First Resorts

The history of the Jewish Catskills before the Borscht Belt was born

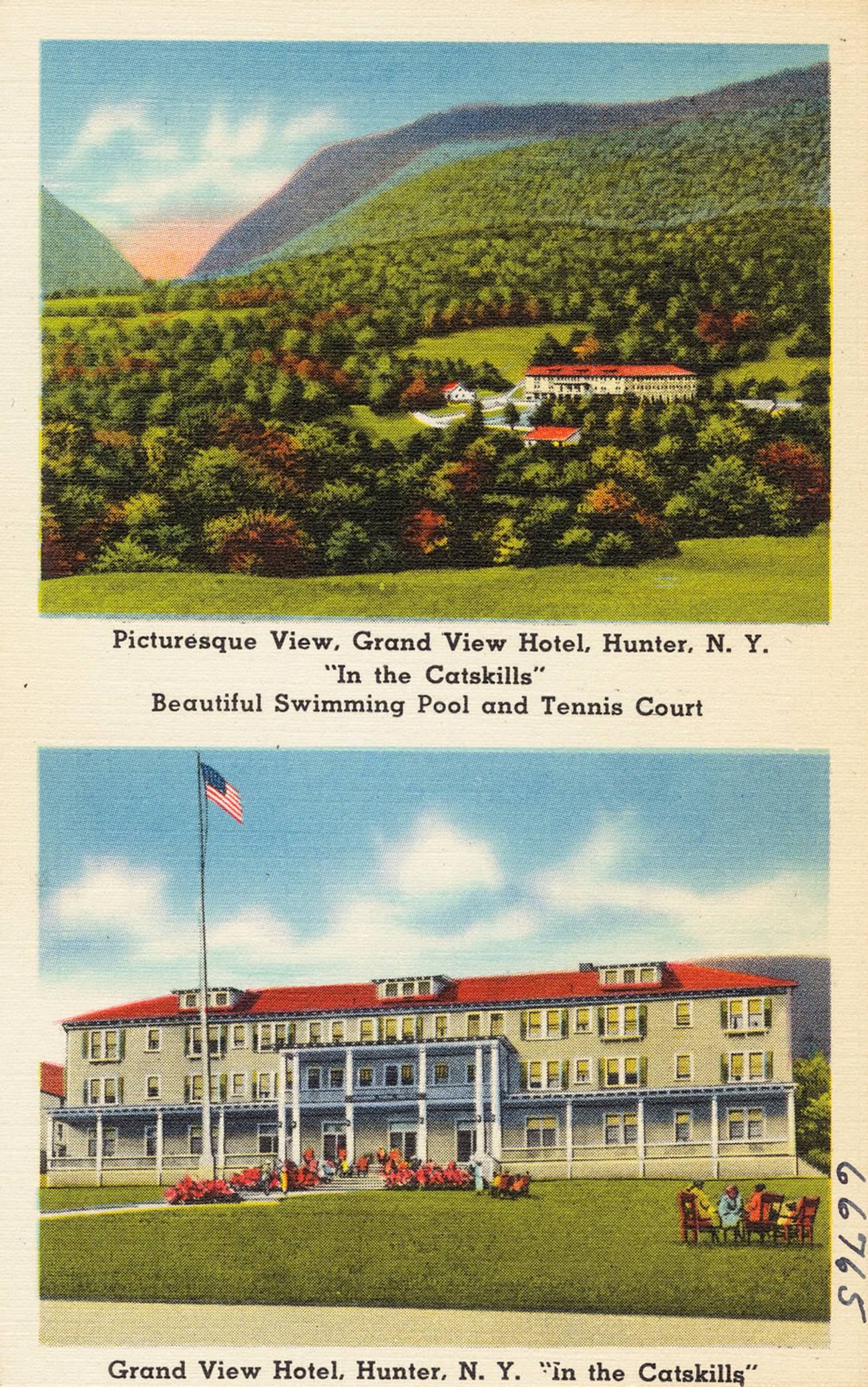

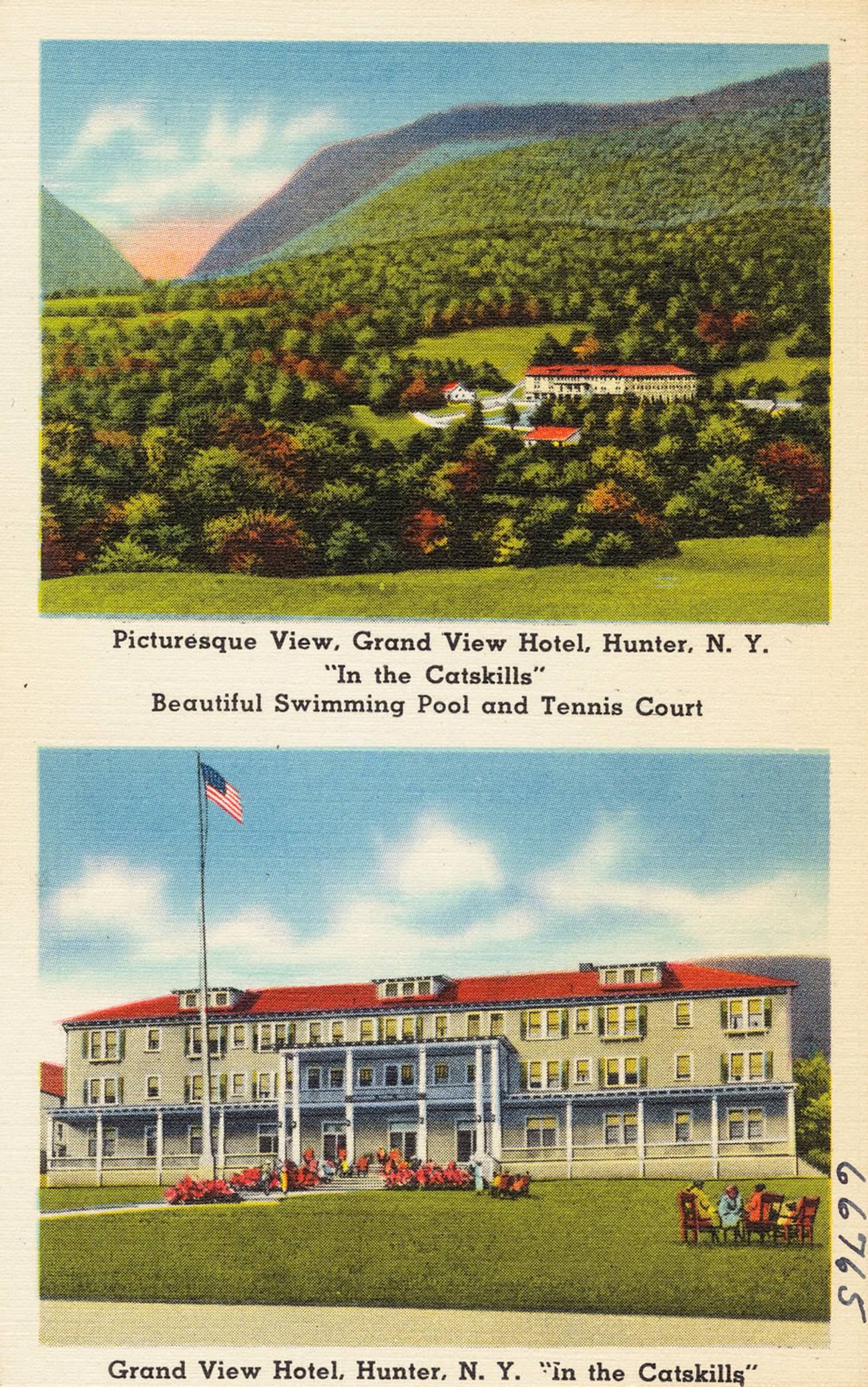

Boston Public Library via Flickr

Boston Public Library via Flickr

Boston Public Library via Flickr

Boston Public Library via Flickr

Long before there was a Concord or a Grossinger’s, there was the Fairmont and the Grand View Hotel. “Never heard of ’em,” you say? That’s because these establishments came into being and then folded their tents before the Catskills became known as the Borscht Belt.

As the self-proclaimed “Leading Jewish Summer Resort of America” and the “First Hebrew Hotel in the Catskills” respectively, the Fairmont and the Grand View belonged to the first generation of vacation venues that catered to a New York Jewish clientele in the years prior to and immediately following WWI. (At the time, its pleasure map also embraced Long Branch and Elberon on the Jersey Shore and Arverne and Far Rockaway in Queens, but that’s another story.)

Their successors are much better known—their names ring a bell—but these sites also deserve their moment in the sun. Far more humble, with fewer amenities—a broad, sunlit porch was apt to be the big draw, not a smoky nightclub—they set in motion a series of expectations that would come to define the Catskills experience over time: the pursuit of pleasure, the celebration of abundance and bounty, the cultivation of appetite rather than the maintenance of restraint. These vacation spots made it possible for American Jews to embrace leisure as an end in itself.

No longer did they have to camouflage a summer vacation as a way station to, say, better health. Instead, summering became the thing to do. So much so that the Hebrew Standard, “America’s leading Jewish family newspaper,” came up with a weekly column of comings and goings in the Catskills and elsewhere, which it dubbed “Summerings.” Not to be outdone, the American Hebrew, in turn, countered with a column all its own, giving it the more high-toned title of “Social Items.” Readers of one or the other—or both—would learn who went where in the Catskills and for how long.

Advertisements touting the merits of one establishment after another filled the pages of these two newspapers, fueling the public’s interest, as did promotional booklets “available upon request” and, later still, tantalizingly colored postcards, eye-catching billboards, and photo albums. Competing with one another for the Jews’ custom, some hotels boasted about their “first class” accommodations, others of their spring-fed water, the “milk from our own cows,” their “unequaled” views, or their private bathrooms and “electric bell system in every room.”

