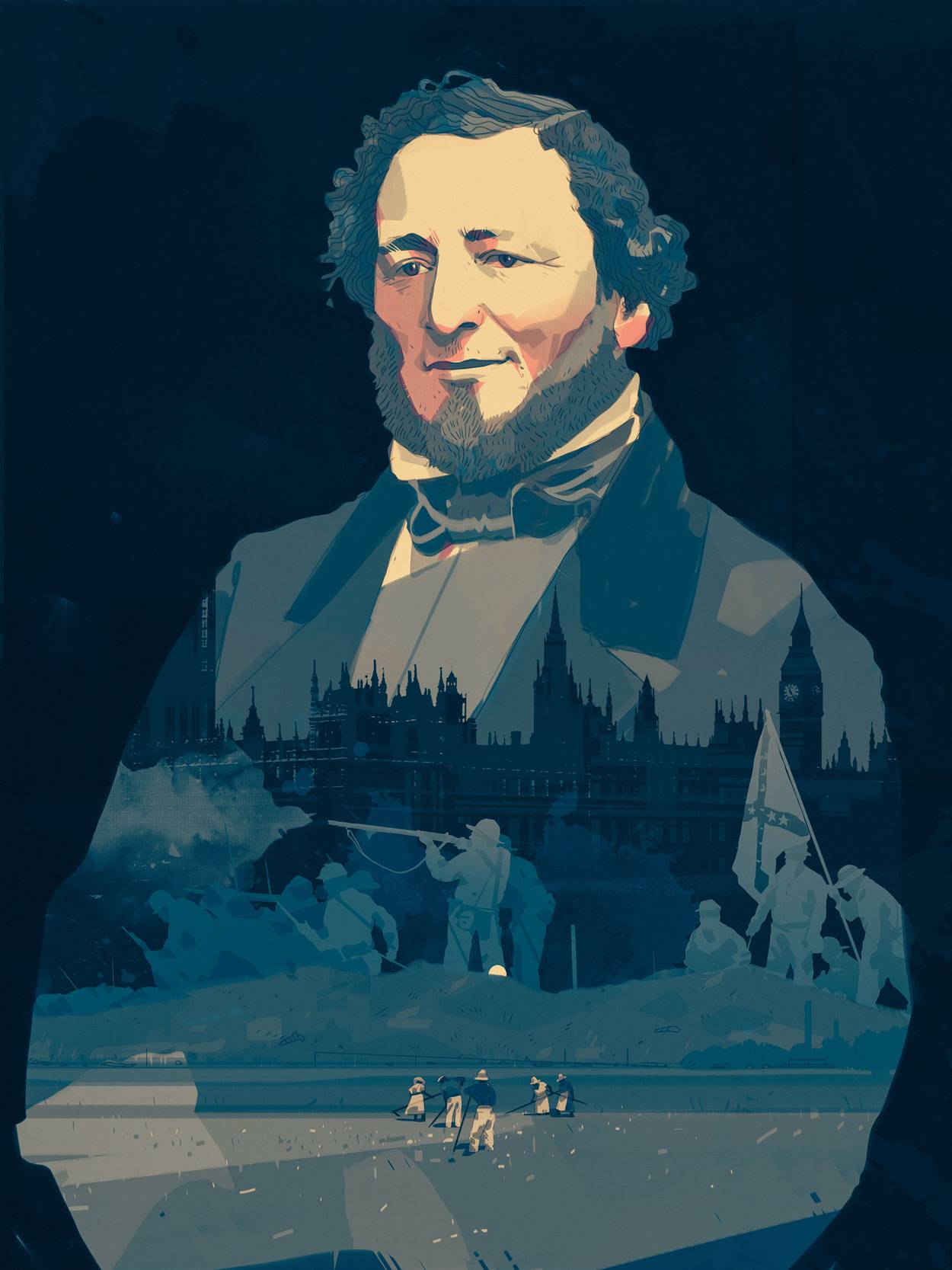

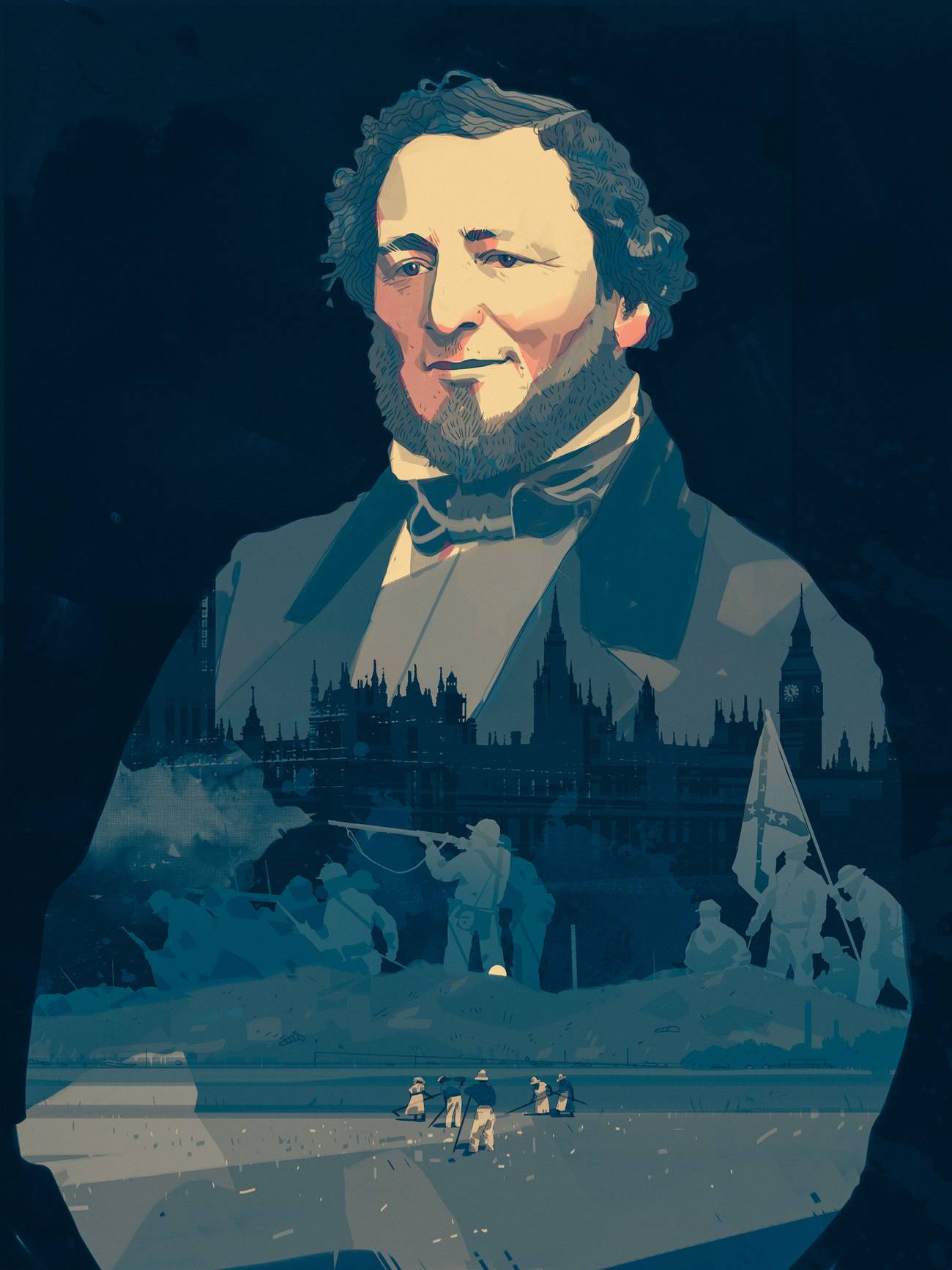

Two years after the Civil War’s guns went silent, the former Union General George H. Sharpe navigated London’s bone-biting cold and snowy rail lines to reach the U.S. diplomatic mission at 54 Portland Place. His orders from Washington were both secret and explosive: Capture the former secretary of state of the Confederacy, Judah Philip Benjamin, who’d found exile, and a lucrative law practice, in Victorian England.

The New York-born Sharpe had been chosen for the operation for good reason. He’d overseen military intelligence for Union Commander Ulysses S. Grant during the final stages of the war between the states and emerged as a special envoy for U.S. Secretary of State William Seward in its aftermath. Sharpe had run espionage operations into Richmond, the Confederate capital, and Benjamin’s base of operations.

But Sharpe’s trip to England that February was on a particularly grave matter, and unknown to the American public. Senior members of the U.S. government, including Secretary of State Seward, believed there was ample evidence that Benjamin had played a central role in developing the plot to assassinate Abraham Lincoln two years earlier.

Benjamin’s network of Confederate spies and couriers ran from Virginia, up through the Northern states, and into Canada. And this secretive web directly tied the prominent Southern Jewish leader to members of the hit team that organized the attack on Lincoln and Seward in April 1865. This included John Wilkes Booth and his accomplice, John Surratt Jr., a Southern spy who had worked as Benjamin’s personal courier.

U.S. authorities were determined in the winter of 1867 to bring Benjamin to justice along with the former Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who was imprisoned at Fort Monroe, Virginia, with a pending trial for treason. If convicted, Davis would face the death penalty, as would Benjamin.

Once inside the U.S. mission in London, in a dusty basement piled with dispatches, Sharpe took into his confidence the No. 2 official in the American mission, the diplomat and political gadfly Benjamin Moran. Sharpe disclosed to the startled bureaucrat that he’d been ordered by Seward to hunt Confederate leaders who’d fled to England, France, and Italy after the war. This included John Surratt, who’d made a serpentine escape from the U.S. through Canada and Europe before finally being captured in Alexandria, Egypt. He was indicted for his alleged role in Lincoln’s murder and set to go on trial in Washington, D.C., just a few months later.

