Like all complex works of art, Olivier Assayas’ eponymous film about the life and times of the Venezuelan-born terrorist entrepreneur Illich Ramírez Sánchez—known by his nom de guerre, Carlos—asks us to hold several sets of contradictory ideas and emotions in our head as we watch: Terrorism can appear thrilling and glamorous, yet, like much of war, most of it is also deeply boring and banal; in the attempt to become heroes and lead actors in the movie script of our own lives, we often end up doing dirty work for people we may never meet face to face, reduced to extras in their production, chained when we thought we were “sovereign” or fighting for the freedom of others, ultimately another disposable tool.

Another set of contradictory ideas and perhaps the most important and difficult to grasp, and one that constitutes the film’s signature achievement, is the way in which it both shows how we inhabit a world in which most of us consume politics and “political content” in the same fashion that we consume clothes, food, cars, and all the other objects or “goods” of modern mass society, and that this process of consumption renders our politics increasingly surreal, spectacular, and spectral. Yet, what is too often forgotten in such blithe statements about the “unreality” of everyday life, or the commonly expressed sentiment that “all politics is global”—which has eclipsed the cliché that “all politics is local”—is that the surrealism of our politics, the politics of the image or of optics, of branding and messaging, still has very real consequences and outcomes: in blood, in the terrible waste of human life, and in ways that distort and disrupt human flourishing all over our planet. We live in a world where a 72-year-old man can go out and stab a 6-year-old boy and his mother because of something he watched on the news that happened tens of thousands of miles away, shouting as he did so, “You Muslims must die.” Several days later, a couple of anti-Zionist-definitely-not-antisemitic Germans threw Molotov cocktails at a synagogue. Both of these attacks, one in suburban Illinois, the other in Berlin, directly resulted from an earlier terrorist attack against Jews in Israel, streamed across the world, in some cases livestreamed through the social media accounts of the victims. These spontaneous attacks, carried out without need for orders or a chain of command, are not a result of the “law of the jungle” but of the supersaturated advanced civilization of spectacle.

Most of us consume politics and ‘political content’ in the same fashion that we consume clothes, food, cars, and all the other objects or ‘goods’ of modern mass society, and this process of consumption renders our politics increasingly surreal, spectacular, and spectral.

Carlos, the film, was released in 2010, in two cut-down versions for theatrical release in Europe and in a full-length miniseries version that runs about 5 hours-plus. It’s clear now that the film occupies a hinge point: It looks back fondly at the still awkward age of early television news and the golden age of New Wave cinema as prehistories of the more seamless but more contested mediasphere emerging in the wake of 9/11 and the U.S. invasion of Iraq, the Second Intifada and Lebanese war, while facing forward to the massively always-online world we live in today where viral terror now seeps through screens and smartphones.

Olivier Assayas was, in many respects, perfectly poised to grasp both the history of spectacular media and of its political dimension when he chose to make the film. Influenced, as he’s said, by the French situationist theorist Guy Debord and the anti-totalitarian writings of George Orwell, he’d begun his career as a film critic for Cahiers du Cinéma, the great incubator of the French New Wave and later its custodian. In a sense, Assayas has become that tradition’s belated inheritor.

Assayas’ breakthrough film Irma Vep (1996) was a meta-drama about an aging director’s attempt to remake an old French silent film series about—yes—a gang of international terrorists and spies known as “the vampires,” but this time updated with the techniques of contemporary Hong Kong action cinema à la française. The premise was absurdist. Vep was a comedy but also a commentary on the way cinema both arouses and fails to live up to desires, a film about an ultimately unmakeable or just unmade film. Assayas filmed dead-on realist scenes about how a movie-sausage is made: well-meaning but wrong-headed costume designers, tetchy producers, lazy cameraman, and hapless set designers. Vep was a love letter to cinema and also to Assayas’ chosen lead, Maggie Cheung, who rose out of the ashes of the failed film-within-the-film as an international star.

