“AN HONEST JEW”

FLAMESKI—There is only one thing our race hates more than pork.

FRIEND—What is it?

FLAMESKI—Asbestos!

—Puck, December 5, 1900

Nearly 125 years later, the arguably witty joke about the “Honest Jew” in the satirical magazine Puck might seem antisemitic—which it was. And, yet, there was no denying the truth of the situation: In the decades after 1870, Jews on the Lower East Side and elsewhere in New York City often committed arson, deliberately setting their shops and tenement houses on fire, in a brazen attempt to obtain big payouts from insurance companies. According to historian Jenna Weissman Joselit, for example, “of the 128 arson cases reported by The New York Times between 1875 and 1899, Jews figured in more than one-quarter of them; in the 1890s alone, Jews were implicated in a whopping 44% of all arson cases described by the newspaper.”

Callous and seemingly without concern for the enormous danger and hardship their criminal actions caused—including the death of a child in one case—the “incendiaries” and “firebugs,” as they were referred to in the press, convinced themselves that burning down their properties was a normal part of doing business. Many of them got away with it and reaped the financial benefits; others did not and were incarcerated for lengthy prison terms.

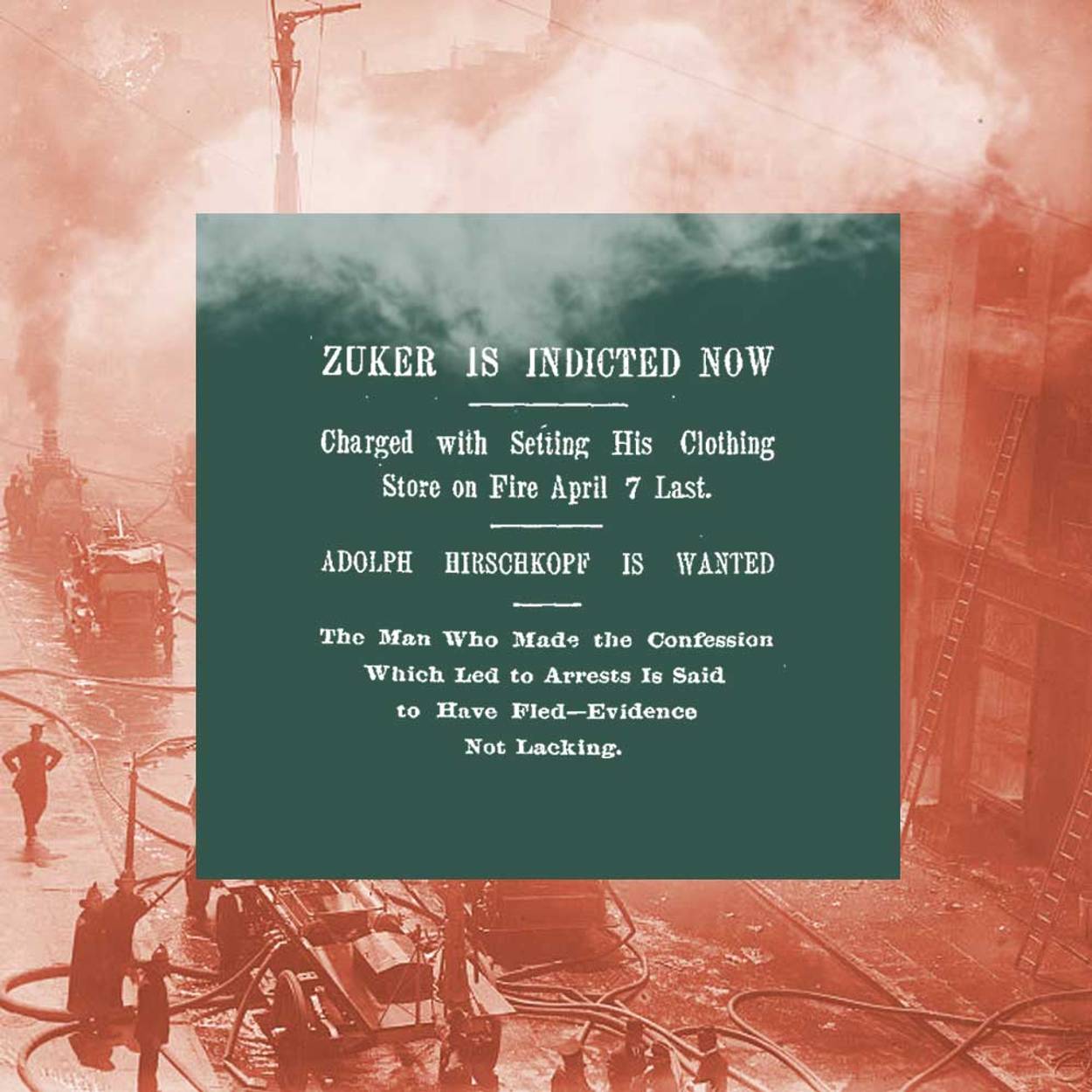

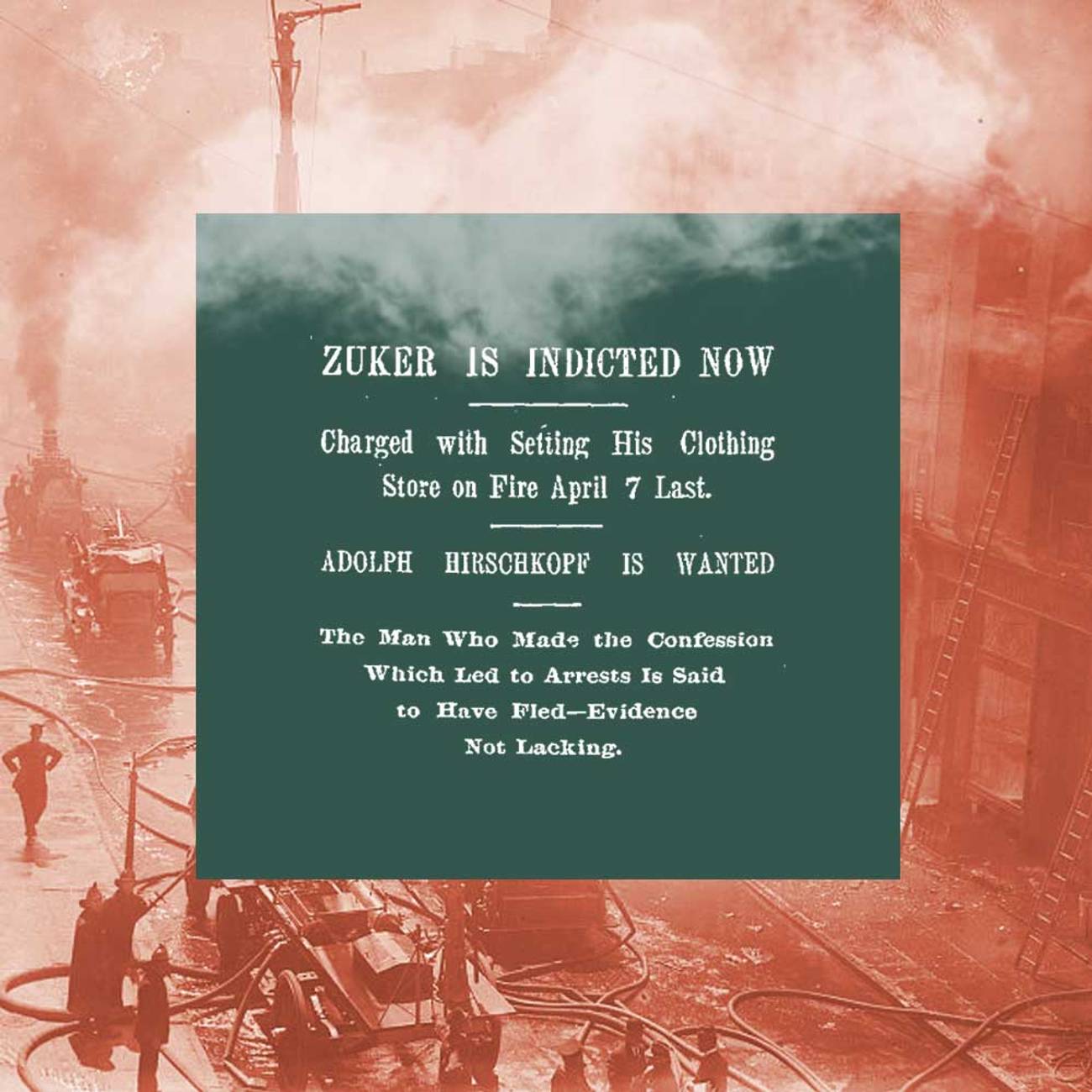

In late May 1895, Vernon Davis, an assistant district attorney, and Fire Marshal James Mitchell aimed to bring down what Davis called a “firebug brotherhood,” a loose association of Jewish property owners and insurance adjusters who were allegedly responsible for at least a dozen fires during the previous five or six years. Isaac Zuker was said to be the group’s leader, though it is not clear if that was indeed the case. He was connected to several of the men who were arrested and charged. Davis later estimated that the six to eight men who were indicted had defrauded insurance companies of at least $500,000 (nearly $18 million today). Zuker’s share of that money was difficult to determine.