Moran took copious, handwritten notes of his conversations with his visitor from Washington. “Mr. George H. Sharpe, a detective, has been sent here to hunt up evidence against persons implicated in the assassination of Mr. Lincoln,” Moran wrote on Feb. 11, 1867. “[Sharpe] is a bullet-headed fellow and is determined to catch Benjamin if possible.”

A week later, Moran scribbled again in his diary, “General Geo. H. Sharpe called. He thinks he will be able to prove that Judah P. Benjamin was implicated in the assassination of Mr. Lincoln. I hope so …”

Judah Benjamin is perhaps the least known of the senior Confederate leaders who fought to carve out an independent nation from 11 Southern states in the 1860s. An affluent Louisiana attorney, plantation-owner, and politician, he served in a number of critical posts in the Confederate cabinet during the four-year war. These included: attorney general, secretary of war, and secretary of state. Benjamin’s Jewish faith set him apart in a Confederate movement that promoted and idolized white supremacy, chattel slavery, and a feudal planter culture born out of European colonial settlement. Yet he supported all of these things.

Benjamin’s Jewish faith set him apart in a Confederate movement that promoted and idolized white supremacy, chattel slavery, and a feudal planter culture born out of European colonial settlement. Yet he supported all of these things.

Benjamin’s life had myriad chapters and was spectacular in its scope. He was born on Aug. 6, 1811, into a family of Sephardic Jewish traders in the British West Indies, but settled in Charleston, South Carolina, as a toddler. Blessed with an exceptional intellect, he enrolled at Yale University at just 14, before being expelled under mysterious circumstances.

He moved to New Orleans and reinvented himself as a lawyer, politician, and planter in a teeming colonial city that mixed French, Spanish, and British cultures and legal systems. He married into a Catholic Creole family and established himself in the Southern aristocracy by purchasing a massive sugar plantation with 140 slaves.

In the months leading up to the war, Benjamin, a U.S. senator representing Louisiana at the time, was among the South’s most ardent and impactful defenders. Up until his final days in Washington, he warned the U.S. government about the costs of the looming conflict.

“You may, under the protection of your advancing armies, give shelter to the furious fanatics who desire, and profess to desire, nothing more than to add all the horrors of a servile insurrection to the calamities of civil war,” Benjamin boomed from the Senate floor. “You may do all this—and more, too, if more there be—but you never can subjugate us. You never can convert the free sons of the soil into vassals … Never! Never!”

Historians have often referred to Benjamin as the “Brains of the Confederacy” and President Jefferson Davis’ closest, and most reliable, civilian adviser. Biographies about Benjamin that appeared in the decades following the Civil War often read as hagiography. They extol his legal mind, oratory skills and brilliance in running logistical operations. The general portrayal of Benjamin is of a loquacious and razor-sharp attorney and politician who charmed his interlocutors with his mind.

Benjamin, in his own words, described himself and Davis as effectively joined at the hip. The Louisiana lawyer was a central architect of the Confederate leader’s political and economic policies and the wordsmith behind many of his orations. “You knew my secrets,” Benjamin wrote his old friend and colleague, James Murray Mason, after the war. “I wrote many of President Davis’ speeches.”

All of these writings no doubt offer insights into the Confederate leader’s life and personality. And yet they omit one of the central roles Benjamin played during the Civil War: He was a spy chief of the South and oversaw the Confederate Secret Service that was embedded in Benjamin’s own State Department. He ran agents into Washington, New York, Boston, and other Northern cities, as was expected. But he also produced an early form of fake news, ordering Confederate emissaries in Europe to plant stories about fatuous Southern military victories into British and French papers. He also engaged in financial warfare: using Northern bankers to try and devalue the U.S. dollar through the export of gold.

But it was in the final two years of the Civil War where Benjamin’s espionage operations took a particularly dark turn. Desperate to fend off the collapse of the Confederacy, the Southern secretary of state put in place an elaborate network of spies and soldiers in British-controlled Canada to seek to destabilize the North. Benjamin’s agents robbed banks, attempted to burn down Manhattan hotels and devised ways to conduct chemical warfare in Washington. They also sought to upend the 1864 Republican Party convention and swing the vote against the incumbent president, Abraham Lincoln, in favor of a peace candidate who sought an immediate end of the Civil War.

And Benjamin’s agents in Canada also hosted in Montreal a famous actor from Maryland, John Wilkes Booth, during the final months of the war, and provided him monies and contacts to conduct a plot that initially focused on kidnapping Abraham Lincoln. It was for these activities, among other business, that retired General George Sharpe went to London in 1867 to search for Benjamin. And it’s the story of this mission that remains one of the great secrets of the Civil War.

By the spring of 1864, the fate of the Confederacy was largely sealed. Ulysses S. Grant had taken command of all Union troops and launched a slow, bloody siege on Richmond that would largely keep Southern troops pinned down for the final year of the war. The Union army also initiated increasingly aggressive operations to target Southern cities, civilians, and food supplies. For Davis and Benjamin, these tactics broke a supposedly genteel code of conflict that had ruled for the first three years of the Civil War.

