She Invites You

The ultimate moral test of any society is the way it treats its most vulnerable

Original images: Chen Junqing/Xinhua via Getty Images; Alexi J. Rosenfeld/Getty Images

Original images: Chen Junqing/Xinhua via Getty Images; Alexi J. Rosenfeld/Getty Images

Original images: Chen Junqing/Xinhua via Getty Images; Alexi J. Rosenfeld/Getty Images

We sit on a rock jetty, coffees in hand. We’re quiet, watching two groups of surfers—experts slashing the short, powerful waves at the break and children in wetsuits in the whitewash, learning to stand on their boards for the first time.

The late day’s sun is half a fist’s height—half an hour—above the horizon, blocked now by dark, ominous clouds moving above the Mediterranean.

She has come back home, to the place of her birth, to play a Nova survivor—one who hid in a port-a-potty for hours—in a new television series. At first, I think it’s too soon—for her, for the nation—to see these things portrayed. But it’s not for our nation, she tells me, it’s for others. She, they, are desperate to be believed. But more than that, they’re desperate to be understood.

I, an American, am here to visit my nieces. To visit the Nova site, Kfar Aza and Be’eri. For research, like her, but not for a role. For my soul. For them—someone else’s nieces who danced and danced and then ran and fell. Who were cut down by monsters or dragged away to hell.

The kids get out of the water. The experts too. The storm has gained speed. It starts to rain. Large, fat drops. Liquid hail.

We put up our hoods and walk toward the hotels, toward the city for a beer, sad to miss the sun setting into the water.

We rush up some stairs, the wind pushing against our raincoats like gusts into a sail.

A middle-age woman stands at the crosswalk, stretching a hand toward us, gently asking for help crossing the street.

She leaves my side and takes the woman’s hand with her left arm, drapes her right around her shoulder. They proceed together, cautiously, one step at a time to accommodate the woman’s contorted legs, her feet dragging through the puddles like slow boats.

I step between them and idling white taxis, feeling protective.

-Look, she says to me, pointing.

A rainbow. I take a photo and send it to my “mishpacha” group chat.

-Do you mind if we walk her all the way home? It’s only 10 minutes.

-Of course.

I hear the woman speak as slowly as she walks. But with purpose, in both.

I only understand a few of the Hebrew words my friend says in response. Nachon. Ken. Shabbat.

Her head rests on the woman’s shoulder. Their arms still intertwined like a challah.

