips with its legacy is to write about it—to shine light on what had been hidden, to reconstruct the vanished world. Books like Daniel Mendelsohn’s The Lost and Edmund de Waal’s The Hare With Amber Eyeshave managed to connect with wide audiences because of the cathartic effect of such recreation: Instead of rupture and erasure, the Jewish past is filled with identifiable people and understandable stories. This is what Caroline Heller has done, on a smaller scale, in Reading Claudius. While we get to know a certain amount about Heller herself—her childhood trauma, her adult redemption, her sexuality—the directly autobiographical section of the book is short and doesn’t come until the end. The bulk of the book is devoted instead to Heller’s parents, Paul Heller and Alice (originally Liese) Florsheim, and their circle of friends in prewar Prague, including most centrally Paul’s brother Erich.

Rather than structure the book as an account of her own quest for the past, however, Heller narrates that past in the style of a novel, complete with invented details and dialogue. In her prologue, Heller explains this approach as a kind of reparative wish-fulfillment: “Unable to know my parents’ and uncle’s early world in its fullness, I tried in this way to approximate a representation of its wholeness. Doing so was my way of fulfilling a lifelong yearning to literally make my parents’ world whole again.” Yet the result can only be a spurious kind of wholeness, which inspires suspicion in the reader in exact proportion to its claims to specificity. Take, for instance, Heller’s habit of taking quotations and ideas from Erich Heller’s published postwar work and attributing them to him as spoken words in the 1930s. Or take the moment when Heller describes her mother “walking across Charles Bridge” in Prague, and feeling “the backs of her legs tighten” during a tense conversation. Is this physical detail something her mother related to Heller late in life, when she finally began to open up about her past? Or is it imagined, a way of bringing the reader closer to the characters, in the way a novelist might do?

Was Erich Heller wrong to escape the Nazis, or to live the life of the mind as best he could at a time when that life was being extinguished in Germany?

Such questions and doubts mean that the reader cannot take Heller’s account of 1930s Prague as simple fact. Especially after we read the last portion of the book, which describes the slow and tortuous process by which Heller became aware of her parents’ stories, we realize that her understanding of that past is necessarily colored by her own feelings about her parents and relatives—above all when it comes to Uncle Erich. As a child, Caroline writes, Uncle Erich was a disruptive visitor, whose fame (and bragging about that fame) made him intimidating: “When he spoke, it was as though all of Europe were talking, the words carrying my parents away. … In Uncle Erich’s presence, I found it almost impossible to speak.”

This resentment in turn shapes her portrait of the young Erich, who was—to make matters even worse—her mother’s suitor years before Paul. Erich Heller comes across in these pages as a conceited blowhard, always talking at people, and behaving dishonorably when he gets Liese pregnant during their one ill-fated attempt at lovemaking. Only later is it revealed that in fact Erich was gay, which must account for his ambivalence toward Liese, though it doesn’t win him much sympathy from his niece.

The most devastating part of Caroline Heller’s portrait of her uncle, however, comes in the chapter comparing Erich’s and Paul’s wartime experiences. After the Nazi takeover of Czechoslovakia, Erich and two friends tried to escape over the border to Poland, only to be arrested by the Gestapo, who knew about his anti-Nazi writings. He spent a month in prison before he was able to escape, with the connivance of a friendly guard, whereupon he made it to England and was accepted as a doctoral student at Cambridge. The result was that Erich spent the war years in an idyll of reading, thinking, and writing, while Paul, who was arrested at his home in Prague on the day war broke out, spent six years being starved and tortured almost to death. Heller sharpens the contrast by printing alternating passages of Erich’s wartime letters (“Last week in Cambridge I heard a lovely concert … the 4th Piano Concerto by Beethoven, 5th Brandenburg Concerto, and Mozart’s Linz Symphony. It is so important to remember that this world still is!”) and Paul’s memoirs written just after the war (“We’re ordered to load stones into handbarrows and carry stones while running. … We have to pass a row of SS guards with whips”).

Add to this the suggestion that Erich’s escape from prison was dishonorable—bought with sexual favors, or even by informing on his brother, as Caroline Heller seems to intimate in her endnotes—and you have what is surely supposed to be a damning portrait. But was Erich Heller wrong to escape the Nazis, or to live the life of the mind as best he could at a time when that life was being extinguished in Germany? If so, we ourselves are equally guilty of going about our lives, while people are being massacred every day in Syria’s civil war and elsewhere. Another version of the story, told by a more neutral observer, might leave us with a very different impression of Erich Heller. But that is the thing about family stories: The people who tell them are always still in the middle of them, just as we are all still in the middle of the Holocaust’s history.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.