That April, on the outskirts of Richmond, Davis’ men also stopped a particularly bold Union mission. It was led by a U.S. colonel, named Ulric Dahlgren. Confederate troops killed Dahlgren and found on his body orders, purportedly from Washington, directing his men to infiltrate the Southern capital and decapitate the Confederacy’s leadership by assassinating the entire cabinet, including Davis and Benjamin.

The two leaders were enraged by the plot and decided to retaliate by financing and empowering the Confederate Secret Service to conduct asymmetric operations against Washington and expand the South’s fight into Canada, which was then a neutral British territory. This, they believed, would force Lincoln and Grant to face a two-front war. The Confederate leadership hoped this expanded conflict could drain the Union’s resources and the North’s support for the war. It could also bring the British into the war–on the side of the South.

To lead the Canadian mission, Benjamin appointed a Mississippi plantation owner and former U.S. congressman named Jacob Thompson, who was a Southern hero. Thompson had served as interior minister in the last U.S. government before the Civil War and established the University of Mississippi in Oxford, the Yale of the South. But he was an odd choice to run a Confederate operation that mixed espionage and warfare. He had no formal military training or experience, though he was Jefferson Davis’ close childhood friend.

Read more about Jews and the Confederacy

Thompson secretly traveled to Canada in the spring of 1864 after receiving his orders in Richmond and established Confederate operations in Montreal, Toronto, and other cities and towns along the U.S. border. His primary headquarters was the Saint Lawrence Hall in Montreal’s old French quarter, where he often stayed with Clement Clay, Beverly Tucker, George N. Sanders, and other Confederate commissioners and operatives.

The city was crawling with British and American spies. But this didn’t stop the Confederates from launching their cross-border war. They believed it was perhaps their last chance to forestall a Northern victory.

Thompson’s Canadian operations ranged from the mundane to the spectacular. But they all suffered from a lack of manpower and competency and the fact that American intelligence had largely penetrated his network. Davis’ and Benjamin’s hopes that these plots would alter the course of the war wouldn’t be borne out.

Confederate agents traveled to Chicago in November 1864 to try and surreptitiously influence the Democratic convention and rally support behind the pro-peace candidate, onetime Union General George McClellan. Thompson’s agents briefly commandeered a Union warship operating in Lake Michigan. And former Confederate soldiers crossed the border into St. Albans, Vermont, to rob banks and terrorize the local citizenry.

Thompson’s most deadly operation involved infiltrating Southern rebels into New York with a form of inflammable liquid, called Greek Fire. The operation sought to simultaneously immolate 19 Manhattan hotels, as well as boathouses and the Barnum Museum. But the would-be arsonists failed to recognize that the Greek Fire needed oxygen to conflagrate and left the doors and windows of the hotels and buildings closed. The hotels simmered but didn’t burn, and the smoke allowed fire brigades to prevent the demolition the Confederates sought.

Thompson wrote Judah Benjamin from Canada in December 1864 and acknowledged the failings of his mission. He’d be replaced weeks later by General Edwin Gray Lee, a cousin of the Confederate commander Robert E. Lee. “I have relaxed no effort to carry out the objects the government had in view in sending me here,” Thompson wrote. “I had hoped at different times to have accomplished more, but still I do not think my mission has been altogether fruitless.”

The Confederacy explored even more radical plots as their military position vis a vis the North grew more dire. Edwin Lee’s agents in Canada devised a plot to spread yellow fever into Northern cities. And funds from Benjamin’s Secret Service in Richmond were disbursed in an effort to develop chemical weapons to bring “terror and consternation to Northern cities.” Benjamin’s close assistant, Littleton Quinton Washington, wrote later that both Davis and Benjamin didn’t think these attacks on noncombatants went beyond the bounds of “civilized warfare.”

One historical fact from the Canadian mission, however, would long outlive the Civil War, and haunt Confederate leaders like Benjamin. This was the trip to Montreal in October of 1864 by the Maryland actor-turned-assassin John Wilkes Booth. His presence in the colonial city, and meetings there, test the accepted conclusion that his plots to kidnap, and then murder, Abraham Lincoln were totally unknown to the Southern leaders.

Booth spent eight days in Montreal and was spotted in meetings with Benjamin’s agents at the Saint Lawrence Hall, as well as in bars and restaurants across the city. Booth’s stay appeared to be both a recruitment and training exercise. He was wooed by the Confederate Secret Service and instructed on the types of actions he could take to further their cause.

The actor’s presence didn’t go unnoticed to Americans visiting Canada that fall. “I met this man Booth in Canada last fall, at Montreal, at the Saint Lawrence Hall,” said John Deveney, a reliable Northern witness who visited Canada, and testified against Booth after the war. “He was then in the company with Sanders, Thompson, and others of that class. He seemed to be well-received by these men and was on familiar and intimate terms with them.”

