Where Hola Meets the Hora

Bandleader Arturo O’Farrill puts a new spin on a Latin-Jewish classic

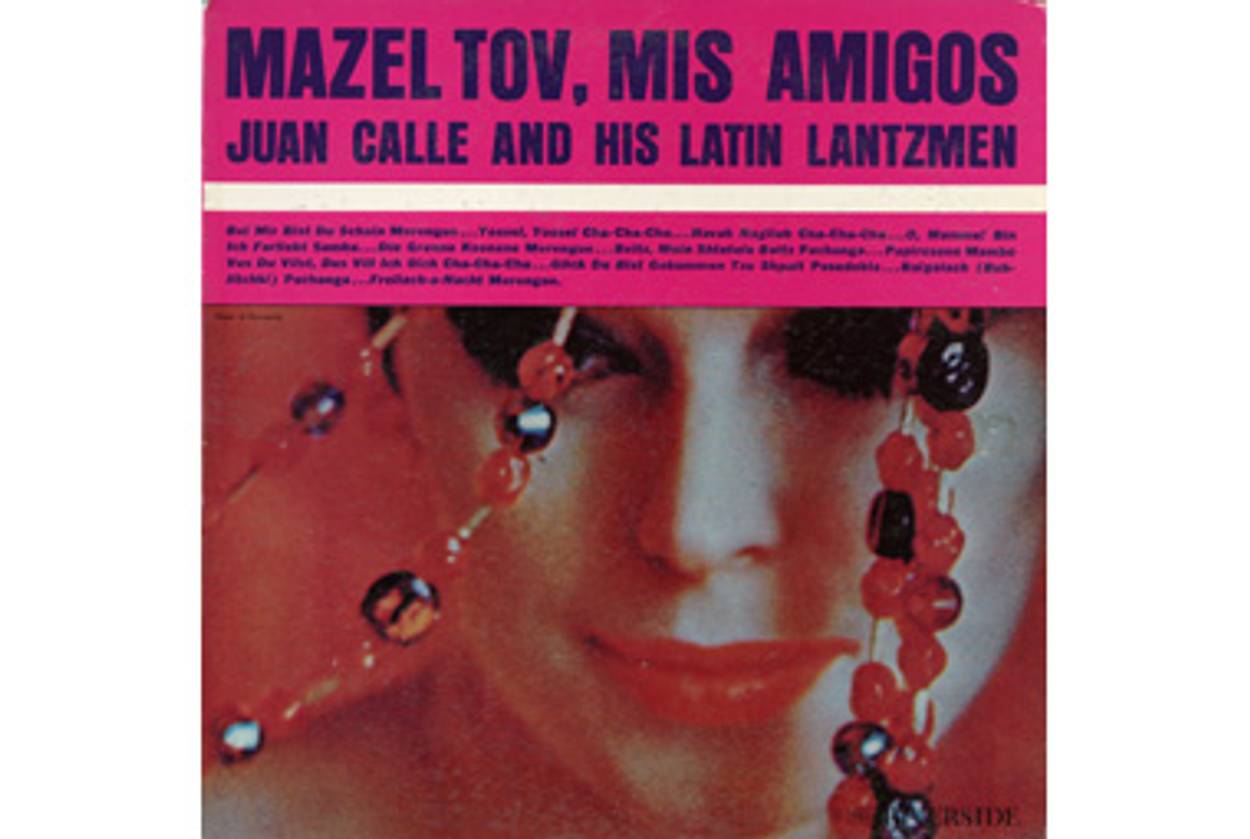

Anyone who’s seen Dirty Dancing is familiar with the relationship between Jews and Latin music, at least among the Catskills set. Of course in the early 1960s, when that movie takes place, the “fad” was on its way out among the youth, as evidenced by heroic dance instructor Johnny mumbling that his sniveling boss “wouldn’t know a new idea if it hit him in the Pachenga.” Now, again, though, the hip kids at the Idelsohn Society for Musical Preservation are bringing back the simpatico combination with their reissue of 1961’s Mazel Tov, Mis Amigos on their label Reboot Stereophonic. The album was marketed as a recording by the fictitiously named Juan Calle and His Latin Lantzmen, which offered Yiddish standards, including “Bei Mir Bist Du Shein” and “Papirossen,” in a Latin dance style. In a twist on the usual tendencies of cultural appropriation, the band was actually made up of Latin and African American jazz stars, including Charlie Palmieri and Doc Cheatham, pretending to be Jews.

