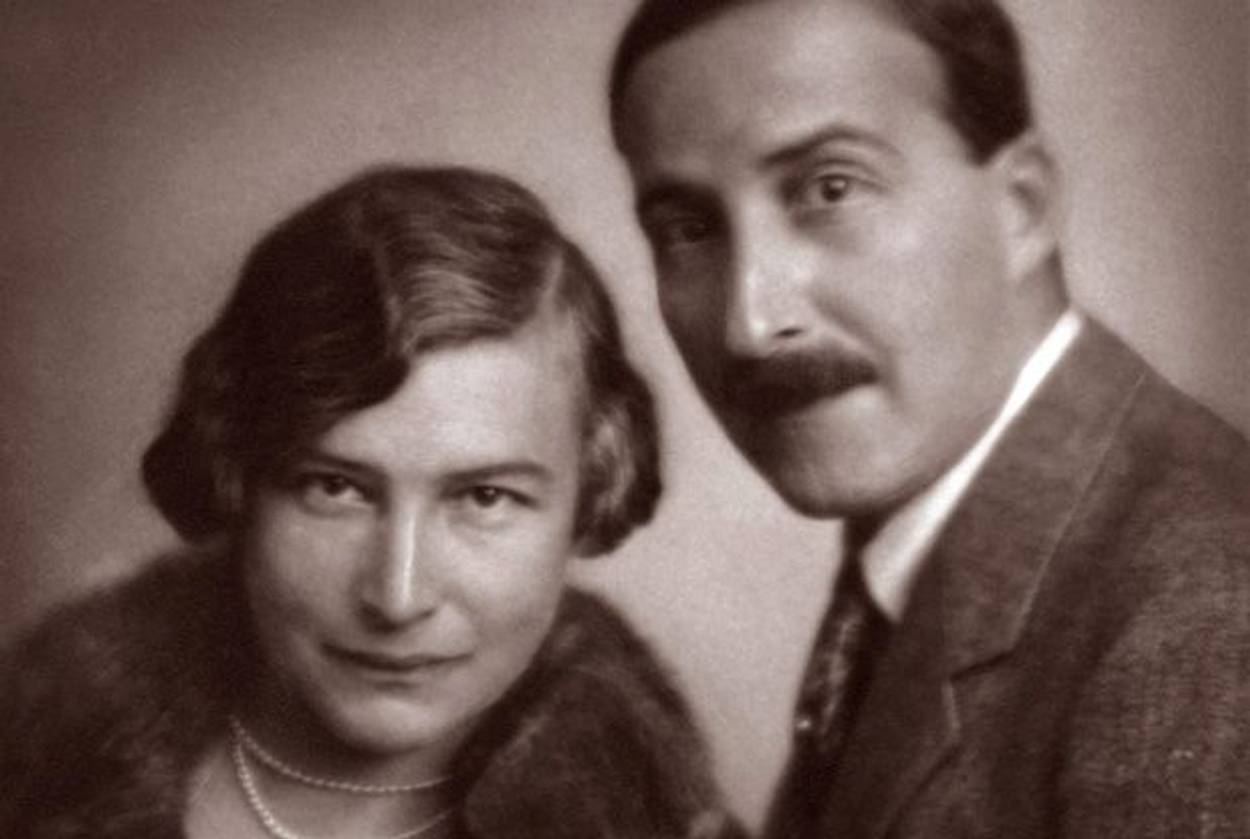

The Jewish Writer’s Dream Wife

Why I published Friderike Burger’s memoir of her service as femme de l’artiste to Stefan Zweig

Tolstoy had Sofya; Meyer Schapiro had Lillian; Amos Oz has his wife and his daughter. Almost every male author I can think of has had an (unheralded, unpaid) assistant in the family whose duties included reading, researching, transcribing, typing, corresponding, and editing for his genius. (Female authors less frequently.) But few couples have had as complicated and even posthumous a relationship as Friderike Burger and Stefan Zweig, the Austrian Jewish writer who was and continues to be one of the most widely translated German-language authors in the world.

Both Zweigs were born in the early 1880s, products of the Habsburg Monarchy. Both were secular Viennese Jews (Friderike converted to Catholicism in her twenties) who lived through World War I and its chaotic aftermath in Austria. They built a house in Salzburg known as “the Villa in Europe” where Zweig wrote many of his most popular works until the rise of Nazism. The house was searched, the books were burned, and the Zweigs were forced into emigration. They divorced in 1938, and Zweig married Lotte Altmann, the young secretary Friderike had hired for him in London. But the couple remained close. Both fled Europe and wound up, in their early sixties, in New York. Friderike had the resilience to create a new life there, but Stefan and Lotte moved to Petropolis, Brazil, where they committed suicide in 1942. Friderike’s memoir is, I think, a rare account of two 20th-century Jewish writers, their liaison, marriage, divorce, and continuing friendship, from a surviving ex-wife’s point of view.