Indeed, these Confederate agents directly prepared Booth for his covert operations against the Union. Hiram Martin, a blockade-runner, took Booth to the Bank of Ontario on Oct. 27, the morning of the actor’s departure for the U.S., according to eyewitnesses and documents. They opened a bank account in Booth’s name and deposited $455. They also purchased a bill of exchange, technically a traveler’s check, for 61 pounds, 12 shillings and 10 pence.

“The funds on deposit would give Booth a nest egg if he needed to make a hasty retreat across the border to Canada, a notion that had already crossed his mind,” the historian Terry Alford wrote about Booth’s Confederate financing.

Martin also provided Booth with helpful letters of introduction to rebel agents living in southern Maryland and the Northern Neck of Virginia. These men and women would be based along the escape route the actor would take if he made good on his plan to abduct President Lincoln and spirit him to Richmond. An extensive underground of agents existed, some of whom reported directly to Judah Benjamin, and were awaiting Booth and his accomplices.

Booth didn’t totally turn his back on the theater while in Canada. One night in Montreal he wooed locals at the city’s popular Corby’s Hall by reading passages from Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice and Alfred Tennyson’s Charge of the Light Brigade. His renditions were greeted with thunderous applause.

He didn’t disguise his contempt for President Lincoln while carousing in Canada either. One night at the Saint Lawrence Hall, he intimated to a fellow guest that the American leader’s days were numbered. “For Abe’s contract was near up and whether reelected or not, he would get his goose cooked,” Booth told his interlocutor, who recounted the exchange in a letter he wrote to the Hamilton Times after Lincoln’s assassination months later. The letter was republished in The New York Times.

Just six months after John Wilkes Booth’s covert trip to Montreal, the Confederacy fell, and Judah Benjamin’s life took another dramatic turn. On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House. Then-acting provost marshal General George Sharpe officially paroled Lee’s troops and mandated they be allowed to return to their homes in the South unmolested. Just a week later, Booth assassinated President Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre, morphing his original kidnapping plot into one of history’s most consequential murders.

Benjamin, Jefferson Davis, and the Confederate leadership fled south after Richmond’s collapse and were temporarily based in Charlotte, North Carolina, when news arrived of Lincoln’s death. No concrete evidence has emerged in the historical record that conclusively proves Benjamin or Davis had any knowledge of Booth’s murderous plans. But as the newly victorious North sought vengeance after four years of fratricidal war, Benjamin, for one, knew he’d be a suspect due to his ties, through the Confederate Secret Service, to the actor-turned-assassin.

Union detectives investigating Lincoln’s death quickly reconstructed Booth’s travels to Montreal and the contacts he’d made there with Benjamin’s agents. But even more damaging to the Confederate diplomat, they also found in Booth’s hotel room a Confederate cipher key that exactly matched one they found in Benjamin’s abandoned Richmond office. This evidence was presented at the trial of the Lincoln conspirators in Washington.

“On the 6th of April, I went into the office of Mr. Benjamin, the rebel Secretary of State. On the shelf, among Mr. Benjamin’s books and other things, I found this cipher key,” testified Charles Dana, the North’s assistant secretary of war. “I saw it was a key to the official rebel cipher.”

Benjamin’s spy network also tied him to Booth in other damaging and seemingly direct ways. While serving in Richmond, Benjamin used as his personal courier a Maryland-based rebel, John Surratt Jr., to ferry his messages to Washington and agents further north. It was the same man who served as Booth’s accomplice in concocting the kidnapping plot of Lincoln. Surratt’s mother, Mary, hosted the actor at her Washington boarding house in the weeks before the attack.

Surratt would later speak of meeting Benjamin at Richmond’s Spotswood Hotel, and receiving money from him, just days before the capital fell and the attack on Lincoln commenced. Surratt denied ever telling Benjamin of Booth’s activities. But the Confederate leader’s intelligence, and expansive control of his Secret Service, raises questions about the truthfulness of Surratt’s statement. Mary Surratt was eventually hanged for her role in supporting Booth. John Surratt escaped the U.S. by using Benjamin’s overseas spy networks to get to Europe.

Benjamin, meanwhile, commenced after the assassination of Lincoln to launch one of the greatest escapes in American history—especially for a bookish, pudgy attorney with no military service. He peeled off from Jefferson Davis’ entourage in the town of Washington, Georgia, on May 3, 1865, and proceeded to make his way down the Gulf Coast of Florida. He disguised himself as a bearded, and disheveled, French trader, named M.M. Bonfals, according to press accounts from the time. “Goggles on … a hat well over his face,” Benjamin was nearly unrecognizable.

He bumped along in a wagon on long, rutted roads and passed by the detritus of the war, including burnt-out buildings and scorched fields. He made it to a sugar plantation owned by a Confederate sympathizer in what’s now Bradenton, Florida. He hid for a month from Union patrols in the plantation house’s second story. He eventually found a Confederate spy ship to ferry him to the Bahamas. But he nearly drowned in subsequent attempts to reach Cuba, dogged by waterspouts and unseaworthy sloops. It took him weeks to reach Havana and the steamships that crossed the Atlantic.