In 1895, Zuker was about 48 years old. He and his wife, Rachel, had immigrated from Posen (Poznań), Poland (the city was then under the control of Prussia), to the U.S. around 1869. They had lived at various locations on the East Side, including in tenements on Allen and Orchard streets. Zuker worked hard as a tailor and merchant and succeeded. For a decade or so, he had operated a stall in Washington Market on the Lower West Side of Manhattan where he sold cutlery, crockery, and hardware. He later made and sold shoes in Philadelphia, where he and his family resided briefly. Then, having moved back to New York, he worked as tailor and operated small stores on the Lower East Side, on East Broadway, and in Brooklyn. He eventually owned several tenements, including one on Division Street on the East Side, where he also had a shop—which was to be the focus of his trial. Since 1892, he and Rachel and their four children lived in an upscale home in Union Hill, New Jersey. That he resorted to arson—more than once—to pad his already hefty bank account testifies to his greed and lack of scruples, to say the least.

The first individual Davis arrested was Morris Schoenholz, a 45-year-old cartman, an immigrant from Poland who lived with his wife, Anna, and their four children on the East Side. For a fee ranging from about $20 to $40 (approximately $700 to $1,400 today), Schoenholz started fires as he was instructed. Mitchell called him “one of the worst firebugs in the country.” That may have been an exaggeration, but Schoenholz later admitted to having started at least six fires going back to 1889, when he burned down a tenement on Grand Street. In 1893, he had received an 11-month sentence, which he served at Kings County Penitentiary in Brooklyn, for conspiracy to commit arson.

