Samaritans on the American Protestant Mind

In the early 20th century, interest in the ancient community—and its religious artifacts—caught the attention of everyone from tourists to researchers to Mark Twain

The war made a sad break in our work for the Samaritans, and the death of Mr. Warren is for us a more serious matter. He was greatly interested in this work and his financial contributions far exceed all other sources of supply. I don’t know if there is anything we can do for the Samaritans just now. During the first two years of the war we sent them help through Mr. [John] Whiting [the former American deputy-consul in Jerusalem]. Unfortunately they quarreled with him. His report seems to indicate that their current need is self-reliance; a dependence upon their own exertions for support and an agreement among themselves as to their policy for the future. ...

Concerning the religion of the Samaritans, we have had this feeling. That we had no present call to force the hand of Providence. This little nation has been kept in existence for a very long time and it would be better for them to see in us a Christian spirit than that we should organize a campaign to proselyte them.

I am glad that they asked for your Arabic hymn book. It would be interesting to know that they are singing Christian hymns.

—Letter from Rev. William Eleazer Barton to Mr. Mortimore, June 14, 1920

In September of 1902, the Reverend William Eleazer Barton returned from a well-publicized steamship tour of Europe, North Africa, Egypt, and the Holy Land. Pastor of a large and prominent Congregationalist community in the Oak Park suburb of Chicago, Barton was an author of popular church literature and future spiritual biographer of Lincoln. The cruise itinerary was, according to Barton, patterned on the journey undertaken by Mark Twain and described in Twain’s 1867 The Innocents Abroad. Upon his return, Barton announced that he would soon publish a travel memoir of his own. The 1902 book, titled The Old World in the New Century, reads as a more religiously concerned version of Twain’s. Barton takes a similar skeptical approach to the enterprise of tourism and to the peoples of the old world, and evinces a similarly wistful (if less humorous) perspective regarding the decline of the ancient civilizations. Chicago newspapers mentioned Barton’s forthcoming book in passing. They spoke at length, however, about a mysterious and exciting artifact that Barton had brought back from his travels: a Samaritan Pentateuch of purportedly ancient origins. Two years later, Barton published an English translation of the Samaritan Pentateuch based on his manuscript. Once again, Barton’s book received passing mention in local newspapers, which, however, delighted in discussing Barton’s Pentateuch manuscript.