***

Friderike Maria Burger was born into two Jewish families, the Burgers and the Feigls, on Dec. 4, 1882. She was the exact contemporary of Ida Bauer (whom we know as Freud’s case study “Dora”) and a generation younger than Bertha Pappenheim (Freud and Josef Breuer’s case study “Anna O”). After attending the University of Vienna as one of the first few women permitted to take degrees, Friderike married a civil servant named Felix Edler von Winternitz. She published a few newspaper articles but soon abandoned her “hobby of writing” to supplement the family income by teaching French and history.

She was 26 when she first exchanged glances with Stefan Zweig in a Viennese wine garden in 1908. “I shall tell you about this romance as if I were an outsider, thereby overcoming my reluctance to reveal my personal life,” she writes. Her husband was taking a rest cure at a nearby sanatorium; her baby daughter was at home with her nurse. Friderike was out with friends on that summer night. Her marriage was only two years old but tepid. She was less attached to her spouse than she was to his father.

Stefan was 27, an up-and-coming poet and playwright. His father owned a textile factory in northern Bohemia; his mother came from a banking family; his older brother ran the family business, leaving Stefan free to write without worrying about an income.

No words were exchanged but Friderike didn’t forget him. Four years later, when the two again exchanged glances in a garden restaurant, she was then 30, mother to a second daughter, and even more restive in her marriage. Stefan was 31, a celebrated Viennese poet and debonair man-about-Europe. She wrote him a letter.

They began the kind of liaison that Arthur Schnitzler and Zweig himself so often dramatized for their Central European audience. Letters. Visits. She got a gig to review one of his plays in Germany where the couple perhaps consummated their relationship. Then she went away to the Tyrolian Alps with her ailing daughter; he traveled to Paris to work. Neither evinced any jealousy on her account. In his own classic memoir, The World of Yesterday, Stefan makes no mentions of his private life. But Friderike tells us that Stefan argued for her eventual divorce and the consolidation of their households. He viewed her daughters and professional life as assets that would prevent her from making too many demands on his time.

‘The most important thing was to maintain an atmosphere of peace, to dig trenches around his spiritual castle.’

Friderike obtained a divorce that was kept secret from her own mother and her father-in-law. She worked out separate financial arrangements with her husband and with Zweig. For most of World War I, they shared a compound outside Vienna where they lived in two pavilions, enabling the by-now internationally celebrated author to work without interruption while enjoying the benefits of Friderike’s housekeeping. He was the artist; she the devoted, capable, practical helpmeet. She translated and edited as well as managing their social calendar.

“As guardian of his inner world I was to keep the outer world away, pregnant as it always was with disturbances,” she writes. “Therefore—a fact but seldom openly confessed—I was to have no world of my own, no work of my own that might possibly deflect me from my watch. The circle was widely extended but I had to stay within it.”

By 1917, Zweig entrusted Friderike to purchase a home in his name. He found that living in Vienna distracted him from work, and the couple decided to buy a romantic ruin glimpsed while visiting Salzburg together. It was a 17th-century hunting lodge with rudimentary plumbing and no electricity. Located on a hilltop called the Kapuzinerberg because of its proximity to a Capuchin monastery, it was also barely accessible. It became Friderike’s project to oversee the renovation during a time of scarce building materials and workmen, fluctuating currency, and the chaos during the last year of the world war.

In 1920, the now-married couple moved in and began to receive literary luminaries such as Romain Rolland and Joseph Roth and musicians such as Richard Strauss, Arturo Toscanini, and Bruno Walter, who had been engaged by the annual Salzburg summer festival. During the next 13 years, Zweig produced some 200,000 pages, or 50 individual pieces of work there, with a wife who served as first reader and editor.

“I could lend him a hand in various ways,” she writes, “besides showing my warmest interest in his work, and occasionally suggesting new themes. But the most important thing of all was to maintain an atmosphere of peace, to dig trenches around his spiritual castle. He refused to let me do his typing or take shorthand dictation. I could spend my time to better purpose: by helping in research, translating quotations from foreign languages, reading books sent to him, making excerpts from them, and finally writing letters of acknowledgment in his name.”

Friderike raised her two daughters with little participation from Stefan. One can only imagine the complications for two adolescent girls and their mother in a home where their benefactor’s insistence on silence was the rule. However, the couple’s unusual relationship would survive far more than those family tensions. It withstood the rise of Nazism, with its burning of Zweig’s books, a traumatic search of the Kapuzinerberg house, and the couple’s sharply differing views about whether to remain in Austria or leave it. After Stefan left Salzburg for good, Friderike continued in her many roles as helpmeet, even after they divorced and Stefan remarried.

