The Great American Jew

We don’t make ’em like we used to

When he was 15, my father built a telescope out of cardboard tubing and porthole glass, lugged it to the roof of his apartment building in Forest Hills, and spent most of the night staring at Jupiter, the rings of Saturn, and the Milky Way. This was in 1956. For decades, the telescope went wherever he did—to Syracuse for medical school; to Boston for his psychiatric residency; to our garage in Southern California, where I was born and where the telescope resided, squeezed between dusty suitcases and bookshelves and 10-speed bicycles. Until a few years ago, when it disappeared.

My father was unique in many ways, but in this way—his curiosity, his capacious appetites—he was very much of a type: New York, postwar, Jewish, energetic, brimming with confidence (in himself, in the future), but tempered by an ageless wisdom that could be traced from the shtetl to Queens Boulevard, a fundamental awareness of inescapable darkness and violence that came from growing up in the echo of disaster. There was the disaster of the recent past—the Depression, the war, the Shoah. And there was the possibility of disaster right now: a job loss, a heart attack.

This type was central to the Jewish American experience, and it stretched across the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st. It had its many foibles—it could be short-tempered and brusque, and, like all types, its apprehension of other peoples and places was colored by its own limited interaction with the world. It was hardly the only type, it had no female analogue—blame that on misogyny—and it was a generalization, all of which are imprecise. But it was part of who we were, and what the Jews (and America) had achieved. The Jewish doctor, Ed Koch, A.M. Rosenthal, Alan Arkin, Chuck Schumer, Michael Bloomberg, Ted Kramer, Moses Herzog, and Nathan Zuckerman are, or were, all shades of this character. Buoyant, irritable, smart, perspicacious, pushy (but not in a conniving way, in a way that reflected one’s sure-footedness). It was an archetype that Jews knew and admired and blew up at and resented and loved. The great American Jew.

Now, this old type is being eclipsed by another type—less capacious, stripped of any youthful enthusiasms. This new type intuits that the edifice upon which postwar America once resided has frayed, that the old assurances are not so durable. He thinks less about the infinite possibilities of a vast and knowable universe and more about the smallness of life. He is cynical. He does whatever he thinks necessary to protect his turf or acquire a little more. He is scared and unsure of who he should be, and his fears and insecurities are projected onto, wrapped up in, his thoughts about the Jewish state. It is the Jewish state’s unavoidable Jewishness, its flagrant disregard for the unpopularity of the Jew qua Jew—and the awkwardness that an uninhibited Jewishness can impose on non-Jews—that so rattles this new Jewish type.

The right-wing iteration of this new figure embraces the Jewish state. He derives from it a sense of purpose, a direction, a vision. He feels like a battalion commander in his very own, imaginary IDF. Alas, he wants from Israel something Israel cannot deliver: the strength to be his own man. The strength to be a Jew in a non-Jewish world, just as Israel is a Jewish country in a world of non-Jewish countries. In Hebrew school, he was the dumb one. The bruiser. With thick digits. He wasn’t actually dumb, but he wasn’t bookish. He identified bookishness with feebleness, and he always admired Israel, because Israel wasn’t feeble. The promise of the Jewish state was not the return of the Jews to their ancestral homeland. It was about sticking it to the Cossacks, Klansmen, Nazis, Arabs. The squad. It was about being tough, which meant being brutish, gruff. What of it? Israelis were gruff. So was Trump.

He is right, sort of. It was impossible to imagine any of Trump’s predecessors pulling off, say, the Abraham Accords. They were too blind or arrogant, too sensitive to popular opinion. They lacked the slipperiness of the bookie, the would-be Don Corleone. They didn’t know how to get it done. They cared about things like Netflix deals and the Nobel Peace Prize. So spare me all your yammering about Marjorie Taylor Greene and the quote-unquote insurrection. Cause DJT. Got. It. Done.

His left-wing counterpart, meanwhile, hates Israel with an unslakable bloodlust. He says he hates Israel because Israel is an apartheid regime, a colonizer of brown people, a pariah state guilty of ethnic cleansing and genocide. Genocide. He says Israel is an embarrassment to the Jewish people. Really, he means: Israel embarrasses me. We sometimes call these people self-hating or secular or cultural Jews (as if eating the occasional bagel or sprinkling Yiddishisms into the conversation can sustain a religious identity). These are the Jews who think it’s OK for a Jew to get tattooed and who live in trendy neighborhoods in New York and Los Angeles and who are tired of being freighted with the yoke of otherness. (One feels for them.) These are the man-bunned, critical-theory Jews, the BDS and #BLM Jews, the Jews, like Lev Bronstein, aka Leon Trotsky, who have complicated relationships with their fathers, the Jews who have internalized two millennia of antisemitism. Just as the early Zionist believed that if he embraced socialism while pretending he wasn’t Jewish, everyone would forget he was a Jew, this new Jew envelops himself in the lingo of intersectionality while eschewing Zionism with the hope that everyone would forget—wait!—that he’s still a Jew. Alas, he hasn’t read his Malamud. One cannot shed one’s Jewishness. Any attempt to do so is among the most Jewish things one can do.

