One day, sometime in the 1970s, poet and thinker David Antin walked into an auditorium at Pomona College, in Southern California, to deliver a reading. This time, however, he did not bring the traditional paraphernalia poets bring with them to such occasions: books with folded pages, manuscripts, notepads, scraps, or any other texts to read off from. Instead, he cleared his throat, and began to speak—to improvise, spontaneously weaving together ideas and images, anecdotes and insights. Afterwards, replaying the tape of the recorded performance during their drive home, the poet’s wife, performance artist and filmmaker Elly Antin, pronounced: “That’s a poem.”

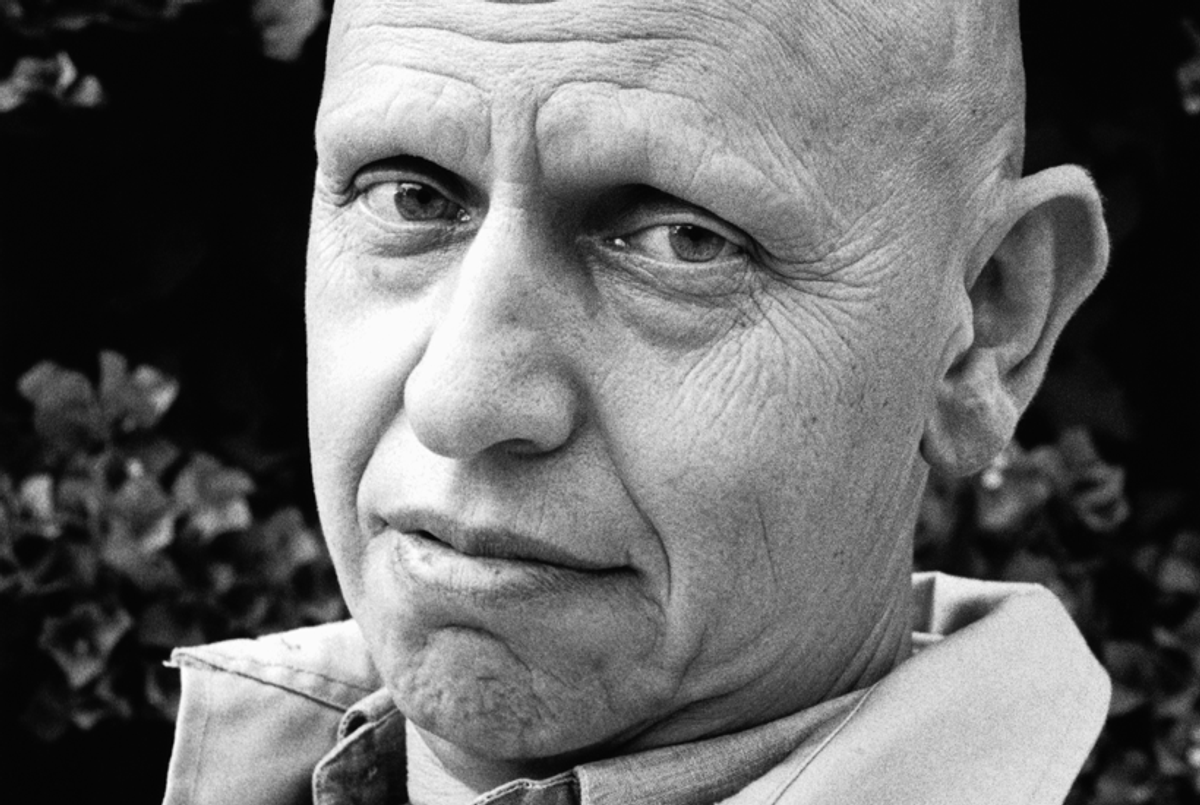

How Long Is the Present, published last month by the University of New Mexico Press is a selection of transcribed talks, known as the “talk poems,” which Antin gave during the period from the mid-1970s to the early ’90s. The volume also includes a thorough introduction by Stephen Fredman, as well as a recent interview with the author, who turned 83 this week.

your definition of the real is more like a hope about things that should prove to be real the real is like a construction something that builds piece by piece and then it falls on you or you move into it

So runs one of his trademark talk pieces, manifesto and poem in one. The particular mode of formatting here reflects Antin’s cadences—the rhythm with which he speaks as he pauses to think, and to deliver his points with the timing worthy of an actor or comedian. Antin’s idea of poetry—so different from the traditional verse with line-breaks, stanzas, sonorous wordplay, and musical rhythms—is not merely unique. His genre includes only one practitioner. The confluence of expansive knowledge, sharp wit, and the gumption to improvise is not representative of an idea or tendency, but rather of Antin’s very persona.