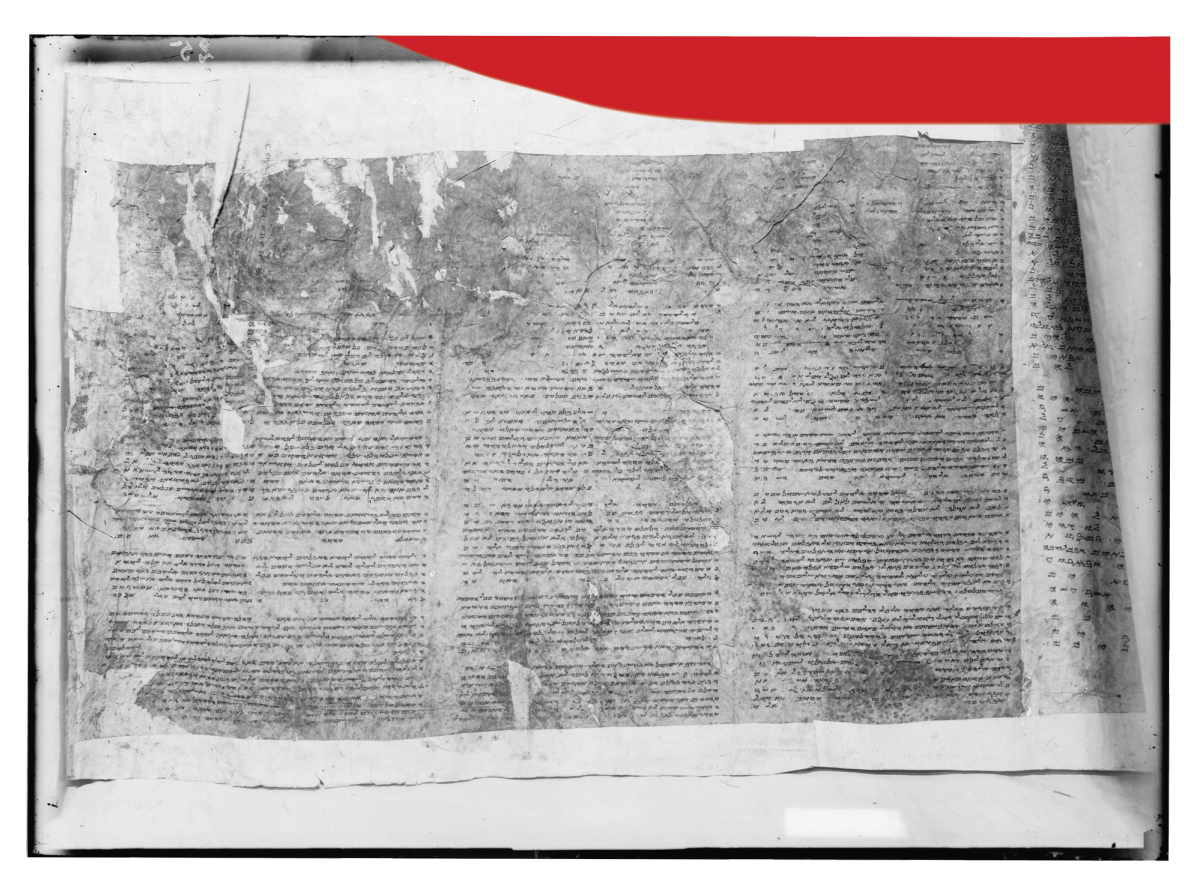

The story Barton told, which was often somewhat embellished in newspapers, was as follows: On his visit to the Holy Land, he had sought out the Samaritans of Nablus and made the acquaintance with a leading priest, perhaps the high priest Jacob son of Aaron. Impressed by Barton’s letter of introduction, the priest gave Barton the rare honor of a chance to see the Abisha scroll, ascribed to Abisha the grandson of Aaron the high priest. The scroll is believed by Samaritans to be the most ancient copy of their Torah in the world and it has historically been inaccessible to foreigners.

Outside the synagogue, Barton bought several small manuscripts produced by members of the community for sale to tourists. A young priest, noting Barton’s interest, beckoned the minister away from the synagogue and into the adjoining courtyard of the high priest’s home. There they ascended a staircase to an upper room. The women of the priest’s household realized what was about to transpire and, following the men, “made vehement protestations against what they judged he was about to do.” The priest succeeded in barring them from the room and bolted the door behind himself and Barton. From beneath the bed, the priest produced a large copy of the Samaritan Pentateuch in scroll form. The two men haggled for hours, the language barrier between them making negotiations very difficult. In the end, Barton secured a copy of the Samaritan book of Genesis in a handsome tin case, a less precious replica of the sturdier brass case in which the older scroll was encased. The priest hid the case inside his flowing robes so as not to arouse the suspicion of his co-religionists and escorted Barton out of the compound as twilight descended on the city. Later newspaper accounts would claim that Barton himself had secreted the manuscript out of the city beneath his coat.

To Barton’s great joy, the next morning another young priest he’d seen in the compound the day before approached the Americans’ camp. He produced from beneath his robes the same scroll Barton had seen the day before. Barton would later claim this scroll to have been a copy of the Abisha scroll itself. Barton and the priest reached an agreement on a price and Barton secreted his precious acquisition to Jerusalem, from whence he immediately sent it back to America.