These two characters—the lionizer and vilifier of Israel—are just two sides of the same type: the alienated Jew.

The alienated Jew is not actually a new type. He is a very old type who has resurfaced after a long slumber, weaving this way through the Archimedean spiral of Jewish history. He is the Jew who has been dislodged from his tradition, the ritual, the scripture, the rhythms and wailings and wisdoms of his people. A type but never the type. The type, the dominant persona, was thoughtful, acerbic, wandering, full of hope. What else could one be?

He’d already found his home. The great American Jew was the Jew who, for a time, had transcended his nomadic past. He was as patriotic an American as there ever was.

This dominant type assumed many looks and tongues and permutations. He was scattered across ancient deserts and forests and farmlands and cobblestoned cities and teeming bazaars and the Pale and the ghetto and the steamships ferrying the penniless past Fort Tompkins toward the New Jerusalem. He was the predecessor of the great, postwar, New York Jew—the Jew I always knew and loved and feared, the Jew who found his place in the universe in the canyons of the city: Manhattan, the Island, Jones Beach, the Catskills. He loved Israel. Visited it. Believed in it. Defended it passionately. (The first time my father landed at Ben-Gurion, he welled up.) But he wasn’t of Israel. He would say that his fate was bound up with it, but it wasn’t exactly. He’d already found his home. The great American Jew was the Jew who, for a time, had transcended his nomadic past. He was as patriotic an American as there ever was.

But now everything is fluid. The previous order, the norms and institutions that defined the postwar era and stretched into the post-Cold War denouement, is crumbling. We feel as if we are at sea—lurching for something just out of reach. The GOP base hankers for some prelapsarian America that never was. Our president—kindly, avuncular, not especially deep—wants only to rewind to early November 2016. Most of us are vaguely aware that something has been wrong with the country for a long time, but we tend to blame our queasiness on proximate disruptions: Trump, COVID-19, the lockdown, racial strife, social media. All that is more effect than cause. It doesn’t tell us how we got here. We got here because of big, historical forces that stretch back several decades or more: shifting geopolitics, globalization, the emergence of a new political consciousness. For a long time, we have felt the plates coming unhinged. Now, they are, and everything feels uncertain, including America’s compact with its Jews.

This uncertainty bears down on us from the right and left, both of which have been co-opted by their respective, repugnant identitarians. No—of course, it’s not Badenheim 1939. But the old magnanimity has been eclipsed by a strange wobbliness, and we can feel the walls around us buckling. Just so. We can imagine both major parties dispensing with their Jews—the Trumpkins succumbing to their darkest conspiracy theories; the wokeists succumbing to theirs. We can imagine, for the first time, the e pluribus unum dissolving into a thousand warring ethnic-racial-religious factions, and we know that, when it does, the Jews will suffer, and it won’t matter how many moguls, senators, Supreme Court justices, movie producers or university presidents are in our corner. We know it will be wise to avoid being too Jewish.

The alienated Jew knows this better than anyone else. He who is adept at cozying up, camouflaging, parroting. He who has a dim view of himself and his faith. He who has an even darker view of the American experiment, who thinks that America is a vessel, temporary lodging, that it is run by oligarchs and manipulators of currency and opinion. He who plays along or guffaws at the mention of American exceptionalism. The alienated Jew glances with disdain at the old type—dying or dead, hopeless, a relic. He imagines the great American Jew naive, weak, febrile, racist, cis, patriarchal, white ... The Alienated Jew thinks, Your moment is over. He imagines himself ascending, and he is, in a way, but really, he’s crouching. Eyes darting. Looking for predators. His world must be soldiered through. His world is microscopic.

A few months before the end, I went looking for my father’s telescope in my parents’ garage but couldn’t find it. I couldn’t believe they’d lost it. Had they given it away? My mother didn’t recall. At night, I fell asleep wondering: Where was the telescope right now? Had it been stored somewhere? Or lost? Melted down or crushed or left on a sidewalk or in an attic or the back of a U-Haul? Was someone peering through it at this very moment? The night before my father died, I remembered looking at him in his gray, metal hospital bed and wondering who was staring at Jupiter right now with the telescope he had built 65 years before, in Queens, in his bedroom. I wondered if the disappearance of the scope, which I had never cared about that much but now seemed to me to be infused with magical powers, was a metaphor.