In 1895, Schoenholz was initially accused by Davis of being involved in an arson conspiracy with three other Jewish men, Harris Deitsch, Simon Rosenbloom (or Rosenbaum), and Morris Weiner, to burn the apartment house where they all lived at 285 East 4th Street. A few days later, Zuker and Abraham Krone, a clothing merchant, were also arrested on arson charges; Schoenholz was implicated in their crimes as well. Schoenholz and Krone were charged with setting a fire to Krone’s shop in early February 1893. And Zuker and Schoenholz were believed to have started several fires, including one on April 7, 1895, in Zuker’s dry-goods store on 10th Avenue at West 41st Street, and another, in early January 1892, in Zuker’s rundown tenement at 264 Division Street.

Five months later, Schoenholz, described by ADA Davis as “a fiend incarnate” and a “human pest,” was put on trial for his involvement in the fire on the apartment on East 4th Street. During the eight-day court proceedings, various witnesses—mainly two Jewish informants involved in fires with Schoenholz—linked him to the East 4th Street fire as well as several others. He was said not to have concerned himself with the tragic consequences and possible loss of life for adults and children in any of the fires that he started. For him, it was purely a way to make money. Midway through the trial, an allegation—which was later not proven—was made that Zuker and his associates in the “arson syndicate” were attempting to bribe members of the jury.

Despite Schoenholz’s lawyer castigating the informants as cowards and liars, it took only an hour for the jury to find Schoenholz guilty of arson in the first degree. Days later, the judge meted out harsh punishment, sentencing Schoenholz to 48 years of hard labor. As the reporters covering the trial observed, Schoenholz “broke down” and was “shrieking and moaning” as he was dragged out of the courtroom. Editors of The New York Times wrote that a “more detestable scoundrel never existed.”