The Union government’s obsession with capturing Benjamin, however, only grew as the trial of the Lincoln conspirators commenced in May 1865. Newly sworn in President Andrew Johnson, a rabid antisemite, told the Northern press: “There was no rebel, whose hanging seemed so imperatively demanded by public justice, as Judah P. Benjamin.”

Newly sworn in President Andrew Johnson, a rabid antisemite, told the Northern press: ‘There was no rebel, whose hanging seemed so imperatively demanded by public justice, as Judah P. Benjamin.’

The Confederate spy chief finally reached Southampton, England on August 30, 1865, more than four months after Richmond’s fall. He would immediately tap into the Confederate networks in England and France that he was so central in creating and deploying. He had allies across the sea.

The England in which Judah Benjamin arrived that summer had played a supremely duplicitous role in the American Civil War, a point not lost on the newly victorious U.S. government. Officially, Queen Victoria’s government had been neutral, and her diplomats sought to orchestrate peace between North and South. But at the same time, London’s actions undoubtedly fueled the conflict and aided a Confederacy that was far outgunned by Northern military manpower and munitions. England, concerned about a former colony emerging from the war united, resource-rich, and with global ambitions, seemed content on prolonging the war.

British leaders often spoke admirably of the Confederacy as it took root and won key early battles at Bull Run and Seven Pines. William Gladstone, the chancellor of the exchequer, said of the rebels in 1862: “We may be for or against the South, but there is no doubt that Jefferson Davis, and other leaders of the South, have made an army … They have made a nation.”

Benjamin’s emissaries quickly set up shop in London and Liverpool as the war gained momentum, making the latter the Confederacy’s de facto European capital. Liverpool’s docks, under the watchful eye of the Southern agent, James Dunwoody Bulloch, became a center for the Confederacy’s war-making activities, despite Britain’s claims of neutrality. There the rebels produced blockade runners and commerce raiders, like the CSS Alabama, which wreaked havoc on the U.S.’s Merchant Marine navy. Bulloch also traded Southern cotton for British-made Ensign rifles and military uniforms.

In London, Benjamin also placed the Swiss American propagandist, Henry Hotze, to run and edit the pro-Confederate newspaper, The Index, from the heart of Fleet Street. This weekly publication sought to win over British public opinion, as well as others in Europe, by playing up the South’s military advances, if not inventing them, and highlighting the ill effects of the Union blockade on England’s expansive textile industry. Hotze also promised in his paper’s pages that the Confederacy would be a better trade partner for Europe than the North, due to low tariffs, and appealed to European liberals to recognize the Southern people’s rights of self-determination.

Benjamin immediately tapped into this Confederate infrastructure after arriving in England in 1865. Though the war was lost, his agents still maintained prime real estate in Victorian England, close to the royal seats of power. The South’s secretary of state first found shelter in London at 17 Savile Row, appearing unannounced at the Confederate Commercial Agency run by Henry Hotze. The four-story row house was located just blocks from the Regent Street estate of Lord John Palmerston, the prime minister. Buckingham Palace was also only a few blocks away.

Central London was cluttered at the time with other Confederate offices and organizations that had been established to conduct trade and effect perhaps Benjamin’s most important aim during the war—winning British diplomatic recognition of the South. Such a step, he and Jefferson Davis believed, would have essentially ended the conflict. Southern ambassadors lived on Half Moon Street in the wealthy Mayfair district. And the headquarters of the Southern Independence Association, which had 47 offices across England, was based at Connaught Place and lobbied members of Parliament to the Confederate cause.

Benjamin showed foresight before fleeing Richmond ahead of Union troops, shipping cotton to England to give himself immediate access to cash. But, at 54, he still needed to establish himself professionally in Europe and provide for his family, and wife and daughter, who lived in Paris. He initially earned some revenue by penning columns on international affairs for the Daily Telegraph. But his main focus was to return to the law and the affluent lifestyle he had attained in New Orleans and Washington.

Thanks to powerful benefactors in England, Benjamin would quickly gain admittance into Britain’s premier legal society at the Inner Temple complex near the walls of London’s Old City. He’d be called to the bar in just over a year after his arrival in the country, an extraordinarily short time. A formally accredited barrister, Benjamin was now fully integrated into elite British society.

He first employed his legal prowess in England’s “Northern Circuit” of courts, which included the Confederate stronghold of Liverpool. It wasn’t long before he was representing Southern interests against a U.S. government determined to expropriate the assets of its mortal enemy, both in America and abroad. In an early case, Benjamin successfully defended a Confederate agent, named Colin McRae, against a U.S. effort to seize his lands in Alabama.