Both upon his return, and, even more so, after he’d published his translation, newspapers fixated on Barton’s account of purchasing the Pentateuch. Many of them repeated the mistaken idea that Barton’s copy was one of only twenty Samaritan Bibles in the world, although it was indeed a rare example of a Samaritan Torah scroll. Others proclaimed the Samaritan tenth commandment, which states that worship shall be eternally centered on Mount Gerizim, to be a new discovery made via Barton’s manuscript. The Chicago Tribune proclaimed in a headline “Chicagoan finds new Bible verse.” Several other newspapers similarly depicted the Samaritan Pentateuch as uncharted territory being explored by Barton, reframing Barton’s story as a quest to discover the true location where God had commanded Moses to erect His altar. Another headline declared that Barton’s discovery “ends a biblical dispute” and proved that the temple was meant to be built on Mt. Gerizim, as the Samaritan woman at the well had told Jesus.

Barton’s visit to the Samaritans was, like his itinerary more generally, probably inspired by Twain’s visit thirty-three years earlier. In fact, when Barton brought his manuscript home to Chicago, he tried to ascertain whether there were any other such manuscripts in the United States and corresponded with Twain. He wrote about their correspondence in his memoir:

After my return from Palestine, I chanced to notice in Innocents Abroad a sentence which stated that Mark Twain when there had procured from the high priest of this ancient Samaritan community, “at great expense, a sacred document of great antiquity and extraordinary interest,” which, said Mark Twain, “I propose to publish as soon as I have finished translating it.” Wondering if Mr. Clemens [Twain’s birth name] had any experience similar to my own, I wrote to him, asking him whether he also had a Samaritan Pentateuch, and have received his reply, stating that he had not seen a copy of Innocents Abroad for many years, and that all recollection of buying the manuscript referred to has entirely passed from his mind. I presume that what he bought was some of the smaller souvenirs, as he could hardly have forgotten a purchase like mine.

Twain’s account was influential in establishing the Samaritans as a staple stop along the American tourist route of the Holy Land. It also likely set the precedent for tourists visiting Nablus to purchase a Samaritan manuscript or a fragment of one.

The stories told by Barton and Twain are examples of a genre of Samaritan tales popularized by mostly Protestant missionaries, researchers, and would-be explorers during the early twentieth century. Paralleling well-worn orientalist tropes, these stories always involved western, usually Protestant, men who make the perilous adventure to Nablus, where the leaders of the long-suffering Samaritan people entrust them with the purchase of sacred and rare manuscripts. The Samaritans in these stories bear motives that are often depicted as a mixture of financial desperation and/or greed and, in some cases, the desire that these westerners will spread knowledge about Samaritan culture and belief. Some but not all of these authors evince the hope expressed by Barton’s correspondent Mr. Mortimore in the letter transcribed at the beginning of this article: to convert what they saw as the unchanged-since-ancient-times Samaritan community to Christianity. And even Barton himself implied to Mortimore that “the hand of providence” would eventually see to that result. The significance of the purchased manuscripts is often overstated in stories of this type. As Barton found out through correspondence in 1903, the New York Public Library owned two Samaritan Bible codices. The genre of which Twain and Barton’s accounts of Samaritan life are an example reflects antiquarian more than academic concerns.

Since the Renaissance, scholars have taken interest in the Samaritans in sporadic waves. Until the late nineteenth century, these scholars were primarily interested in the Samaritan Pentateuch. By that time, scholars came to a consensus that the Samaritan Pentateuch dated to later than the Masoretic text. To nineteenth century scholars searching to recreate the original biblical text, this rendered the Samaritan Pentateuch of little value.

Shortly after the interest of textual scholars in the Samaritans had waned, however, the Samaritans became a focus of popular anthropological and religious interest. As steamships began to afford the middle class the means of traveling the world, the Samaritans became a staple stop on the tourist route for young bourgeois men and Christian pilgrims touring through Ottoman Palestine. In his travel book, Barton notes that the low cost and extravagant accommodations aboard his own cruise would have been impossible a generation earlier when Twain had taken the first cruise through the old world.