To celebrate the release, there will be a one night only performance of the album by Arturo O’Farrill’s Afro-Cuban Sextet next Sunday, August 23, in New York City. The band will be accompanied by guest stars including Jeremiah Lockwood, the Antibalas horns, and Irving Fields, who was one of the pioneers of the Jewish-Latin fusion sound.

“This is a quintessentially perfect New York Latin jazz and Jewish music project,” says O’Farrill. As a kid in Manhattan, “my best friends were Arthur Meyer and Scott Mendel, I grew up going to Brighton Beach to visit their relatives,” he says. “It’s just natural for me to have grown up in an environment where I knew the word schlep.” The Latino element was even more of a no-brainer—he was born in Mexico and his father was Chico O’Farrill, a renowned musician and founder of the Afro-Latin Jazz Orchestra, which Arturo has led since 1999 and which was in residence at Jazz at Lincoln Center from 2002-2007. The relationship between Jewish and Latin music, he says, has a “symbiosis that you can trace directly, historically. In addition, there’s a lot of empathy [between the two cultures] on the issue of alienation.”

When O’Farrill first listened to Mazel Tov, “it seemed like something I’d heard my whole life. When we were teenagers, we used to jam in jazz and funk, and sometimes attach a freilach melody.” But he has a distinctly lighthearted attitude toward what he calls this “musical interchange”: “There was nothing serious about the ‘preservation of society’ in it.”

He has a unique appreciation for the fact that the album’s musical fusion was partly catalyzed by a profit motive. “It’s a spirit of camaraderie and musical experimentation, not without its fair share of obvious marketing desire,” he said with great cheer. “But I think that’s cool, and very intensely funny, that someone at Riverside Records thought, ‘Let’s make a Latin Jewish album. Think how many people will buy it!’”

Although he is thrilled with the work the Idelsohn Society does, says O’Farrill, “The philosophy behind so much institutionalization is backwards: let’s preserve. That wasn’t the idea behind the creation of this album. It was: let’s progress a tradition.”

“When I was in Jazz at Lincoln center, and this may be the reason I’m not there anymore, I wasn’t interested in being a ‘museum band,’ replicating something people did with the spirit of newness when they first did it,” he says. Instead he prefers to ask, “Why did it seem so great in the beginning? Because people took chances.” O’Farrill’s instincts are more at home in a series like Lincoln Center Out of Doors, of which Sunday’s performance will be a part, and for whom, he says, “their guiding light is that rare fleeting magic that takes place when you do something wild.”

O’Farrill doesn’t think there’s anything particularly challenging about the music on Mazel Tov, but he does believe it takes a certain background to be able to make it work: “You have to find people who’ve played their fair share of mambo dances and their fair share of bar mitzvahs.” He says his band fits the bill. He has a particularly star-studded crossover experience on his resume. “I played a birthday party for the president of Movado U.S.—myself, Wynton Marsalis, and Paquito D’Rivera.” The watch honcho’s request from the jazz greats? “Hava Nagila.”

On the album, each track is listed as a pairing between a traditional Yiddish song and a particular Latin musical style, including mambo, cha-cha, and, yes, a pachanga (“Beltz, Mein Shtetele Beltz”). According to O’Farrill, these are relatively proscribed forms, and the renditions on Mazel Tov don’t veer far from the basics. “The depth does not come from the depth of the style,” he says, “it comes from the synchronicity.” Neither are the Yiddish songs particularly profound or meaningfully lyrically, which appeals to O’Farrill’s populist attitude. “Its not the profundity of rabbinical, liturgical singing, it’s from the more accessible end. In that sense it’s beautiful. [They] left the profundity to come from the interchange.” He intends to do the same at the show, at which, he says, “all kinds of madcap mayhem will hopefully take place.”

Hadara Graubart was formerly a writer and editor for Tablet Magazine.

Hadara Graubart was formerly a writer and editor for Tablet Magazine.