In 1867, Benjamin then appeared in a London court as counsel for the Confederate finance company Fraser Trenholm & Co., which was facing another U.S. government effort to seize Southern assets overseas. South Carolina-based Fraser Trenholm grew rich in the antebellum South trading cotton to Europe. But during the Civil War, it financed the building of most of the Confederacy’s warships from its office at 10 Rumford Place in Liverpool. The building was situated just across the street from Liverpool’s docks and served as an unofficial rebel embassy.

The American public was stunned, if not outraged, when Benjamin suddenly reappeared in local newspapers to battle the U.S. government once again. This time, in the courts. It was almost as if the lawyer was taunting his enemies in Washington from across the Atlantic.

“Bayard Taylor [an American writer and diplomat] was in London on the 27th and the 26th … in expectation of hearing a renewal of the [Fraser Trenholm] trial,” read a March 1867 article in the Memphis Daily Avalanche. “He stood shoulder-to-shoulder for a few minutes with the ex-rebel secretary of state, Judah P. Benjamin, now a full-blown English barrister, bewigged and begowned.”

General Sharpe covertly arrived in London that winter just weeks before Benjamin’s court appearance, under the orders of U.S. Secretary of State William Seward. Seward and Benjamin had been fierce diplomatic opponents during the Civil War, holding the same, opposing cabinet posts. But their fractious relationship went far deeper, played out over decades, and was driven by ideological differences and a personal animosity.

Seward and Benjamin both served multiple terms in the U.S. Senate and envisioned starkly different futures for their country. Seward was a fervent abolitionist from Auburn, New York, whose home was used as a stop along the Underground Railroad. A lawyer, he defended former slaves against murder charges and advocated for the end of the “peculiar institution” of slavery through any means possible.

Benjamin, conversely, had owned a massive sugar plantation east of New Orleans, called Belle Chasse, which maintained over 100 slaves. He was also one of the Senate’s most ardent and articulate defenders of “states’ rights,” a legal and political philosophy that justified slavery as a core engine driving the South’s agrarian economy. It was a rallying cry for the 11 Southern states that ultimately seceded from the U.S. in 1861. According to Benjamin’s biographer, Eli Evans, Benjamin and Seward “hated each other on sight” upon their arrivals in Washington.

Seward nearly lost his life during the final chapter of the Civil War. Before killing Abraham Lincoln, John Wilkes Booth dispatched his accomplice, a former rebel soldier named Lewis Powell, to Seward’s home in Washington to assassinate the chief U.S. diplomat. Powell failed in his mission, but he did slash Seward multiple times, permanently disfiguring his face. Powell also broke the skull of the Union leader’s son, Frederick. Seward’s wife, Francis, never recovered from the emotional and mental trauma caused by the attack and died within months.

Seward sent General Sharpe to London on the mission to find any Confederate leaders in Europe who were potentially involved in the plot against himself and Lincoln. But Seward seemed to be particularly focused on Judah Benjamin, his old nemesis. For the U.S. secretary of state, this was personal.

General Sharpe chose Benjamin Moran, the No. 2 American diplomat in the U.S.’s London legation (a precursor to an embassy) to help him pursue Benjamin. Moran had served in the mission for 15 years and was an outspoken critic of the Confederacy, who mandated that all former rebels based in Europe needed to swear allegiance to the U.S. government before reclaiming their passports and returning home. As a side business, he once co-owned the British magazine the Spectator, which sought to promote support in Europe for U.S. policies.

Moran took copious notes in his diary of his dealings with Sharpe in the winter and spring of 1867. These diaries have been almost totally overlooked by Civil War histories to date. A few short mentions have appeared in biographies of Judah Benjamin and George Sharpe. But there’s no reference of Sharpe’s hunt for Benjamin in the archives of the British government, including its Home Office, Foreign Office, and Scotland Yard. This is the most complete accounting of the mission, and the reasons behind it.

Moran first writes of Sharpe’s arrival in London on Feb. 11, 1867, the first of three months of diary entries focused on the general-turned-detective’s activities. The description of Sharpe’s task is straightforward and clear—to capture Benjamin. And Moran initially sounds confident in their prospects for success. On February 18, for instance, Moran writes: “General Geo H. Sharpe called. He thinks he will be able to prove that Judah P. Benjamin was implicated in the assassination of Mr. Lincoln. I hope so…”

Moran doesn’t describe in these early entries how Sharpe planned to capture Benjamin, or what he’d do if he’s successful. It’s likely that his plan involved snatching Benjamin off the streets of London through a rendition. But these U.S. officials must have known they faced major challenges in trying to bring the Confederate leader back to the U.S. through formal legal channels in England. Benjamin had been born on the island of St. Croix in the British West Indies. And upon arriving in England in 1865, he successfully petitioned the government to classify him as a British subject, due to his place of birth.

One avenue the Americans could have pursued was to seek Benjamin’s extradition through the U.S.’s Webster-Ashburton Treaty with England. But its terms were stringent. Extradition of a British citizen wasn’t granted on charges of accessory to murder, or conspiracy to commit murder. Sharpe needed to show that Benjamin was directly involved in Lincoln’s death, not just tied to it through John Surratt Jr. or the Confederate Secret Service. This was an extremely high bar.