Tourist interest in the Samaritans was such that it spawned a new genre of Samaritan artifacts by the early twentieth century, namely Samaritan manuscripts and artifacts produced explicitly for sale to visitors. In addition to the large tin Torah case, Barton brought home a miniature scroll contained in a small case that is an example of such an item. The miniature Samaritan scroll in the Congregation Emanuel collection in New York City is an almost identical example of this genre of tourist scrolls. Many manuscripts in codex form were also produced for the tourist trade, often containing one or another biblical book instead of the full Bible codices used within the Samaritan community. Drawings of the layout of the Tabernacle and were also widely sold to visitors to the Samaritans in Nablus. This touristic interest meant that Samaritan manuscripts became a popular gift for libraries across America, and some of these were very significant. In a letter between the two men, the Samaritan high priest Jacob son of Aaron requested that Barton put him in touch with anyone who might want to purchase a Samaritan manuscript, as long as Barton would serve as intermediary.

… Therefore I dared to … ask you if any should ask about books of our law of our prayers I should be only willing to send them on to you. … I am willing to copy any of our books to any one that wishes to buy them, whether in Arabic or Hebrew.

(Jacob son of Aaron to Barton, September 26, 1904)

Barton thus became a go-between for American individuals and institutions who wished to visit the Samaritans or purchase manuscripts from them. He also frequently lectured about the Samaritans and the Samaritan Pentateuch at venues such as the Chicago Society of Biblical Research.

To such tourists, Samaritans were of interest as a link to the religion of ancient Israel. They also became, during a period in which social Darwinist racial science was gaining popularity, important as racial specimens. An excellent example of the racial type of interest in the Samaritans is the article titled “Samaritans: Anthropology,” based on fieldwork by a young Harvard scholar named Henry M. Huxley that appeared in the highly influential The Jewish Encyclopedia in 1905. Huxley endeavors to locate the Samaritan race in relation to the Jews. He argues they bear similarities to Jews and were indeed the only “pure” example of the ancient Jewish race but that they were, however, a “degenerate” version of that type:

The pigmentation of the Samaritans, as indicated by the color of the hair and eyes, is shown in the following tables. ...

These tables make it clear that the Samaritans are by no means an exclusively brunette type. As seen by the presence of blue eyes and light hair or beards in a considerable percentage of the individuals examined, there is, on the contrary, a distinct blond type noticeable in the group.

The general type of physiognomy of the Samaritans is distinctly Jewish, the nose markedly so. Von Luschan derives the Jews from “the Hittites, the Aryan Amorites, and the Semitic nomads.” The Samaritans may be traced to the same origin. The Amorites were “men of great stature”; and to them Von Luschan traces the blonds of the modern Jews. With still greater certainty the tall stature and the presence of a blond type among the Samaritans may be referred to the same source.

The cephalic [head size] index, much lower than that of the modern Jews, may be accounted for by a former direct influence of the Semitic nomads, now represented by the Bedouins, whose cephalic index, according to measurements of 114 males, is 76.3. The Samaritans have thus preserved the ancient type in its purity; and they are to-day the sole, though degenerate, representatives of the ancient Hebrews.

This text betrays a distinct prejudice against both Jews and Samaritans, ascribing greater “purity” to the Samaritans but also designating them as “degenerate,” in addition to asserting Samaritan antiquity over Jewish claims. Surprising as that may seem this is not the only place where anti-Jewish racial prejudice found its way into The Jewish Encyclopedia. Other examples include a supposed Jewish proclivity against art and the supposed prevalence of color-blindness among Jewish males.

The Jewish Encyclopedia article shows interest in the Samaritans among the Jewish community that was also expressed in Jewish tourist literature. Isaac Mayer Wise’s American Israelite and other contemporary American-Jewish newspapers published excerpts of travel accounts that discuss the Samaritans every few years. In Zionist travelogues of Eretz Israel, which were often intended to inspire European and American-Jewish youth to immigrate to Palestine, the Samaritans were a common feature. David Ben-Gurion and Izhak Ben-Zvi’s 1918 Yiddish language touring guide, Erets Yisroel in Fergangenheyt un Gegenvart (The Land of Israel in the Past and the Present), approaches the Samaritans in a way that would later become a centerpiece of Ben-Zvi’s research on this group and activism on their behalf. In the course of their description of Shekhem, they describe the Samaritans as “… live in their own little quarter of the city, which is called Haarat A-Samara, along the path that leads to their holy precinct on Mt. Gerizim.” Ben-Gurion and Ben-Zvi (later Israel’s founding prime minister and second president, respectively) depict the Samaritans as both distinct from the Jewish people but also part of their story. In this vein, they devote several pages to the history of the Samaritans, emphasizing that they, like the Jews, had tenaciously fought to remain in their holy land, describing the Samaritan wars against the Byzantines in heroic terms. They conclude their account of these bloody wars by noting that, despite the persecutions enacted by the Byzantines after the revolts,