Antin has been seen as a link in the long lineage of Jewish stand-up comedians, rhetoricians of Antiquity, post-modernist philosophers—yet, somehow, he still remains a poet. It is as if he belongs to a very different era, or a mindset, quite apart from traditional, and even experimental, worlds of American poetry.

There’s a great thrill and mystery to improvisation. Those who love it and seek it out know well the sudden realization—the intuition’s kick, indicating that performance is being born not of memorized, long-rehearsed movements, but in real time, in front of the audience’s eyes. Looking forward to my meeting with Antin, I set a goal of going beyond a regular interview—the traditional volleying of questions and answers that may or may not get me closer to comprehending the maestro’s technique. Instead I was hoping for a wider experience that would allow me to touch upon the essence of improvisation—and poetry—as purported by one of its greatest living masters.

***

Driving down Highway 5, a half-hour’s drive from the San Diego airport to the Antins’ residence, I took a few detours and wound up near the ocean, thinking: This may be the strangest town for an avant-garde artist to live in. Ships sunning in the marina, umbrellas over December sand, middle-aged folks with great bleached hair, and short shorts in the beachside cafes: There’s something paradisiacal, unrealistically comfortable about San Diego. My GPS struggled to find the exact address, and I followed the directions Antin had emailed to me in anticipation of my arrival—the directions from the point where the road ends: “Turn left again and drive 90 yards. Turn left into our gravel paved driveway and park. There is a brick paved walkway that leads to the house.”

As poet and scholar Maria Damon pointed out, the key to Antin’s appeal is his ability to freely swing between highbrow and lowbrow cultural references—to go from complex abstractions to hilarious personal anecdotes, to engage with life’s fundamental questions in a way that is sophisticated and yet somehow folky, all told in casual, vernacular talk, peppered with his distinct New York accent. Assessing his own method in the third person, in one of the talk poems published in How Long Is the Present collection, Antin invites the audience into an imaginary location, a terrain where he hunts for ideas:

… the one who comes there and has been thinking of talking is a kind of agent provocateur he is the one who comes bringing troubles and has been preparing to unpack his pandoras box of them and leave them with you for your entertainment and most people wishing to be entertained or willing to be in the way that ideas are entertained or entertaining

In a moment of characteristic wordplay, he indicates that entertainment, in his estimation, is not a Hollywood-style thrill. When we entertain ideas, we give rise to a possibility—we play around with reality that may or may not transpire. To be entertained by Antin is to come along for a ride across disciplines, to watch him stand up in front of his audience and think, poetically, right there and then, through ideas that intrigue him—“troubles”—which often have to do with nature of thought itself, language, and art more broadly.

As I parked the car, I followed the “brick paved walkway” toward the Antins’ house prepared for anything but what I saw: a tiny young woman, barely dressed, sunning on the ground near the house. It was a statue, of course, but it took me a minute to grasp that, and as I walked on, to catch a magnificent view of the hills surrounding the house. The Antins settled in San Diego following David’s appointment at the University of California, San Diego, as a professor of visual arts and a curator of the local art gallery. As David described his digs, “We have been protecting this property for quite some time.”

You could say the day’s performance started shortly after I knocked on the door and shook hands with the poet. Antin gave me a tour of the grounds surrounding the house—the garden filled with short trees and flowering cacti, well-loved overlapping paths. David showed me into his wife’s studio, a spacious, long, wagon-like room with floor-to-ceiling windows, suspended between the house and a hilly mound right next to it. Elly, David, and I began to talk, and over what seemed like a very short slice of time, moving from studio to the dining room, we covered a quite a bit: extremism, secular Yiddishists, Stalin, inherent fallacies of language, Middle-East, feminism, transgender etiquette, and of course our personal histories.