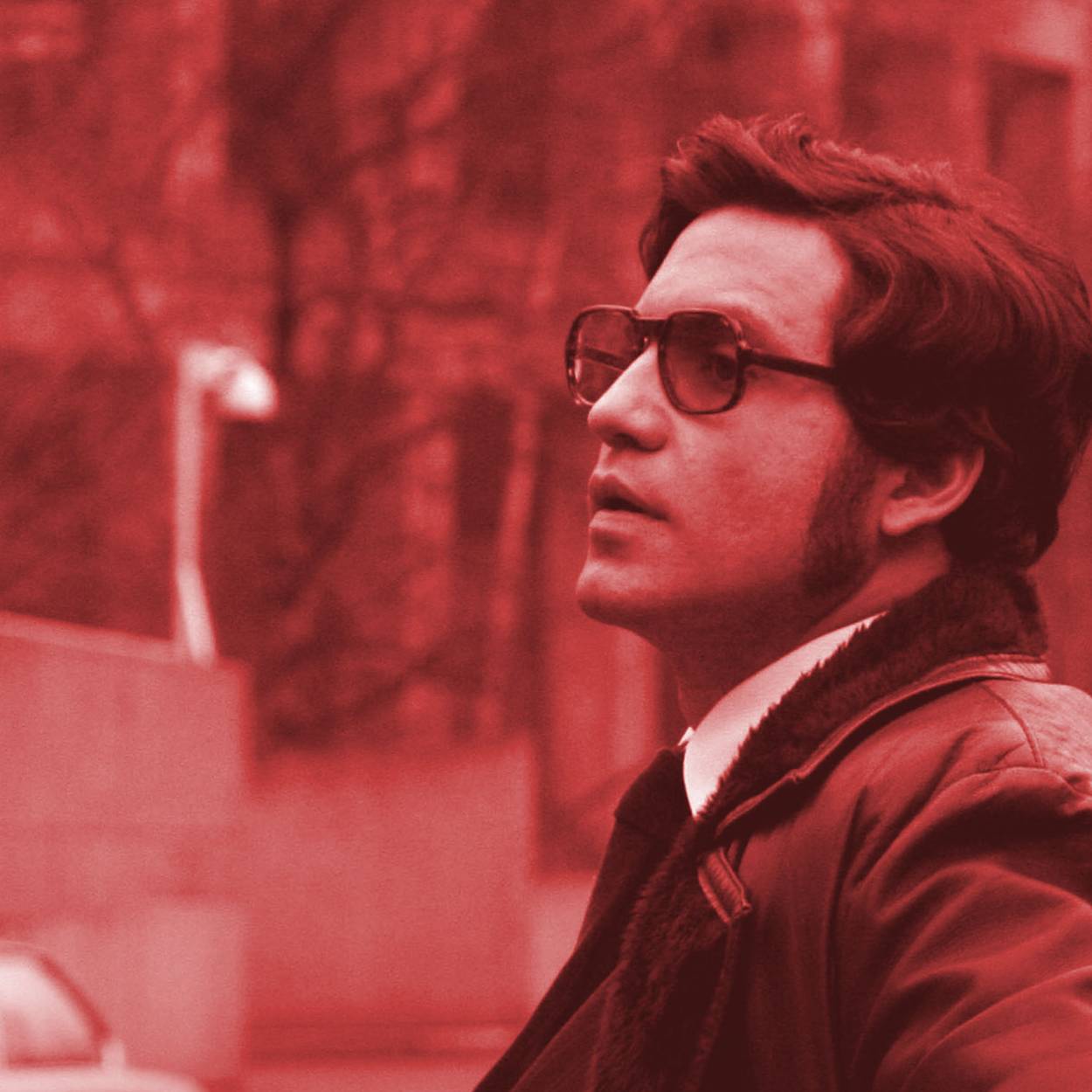

Where Irma Vep takes gimlet-eyed, satirical, behind-the-scenes realism and turns it back into romanticism, Carlos works in precisely the opposite way. Here the full machinery of cinematic illusion is unleashed to produce a drama that seemingly wants to demystify. There are the usual tropes of international thrillers: car bombs, assassinations, so many shots of people getting in and out of cars, suspenseful crosscutting, spectacular location staging in remote desert hideaways and palaces, perfectly art-directed period apartments, plus a healthy helping of hot sex. And yet, something is missing. At its core the film is a cold look at a very cold man, a sociopath who thought he could climb to fame and international stardom over the dead bodies of his victims, using the name of “the Palestinian cause” that he claimed to serve despite an avowed hatred of Arabs and almost no interest in actual living Palestinians.

Carlos is a film about a man who mistakes his life for a movie. And like movies, the life requires a lot of money and heavy equipment to get made, as well as endless meetings, browbeating of friends, manipulation of lovers, and the cooperation, also, of various obliging authorities to sign off. In Carlos’ case these authorities included weakened French, Austrian, and West German governments, all-too-ready to play along and negotiate, along with Eastern bloc regimes and nascent Baath party dictators in Iraq and Syria looking for chaos agents.

All of this produces a queasy feeling that one is watching an entertainment turned against itself, a massive spectacle that takes aim at the ideologies and pathologies that would lead an otherwise intelligent, capable, if also unremarkable young man, to grant himself the power to shape world events single-handedly or with the aid of small cadres, along with the power of life and death over others. The film suggests that the same impulses that made possible Carlos’ semisuccessful hostage-taking of the OPEC conference in Vienna, in 1975, are what keep us glued to our seats watching a restaging of this same event intercut with period footage.

This approach isn’t without risks. Carlos’ “critical perspective” or in-built irony often runs up against the resistance inherent in the genre. Just as it’s impossible to make an ironic rock ’n’ roll anthem, as Bruce Springsteen and Neil Young discovered when politicians started using Born in the USA and Keep on Rocking in the Free World as jingoistic crowd pleasers at rallies, so Carlos too has moments where the coolness of the form—its mobster-chic style with its parade of luxury automobiles, and punk soundtracked shootouts—seduces us anew with the same message it wants to inoculate us against. The same thing happened to Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas, a film everyone remembers for Joe Pesci and not for its anti-mafia message and framing about a man destined to spend the rest of his life in the hopeless exile of a witness protection program.

Yet Carlos as a film is also committed to disrupting the myth of Carlos the man. At one key moment, the film pulls back from its focus on our anti-hero to show the mechanics behind a Stasi recording of a meeting with one of Carlos’ key associates. The shot feels unnecessary until we remember that it was only thanks to this overscrupulous Germanic mania for recording absolutely everything that we even know today about the extent of this purported freedom fighter’s complicity with one of the most unfree regimes in human history. There’s also Assayas’ curious tendency to film certain moments, especially the violence, in the cinematic style of the period in which the violence took place. So the color of the blood that pours from the policeman’s neck is 1970’s color stock fake blood, a vivid, artificial splash of red, while a gut-shot comrade barely bleeds at all. Yet such patterned effects play an important role in helping us to see what’s truly on display here—a world of fakes, frauds, liars, narcissists, and “magicians,” or, one might say, true vampires of the human spirit, those who always need fresh blood to keep themselves feeling alive.