they were never completely exterminated, despite all of the attempts at doing so, and until today one finds the beloved and stubborn devotees of Mount Gerizim at the foot of their holy mountain in their old native city upholding the customs and the cult of more than two-and-a-half thousand years ago.

Like The Jewish Encyclopedia, the Protestant iteration of this wave of popular interest in the Samaritans often echoed antisemitic tropes. Protestant scholars who saw Samaritan practice as indicative of ancient Judaism prior to Pharisaic “deformation” of the biblical religion were following a well-traveled trail of depriving the Jews of their day of the honor bestowed by their ethnonym. Some members of the British Israelite movement, which claimed Israelite descent for the British, saw Samaritans as their kin but considered Jews imposters. Nineteenth century European antiquarians had suggested that the Samaritans were descendants of the true Jews while European Jews were simply Khazars, an almost mythical Central Asian people who, according to legend, converted to Judaism during the 8th-9th century. One newspaper proclaimed in its headline that Barton’s discovery “Affects Jewish Belief.”

Barton never endorsed the sensational claims made by newspapers. He did errantly believe, however, that a Samaritan chronicle text that he had brought back containing the narrative of Jesus’ life was an independent witness to the New Testament. It was this Christian angle that motivated Barton and the Michigan industrialist Edward Kirk Warren to found a committee dedicated to aiding the Samaritans of Nablus in 1913. Over the next decade and a half, Barton would advise Warren on the acquisition of several important Samaritan artifacts. Robert T. Anderson suggests that Warren retained hope throughout his life that more Samaritan documents might be uncovered that would further corroborate New Testament narratives.

“The American Samaritan Committee,” as Warren and Barton’s project was called, hoped to support Samaritan purchase of land for a new, protected neighborhood in Nablus, to purchase the Samaritan holy precinct on Mt. Gerizim, and to found a school where Samaritans could receive a modern education. Fundraising ads for the committee were placed in various Christian publications, often including photographs of Samaritan life. This project was part and parcel of Protestant missionary activity directed toward Jews and Arabs in the holy land, though the American Samaritan Committee was ambivalent about outright proselytization, as noted above. This ambivalence may have been the result of Barton and Warren’s fascination with the Samaritans as biblical relics to be preserved. Protestant missionaries sometimes expressed these attitudes toward Jews as well for similar reasons.

For his own part, Barton developed a relationship with Jacob son of Aaron, becoming the last westerner to conduct an extensive correspondence with the Samaritan community by post, a tradition stretching back to several renaissance polymaths. These letters contain discussion of Samaritan history and practice as well as of practical matters relating to Barton’s fundraising on behalf of the community and its internal affairs. After speaking at a World Sunday School Convention in Jerusalem at Barton’s behest, Jacob wrote to Barton regarding the Chamberlain Warren Torah scroll case, which Warren’s agent from the American Colony had apparently not yet fully paid for. He enclosed a copy of a manuscript he’d written about Samaritan history that is now in the Barton Collection at Boston University:

I had decided to send you a copy of our history, which is well translated in Hebrew. If you should have it printed in the Arabic and English languages, (I should like) that you send us a part of the edition … I searched for three years for material for this history …

(Jacob son of Aaron to Barton, September 26, 1904)

Barton went on to commission several original works from Jacob. Several of these remain unpublished but a few were, with an introduction by Barton, and can be found in libraries around the country.