One of the witnesses who testified against Schoenholz was Adolph Hirschkopf, a former insurance adjuster, who lived on Henry Street on the East Side. He believed that cooperating with the District Attorney’s Office would save him. But he was mistaken. In mid-November, Hirschkopf and a partner, Meyer Dietscheck, were arraigned on a charge of murder for causing the death of a 4-year-old orphaned girl, Lizzie Yaeger, by starting a fire on May 23, 1894, at a tenement on Suffolk Street near Rivington Street. The fire began with an explosion at a saloon on the ground floor of the building that fire officials later determined was set off by a mixture of benzine, naphtha, and gasoline. There were 60 people in the building at the time of the explosion. In the confusion, no one helped Lizzie escape and she burned to death. Hirschkopf, who was identified as the main culprit of this tragedy, denied having anything to do with it. Yet he, too, was found guilty and sentenced to 48 years in prison.

It took until mid-October 1896 before Zuker was put on trial for arson in the first degree. Zuker did not light the match that triggered the fire at his tenement on Division Street—he hired Schoenholz to do that—but he planned the entire operation together with his chief accomplice, Max Blum, who lived in an apartment right next to his shop. The two shared a wall. At least, that was what the two main witnesses, Schoenholz and Gustave Myers, who was at one time employed by Zuker, stated at the trial. The trustworthiness of both men was suspect, a fact later pointed out by the judge in his charge to the jury. Schoenholz was serving a life sentence for arson and Myers later admitted in court that he recently had set fire to an East Side house. At the same time, they had intimate knowledge of Zuker’s actions that ADA Davis felt still strengthened his case.

