The Palestinian Vaccine Fiasco

How a political, media, and activist failure is leading to avoidable deaths

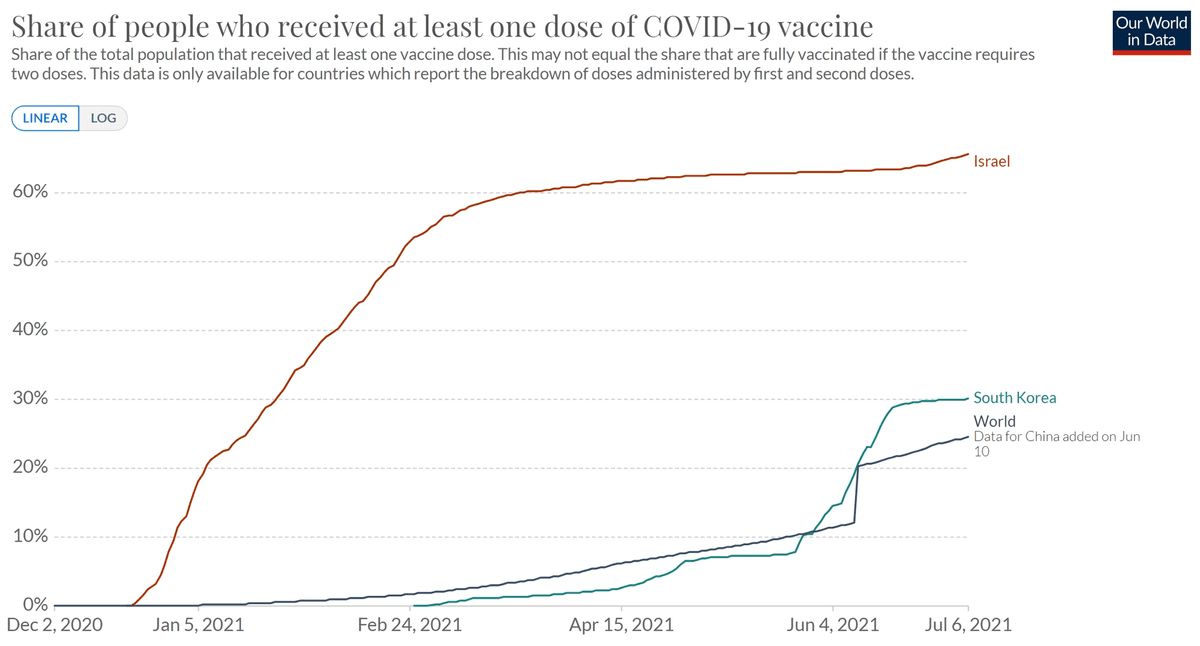

On Wednesday, an Israeli plane landed in Seoul carrying 700,000 Pfizer coronavirus vaccines. The batch was part of a strategic swap between the Jewish state and South Korea. The doses involved were due to expire at the end of the month, which meant that they would have likely gone to waste in Israel—whose population is mostly vaccinated—but would be quite valuable in South Korea, which is struggling to raise its relatively meager vaccination rate. And so, in exchange for Israel’s vaccines, South Korea agreed to trade its upcoming Pfizer order—estimated to arrive between September and November—to Israel. In this way, both countries will get what they need when they need it most.

The exchange is a win-win for Israel and South Korea—and a lose-lose for the Palestinian people, who were originally supposed to receive these very vaccines in the exact same arrangement with Israel. But thanks to a bad faith anti-vax campaign—enabled by feckless political figures, inept international media coverage, and partisan activism—the deal was capsized shortly after it was announced.

This public health disaster deserves a lot more attention than it has received, because it reveals the pathologies that continue to prevent progress in the region, and because, quite simply, it’s going to get people killed. If policymakers want to prevent that from happening, and stop fiascos like this from repeating themselves, they need to understand how this one transpired.

The sordid story begins last month, when Israel’s newly installed, anti-Netanyahu government managed to finally do something Bibi had either been unable or unwilling to do: provide vaccines to the Palestinian Authority. This course of action had been recommended by Israeli health officials for months, not to mention human rights groups, but Netanyahu never delivered. His successors did. On June 18, Israel’s new government announced a deal to transfer 1.2 million Pfizer vaccines to the Palestinian Authority, in exchange for a future vaccine shipment that was set to arrive in October.

It was an overdue arrangement that would save many Palestinian lives. Netanyahu had reportedly been “negotiating” such an agreement for some time, but never pulled the trigger, perhaps because he worried that it would undermine his standing among his base while he tried desperately to cling to power. The new government had no such qualms, and its health minister, Nitzan Horowitz—head of the leftist Meretz party—thanked his Palestinian counterpart and said he hoped that the agreement would lead to future Israeli-Palestinian cooperation on other fronts. Coming in the very first week of the new Israeli government’s tenure, the exchange seemed like a tangible if token example of what was possible in a post-Bibi world.