In their attempts to raise money for the Samaritan community, Barton and Warren relied on the fact that the image of the Samaritans was by this time firmly engraved in the religious and visual culture of the west. The New Testament account of the Samaritan woman at the well was a key symbol of the new covenant (in which Christians would worship neither on Gerizim “nor in Jerusalem”). And the parable of the Good Samaritan was a staple of popular visual culture, a symbol of Christian charity. In liberal nineteenth century Protestant circles, the good Samaritan had a further significance as a symbol of ecumenism and tolerance, key nineteenth century liberal values. Hospitals, at the time generally charitable institutions, often took the name of the Good Samaritan for this reason.

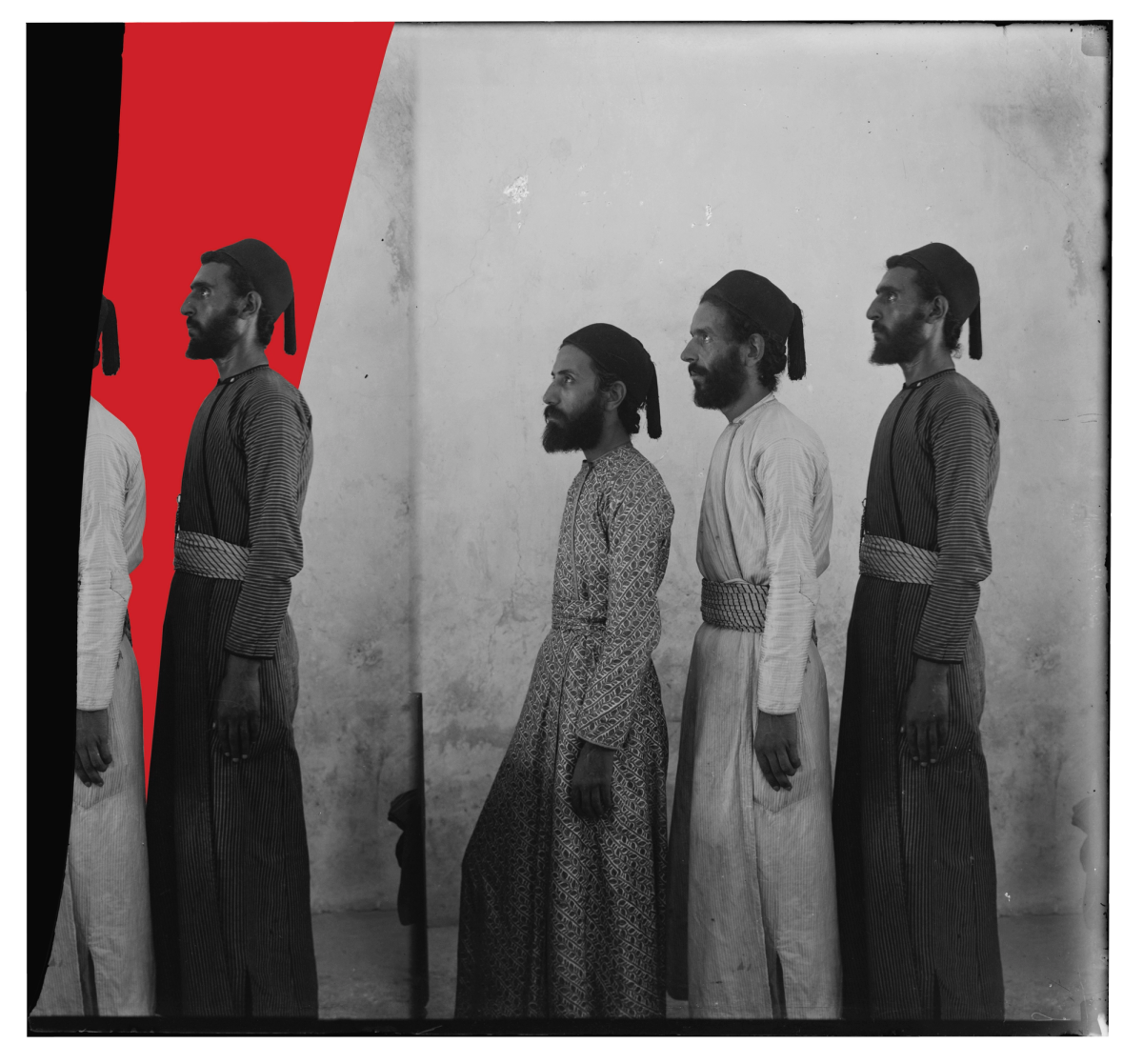

With the popularization of travel and photography, Samaritans also became a part of the visual culture of the tourism industry. Like other exotic communities, they were featured in stereoscope photographs intended to serve as both signifiers of worldliness in middle class parlors and conversation starters for those who had taken a trip to meet them. The most important collection of photographs of Samaritans, which circulated around the western world, were taken by the American colony photographers beginning in 1900, two years before Barton’s journey. These were not simply photographs of Samaritan life, as they are often assumed to be, but examples of a type of ethnographic portraits common at the time. The subjects’ positions and the staging of the photographs resemble, for example, those of well-known ethnographic photographers such as Edward S. Curtis’ work on Native Americans. Often set at biblical sites such as Jacob’s Well and Joseph’s Tomb, they were intended to portray both the greatness of the Samaritans’ biblical past as well as their impoverishment in the present, in the same tragic mode adopted by Twain and Warren. Photographs are often taken at angles, such as profiles, that were commonly used by ethnographers to classify racial types. Jacob son of Aaron, who became an admired figure among westerners with interest in the Samaritans, was a frequent subject of these portraits, a handsome man whose middle eastern features and luxuriant beard made his image a compelling feature in western newspapers and magazines. The Samaritan Passover sacrifice also became a focus for ethnographic photographers and remains so to this day.