Her story, with its colorful cast of characters and international backdrop, is extraordinary in itself. But what kept me reading was her detailed reporting of marital life with the famous writer, reporting that veers from insightful to unabashedly mystical and sentimental. Most of the time, Friderike is crisp, supplying a store of social history in unusual detail. Here she is describing the couple’s involvement in adult education after World War I:

The Socialists, now in power … established promising institutions called “County Educational Courses” intended as forerunners of people’s universities to be founded in all the former Habsburg Crownlands. Their underlying idea was to lure the unemployed, most of whom were discharged soldiers, away from the streets. … The men were supposed to use their leisure time in pursuit of “culture.” Schoolrooms were opened up for these courses, and the Salzburg intellectuals asked to function as teachers. … Stefan gave a course on literature. Those desiring to emigrate were especially interested in foreign languages. My state diploma enabled me to give a French course for beginners, in which seventy pupils of the most diverse ages were enrolled.

At other times Friderike falls back on the clichés of a romance author: “I, on the other hand, had always been open to the unpredictable effects of predestination. Strange incidents, recurring in our union after long intervals, seemed like portents of destiny. And the last link in the chain … was marked by an atmosphere of tragedy and inevitability.”

She also tracks and describes what contemporary readers might recognize as her husband’s manic depression: “Sadness and laughter alternated as speedily in my husband as in a little child. But it was different when Stefan, assailed by some serious crisis, used any and every occasion as a pretext for his rage. After it was all over, he could not remember what he had said or done. But he knew that everyone was helpless in the face of these terrifying attacks. … These crises occurred with increasing frequency during the years of his male climacteric, as the doctor called it.” We cringe when she paints a wildly idealized portrait of “the beloved poet” or invokes her “involuntary and indissoluble affinity” with him.

Friderike addresses divorce head on. In a chapter titled “The House Breaks Up,” she writes: “Friend and foe alike will judge harshly a man of almost sixty who, dissolving his union with a but slightly younger wife, joins himself to a girl his junior by twenty-seven years. … But there existed such an indestructible friendship between me and my mate that intuitive sympathy with his feelings, never wholly undermined, survived all the conflicts.”

It’s easy to see why her brother-in-law Alfred Zweig (who lived on Central Park West in New York City until 1977) found her phony and her memoir a document of life with Zweig as she had wanted it to be rather than what it was. Not only, in his view, did she appropriate the role of author’s widow (“the companion who was at Stefan’s side during the most productive years of his life”) but she included in this memoir what she had heard from Stefan of the Zweigs’ family life before she entered it.

I suspect that Friderike’s self-identification as an Austrian Catholic must have irked Alfred profoundly, as it seems to have irked Stefan. Married to Stefan Zweig (first published in 1946) highlights Stefan’s dislike of Christmas celebrations. Friderike explains it away as a consequence of childhood jealousy when his parents’ servants received gifts while their children did not. Her embrace of Christianity as well as of Austria was delusional after 1933, yet Friderike exults that Zweig’s mother “never objected to her sons’ marriage to women of other faiths,” and asks, “Had not the [Christmas] tree been universally adopted by non-gentile families?”

Despite these flaws, I find Friderike’s memoir an invaluable document. In The World of Yesterday, Stefan aimed to write a memoir of his generation; in Married to Stefan Zweig, Friderike was interested in portraying the man, filling in details in her memoir that Stefan left out of his. Literary historians as well as Zweig’s contemporaries have had questions about Zweig’s sexuality. Anthony Heilbut, author of a comprehensive biography of Thomas Mann, contends that “Zweig shared Mann’s quiet but intense adoration of young men. Interviewed in the 1990s, German émigrés who were living in Brazil in 1942 remembered the older man as obviously attracted to them. Words were unnecessary; as in Letter from an Unknown Woman, one glance told the story.”

Although Friderike does not provide a clear answer to the question of her ex-husband’s sexuality, sex was clearly not the core of their long relationship. In the end, she too fled Austria through France, across the Pyrenees to America. She was able to create a new independent life for herself in New York, where she arrived in 1940 with her two grown daughters and their husbands.

In Austria, she had helped found a chapter of the International Women’s League for Peace. In New York City, in 1943, she co-founded the Writers Service Center, a literary agency, clearing-house, and all-around refuge for European refugees and exiles, and the American-European Friendship Association, a cultural center. Two years later, at the age of 62, she moved to a house overlooking Long Island Sound in Connecticut where she spent her last decades writing, engaged in memorializing her husband, and supporting various progressive social causes. She died on Jan. 18, 1971, at the age of 88.

Helen Epstein is the author of the memoirsChildren of the Holocaust andWhere She Came From: A Daughter’s Search for her Mother’s History.