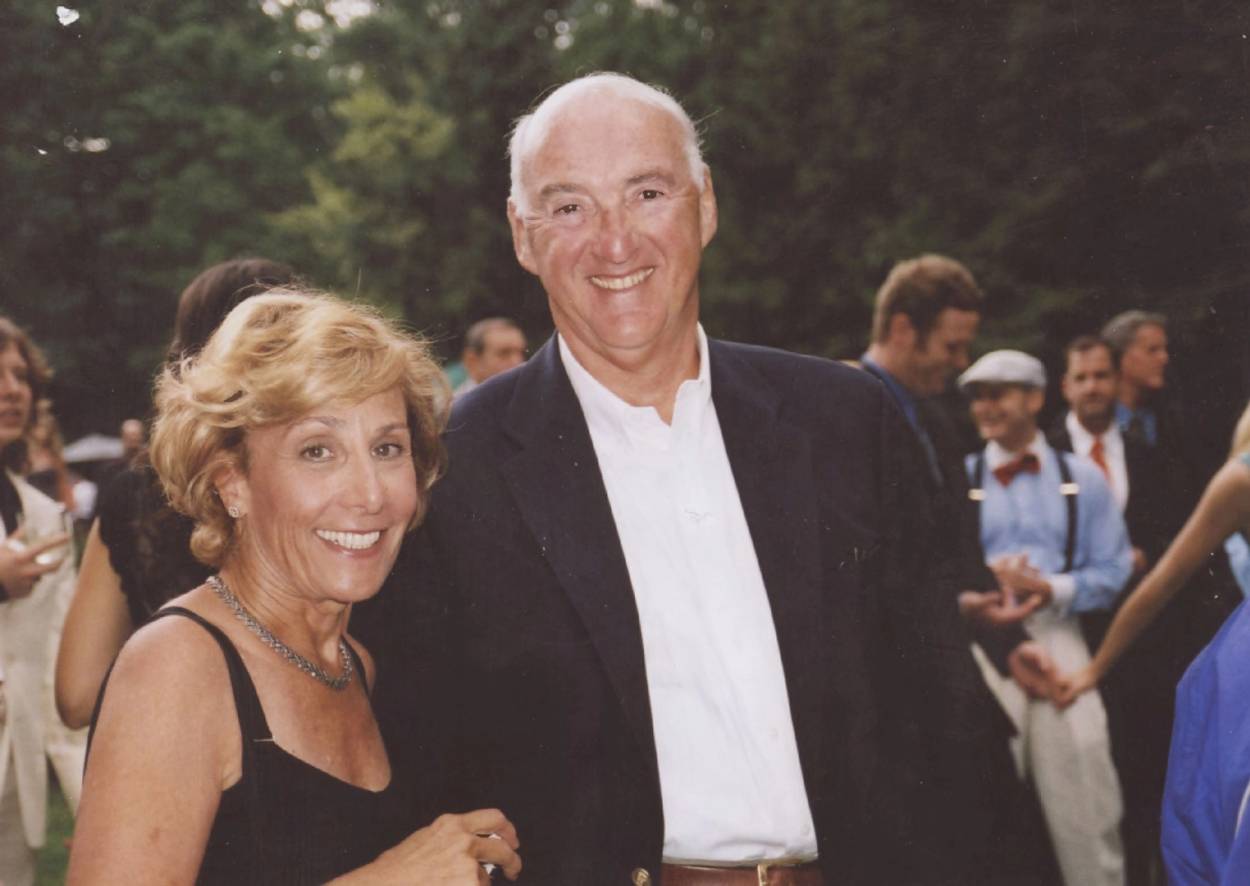

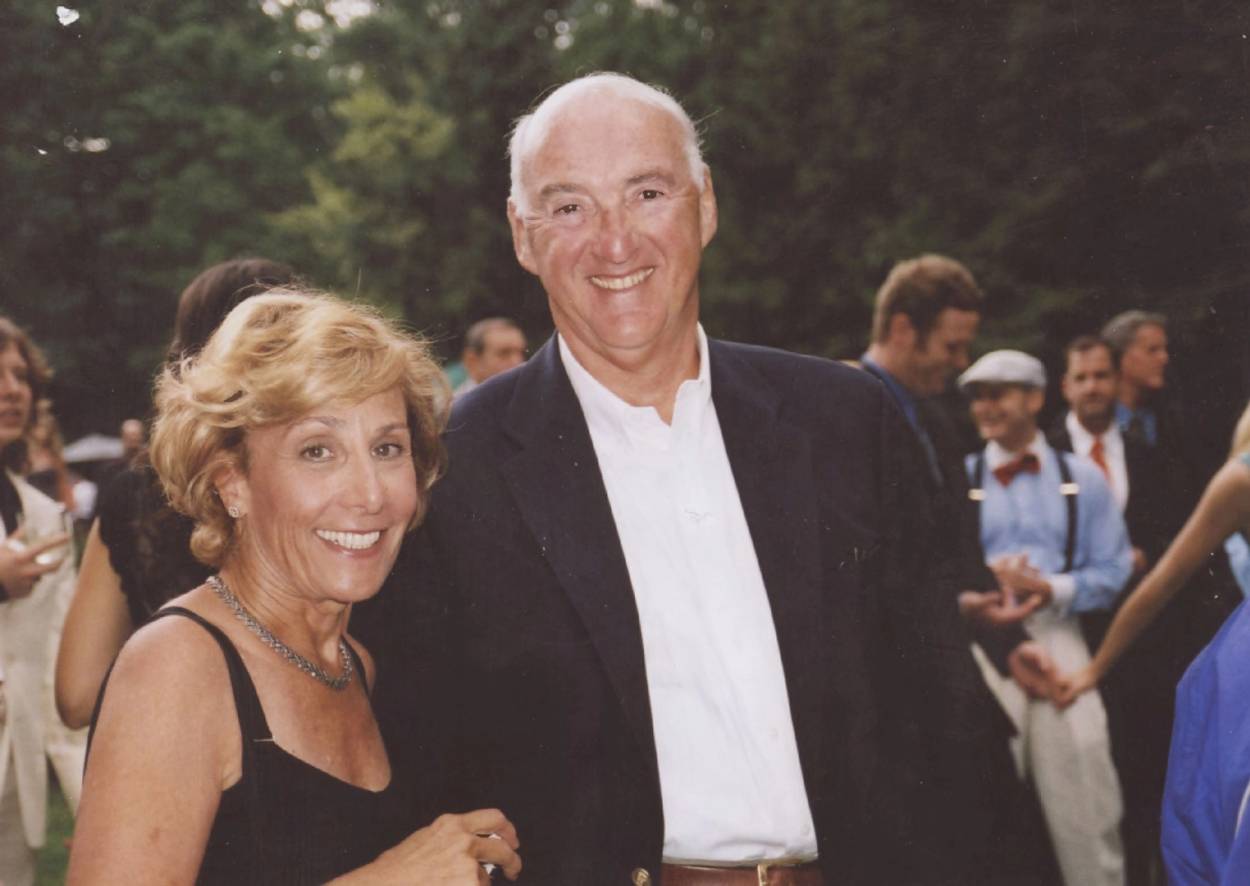

The night before my father died, the three of us gathered around his hospital bed and told stories, and for a few hours we lulled ourselves into forgetting what was about to happen. The hospital bed was in the corner of my parents’ bedroom, in the house, in Manhattan Beach. By then, we were giving him morphine on the hour, and his eyes were closed, and the period between each breath seemed to expand as the night unfolded, as each inhalation and exhalation became a little less perceptible. He pushed on. Once or twice I thought, When will this be over? and then, When this is over, you’ll feel guilty for having wondered when it will be over. The bedroom was littered with the detritus of the nearly dead: an oxygen tank, oxygen tubes, syringes, bottles of medication, instructions from the hospice nurse that had been Scotch taped to the rolling end table. My mother held my father’s hand. My sister made tea. I sat on the upholstered bench at the base of my mother’s bed and stared at the photographs of my parents on my mother’s dresser—at my sister’s graduation, at someone’s bar mitzvah, in front of a wall of books in the basement of my parents’ second home, in Edgartown. My father always looked the same: beaming, suntanned, cleanshaven, with a blue blazer on. A little after 2, I said to my mother, “Do you have any idea where the telescope went?”