Barton and Warren believed that they could use this interest in the Samaritans as part of their efforts to raise money for the community. To this end, they commissioned an American Colony photographer to take a series of photographs of the Abisha scroll with the intention that the resulting images could be a resource for libraries and universities. An important textual scholar at the time identified the scroll in the photographs as a later copy of the Abisha scroll rather than the original and this plan failed.

It is unclear what plans Barton and Warren had for the artifacts they gathered. It seems from correspondence exchanged between Barton and Frederick W. Chamberlain, Warren’s executor and brother-in-law, after Warren’s death, that Warren had planned to exhibit these artifacts in a museum in Nablus geared toward raising money to help support the Samaritan community. When Chamberlain and Barton later determined that there were not enough funds in the American Samaritan Committee’s coffers to fund such a museum, they feared that any artifacts remaining in the Holy Land might be claimed by the Samaritan community. To avoid losing the artifacts, they brought them back to the United States. The Samaritan community tried to have the artifacts returned, citing Warren’s plans, but Barton and Chamberlain decided that the objects would be better preserved in an American institution. They were subsequently displayed for some time in the Warren family museum but in 1950 the Warren family closed the museum, and the Samaritan items were given to Michigan State University in Lansing. According to the late Michigan State Professor of Bible Robert T. Anderson, who wrote about these materials in several scholarly articles and books, the collection was placed in cardboard boxes in a storage area beneath the football stadium, where they remained until discovered by Anderson during a renovation of the stadium in 1968.

The Samaritan community seems to have appreciated the support of Barton and Warren’s Committee but wanted to be more involved in administering the funds collected and the manuscripts purchased. Samaritan high priest Jacob son of Aaron wrote the text for several of the committee’s circulars and ads placed in Christian publications. In one such undated circular he appeals to his American readers to help the Samaritans fulfill the biblical obligation of “Keep therefore the words of this covenant,” a savvy choice of verses for an audience who saw the Samaritans as a link to a preserved biblical past.

