Reconsidering Camp

As a kid, I focused on the things I didn’t like during those summers away from home. As an adult, I realized how much I learned about myself there.

I didn’t ask to go to Habonim-Dror Camp Galil in the summers of 1987 and 1988, when I was 12 and 13 years old. In fact, I felt like I was being exiled from my family for seven weeks. When I asked my parents why, my father said dryly, “We don’t know what else to do with you.”

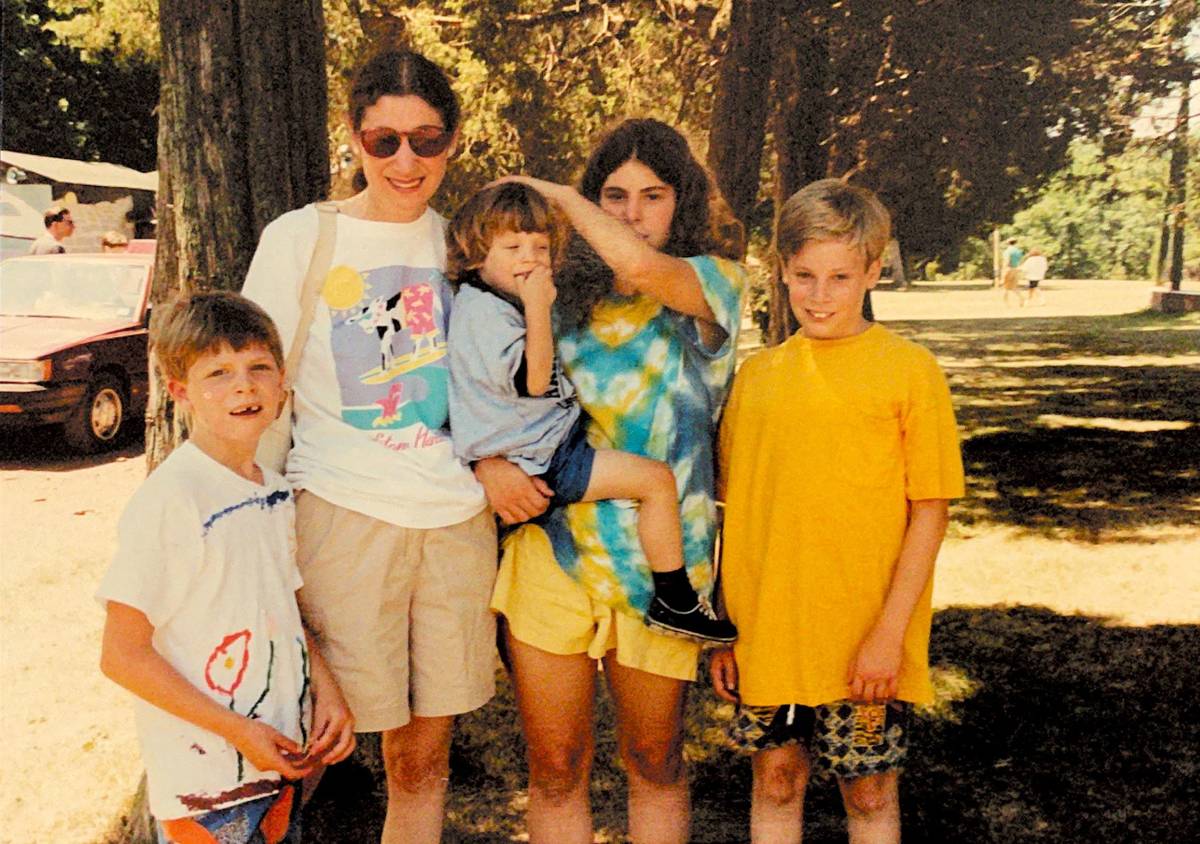

True, my parents had my three younger brothers to attend to, one of them not quite 2, and they were also taking care of my 24-year-old aunt, who was having some emotional issues. But I was having my own crisis: At 12 I was in that unnerving in-between place—surprised to suddenly find myself too old to enjoy playgrounds and carousels, but too young to understand who I was or what my interests were. I was smart, but I didn’t quite know it, and because I was constantly and unmercifully bullied at school, I was prickly and guarded.