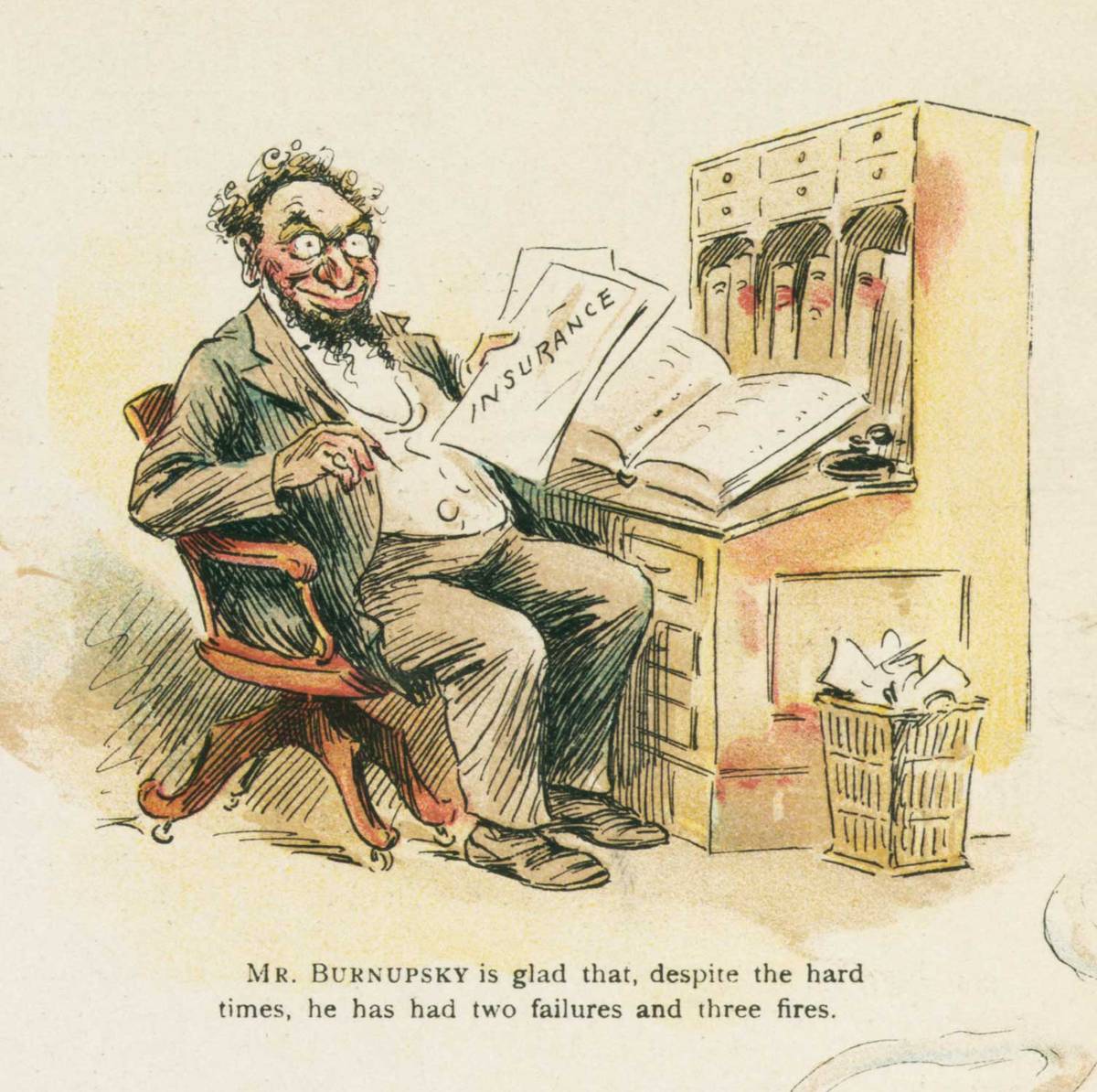

A cartoon featured in an 1894 issue of ‘Puck’ Library of Congress

Zuker was likely caught off-guard by Schoenholz’s testimony. Having been locked up in Sing Sing for nearly a year by this point, Schoenholz decided to bare his soul. Davis did not seek Schoenholz’s assistance in Zuker’s prosecution, nor was he coerced or offered a deal; Schoenholz offered to relate what transpired with Zuker on his own accord, though according to a Brooklyn Daily Eagle report he likely believed that his cooperation would result in a reduction of his sentence or even his freedom.

Schoenholz and Blum had lived in the same town in Poland and had known each other for many years. Blum had introduced him to Zuker in 1889 or 1890 and Zuker had hired Schoenholz to transport clothing and supplies with his horse and wagon. According to Schoenholz, it was when the three men were together at Blum’s apartment in early August 1891 that Zuker had first mentioned that he planned to burn his Division Street store. He was concerned that the Board of Health was going to condemn the building and force him to undertake costly repairs. “I got to burn down this shanty,” Zuker had told Schoenholz. Myers testified he had a conversation with Zuker in July 1891, a few weeks before Schoenholz and Zuker met, and Zuker had used the exact same words: “I am going to burn the shanty down.”

Zuker had been unable to purchase insurance on the property because he was considered a bad risk, but he had hired a manager by the name of Seltzer who was able to buy a $5,000 policy in his name. And his neighbor Blum had $1,000 of insurance on his belongings and apartment. In the following months, a scheme was hatched to set a fire that would destroy Zuker’s clothing shop and Blum’s apartment. The two planned to share any insurance money they later acquired.

‘I am going to burn the shanty down.’

Zuker wanted to wait until after the Jewish holidays were over before the deed was done. In preparation, Schoenholz moved boxes of clothes to other buildings owned by Zuker in New York as well to a new store he had opened in Newark, New Jersey. In late December and early January, the scene was set for the fire. Remnant clothing that remained in Zuker’s shop was strewn all over the floor. A hole was made in the wall between the shop and Blum’s apartment and a curtain soaked in benzine was pushed through it. A few empty butter tubs containing a total of about 20 gallons of benzine were placed around the shop with pieces of cloth dipped inside of it and benzine was also poured on the material on the floor. Finally, Zuker put a candle inside a piece of soap and attached a long string around it. As he did not want to be too close to the building when the fire started, he paid Schoenholz $25 to light the candle and pull the string so that the cloth would burn quickly and easily. He was promised more money if Blum collected the insurance. Schoenfeld said he asked Zuker why so much benzine had to be used and Zuker replied: “I want the shanty to burn right to the ground so it will be at least 60% damage[d], then the insurance company has to pay the full amount or will build it anew.”