Moran and Sharpe, in the ensuing weeks, took to the streets of London and sought to retrace the steps of Benjamin and other Confederate exiles. They also did some sightseeing at the British Museum. On March 5, Moran goes to London’s prestigious Fenton’s Hotel to ask if Benjamin had stayed there after his escape. “They had no record of the fact in their book,” Moran wrote. “The doorkeeper, however, said he was there.”

Sharpe, meanwhile, was tracking George McHenry, a Confederate commercial agent based in Liverpool, who had been active in Benjamin’s and Henry Hotze’s Southern propaganda efforts in England. McHenry’s brother, James, was a Union supporter and close friend of Benjamin Moran’s. McHenry may have had information on Benjamin’s whereabouts and activities. On March 14, Moran writes: “General Sharpe came up. He is on track of George McHenry and thinks he will be successful.”

But soon, the confidence of the early entries ebbs. Beginning in March, the two men begin enquiring about the prospects of them employing Jonathan “Jack” Whicher of Scotland Yard to aid in their efforts to find Benjamin. Whicher was one of the detective agency’s eight original sleuths and had gained national fame after discovering the murderer of a young British boy. On March 16, after several failed attempts to reach Whicher, Moran writes: “Met Sharpe at the Langham [Hotel] … Drove to Mr. Whicher’s house, 63 Page Street, Westminster … arranging with him for his services to ascertain if J.P. Benjamin saw John H. Surratt and supplied him with money after Mr. Lincoln’s assassination. He will probably undertake the work.”

But there’s no evidence that Whicher ever joined the hunt for Benjamin. Instead, Whicher was paid a large sum to unmask an impostor posing as an heir to a British fortune, a case that also caught the British public’s imagination. Sharpe’s search for the Confederate leader, meanwhile, appeared to go cold. The general left London for Rome to try and learn more about the escape of John Surratt to Europe. Benjamin’s onetime courier had been captured in Egypt and was now facing trial in the U.S. for his suspected role in the Lincoln assassination.

Moran’s last major entry on Sharpe appears on May 7, 1867, and doesn’t mention Benjamin at all. Sharpe returned to the U.S. just weeks later. “General Sharpe has just got back from Rome, brought one passport here used by Surratt to get into the Papal States, and I compared it with the copy he had made,” Moran writes. “Surratt used the name of John Watson.”

Sharpe remained an important political player in the U.S. in the years following his European mission. He was named a delegate to the 1868 Republican Party national convention and campaigned aggressively to place his military mentor, Ulysses S. Grant, in the White House. Grant, in turn, named Sharpe the U.S. marshal for the Southern District of New York, where he combatted political corruption and the “Boss” Tweed ring.

Sharpe only once publicly discussed his 1867 trip to England and other European countries. He wrote a letter to Secretary of State Seward that July, which was later shared with Congress and President Andrew Johnson. Sharpe, strangely, never mentions Judah Benjamin in the report or addresses the suggestions made in Moran’s diary that the retired American general was seeking to “capture” the rebel secretary of state in London.

Instead, Sharpe largely focuses on his investigation into John Surratt’s escape to Europe after Lincoln’s assassination and the search for any evidence that Confederate exiles in Europe aided the Southern rebel in his flight. Sharpe’s letter seems to exonerate these overseas Confederates of any role in a crime. “I have to report that, in my opinion, no such legal or reasonable proof exists in Europe of the participation of any persons there, formerly citizens of the United States, as to call for the action of the government,” the report reads.

Judah Benjamin went on to have a spectacularly successful second life in England and became one of the country’s most powerful and affluent barristers. To this day, Benjamin’s legal theories on commercial trade are used in the British court system. His “Benjamin on Sales” is a judicial bible. He was honored by Britain’s elite legal society at the Inner Temple shortly before his death in 1884.

But there’s evidence in the public record that William Seward and George Sharpe never completely cleared Judah Benjamin of playing a role in the Lincoln assassination, at least in their minds. The legal barriers to extraditing him from Europe were huge. On April 8, 1870, the New York Herald, one of the U.S.’s largest dailies, ran an article about Sharpe’s swearing-in as the U.S. marshal for the Southern District Court of New York. The story included this passage on Sharpe’s secret trip to Europe three years earlier:

“General Sharpe was sent by the government to Europe on the highly important and delicate mission of investigating the numerous representations being made to the State Department implicating prominent Confederates abroad in the assassination of President Lincoln,” the article reads. “The General’s real mission was concealed by an impression given to the public that he was on the Surratt affair, at Rome, and this is probably the first time that the public has been informed of the true object of his secret expedition at that time.”

It went on to read: “His report, which was very elaborate, vindicated all prominent Confederates except one from the charge of complicity in the assassination of President Lincoln, and in this case there was not sufficient evidence to justify an appeal to the extradition laws.” It was obvious the “one” was Judah Benjamin.