After I grew up, I never really wanted to look back at Galil, because what I remember most was my discomfort there—my unease with myself. There were the mortifying new curves, the too-curly hair, the too-thick eyebrows, the Clearasil and the Kotex. There were the smaller, cuter girls who whispered to each other while glancing at me, or pointedly said, “there’s a reason you have trouble making friends!” There was the time a boy groped me in the pool. There were the arguments, the refusal to follow directions, and the time I lay face down in the grass after everyone else had trooped off to lunch.

It took me half a lifetime and having my own kids to realize that my experience at Galil was so much broader than these embarrassments, which were really just a factor of being 12 and 13. In retrospect, and in spite of them, what I learned at Galil became a thread that ran through all the years that followed.

Located in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, outside of Philadelphia, Camp Galil was sweaty and dusty. The dust would stick to the sweat on my arms and legs, and in the evening, clouds of gnats would linger near my sweaty face. At night, I left a vaguely girl-shaped dirt stain on my bed sheets. Twice I had to be taken to the doctor in town, once because I got poison ivy so severe I needed steroids, and another time because I had oozing impetigo that required antibiotics.

We spoke camp Hebrew at Galil, but I’d never quite taken to Hebrew at Hebrew school, so I stubbornly insisted on calling the tzrifim “cabins,” the madrichim “counselors,” the kikar “the field,” and I ate in the dining hall, which everyone else called the chadar ochel. I shied away from making announcements, which had to be in Hebrew, even after I learned some words I could string together. The language just felt too alien in my mouth.

Habonim-Dror is part of the Labor Zionist movement, so Galil was run like a kibbutz, which meant everyone did work detail, avodah, in the mornings. Some kids cheerfully signed up for briyut and ashpah and went off to clean the toilets and handle garbage, but I tried to choose things like salad-making or tree-bench building. We had kupa, which meant that everything belonged to everyone and should be shared, but I didn’t like lending my shampoo or my T-shirt. And I absolutely refused to shower in the communal shower house without a bathing suit.

On Friday afternoons, we had to carry our bunk beds out of the tzrifim so they could be cleaned in preparation for Shabbat; the chadar ochel also had to be mopped, to prepare for rikud, the joyful Israeli dancing after dinner. I have a distinct memory of sitting on my bed and refusing to carry it outside, even after several madrichim asked me nicely. And I remember trying to sit out rikud, too—no one was going to force me to dance!

In short, I was kind of a pain in the neck, and probably not the ideal Habonim-nik, but it grew on me. Ultimately, I loved Galil: the square-pizza picnics on Friday afternoons, and the long, slow L’cha Dodi on the kikar, as evening fell, freshly showered and holding hands. I loved being pulled up from the sidelines and into the exuberant Israeli dancing. But it was still complicated.

I was kind of a loner: No one quite got me, and I wasn’t always tactful. When pink eye spread through the bunk, I remember snarling, “Only dumb, uneducated people call it pink eye! It’s conjunctivitis!” But they still accepted me—I was part of the community. No one bullied me at Galil. I cherish the memory of a popular male K.M. Bet (counselor-in-training) greeting me at the tree-bench we were building with a big grin and a singsong, “You do what you wanna do! That’s why we love you, Roseanne!”

There was music everywhere: Before lunch every day we had shira, and holding up big poster boards with the lyrics, the madrichim taught us to sing everything from camp songs to “Erev Shel Shoshanim,” to Run DMC’s “You Be Illin’.” Music blasted all day long from the ram kol—Simon and Garfunkel, Joni Mitchell, the Beatles, the Hair cast album. We sang in the chadar ochel before and after we ate. My madricha, who always wore a Barnard T-shirt and made sure we could pronounce it, played Suzanne Vega and Tracy Chapman at rest time.