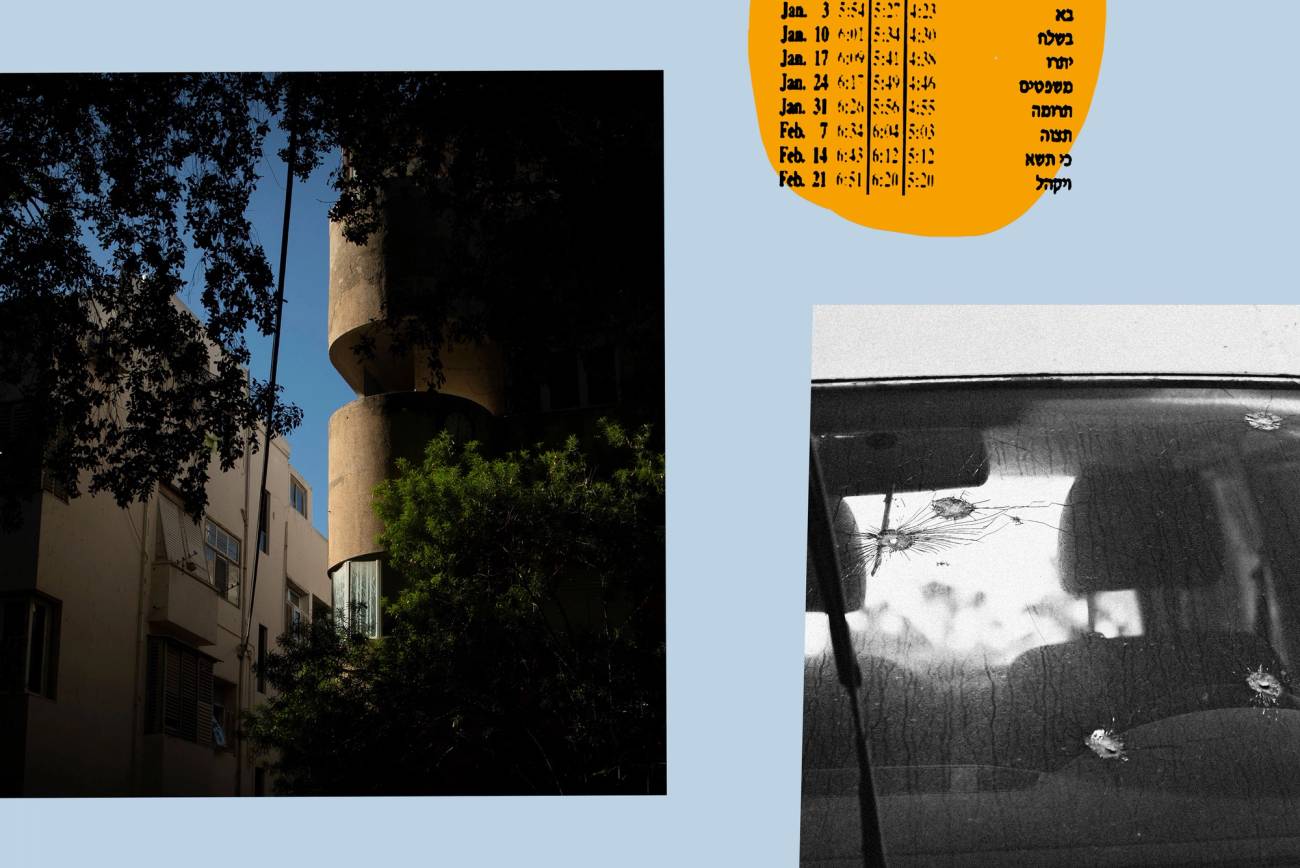

We reach a yellow Bauhaus building, and the rain has stopped, the rainbow brightened.

-I’ll walk her upstairs, wait here. Five minutes, she says.

I admire a long-haired dachshund, like one my grandmother once had, walking with its head held high on the other side of the street.

My phone buzzes in my pocket.

Do you want to come up and light the Shabbat candles? She invites you.

Of course.

Second floor.

There is no elevator. Silver mailboxes with key holes. Mud on the tiles.

-Hello? I call on the empty second-floor landing.

-Up here.

I’d forgotten that here floor 1 is 0, and floor 3 is floor 2.

The apartment is bright and clean. Large windows, a paisley tablecloth with a place setting for one. A dragon tree in a white pot next to a painting of Technicolor toucans on the wall. A newspaper open to a half-completed Hebrew crossword on the counter. Smells of my grandmother’s soup. Magnets on the fridge.

-This is Maya (name changed to protect anonymity), she says.

I introduce myself, waiting patiently for her to raise her arm, shaking her fragile, damp hand.

I see her beautiful face for the first time, her denim skirt and white sweater. Her curly, wet brown hair.

-She says we’ll wait just one minute, until the sun sets. She’s observant.

We stand still, smiling to each other. Then Maya, hand quivering, strikes a match and begins to sing the familiar melody. We join. They light the candles.

-Shabbat shalom, we all say, hugging.

Outside, her arm wraps around my shoulder now.

-I know, she says. I know.

-In what other country? I ask.

Later, I stand on the balcony of a friend’s apartment on the 34th floor. The burnt yellow lights of the city are still, without shimmer, against the bottom of the black sky.

-How far is a kilometer and a half? I ask, looking out to the south.

-See the red light just there? he says, pointing.

-I’m color blind.

-See the bend in the road?

-Yes.

-That’s about 1.1.

-And how accurate can you be at that distance? With the wind? The curvature of the Earth?

He holds up his palm and points to its center.