Virtually every summer redoubt declared that the food served several times a day was strictly kosher; as a grace note, many also sang the praises of their Hungarian cuisine. That reference may stump contemporary historians like me, but it meant something back in the day: code for “you’ll not want for something good to eat.” An umbrella term that covered a lot of bases, Hungarian cuisine spoke of quality to some and of quantity to others. It also reassured prospective vacationers that they’d find nothing too exotic on the menu: just the familiar, comforting fare of fruit soup and pot cheese with noodles on the milchik side of the ledger; goulash and veal stew on the fleischik side; and everything well-spiced with caraway, or dill, or poppy seeds.

At first, most Catskills establishments more closely resembled a private home than a public hotel, which, in fact, was how many got their start: as boarding houses that rented out individual rooms for a week or two at relatively low cost to one family at a time. Known in Yiddish as a kuch-aleyn, thanks (or no thanks) to the practice of each family cooking for itself in a communal kitchen, they left a lot to be desired. Mama and papa and kinder would be crammed into one room, which was barely tolerable when the weather was decent and downright intolerable when it was not. Indoor bathrooms didn’t exist, only outdoor privies, and outbursts of “Who drank my milk?!” were a daily occurrence.

Mindful of their property’s limitations, as well as the aspirations of their clientele, proprietors sought to make “improvements” just as soon as they could, all too aware that patrons would kiss the kuch-aleyn goodbye once their wallets expanded. Enter: the hotel. More and more rooms were added to the house until it took on wings; a common kitchen gave way to a dining room that accommodated hundreds of guests at one sitting, every one of them hungrily eyeing the daily mimeographed menu. The roster of available amenities similarly grew by leaps and bounds to encompass golf courses, concrete-and-steel swimming pools, tennis courts, billiard rooms, even ballrooms and, later still, casino-cum-nightclubs.

With no shortage of things to do all day long and into the wee hours, adult vacationers replicated familiar patterns of urban sociability—charitable benefits were thick on the ground, as were opportunities for nursing a cup of tea or coffee—while introducing new ones, such as golf tournaments. Children were kept busy, too, engaging in outdoor sports as well as in masquerades, like the one in 1914 in which Eleanor Markowitz took home first prize for her costume as an ice cream cone, while her brother Victor came in second for dressing as a Hungarian peasant girl.

Perhaps the only aspect of the urban Jewish experience that didn’t carry over to, much less prosper in, the Catskills was synagogue life. Communal gatherings were aplenty, but davening together? No, thanks.

It wasn’t as if there were no synagogues in the area. In the early 1900s, a number of people who owned or rented “cottages” in Tannersville, New York, for instance, established a “pretty little synagogue, spacious enough for its needs, harmonious in its decorations and with large windows nobly open to the ever-changing beauty and glory of the mountains.”

For all its charms, the synagogue barely drew a minyan on Shabbos. Some of the locals begged off, claiming that the building was “inconveniently far away.” Others complained that its services went on for too long, sometimes “excruciatingly” so, keeping them away—or squirming in their seats. Hotel guests, for their part, had no reason to leave the premises; they could just as easily avail themselves of an on-site prayer service.

“Excuses, excuses,” responded the summer synagogue’s stalwarts, noting that those who complained that it was too much of a trek down a country road thought nothing of climbing the side of a mountain later in the day. As for the hotel minyan? Housed in a makeshift, improvised space that only hours before had been used for “hops and card games and ragtime playing,” it was no sanctuary. Besides, services were so “hastily and perfunctorily” performed, they barely qualified as an exchange with the Almighty.

“Stand by your summer shul,” Catskill vacationers were entreated—to no avail. They had something else in mind, their attitude toward prayer of a piece with the ways in which Catskill hotel culture accommodated traditional ritual practice. Yes, most area hotels that catered to Jewish guests made sure that kashrut was observed. But since its imprint was invisible, subtle rather than overt, it didn’t ask much of them. Public displays of religiosity, on the other hand, were something else. Calling too much attention to themselves, they interfered with leisure’s gentle rhythms and, consequently, were often sidelined.

When, in the summer of 1917, Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, then well on his way to becoming a household name for his bold, energizing ideas about modern Jewish identity, stayed at a hotel in Tannersville—probably the Fairmont—for the weekend, he was dismayed, even affronted, by the prevailing Friday night atmosphere. There wasn’t one: no tangible signs such as flickering Shabbos candles, no sounds of guests making kiddush.

The absence of Sabbath spirit in an avowedly Jewish hotel in the Catskills so troubled Kaplan that he recorded the incident in his diary, calling it a “godless spectacle.” But the mise-en-scène didn’t trouble his fellow guests, not in the least. What they experienced was entirely to their liking: a Shabbos after their own hearts, with good food, a convivial atmosphere, spirited conversation within the company of their own—and then, on to the dance floor to shimmy the night away or to the parlor to play several hands of pinochle.

A Catskills vacation may not have lasted long, but its effects lingered well after the bathing suits and tennis rackets had been packed away. Like the latest dance crazes, it shook things up, giving rise to and licensing a new, self-consciously modern and compelling form of identity, one in which Jewishness pivoted more on affinity than on faith. Mount Sinai had furnished the Jews with one form of expression; the Catskill Mountains gave them another.

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies & Professor of History at the George Washington University, is currently at work on a biography of Mordecai M. Kaplan.