It was at Galil that I discovered that I loved to act. We had afternoon chugim, interest groups, and I chose chug drama, and we sat around doing scenes and monologues. I got so into it that they gave me the lead in one of the weekly Shabbat plays—a takeoff of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, except that he escapes from camp. I played the Cameron character. Everyone congratulated me afterward and told me what a wonderful actress I was.

At the end of the summer, I was paid the ultimate Galil compliment: I was shmeryled. A shmeryl is a publicly read rhyming poem describing a camper or a counselor, with the person’s name revealed at the end. Once I was shmeryled, I got to choose the next person to honor, and write a poem of my own.

In ninth grade, after my second summer at Galil, I tried out for my high school musical, and that was it—I wanted to do theater. I begged my parents to send me to Stagedoor Manor in 1989 and 1990, the summers I was 14 and 15. Stagedoor wasn’t a Jewish camp, but in some ways it might as well have been. We were housed in the ramshackle remains of the Karmel Hotel in the Catskills, and we put on 12 fully realized plays and musicals every three weeks. Occasionally we put on our black-and-white cabaret outfits and toured what was left of the borscht belt, singing snippets of whatever we were rehearsing to the elderly Jewish audience. When my parents drove up from the Philly suburbs to see me perform, they always took me out to eat at Kaplan’s, the famous kosher deli in Monticello.

I sang and danced and ran my lines in the corridors between rehearsals. I invented inner lives for my characters and wrote their stories in my notebook. The rehearsal studios had panoramic views of a gigantic indoor pool, but I never saw it used—everyone was too busy to swim. For some reason, I subsisted mostly on garlic bread and pistachio ice cream, but I was perfectly happy with that.

Stagedoor kids were misfits and theater nerds, many of them already professionals, a good number of them gay. At Stagedoor I was driven and perfectionistic, eager to please. My oddities seemed not nearly so odd when we were all in service to the same thing: creating theater. We tried to be fair and inclusive to everyone—the goal was to be a cohesive cast with a good rapport, and winning “best ensemble” at the closing banquet was one of the highest honors.

Stagedoor was paradise. If I had any complaint about it, it was only that I wished I was getting bigger roles. Still, I played some good ones, and I remember those summers with happiness and a sense of pride.

Even though it was undeniable that parts of Galil were wonderful, for years I saw my time there as something that had been “corrected” by Stagedoor. But I don’t see it that way anymore.

This year, for the first time, I am sending my two older kids, 16 and 12, to overnight camp. I never before pushed them to go—they were always happy at day camp, and it was too expensive anyway. But the pandemic changed everything. My kids have now spent the better part of 15 months holed up in their bedrooms, staring at screens. I want them to emerge from their dormancy, stretch their limbs, and remember how to be kids.

I never thought I’d do it, but I chose Camp Galil for my daughter Liora, who is 12. Because Galil, I realized, was the testing ground for who I became. It was where the shift happened, from child to adolescent, so subtle that it is only evident when I look back. Certainly I discovered my love of theater and music there. It was there that I first experienced the uniqueness of Shabbat, the stillness and the joy. Galil was why I went to Barnard. And the Hebrew that I initially refused to speak became the foundation for my recent near-fluency as I navigate cantorial school. But most importantly, even if I didn’t always want to participate, I internalized the messages about community, how to include others, and how to speak kindly. After all, what is “best ensemble” if not a version of kupa?

For Liora, at Galil, I wish face-to-face conversations with her bunkmates, poison-ivy-free tiyulim (hikes), magical Shabbats, barefoot dance sessions, and the freedom to lie in the grass of the kikar, swat the gnats, and find hints about who she will become. May she find her community there. And if she isn’t always cooperative, that’s OK—I know Galil can take it. I can’t think of a better thing to do for her.

Roseanne Benjamin is a freelance writer in Manhattan.