The night after he passed away, I had a dream about a conversation we had 22 years ago. I was in my apartment, in Hyde Park, in Chicago. He was at home, in Los Angeles. He mentioned a paper he’d written, on the philosophy of symbolic forms, after his mother died. She’d died a few days after John F. Kennedy. In the dream, I imagined floating across this cosmic axis of space and time, from 1956 to 1963 to the late ’90s to right now, and back again. I remembered my father laughing at something I said, and I remembered him saying my name. It had been four years since he’d last said my name. He was exceedingly good at explaining complicated ideas, and his tendency was to connect things, to see the beautiful webs that bound everything together. It was possible, in those moments, to make out the faraway borders of the known universe, to understand how all the ideas and deliberations and outbursts of artistic genius fit together inside the sprawling, undulating tapestry, and it was exhilarating, and it could make you feel a little inebriated. But now his voice was receding, and I was staring at an amorphous dark, and everything seemed to sprawl, unwind, bleed, devolve into a terrible kaleidoscope of galaxies and conundrums that resided outside his knowledge. In the quiet of the early morning, in the dreary, purplish in between, I tried to imagine what came next, and I imagined my father, always undeterred, saying, That’s it. Keep going. Keep going.

Peter Savodnik is the author of The Interloper: Lee Harvey Oswald Inside the Soviet Union. He writes for Vanity Fair, among other publications. He can be found on Twitter @petersavodnik.