With Warren’s death in 1919, and the end of the First World War, Barton’s interest in the Samaritans waned. The next year, he and Chamberlain decided to cease the American Samaritan Committee’s operations (though they never formally disbanded it) and distributed its small reserves to the community for its own use. This came precisely at the moment when the Samaritan community, decimated from the wartime military draft and the scarcity of the war years, needed help most. The decline of American interest in the Samaritans at this time may have been in a large measure to the popularization of James Montgomery’s thesis in his classic 1907 history of the Samaritans that the latter were merely a sect of the Jews that had broken away during the Second Temple period rather than the scions of the ten tribes. By implication, this meant that there was very little the Samaritans could tell American Christians about the true nature of Judaism or of Christianity’s roots.

As biblical scholar James Purvis notes in a 1969 article about the Barton Collection, the tone Barton and Warren took to the Samaritans after World War I became increasingly patronizing and condescending. During the war, the Committee learned that the school they had funded had been closed and copies of the photographs of the Abisha scroll taken by John Whiting of the American colony had never been given to the community as promised. Members of the Samaritan community claimed that Whiting, who also served as the American Samaritan Committee’s feet on the ground in Palestine, had led the Samaritans to believe that the Colony or Committee would support them during the hardships of the war years in exchange for the photographs. In a letter to Warren’s son, Barton voiced frustration with Whiting but more so with the Samaritans:

My own present judgement would be that not too much attention should be paid to it [the Samaritans’ claims against Whiting]. They are a childish people, with a covetousness and quarrelsomeness in their childhood and much has been done in recent months to stir up all manner of misunderstanding and bitterness. I do not wonder that Mr. Whiting is out of patience with them.

(Letter from Barton to Paul C. Warren, March 13, 1919)

Samaritan claims that Warren’s agent had not paid them in full for several manuscripts, including the Chamberlain-Warren Pentateuch, as well as their desire to keep Warren’s artifacts in Nablus went unheeded. Writing to Warren’s son, Barton said he doubted Warren had left any outstanding debts and that they could perhaps give the community a small amount as a final payment. “Nevertheless,” he wrote,

I cannot help thinking that it would be better to bring that manuscript to this country and hold it until its future can be secured. If the Samaritans under claim of amount due on it [sic] should recover it they would quickly mortgage or sell it again.

(Barton to Paul C. Warren, June 2, 1919)

In June 1920, the Committee met and resolved that they would not try to reopen the school and that:

The hope of Mr. Warren that a Museum might be established at Nablus and a tract of land purchased for the Samaritan Committee appeared to the committee to be matters which the changes brought by the wart had put well out of the foreground of probable events.

(Minutes of the American Samaritan Committee, June 10, 1920)

In 1922, a group of leaders of the Samaritan community, including the new high priest, Isaac son of Amram, sent a letter via the English governor of the Nablus subdistrict to the treasurer of the American Samaritan Committee asking that they be returned. They made special mention of the ancient Pentateuch manuscript. Barton insisted that the Samaritan claims had no merit, writing that after the war the Committee had tried to continue to help the Samaritans. Whiting had, however, been “so disappointed in their reception of aid that it did not seem practicable to go forward with anything more than the completion of the undertakings commenced in Mr. Warren’s life.” When the Committee sent a token sum in an effort to settle the dispute, the Governor wrote back that the community had refused to accept it.

In the early twentieth century, American popular writers and educators like Barton hoped the Samaritans would answer their questions about biblical Israelite religion. They and their rituals, and to a large degree their racial makeup, were described as “unchanged.” For most American Christians, however, Samaritans remained an abstract concept, protagonists of biblical stories or the namesakes of hospitals and charities, rather than a modern people. The American Samaritan Committee and similar efforts to raise funds for the Samaritans combined both of these perspectives. Barton seems to have ultimately been unable to come to terms with modern Samaritans being more than just objects of fascination and ethnography.

Excerpted from “The Samaritans: A Biblical People,” edited by Steven Fine. Published by Brill © 2022. This volume is an accompaniment to a traveling exhibition, on view at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., September 15, 2022-January 1, 2023.

Yitzchak Schwartz is a historian whose work focuses on popular American ideas about religion.