There was concern about a cigarmaker who lived next to Blum, but Blum’s sons were tasked with ensuring no harm came to him—though little worry was expressed about the danger posed to the families, many with young children, who resided in other nearby tenements. At about 9 p.m. on Jan. 4, 1892, an evening with sufficient wind, Schoenholz lit the candle, pulled the string to topple it, and the shop and Blum’s apartment immediately erupted in a blazing inferno. Police officers who were close by summoned the fire department and Schoenholz watched from a distance until the fire was put out. No one was hurt. According to Myers, he later saw Zuker on Grand Street, about three blocks away, and Zuker, seeing the billowing smoke, was worried the fire had not been strong enough. But it was. His store, Blum’s apartment, and other parts of the tenement were reduced to rubble. Their plan had initially worked: Zuker was paid $3,000 by the insurance company and presumably Blum collected on his $1,000 policy.

A subsequent investigation of the blaze by fire officials confirmed that benzine and kerosene had been used as an incendiary to ignite it. (It is unknown whether the insurance companies attempted to recoup their payouts.) Zuker was defended by William Howe of the noted law firm Howe & Hummel along with his associate Abraham Levy (who had acted as Schoenholz’s attorney during his trial in October 1895), who tried to show that Zuker “was a man of good character.” Zuker testified on his own behalf and naturally denied everything that Schoenholz and Myers had said. He insisted that he did not know Schoenholz and that Myers was merely a disgruntled former employee, angry that he had lost his job. They both had lied, Zuker claimed. On cross-examination, however, Zuker could not adequately explain why he had given money to Schoenholz’s wife, Anna, a year earlier while Schoenholz was on trial.

The members of the jury saw through Zuker’s deceptions. He was found guilty of arson in the first degree and sentenced to 36 years in prison. His wife and children reacted to the verdict with tears and cursing. His lawyers appealed the verdict on the grounds that the key testimony by Schoenholz, an accomplice in the crime, could not be fully corroborated. The appeal failed: In August 1897, the New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division, upheld the verdict.

According to the records of the 1915 New York state census, Zuker was still in Sing Sing at the age of 68.

Those like Zuker, Blum, and Schoenholz, among many other Jews, who were convicted of committing arson brought derision on the entire East Side Jewish community—and, in truth, on Jews throughout New York and beyond. As The New York Times declared at the conclusion of Schoenholz’s trial, “it is necessary that examples should be made which shall become familiar to the entire East Side, or so much of it as is inhabited by the latest and least desirable element of our immigration.” Or, put more bluntly two years later by lawyer Frank Moss in his history of New York City, The American Metropolis: “The firebugs form a definite feature of life on the East Side. Many of the miserable Poles and Russians [Jews] make a business of effecting insurance and then setting fire to their stores and homes, and defrauding the insurance companies, regardless of danger to human life.”

Nearly two decades earlier at yet another series of arson trials, four young Jews—“Four Heartless Rogues” as the Times depicted them: two peddlers, a cigarmaker, and a tailor—all received life sentences of hard labor for starting a fire in the tenement rooms of one of them. Their particular ploy was to insure their property and belongings for more than it was worth (clearly the insurance companies were not paying attention), start a fire, and collect what they claimed was owed to them. Fire officials figured out their scheme, watched them, and eventually caught them in the act.

At the joint trial of two of them, their defense attorney suggested that there was “prejudice against the prisoners for being Jews.” In his charge to the jury, the presiding judge addressed this issue. “Of course, there ought to be … no prejudice against them or in their favor because of their race or religion … For my part I can say from the very bottom of my heart that I have no prejudice against the prisoners nor any prejudice against any of their race.” He urged the jury members, a few of whom were Jewish, “to approach the question whether these men—not as Jews or Gentiles, but as human beings—on the accusation before you, are or are not guilty.”

For an era in which antisemitism was part of daily life on the East Side and elsewhere, the judge’s instructions and sentiments were wise though idealistic and likely not adhered to as he wished. For decades to come, arson and Jews were linked together—and not unjustifiably—as Puck magazine and other newspapers and journals continually reminded their readers.