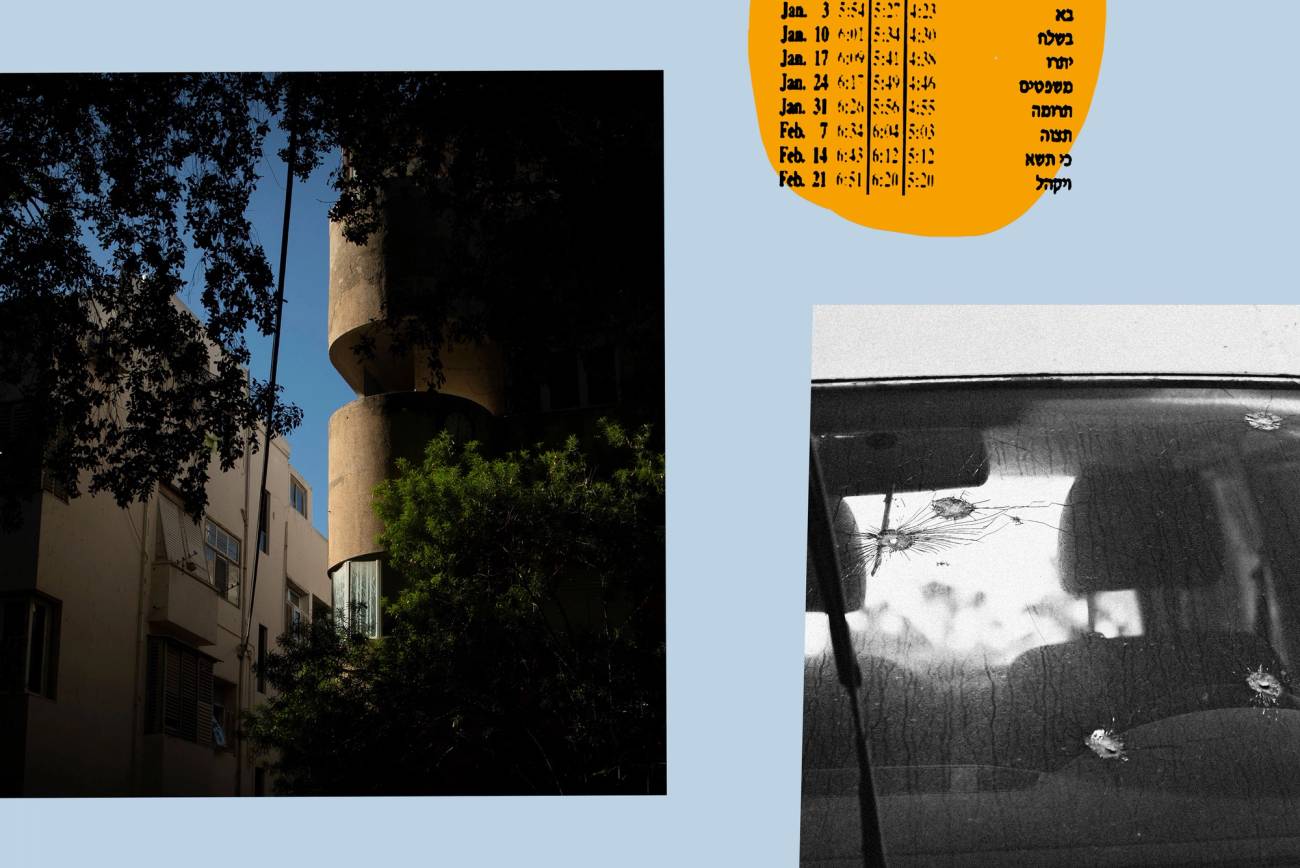

He was a sniper in the army, a sniper in reserve. He served on the Gaza border. He does not know how so many got in. Where the snipers were that day. But he knows things had changed, slowly, over time.

-It used to be we had orders to shoot anyone who got close to the fence, only in their legs. But then they came out with children, babies, strapped to their shins, he says. So we stopped shooting. They kept probing, gathering intelligence. For a few years. Planning. They hid behind piles of sand, sending men with Down syndrome to the fence with explosives, he says, shaking his head. If the protesters in your country had seen that, then maybe they would know.

-I’m not sure, I say. They don’t seem to care.

I see Maya’s neighborhood in the distance, close to the sea, the blessing for the candles echoing softly in my ears.

Jackson Greenberg is a Los Angeles-based writer and composer.