Antin’s gift is to converse, and while conversing, to peer through the lens of self-awareness, to examine what it is he is saying, assessing whether he believes his own words and notions, as they occur to him. Later, when we settled down for the interview he clarified:

“What do I mean? It’s not I who does the meaning. It’s as if the meaning comes of the culture speaks through me I feel myself in awareness of cultural reverberations of every word And I’m doubtful of what I’m saying My doubt is what makes it improvisational.”

Thinking of improvisation, we may imagine near-prophetic rants, ecstatic overflow of free-associative images and visions famously espoused by the Beat poets in the 1950 or ’60s—or manic jazz solos that were soaring high around the same time. Not so with Antin. His entryway into improvisation is through ecstasy’s very nemesis, or foil: the doubt.

Antin’s peculiar brand of doubt has something to do with the fact that he—as he said of his colleague and friend Jerome Rothenberg—“never gives up that Jewish shrug of the shoulders.” The shrug as a philosophical trope is tendency one could trace as far back as the Talmud. From one tractate to the next rabbis evaded answers so as to prolong conversation, leave doors open rather than bolted shut with conclusion.

Controversy and challenge of the established norms are of course part of Antin’s appeal. As he put it repeatedly, he chose to improvise because he did not want to present regurgitated, finalized, “dead” ideas, but rather, fresh, living, ideas that come to life in a moment. As Antin recounts the episode in the talk piece,“what it means to be avant-garde,” Harold Bloom, probably the most well-known and vocal American literary critic working out of Yale University, once stormed off the stage when another critic delivered a talk on Antin’s work. The professional sort of poetry—the kind Harold Bloom approves of and that is expected of, say, a U.S. Poet Laureate—is polished and is precisely the sort of experience that Antin’s work opposes. As he elucidated in one of the talk poems:

everyone knows there is a professional baseball player and an amateur but you don’t say theres a professional lover and look approvingly at that person who may be a gigolo or a courtesan and you don’t turn around and say scornfully of some passing lady who may be somebodys lover “shes an amateur” because in love you dont want to be a professional.

Given the personal, vocational nature of Antin’s work, it is no surprise that a great deal of anecdotes and stories show up in his talks. One story I remembered well had to do with the poet’s esteemed ancestor Wolf Kitzes, a Hasidic rabbi and a legendary associate of the Baal Shem Tov. In Antin’s rendition of the story—based on Martin Buber’s version of the folk legend—sent by Baal Shem on a mission, after a long journey, Kitzes finds himself in a palace unlike any other palace in the world. It was a dwelling of the Divine, and the disembodied voice asked the Hasid: “How are my people doing?” And, as Antin imagined it, came Kitzes’s reply: “How should they be doing?”

As we recalled Wolf’s story, I asked Antin how he thought the Jews were doing. He replied:

“I think Jews always managed to do as well as it was possible because it’s an intellectual tradition people are looking for something better than victory in some sense they seem to be dedicated to understanding or something like it there’s a form of humanity that’s very rich and seems to emerge from Jewish intellectualism I think it is about being very hopeful that greater intelligence is available from the tradition of the Torah the questions are about silly things often, the structure of the arguments wonderfully entertaining some are brilliantly handled so it’s a kind of a richness of discourse and a triumph of vision in which discourse stands for a great deal.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jake Marmer is Tablet’s poetry critic. He is the author of The Neighbor Out of Sound (2018) and Jazz Talmud (2012). His jazz-klezmer-poetry record Hermeneutic Stomp was released by the Blue Thread Music in 2013.

Jake Marmer is Tablet’s poetry critic. He is the author of Cosmic Diaspora (2020), The Neighbor Out of Sound (2018) and Jazz Talmud (2012). He has also released two jazz-klezmer-poetry records: Purple Tentacles of Thought and Desire (2020, with Cosmic Diaspora Trio), and Hermeneutic Stomp (2013).