But the deal was short-lived. Mere hours after it was announced, the Palestinian Authority abruptly canceled the entire arrangement. The official reason was that the initial batch of 100,000 vaccines were too close to their expiration dates. The real reason was that they had received extremist backlash on social media over working with Israel.

The conspiratorial notion that Israel deliberately sent unusable vaccines to the Palestinians would later be exposed by events, after both Israelis and South Koreans happily made use of the doses. But it was obviously a lie at the time. The vaccine swap had been in the works for months, and every detail had been carefully vetted by the Palestinian Authority, including the expiration dates. As noted, the entire purpose of the arrangement was to swap soon-to-expire doses for distant doses, so that each population would have vaccines when they most needed them. Naturally, Israel first sent over the doses that expired that month, so that they could be immediately administered. This wasn’t a bait-and-switch, it was the plan. It was a feature—spelled out in the official Israeli statement announcing the deal—not a bug.

But this arrangement was not explained to the Palestinian population, which allowed extremist and anti-vax elements to turn the public against the supposedly subpar “Israeli vaccines”—a campaign which was no doubt helped by preexisting levels of vaccine hesitancy among Palestinians. Local social media began overflowing with protests against the agreement, and rather than explain how it worked, the Palestinian leadership folded immediately. Of course, had the real issue been the expiration dates of the first batch of vaccines, the obvious solution would have been to renegotiate the deal to exclude them. But that was not the real issue, and so the entire deal was called off.

If this depressing tale of capitulation to extremists sounds familiar, it’s because it is—on the Israeli side. As I wrote back in 2018, after Netanyahu struck and then tore up an agreement with the United Nations to resettle Israel’s African asylum seekers, the Israeli leader would often take “what he knew was a positive outcome for Israel and its values and punt it for short-term political gain.” Simply put, rather than stand up to his country’s racists and reactionaries—on asylum seekers, Palestinian vaccination, religious pluralism, and much else—Bibi frequently gave them a veto.

With Netanyahu out of office, there has been hope that Israel and Palestine might gradually move beyond this dynamic. But the vaccine debacle is a reminder that the problems are deeper than any one leader—and extend beyond politics.

So where did the “expired” vaccines go?

The June batch went to Israeli teenagers, after Israeli health authorities determined that the country’s unvaccinated youth were at risk from the Delta variant. Notably, Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett filmed a personal appeal to the country’s kids, in which he explicitly explained that the doses were soon to expire, and needed to be used right away.

The July batch, as noted above, went to South Korea. The remaining doses, which reportedly expire in August, are still available. This means there is still a chance to get them to Palestinians in need should the Palestinian Authority—currently wracked by its own scandals—decide to reengage on the subject.

But that political failure is unlikely to be rectified anytime soon due to the failures of two other entities that might have pressured the Palestinian Authority to change course: the media and the human rights community.

In June, rather than rebuke the Palestinian Authority for caving to extremists, several prominent NGOs ranging from Human Rights Watch to Physicians for Human Rights went to bat for the vaccine rejection, credulously echoing the false claim that the doses were essentially expired and unusable. These organizations had the contacts and the expertise to understand that this was not the case, but chose not to employ them, instead reflexively putting forward partisan talking points. Had they instead called out the Palestinian Authority for placing politics ahead of public health, its leaders might have altered course.

Meanwhile, the international media did not do much better. Of all people, journalists should reasonably be expected to get to the bottom of whether Israel or the Palestinian Authority was telling the truth about the vaccines. But instead, too many outlets covered the entire affair in “he-said, she-said” terms, as though the truth was unknowable, rather than something that could be determined by careful reporting. The closing of the New York Times dispatch was emblematic of this approach:

Those who accepted Israel’s official position about the donations said the authority’s refusal to accept the vaccines had dented claims that Israel was to blame for the slow vaccination rate among Palestinians. But those who believed the Palestinian position said Israel had acted in bad faith by making the authority an offer that it had no choice but to refuse.

Had the Palestinian Authority originally agreed to accept the vaccines with these expiration dates? Could the doses be administered in time? Or was Israel’s leftist health minister, whose party includes an Arab minister, involved in a sinister scheme to foist unviable vaccines on the Palestinian population? If only there were some journalists around to find out.

Instead, because the international media and activist community largely punted on these questions, the Palestinian Authority was able to evade scrutiny for its decision, and has not renegotiated a new arrangement.

Even now, there is still time for the relevant actors to do the right thing and find a way to get the remaining Israeli doses to the Palestinian population. But that would require many people to admit their previous mistakes and put helping people ahead of partisan posturing, which in the Israeli-Palestinian context is, sadly, never a good bet.

In the meantime, as long as extremists have veto power over even the most uncontroversial cooperative policies, it will be very hard to make any serious progress on the Israeli-Palestinian impasse. Changing these dynamics—in both Israel and Palestine—must be the top task for political leaders who seek something better.

Yair Rosenberg is a senior writer at Tablet. Subscribe to his newsletter, listen to his music, and follow him on Twitter and Facebook.